Grief On The Page

August 3, 2023

Grief on the Page

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Examining the theme of “Death & Mourning,” Dr. Catherine Walsh shares this story from HMML's Art & Photographs.

How do you represent grief?

For Marc Chagall (1887–1985), the Russian-born Jewish artist who spent most of his active years in France, the topic of grief loomed large in his work. He grappled with the subject several times in a series of etchings and lithographs that he produced over the course of three decades, one of which included a world war.

While Chagall’s work is known for its bold colors and dreamy mingling of narrative elements, viewers often turn to the psychological power of the characters and emotions he conveys. His images make viewers feel. Gaston Bachelard, a French philosopher, has described Chagall’s drawings as “an apotheosis of the face,” and the artist himself as a “skilled psychologist” who “has succeeded in individualizing the prophets.”

Etching the Bible

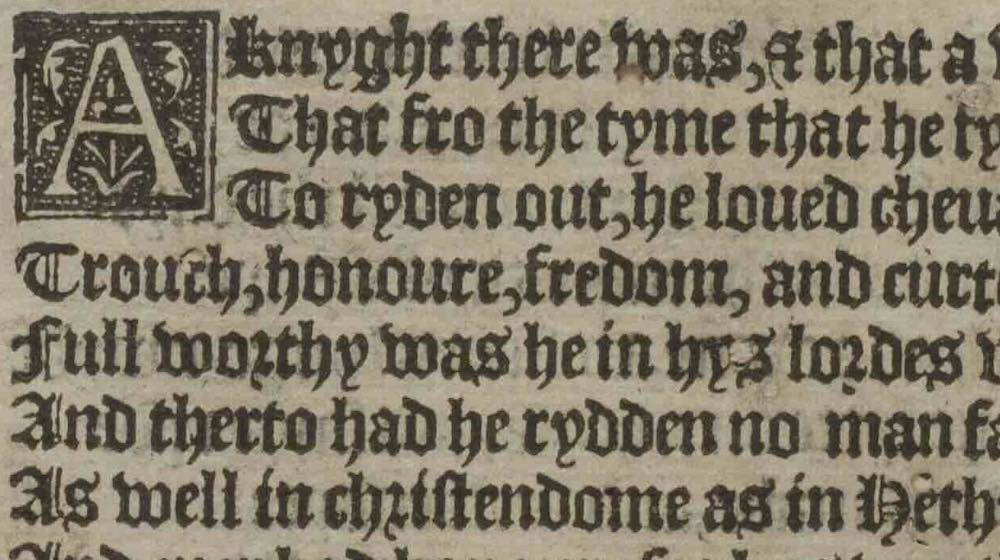

This application of psychology is perhaps most readily apparent in Chagall’s series of 105 etchings called The Bible. Shortly after his return to Paris in 1922, following several years in Russia during World War I and the Russian Revolution, Chagall began working with the art dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939). Vollard was highly respected in the Parisian art world for his collaboration with artists to produce lavishly illustrated books. After seeing paintings by Chagall in the home of a friend, Vollard contacted Chagall and they embarked on a series of three projects: first (from 1924 to 1925), illustrations for Les âmes mortes by Nikolai Gogol; then (from 1926 to 1931) Les Fables by La Fontaine; and finally L'Ancien Testament, or The Bible, begun in 1931.

Chagall’s work for The Bible consumed him for several years. For Chagall, the work was a way to think about the foundational stories of the Jewish religion. He traveled to Palestine with his wife Bella and their 15-year-old daughter Ida from March through June of 1931, which served as research for the series and a chance to meet his friend Meir Dizengoff, who was working to build a Jewish art museum in Tel Aviv.

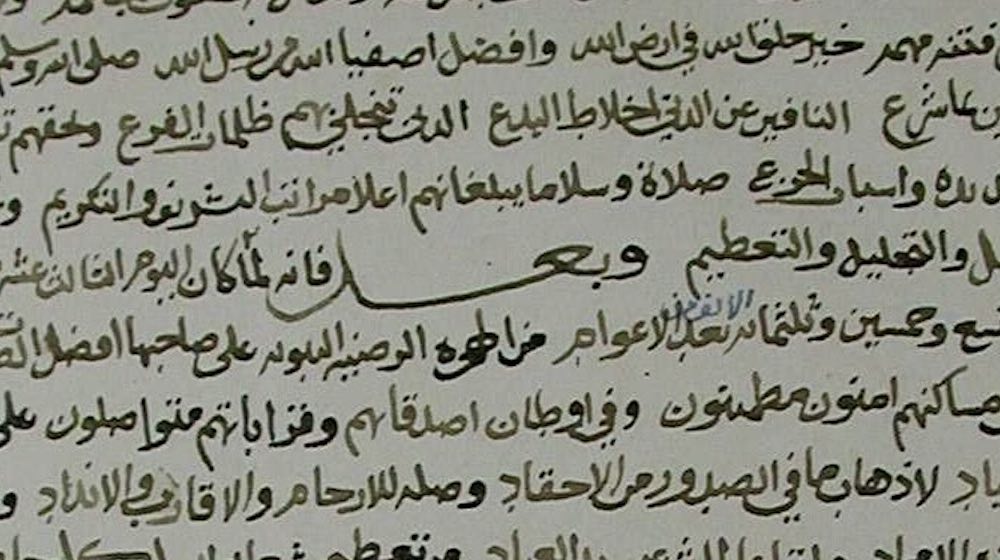

While Chagall had learned Russian and French, Yiddish was the language of his youth and the language he used most frequently in his daily life and writings. He therefore illustrated the Bible following the Yiddish translation by the poet Yehoash (1870–1927), who began publishing his translations in 1926. While Chagall never broadcast this source—he frequently refrained from emphasizing his participation in Yiddish culture—he did mention it in a letter to his friend in New York, Joseph Opatoshu. In the letter, Chagall described his progress on the series: by 1934, he had produced 40 pages of images, but political developments in France—due to the rise of fascism and totalitarianism in Europe—were limiting his ability to work. Chagall wrote:

“I am now ‘sad’ because the work for the Bible which I began to make for the Christian publisher—Vollard—was stopped because of the crisis. I made 40 pages of engravings for the first volume (as in Yehoash). He printed these pages in 375 copies, and like Dead Souls and LaFontaine’s Fables, he hid it in the ‘cellar’ and that’s it. So now they are looking for a crazy publisher who would continue the Bible...”

The work was first interrupted by social circumstances and worsening economic conditions, then by Vollard’s sudden death in 1939. In 1941, Chagall fled Nazi persecution in France, living in New York until 1946. After he returned to France, retrieving the images and plates for The Bible was one of Chagall’s main concerns, the effort peppering his letters as he tried to work out the legal complications of who owned the plates following Vollard’s death. Ultimately, they were purchased by Tériade, the editor of the art journal Verve.

Finally, the last etchings were printed and the images were published in 1956 in a massive double issue of Verve, along with 16 new color and 12 black-ink lithographs produced by the artist.

Grief Beyond Reason

For Chagall, the Bible presented stories that resonated with the depths of human nature and emotional life. Chagall said:

“Since my early youth, I have been fascinated by the Bible. It has always seemed to me, and it seems to me still, that it is the greatest source of poetry of all time. Since then, I have sought this reflection in life and in art. The Bible is like an echo of nature, and this secret I have tried to transmit.”

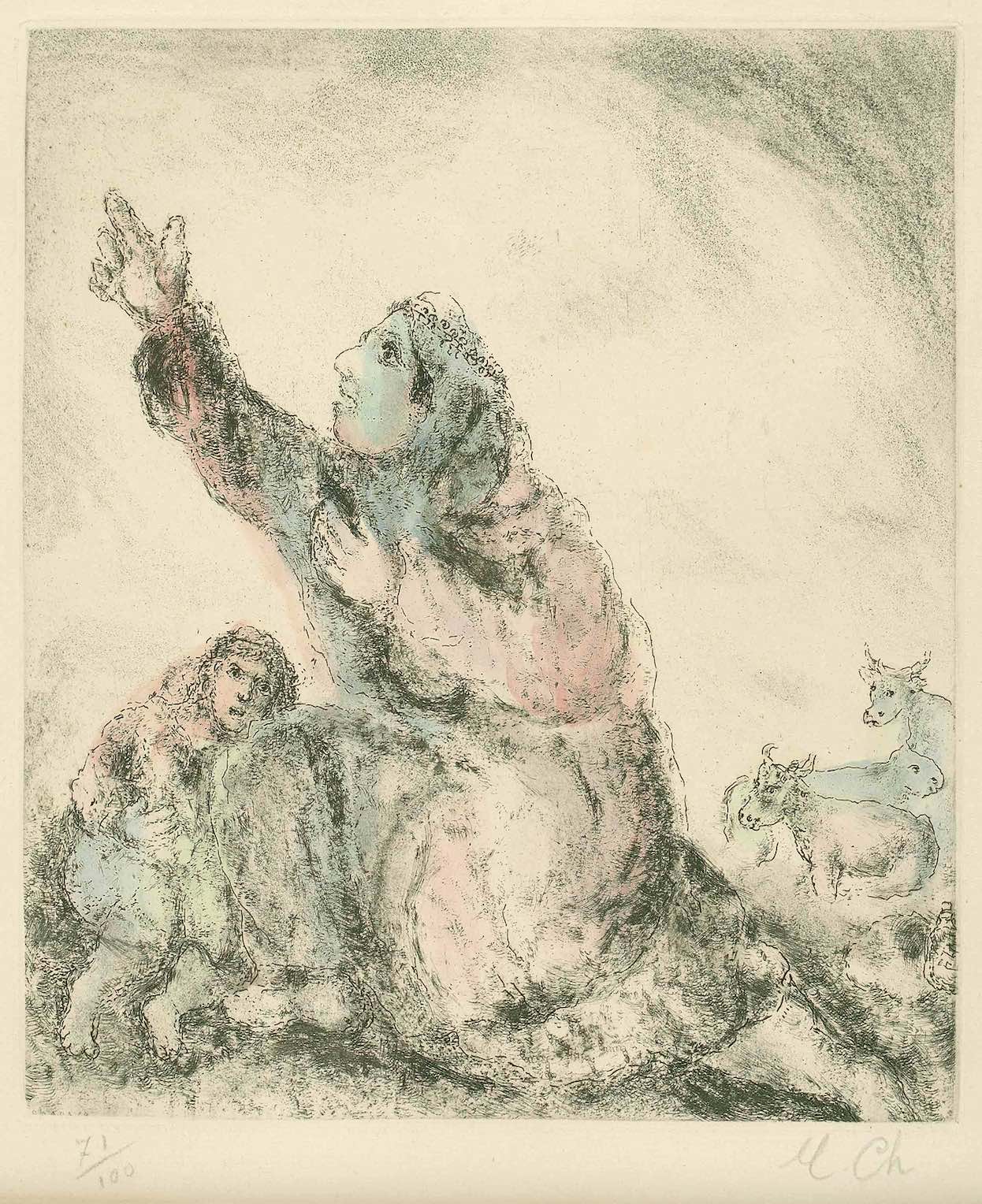

Chagall’s etchings for this series focus strongly on major biblical characters—Abraham, Moses, David—caught in pivotal, emotional moments within their story. Death twines in and about these texts but, for the most part, Chagall avoids the epic death scene so common in Western art. Instead, he returns to the topic of grief: the consequences of death for the living.

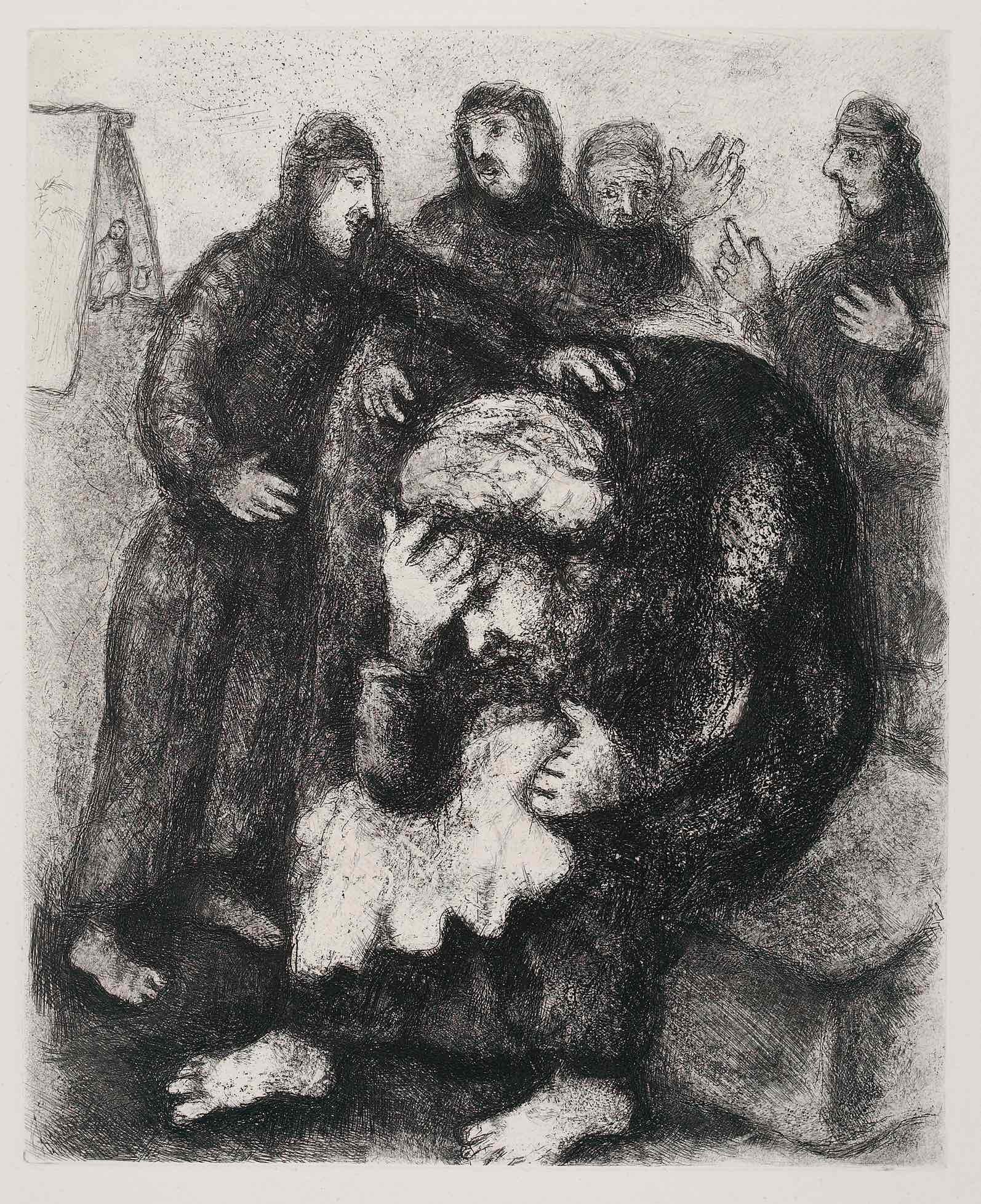

In Jacob Weeping for Joseph, a father’s silent mourning overwhelms the picture. Jacob sits; back hunched, head bowed, and hand covering his forehead. He curls in on himself protectively, his face and hands a frame for the source of his grief. The story is well known: Joseph’s brothers have lied to their father to cover their betrayal, claiming a death that did not occur. Yet, this does not diminish the emotion at the heart of Chagall’s rendering.

The pose and topic echo that of another etching, Abraham Weeping for Sarah. Here a husband mourns the death of his beloved wife, Sarah; she lived 127 years, yet he is no less grieved to lose her. His hand obscures his face, refusing to display the emotions limned there, yet nevertheless drawing the viewer’s attention. (See also the hand-colored etching in the collection of the Jewish Museum, Abraham Weeping for Sarah.)

One story of grief appears not once, but twice, in the 1956 edition of Chagall’s The Bible. In an etching (not pictured), King David sits outside the walls of a city, crowned head bowed, hand covering face, as he mourns the death of his son Absalom. Despite his son’s rebellion and betrayal, David was wracked with grief:

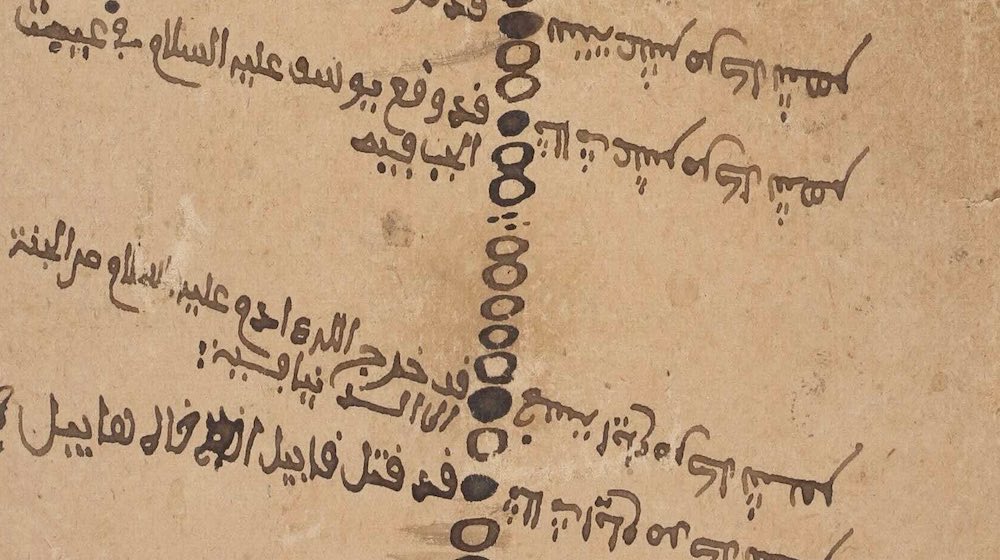

"!מײַן זון אַבֿשָלום, זון מײַנער, אַבֿשָלום מײַן זון! הלװאי װאָלט איך געשטאָרבן אַנשטאָט דיר, אַבֿשָלום מײַן זון, זון מײַנער"(Shmuel Beyz 19:1, Yiddish translation of the Hebrew Bible by the poet Yehoash). Transcription provided by The Yehoyesh Project, contributed by the Hierophant. (CC BY-SA 4.0)

*

“O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!”

(2 Samuel 18:33, translation from the New Revised Standard Version)

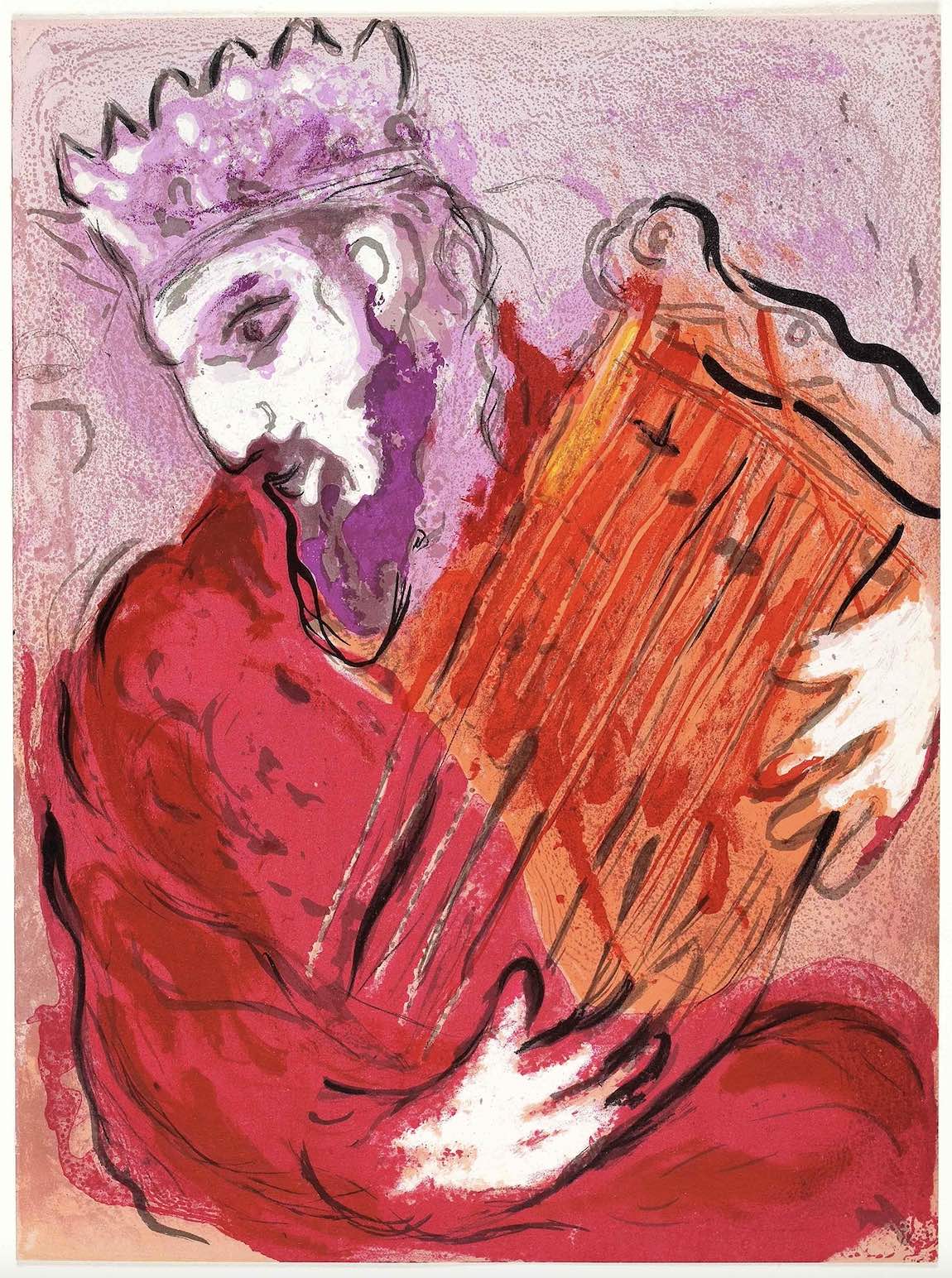

When Chagall returned to The Bible series to produce additional works for the Verve publication, he produced two color lithographs featuring King David. One represents the King playing his harp.

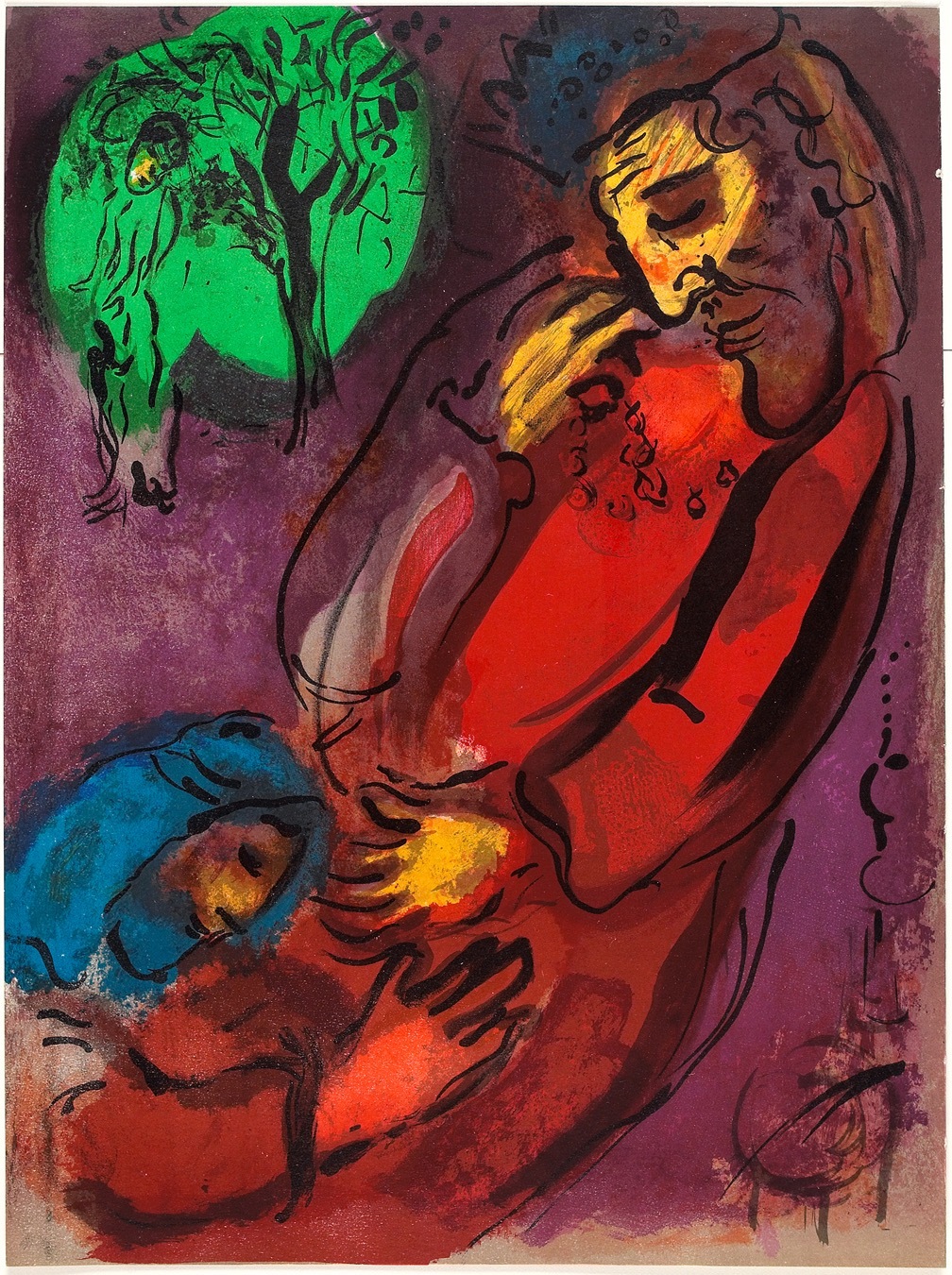

The other returns to the topic of the death of Absalom.

The king mourns. Though his garments and skin are bright reds and yellows, a murky purple surrounds him in darkness and his closed eye is lined, his grief slashing through the saturated yellow like a rectangular bruise.

Why represent this story twice?

One reason is suggested by art historian Jean Bloch Rosensaft, who has argued that Chagall’s Biblical etchings were inescapably impacted by his personal reactions to contemporary events. King David had a special meaning for Chagall. In 1950, Chagall wrote a memorial, “For the Artist Martyrs,” lamenting the persecution of his fellow Jewish artists during the Holocaust.

“Did I know them? Did I go to their studio? Did I contemplate their art from close or from far? And now, I leave myself, my years and go towards their unknown graves. They call me. They pull me with them into their graves, me the innocent one. Me, the guilty one. They ask me: where were you? I ran away...Suddenly, he descends towards me, out of my paintings, the King David I have painted with his harp in his hand. He wants to help me cry, he wants to play the strophes of the Psalms.”

Further Reading:

Benjamin Harshav, Marc Chagall and His Times: A Documentary Narrative (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004).

Jean Bloch Rosensaft, Chagall and the Bible (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1987).

Jean Wahl, Illustrations for the Bible by Marc Chagall (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1956).