Creepy Crawlies And Little Beasts

Creepy Crawlies and Little Beasts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Art & Photographs collection, Katherine Goertz has this story about Animals.

Antwerp seemed, in the 16th century, to be the center of the Western world. The city was at the heart of European business and trade, of book and print publishing, and of scientific thought. It was a cosmopolitan place, where Flemish mixed with dozens of other languages. Ideas, objects, and animals from around the world came through its ports and streets. Although the specters of Spanish rule and religious violence were as much a part of Antwerp as trade ships and bookshops, such concerns deterred few who were more focused on the possibilities of art, science, and philosophy.

The study of the natural world was part of the city’s ethos. A new naturalist movement across Europe positioned the study of plants and animals as the evolution of Renaissance thought—a way of unwinding the mysteries of creation through empirical research and compilation.

Small is Beautiful

Mammals, birds, and sea creatures were popular subjects, famously illustrated in the work of those such as Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) in Switzerland and Pierre Belon (1517–1564) in France. But—by the second half of the century—a group of Antwerp artist-naturalists had turned in a new direction, depicting neither the conventional animals of Europe nor the wonders of the exotic world beyond. These artists went smaller, much smaller. Their artistic world was the continent’s beestjes (little beasts), a category that included insects, arachnids, reptiles, and amphibians.

In Antwerp, Hungarian-born Joris Hoefnagel—the last Early Modern manuscript illuminator in Flanders—turned his attention, career, and legacy toward accurately depicting little creatures. These creepy-crawlies (to use a more modern term) were historically disdained in European science and art, even in the late 16th century. Snakes represented evil, responsible for the fall of man. Insects were associated with corruption and decay. Arachnids symbolized danger, particularly the danger that waited for the foolish and careless. An illustrated epigram in Andrea Alciato’s Emblemata wrote of the base qualities of the common lizard: “…a creature that lurks in holes and hollow tombs…symbols of resentment and wicked deception, known only to jealous wives…”

Hoefnagel broke from these associations in his work. He depicted these little animals as realistically as he could, emphasizing their physical traits and presence in the world rather than repeating the moralizing symbols assigned to them. The motto included in many of his miniatures—natura magistra (“nature his master”)—emphasized the careful detail he applied to his colorful illustrations. His insects, reptiles, and amphibians were rendered in a range of species-specific colors, shapes, and sizes. They were modeled, as the motto instructed, largely from life.

Hoefnagel’s work was later popularly disseminated by his son Jacob. The younger Hoefnagel, who also produced his own naturalist illustrations, was an engraver whose prints were positioned to reach a much larger audience through wider production and circulation.

Engraved Precision

In Antwerp’s publishing district, Flemish engraving was in its golden age. Every year, thousands of prints were created by dozens of designers and engravers and carried by the city’s trade network to audiences across Europe.

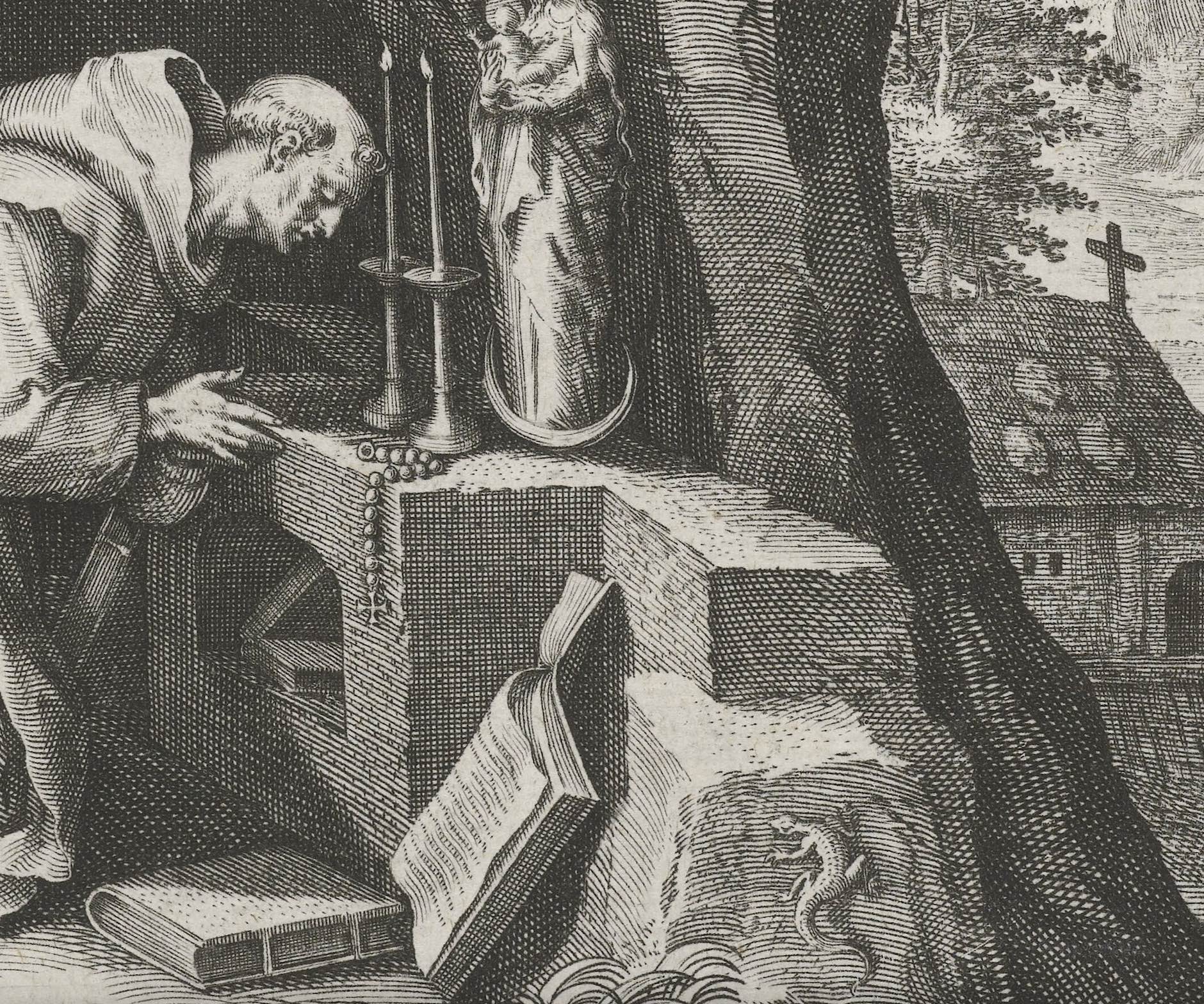

Antwerp’s engravings had a distinct compositional style, one that incorporated such things as recent fashion trends, recognizable Low Countries scenery, and pop culture humor. The animals whose depictions were pioneered by the Hoefnagels and adopted by many other artists fit well into this dense format. In one print, designed by Frans Floris, frogs (as if pulled from a Hoefnagel engraving) swim past an allegorical figure. In another, designed by Maarten de Vos, a porcupine waddles through a biblical scene. A turkey pops up in The Sacrifice of Noah by Symon Novelanus (a few specimens had made it to Europe from the Americas). Sometimes, following Joris Hoefnagel’s example, these animals are precise enough that they are recognizable depictions of a specific species. In an engraving from Maarten de Vos and Johann Sadeler’s series Trophaeum vitae solitariae, a crested Eurasian hoopoe looks at St. Palamonis and St. Pachomius, as if wondering what they are doing in his forest.

Long Lives the Lizard

The depictions of this period were so detailed, it is possible to track the same animal across engravings, tracing how it was used by artists over decades. A certain lizard of the spiny-footed type—the rock dwellers and wall climbers common to Southern Europe—appears all over Antwerpian engravings.

Distinguished by lines of spots, a long whippy tail, and a pointed head, the lizard is easily recognizable. It is seen alongside the rocky approach to Andalusia’s Alhama de Granada in Alhama (1575), an engraving designed by Joris Hoefnagel. And it appears in at least six other works believed to have been created by Alhama’s attributed engraver, Symon Novelanus. In Novelanus’ Shipwreck, the lizard sits in the middle of a road leading away from the scene of a wrecked ship and drowned bodies. And on three different occasions, a lizard hides in Novelanus’ tree roots: climbing on a rock in Expulsion from Paradise, looking up at Hagar in Hagar in the Desert, and watching (mouth open) as brother kills brother in Cain and Abel.

In a series depicting the story of Adam and Eve, designed in 1585 by Crispijn van den Broek, the spiny-footed lizard appears three times, always displaying a rather tranquil persona. In The Creation of Adam, it appears in the lower right foreground corner, placidly looking at the ground. (A snake at the left foreground is not nearly so placid, staring as God breathes life into Adam.) In Adam and Eve in the Garden, the lizard falls farther from the central action, retreating to the mid-ground. Expulsion from Paradise (pictured earlier) brings the lizard back to the foreground. It is, however, still exempt from the central narrative focusing on Adam, Eve, and the snake, who are forced from Paradise by a sword wielding angel. With its back turned to the drama behind it, the lizard calmly focuses on a few engraved lines of grass.

Both habits and habitats are utilized in Flemish depictions of the spiny-footed lizard. The lizard is one of the animals that surrounds an allegorical figure in Timiditas (1592), engraved by Raphael Sadeler after a drawing by Maarten de Vos. The creature was likely chosen for this depiction of the vice of fear due to the characteristic rapidity with which wall and rock lizards dart to safety when startled. Its more quotidian qualities—crawling on rocks and walls—are the focus in a series of works by de Vos and the Sadeler brothers that depict the lives of hermits, the nearly full series of which is in the Arca Artium collection at HMML.

Sometimes, in these engravings, a lizard’s presence contrasts the tumult of human endeavors with nature’s peace. But even this role is not consistent or particularly conclusive. So why is the lizard there?

As it was with the other beestjes of Antwerp’s art world, the spiny-footed lizards had a larger cultural burden to bear. With so many engravings moving around the world, buyers had high expectations. The audience for Antwerp’s engravings expected new imagery in their prints, imagery reflecting intellectual and popular trends and containing interesting sights—like detailed and engaging little animals.

Unlike the exotic turkey or giraffe, lizards would have been familiar to viewers, a little “Easter egg” of everyday life. The artists’ enjoyment in depicting these little creatures is clear in the images themselves. However, the new visual language of the natural world had an even greater meaning. These animals and their ties to the international realm of scientific study reflected how Antwerp and its print consumers wished to see themselves—as cosmopolitan, modern, and engaged with the world of science and intellectual thought. Quite a load on the back of such a little lizard!