Poetry And Agriculture, A Fragmentary Scrapbook

Poetry and Agriculture, a Fragmentary Scrapbook

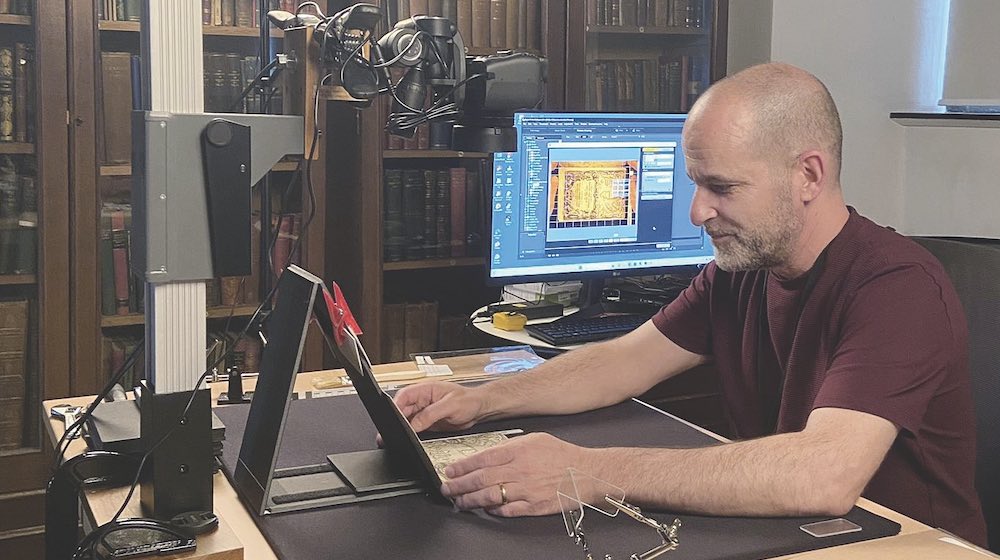

January 19, 2023This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Special Collections, Dr. Catherine Walsh shares this story about Fragments.

Manuscripts are known for their idiosyncratic nature: each volume unique in its presentation, contents, and handwriting. In contrast, printed books are often considered with an assumption of similarity, particularly those made in the 19th century and later, as each edition of a book is run off in many identically printed copies and bindings. Printed books, however, can still offer unique glimpses into the history of their owners.

In HMML’s Special Collections there is an unassuming, small volume, about 16 cm. by 24 cm., only 2.8 cm. thick, with “Centennial Edition” printed on the spine. At first glance, the book seems no different from other printed works from the late 19th century, but upon opening the cover and flipping through the first few pages, the reader is in for a surprise.

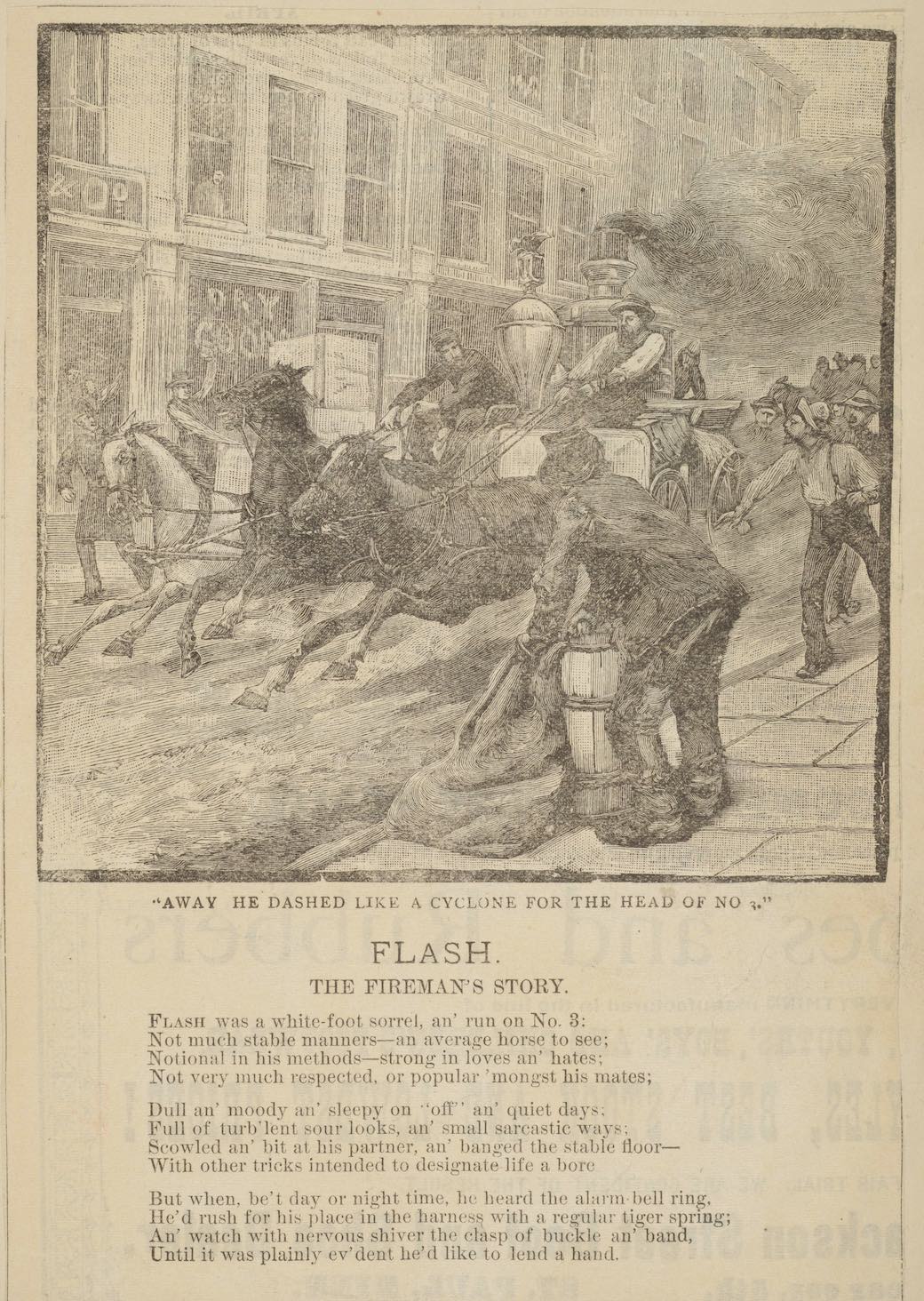

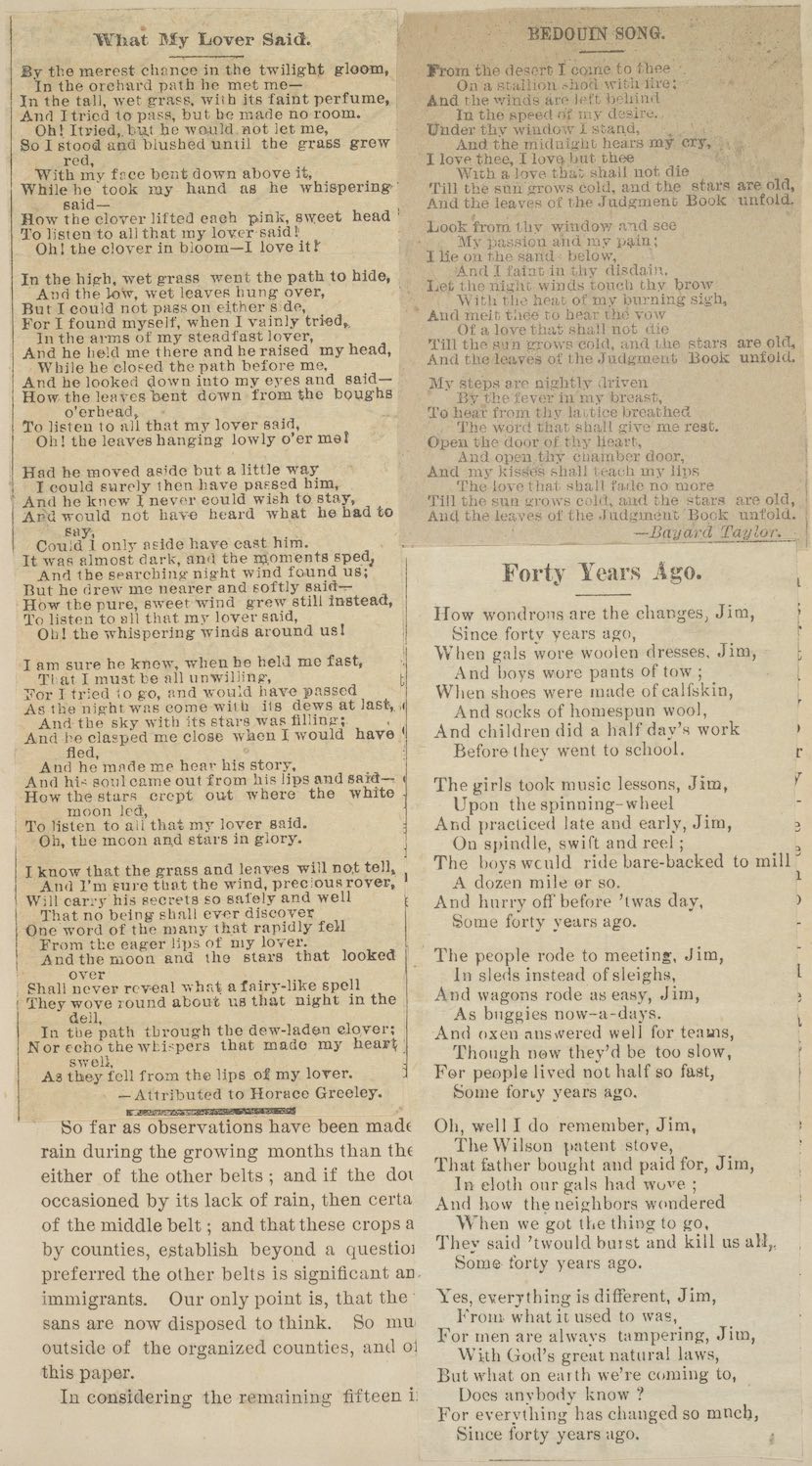

What does one find? Not a well-defined title page, clearly identifying the book for the reader, but rather a full-page pasted clipping of a poem, “Flash: The Fireman’s Story,” complete with an engraving of a smoking fire engine, pulled by racing horses and excitingly captioned, “Away he dashed like a cyclone for the head of no. 3.” This popular text is identifiable as a poem by William McKendree Carleton, published in the October 1882 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

The first 60 pages of the book are similarly treated. News clippings, some short and some long, have been pasted onto the book’s pages. Some cover the text of the original book completely, while others leave elements peeking through, so that short poems alternate with glimpses of the printed book—views of partial county maps, lists of the principal streams or railroad connections of a locality, and charts about swine and sheep increases. After another 80 pages of the original text, another section of scrapbooking begins on page 140, extending until page 152.

The clippings share several similar themes. Almost all are short poems or songs with exciting stories or sentimental, emotional resonance. Some focus on the Bible or religious topics, written by ministers. Others tell love stories or reflect on growing old, solitude, discipline, or grief. The names of famous 19th-century authors—like Horace Greeley and John Greenleaf Whittier—share space with lesser-known poets, many of them women: Jean Ingelow, Harriet Francene Crocker, Danske Dandridge, Alice Cary, Mrs. M. E. Sangster, and Lillian Grey, among others. Poems are often reprinted with a source citation: “…in the Atlantic Monthly,” or “in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle,” etc.

Viewing this object is a process of discovery, showcasing how the fragments of a life edge their way out of (or into) the historical record.

The Original Text

The book’s title page is either covered or torn out, as is the full title on the binding, so we’re presented with our first mystery to solve: what book was this originally? One clue is found in the identifying text at the top of each page (the book’s “running heads”), and searching in online catalogs provides the answer. The book was printed in 1876 by the Kansas Board of Agriculture: it is the centennial edition of the fourth annual report of the State Board of Agriculture.

This edition of the report contains helpful information for those interested in agricultural topics, including maps, charts, and statistics on population, production, property values, crops, and livestock.

The Owner’s Story

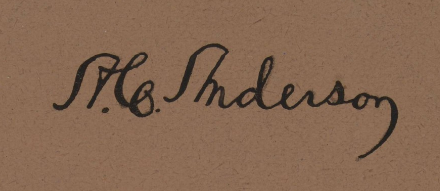

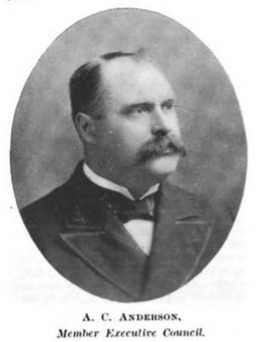

On the front flyleaf, in flourished handwriting, is the signature of the former owner: “A. C. Anderson.”

Another clue waits on the reverse, a partially visible stamp also referencing the owner.

Who was A. C. Anderson?

After some sleuthing through historical archives, a portrait of the owner resolves. His name was Arthur C. Anderson. Born in Bethel, Vermont, Anderson moved with his family to Springfield, Massachusetts, where he attended the Springfield Collegiate Institute and, upon graduation, entered his father’s private banking house, F. W. Anderson & Co. (a name suggested by the stamp on the flyleaf). It was likely during this time, while living in Massachusetts, that Anderson acquired the book, perhaps because of its usefulness in predicting financial matters for agricultural investments. According to the 1880 census, Arthur lived in Springfield with his father (Francis W. Anderson) and mother (Mary W. Anderson), and his two younger sisters (Julia, age 16, and Ada, age 5).

In 1883, Anderson moved with his father to St. Paul, Minnesota, where they both worked at the St. Paul National Bank. He took the book with him. Arthur began as assistant cashier and, over the years, worked his way up through the ranks until he was made president of the bank in 1902.

An up-and-coming professional in St. Paul, Arthur Anderson met a young teacher, Charlotte Ferris, whom he married in 1885. The couple had two sons, Frank (born 1886) and William (born 1888). Charlotte died shortly after the birth of her second son, leaving Arthur a widower in the city.

Collecting Dreams

So, who created the scrapbook?

The author or authors of the scrapbook—the hands that read through local papers, clipped out carefully selected stories, valued them enough to save them, and assembled them into a household volume—left no notes or signatures declaring their identity or purposes.

Most of the poems were popular texts reprinted many times throughout the country during the 1880s, a common practice adopted by local newspapermen seeking to fill columns with material for the average reader. The types of poems in Anderson’s book were often found in sections of publications appealing to female audiences.

For instance, “What My Lover Said” was published anonymously in the “Woman’s World and Work” section of the Dodge County Republican in Kasson, Minnesota, on December 24, 1885, and in at least six other local newspapers between 1880 and 1888. No specific source has been identified for the clippings in HMML’s volume.

The creator could have been Arthur Anderson, of course, but it is more likely that the scrapbooker was a member of his family, reusing his agricultural journal after it became ‘old news’ and therefore much less helpful to a banker. And yet, there are still so many unknowns in this possibility. Did the scrapbooker merely thriftily repurpose an unused book, or was it selected for its creative potential? Was it a transgressive act, tucking away beloved words among the pages of a little-read volume, where one might otherwise not suspect them?

Could it have been Charlotte, a teacher and young wife, who had newly joined the Anderson household in 1885, scrapbooking while she learned her new role? Perhaps it was Julia, Arthur’s younger sister, who had also moved to St. Paul and, in 1885, would have been 21 years old?

We will probably never know, but it helps to remember that fragments are created by someone, and when they are gathered, it is for a purpose. One of the assembled clippings, “A Way to Grow Wise,” offers one way to think about the collection:

“After reading a book or an article, or an item of information from any reliable source, before turning your attention to other things, give two or three minutes’ quiet thought to the subject that has just been presented to your mind…in time the mind, instead of being a lumber-room in which the various contents are thrown together in careless confusion and disorder, will become a store-house where each special class or item of knowledge, neatly labeled, has its own particular place.” (HMML 00631, fol. 57r)

Further Reading:

Minnesota Digital Newspaper Hub, Minnesota Historical Society.

“Portraits and Sketches of Some of the Active Members,” of the American Bankers’ Association, in The Banker’s Magazine, volume 55 (1897), 74.