Where We’re Working: Dayr Anbā Maqār, Egypt

Where We’re Working: Dayr Anbā Maqār, Egypt

Wadi Natrun (meaning, in Arabic, “Natron Valley”) has been a center of religious life since the days of the Pharaohs. In the ancient Egyptian Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, composed around the nineteenth century BCE, this valley is already mentioned as an inhabited area and a source of several luxury products. The region at that time was associated with the worship of Anubis, the jackal-headed god of embalming. During the early centuries of Christianity this valley—then known as Scetis—was the most important center of monastic life in Egypt. Four of the ancient monastic settlements survive today: the Monastery of Saint Bishoi, that of Saint Macarius, the Monastery of the Syrians, and the Monastery of Barāmūs.

Dayr Anbā Maqār

The Monastery of Saint Macarius (in Arabic, Dayr Anbā Maqār) is one of the oldest active Coptic monasteries in Egypt. Founded in the fourth century CE, the monastery was built up in the seventh century by the patriarch Benjamin I and experienced cycles of upheaval, decline, revival, and expansion over the centuries. Roughly a quarter of the patriarchs of the Coptic Orthodox Church were chosen from among the monks of Dayr Anbā Maqār.

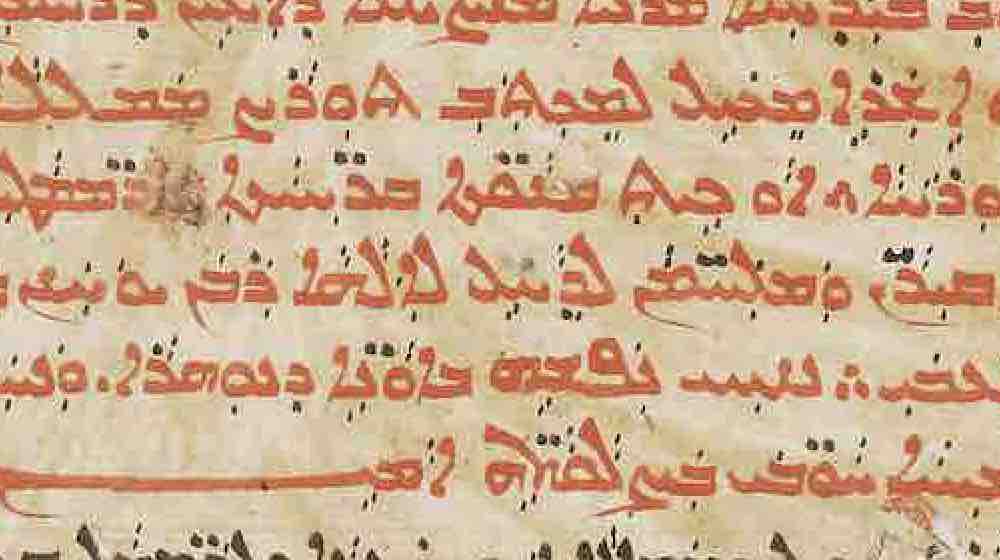

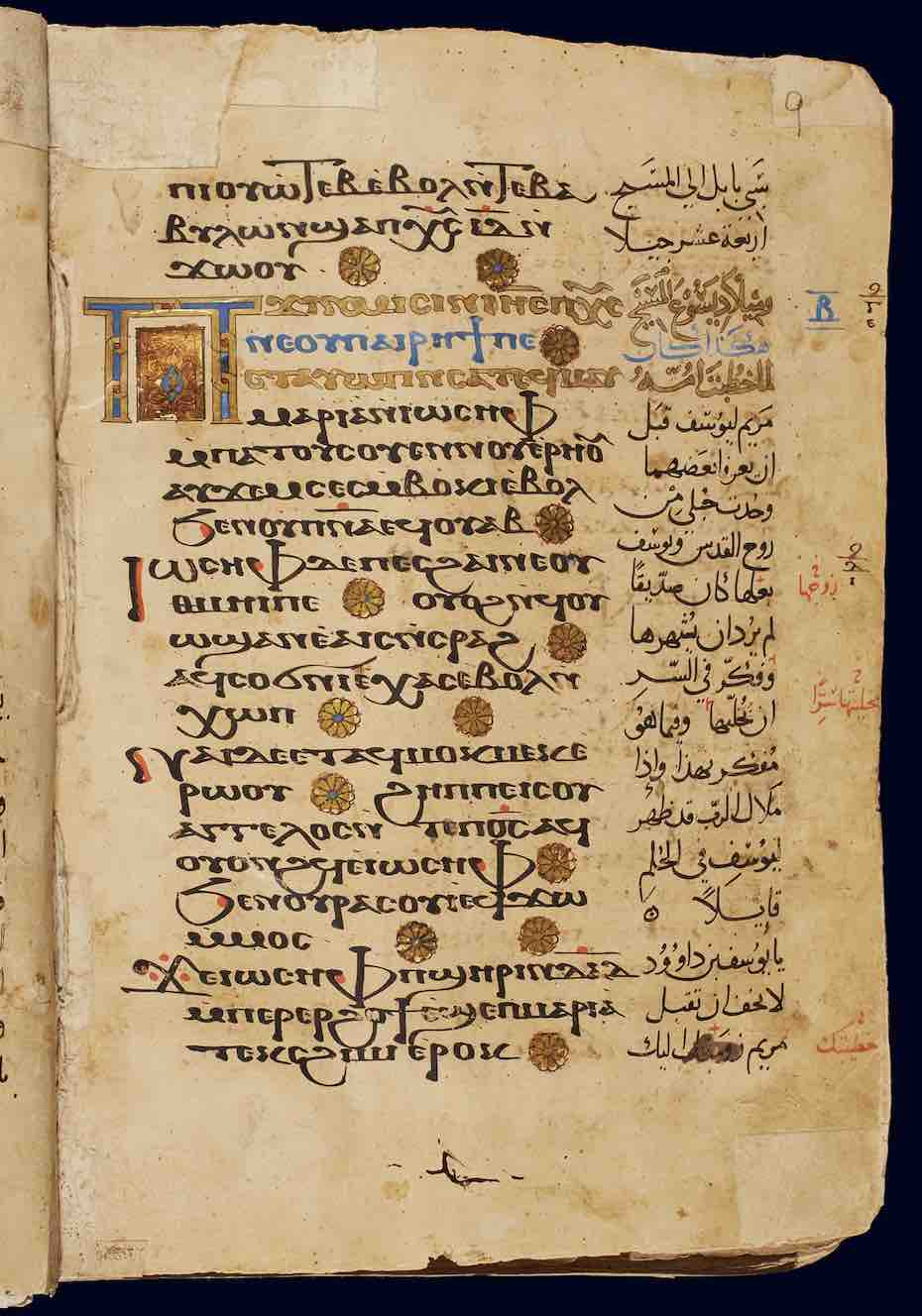

The monastery is known as a source of manuscripts in Bohairic Coptic (the preeminent dialect of Coptic during the Middle Ages). Many of these manuscripts, which once filled an upper room in the southwest corner of the monastery’s keep, now reside in European libraries. However, many fine manuscripts remain at the monastery. The manuscript holdings today number about 550. These include some richly illuminated fourteenth-century Bibles in parallel columns of Coptic and Arabic text. The greater part of the collection consists of Arabic manuscripts dating from the thirteenth to nineteenth centuries, containing Bibles, commentaries, hagiographies, and apocryphal stories.

Digitization and Preservation

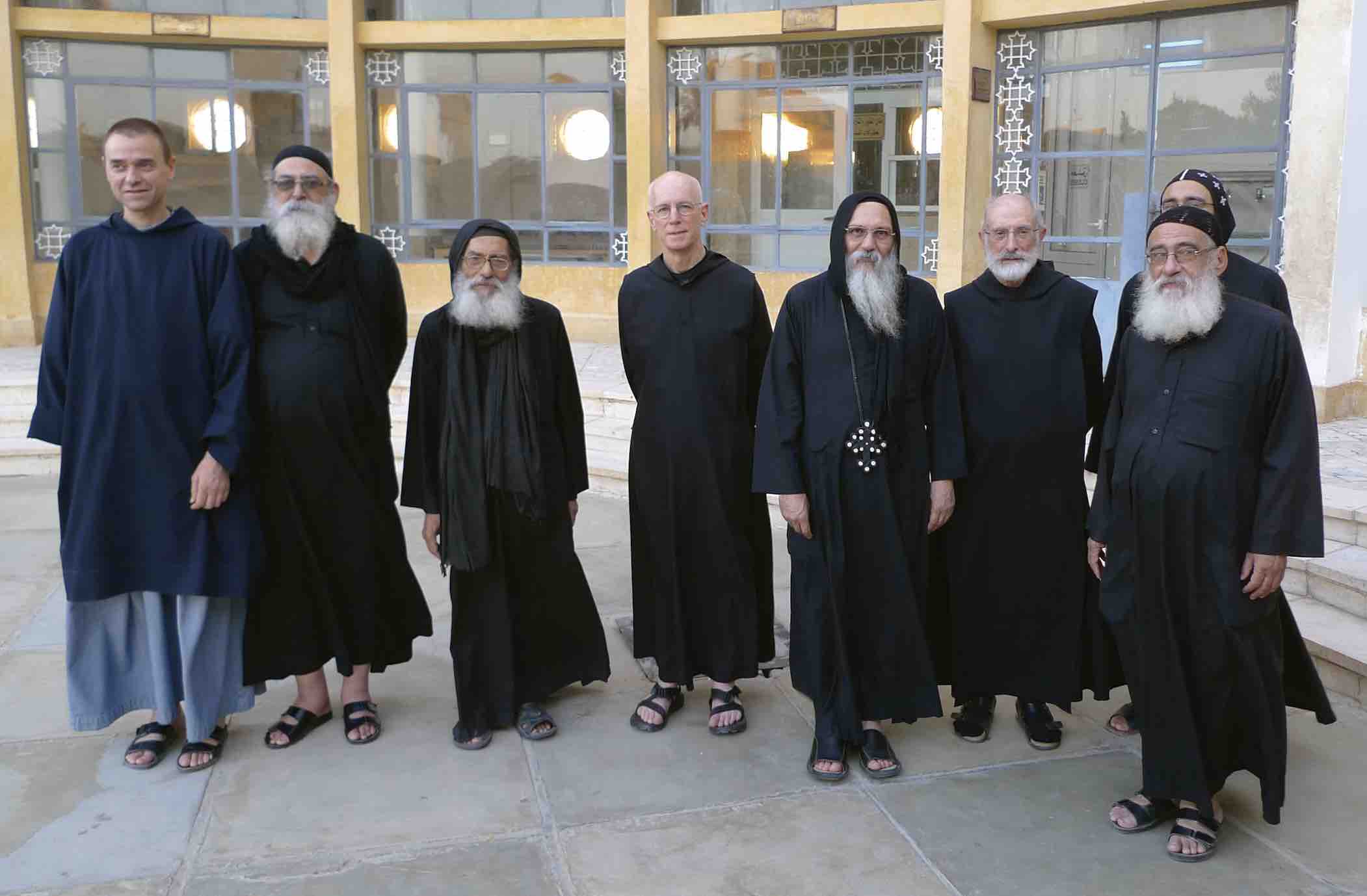

Plans to digitize the collection with the help of HMML began in late 2014, and the project commenced in February 2015. Anba Epiphanius, bishop and abbot of the monastery, and his fellow monk Fr. Wadid were enthusiastic supporters who helped bring this project to fruition. Fr. Bartholomew, another monk at the monastery, directed the digitization. In July 2018, both the monastery and HMML were deeply shocked by the tragic death of Anba Epiphanius. Nevertheless, the close relationship he helped to forge with HMML has remained in place. The project is ongoing, with 71 manuscripts already cataloged and available in HMML Reading Room. The collection is known at HMML, and searchable in Reading Room, by the project code ABMQ.

The digitization of the ABMQ collection has the distinction of being HMML’s first partnership in Egypt. It is also HMML’s first digitized Coptic collection, although scattered manuscripts of Coptic origin are found in other HMML collections. The Coptic language, used today as a liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church, is a modern survival of the ancient Egyptian language of the Pharaohs, although written with an alphabet derived mostly from Greek and incorporating a large amount of Greek vocabulary. Arabic has been the principal language used by Copts from the Middle Ages onward, with Bohairic Coptic retained as a learned language. Thus, Coptic collections like ABMQ include manuscripts written in Arabic as well as in Coptic.

Manuscripts in Conversation

The manuscripts in ABMQ bear witness to a vibrant, cosmopolitan Copto-Arabic culture that flourished from the Middle Ages to the modern era. Interactions between religious communities were frequent. In some manuscripts, the titles of the biblical books reveal that the translation is influenced by the Syriac biblical tradition. In manuscript ABMQ 00006 the scribe offers an interpretation of the Hebrew title of the Book of Judges based on the title’s similarity to the Arabic word for “tribes”; another reader crossed out this interpretation, inserting the correct meaning of the Hebrew term.

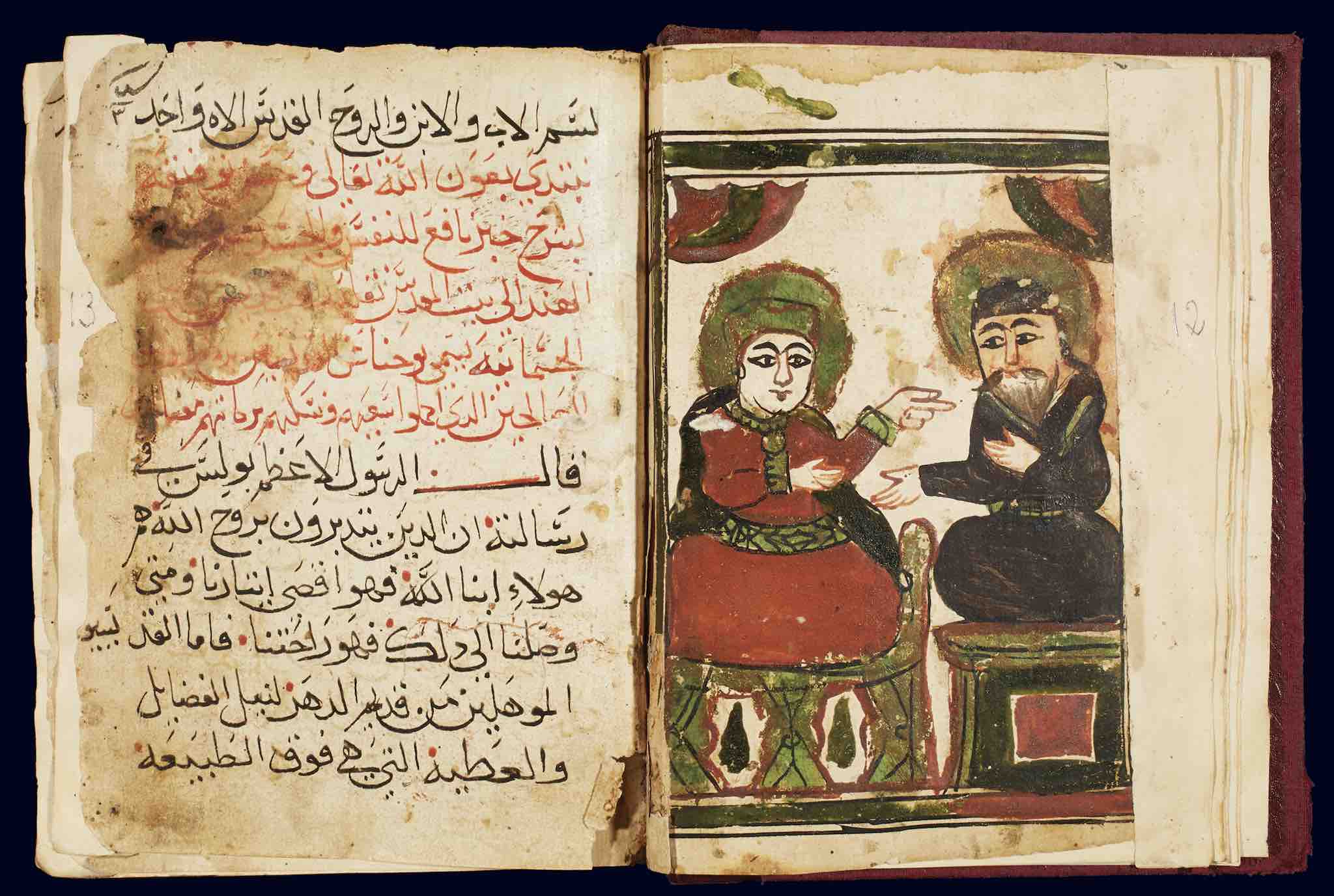

Even the decorative style of the ABMQ manuscripts reveals interaction between communities. The illuminated decoration of the parallel-column Coptic and Arabic Bibles (such as ABMQ 00017, pictured) closely follows that of contemporaneous illuminated copies of the Qur’an. In another example, the eighteenth-century manuscript ABMQ 00399 has a miniature (pictured below) in a style characteristic of Islamic manuscripts of this period, illustrating the story of Barlaam and Joasaph, a hagiographic narrative about a sheltered prince who finds enlightenment through the help of a Christian hermit—a story that circulated across religious boundaries in antiquity, deriving ultimately from the story of the Buddha.

We hope that our work with the ABMQ collection will help illuminate centuries of relationships and will lead to other digitization and preservation projects in Egypt.