Getting It In Writing: Knowledge Preserved And Passed On In Handwritten Catalogs

Getting it in Writing: Knowledge Preserved and Passed on in Handwritten Catalogs

On a recent chilly October morning, I reached for one of HMML’s copies of Paul Oskar Kristeller’s Latin Manuscript Books Before 1600: A List of the Printed Catalogues and Unpublished Inventories of Extant Collections (1960). This book might be called a catalog of catalogs, in which Kristeller identifies bibliographic resources to study manuscript collections across Europe and North America. Upon opening the volume, I found an undated note stuck inside: “Father Aelred, Thank you! Oliver, OSB.”

Sixty years ago, Father Oliver Kapsner was on the road, traveling Austria, Switzerland, and Italy in an attempt to get support for a fledgling project by Saint John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota, to microfilm medieval manuscripts at Benedictine monasteries. Kristeller’s catalog was one of the very few published resources on these libraries, and I believe Fr. Oliver used it during his preparations to find monasteries in Europe that would allow HMML to photograph their manuscripts.

When HMML’s work finally began at the Austrian Abbey of Kremsmünster in April 1965, Fr. Oliver relied heavily on local handwritten catalogs and inventories to get a sense of what he was working with. At Kremsmünster, only 10 medieval manuscripts (of more than 430 in the collection) had been described in a printed catalog. The remainder appeared in a handwritten excerpt copied from an older catalog by two monks between 1903 and 1913.

Fortunately, Fr. Oliver was fluent in both German and Latin, so he could read the excerpt. Over the next six years, he spent hundreds of hours typing any information he could decipher onto index cards; these cards were then microfilmed with their corresponding manuscript to identify its contents.

Fast-forward six decades. HMML’s photographic record of manuscript culture is now so vast that we must provide a catalog of highly accurate descriptions and textual identifications of each manuscript we preserve. If we do not, scholars would not be able to access the digital or microfilm copies. Any search would return “zero results.”

Handwritten catalogs remain a vital resource for the identification of many manuscripts that HMML has photographed—even in large, major collections. Modern printed and online catalogs can provide a wealth of information, but these address only some of the manuscripts in HMML’s care. Fortunately, HMML has always photographed any handwritten catalogs that accompany manuscripts. Many of these photographs of catalogs were subsequently printed and bound for the reference collection at HMML, so that catalogers and scholars could consult them.

Over the past few years, a team at HMML has been updating the online catalog that powers HMML Reading Room, enhancing records for more than 80,000 manuscripts preserved in HMML’s microfilm era (1965–2002). During this work, handwritten catalogs continue to provide insights. While some may be merely brief inventories of a library’s collections, others provide extensive information about the manuscripts’ authors, scribes, titles, dates, and provenance.

The best handwritten catalogs include vital information for identifying the text, such as the incipits (first line of text) and explicits (last line of text). These are especially useful for HMML’s work because many medieval texts are misidentified or misattributed in the manuscripts themselves. With the help of an incipit, HMML staff can often correctly identify a text that was, for example, falsely attributed centuries before to Bernard of Clairvaux, Augustine of Hippo, or others. These contributions to the current knowledge of surviving texts provide a more accurate reference for scholars around the world.

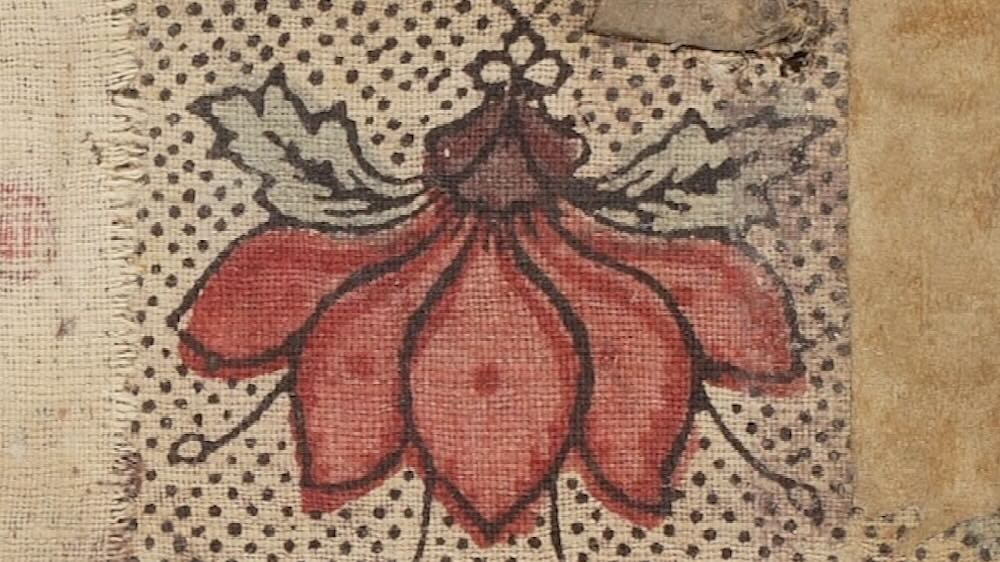

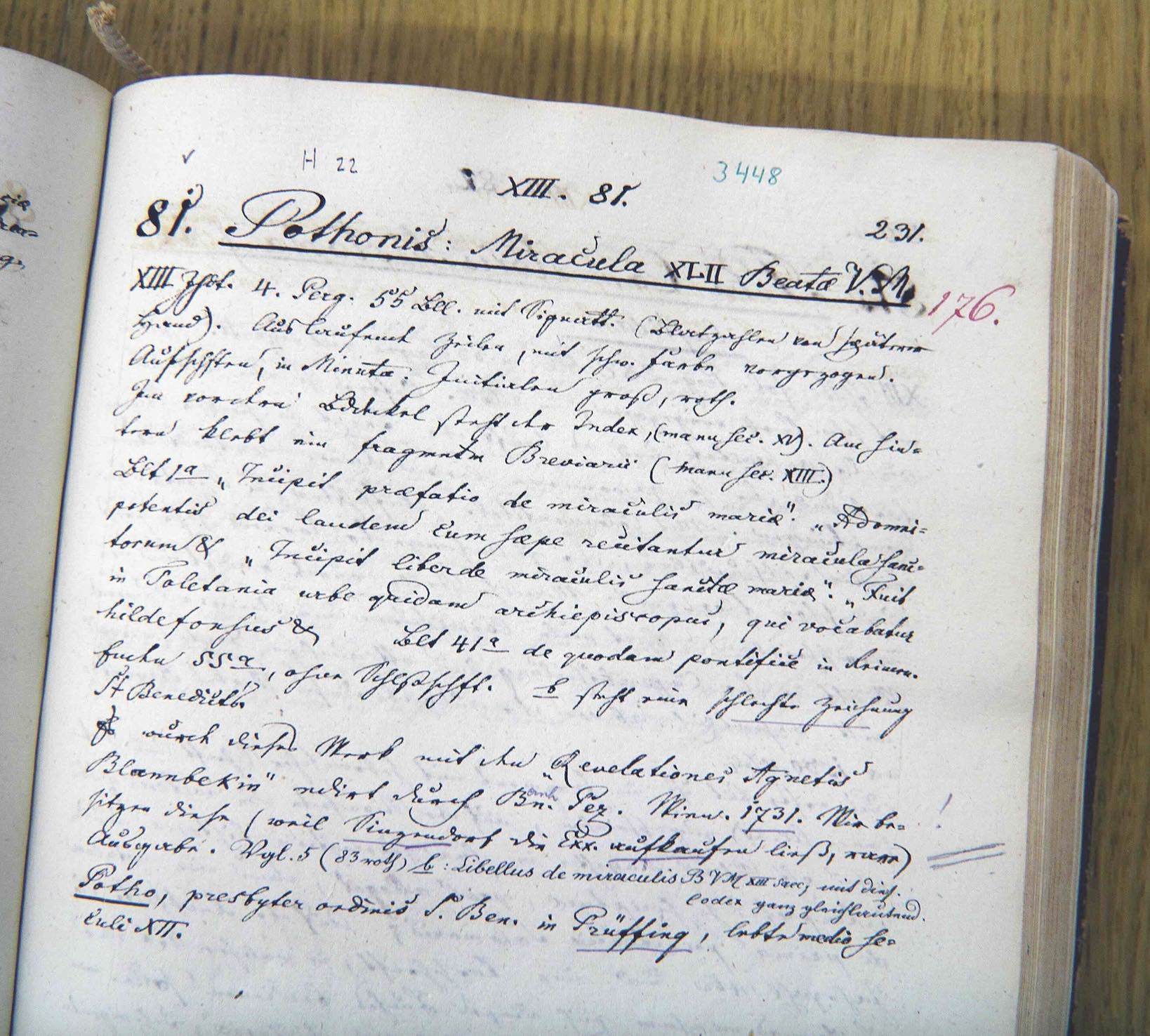

One example of the usefulness of the handwritten record comes to us from the Abbey of Göttweig in Lower Austria.

A manuscript in their library—codex 176 (HMML microfilm 3448)—contains a text on the miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The text was formerly misattributed to Potho of Prüfening, a 12th-century Benedictine monk. One of Göttweig’s handwritten catalogs both contains this error and helps correct it by providing much more information, including a physical description of the object itself, its location in the library, the contents of the manuscript, and an incipit. Today, these insights can be found online in HMML Reading Room.

Each catalog record is a work in progress, building on the knowledge of librarians that came before us and contemporaries that work alongside us. HMML’s record for codex 176 benefited from a photograph made in the 1960s of a catalog written in the 1840s, as well as recent data on the Austrian Academy of Sciences website (manuscripta.at), which aggregates cataloging and digital images for all manuscripts located in Austria.

One more small, intriguing, detail of the Göttweig catalog is worth mentioning. Written in green at the top of the page for codex 176, “3448” tells us where to find the library’s copy of the microfilm that HMML made at Göttweig back in 1966. Thus, this local, handwritten catalog has enriched HMML’s description of the manuscript, while it has in return been enriched by HMML’s work!

A version of this story originally appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of HMML Magazine.