Sacred Gingerbread In Southern Germany

Sacred Gingerbread in Southern Germany

Have you ever wondered why gingerbread is a common part of Christmas traditions?

Gingerbread had spiritual significance for different cultures over the millennia, through complex networks that connected diverse peoples and places.

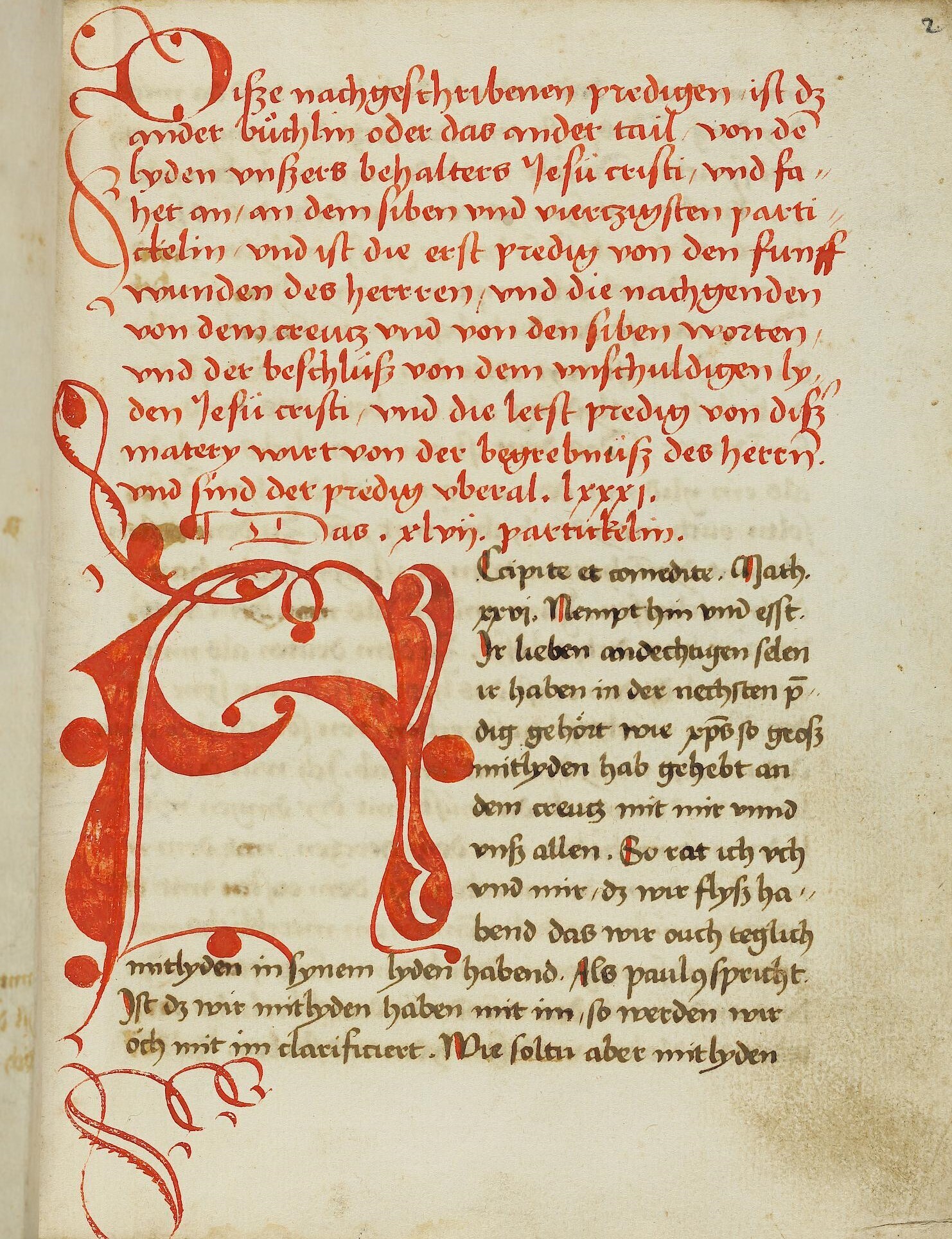

For example, a small, late-medieval tradition of Christian sermons in southern Germany used gingerbread to connect with each stage of Christ’s suffering and death—while each gingerbread piece was distributed to the congregation. The sermons themselves were also compared to these pieces of gingerbread, with every sermon labeled a “particle” (also a term for a piece of the Eucharistic host) and beginning with Christ’s words at the Last Supper (Matthew 26:26), “Take and eat.”

A series of 82 such sermons are preserved in three manuscripts that HMML microfilmed in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, from 1987–1988, in the collection of Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg im Breisgau.

HMML’s microfilm copies (43121, 43122, and 43123) are of the Universitätsbibliothek’s manuscripts 199, 200, and 201. The sermons in these manuscripts were delivered in German in the diocese of Konstanz in 1512, by a preacher whose name is unknown to us.

This is not the only sermon series to feature gingerbread as a metaphor for the passion of Christ. In addition to a few other anonymous sermons that have survived, two authors are known to have compiled gingerbread sermons: contemporaries Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg and Johannes Kreutzer.

Geiler’s 65 sermons were delivered during the seasons of Lent and Easter, and just a few years later the anonymous preacher in Konstanz adapted and expanded them for the entire liturgical year, beginning with New Year’s Day. They introduce the gingerbread as “given to us for a good year,” and play on a regional name for the gingerbread, Lebzelten, parsing it as the “tent of life.” One might imagine that the pieces of gingerbread were distributed during the service, creating a communal experience that engaged the senses of taste, touch, and smell.

In the Middle Ages, gingerbread was consumed during many major holidays and feast days due to its reputation as a delicacy. Gingerbread was also baked in ancient times, used in burial rites and sacred rituals by communities living around the Mediterranean. Over time, gingerbread made its way into what is now France and Germany and eventually into Scandinavia, with recipes emphasizing various spices and fermented honey. The honey and spices were known for their warmth and healing properties, and the bread stored well, making it ideal for the leaner months of the year.

Gingerbread’s ingredients were expensive in northern Europe—the spices were available only through trade and honey required the risky and skilled upkeep of beehives—so gingerbread centers emerged among cities along major trade routes and monasteries that could maintain beehives. In order to keep the dough from sticking, monasteries also baked gingerbread on a base resembling a communion wafer, contributing to its spiritual associations.