Celebrating Shakespeare, Celebrating Friendship

Celebrating Shakespeare, Celebrating Friendship

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From Special Collections, Dr. Audrey Thorstad has this story about Celebrations.

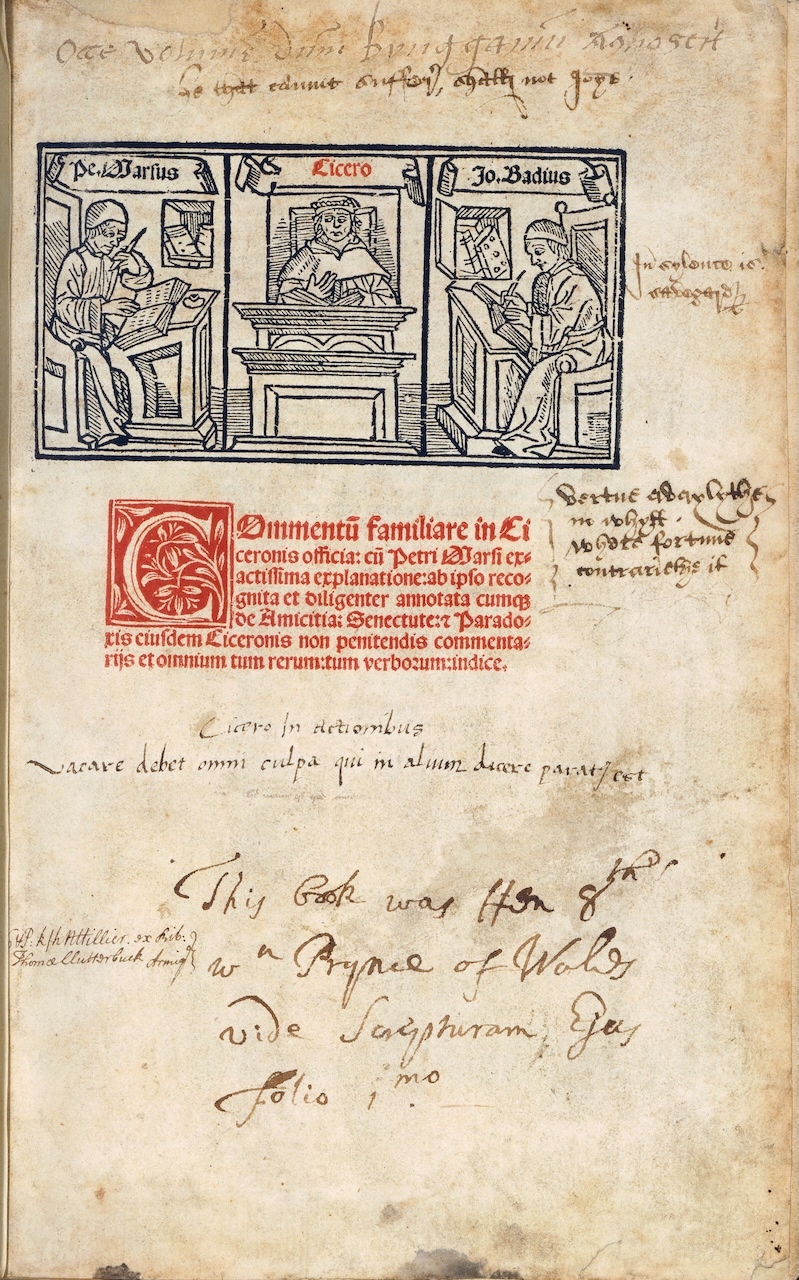

Pick up any modern book today and you will likely find short quotes on the front or rear cover, celebrating the book and praising the author. This style of promotion is by no means new—it comes from a long tradition that accompanied the rise of printing in early modern Europe.

In England, as elsewhere, many 17th-century printed books opened with short praise poems celebrating the author or patron of the work. These poems were usually located in a book’s preface, after the title page and dedication page. An innovation of Renaissance humanists, the poems gained popularity in England during the first half of the 1600s. Praise poems were, in part, works of fluff and flattery, as much as being advertisements to help sell books to the eager public.

Many writers also saw praise poems as opportunities to celebrate sincere friendships and the achievements of other authors. This was especially the case among the small community of actors and playwrights in 17th-century London, where theater was emerging as a popular form of entertainment.

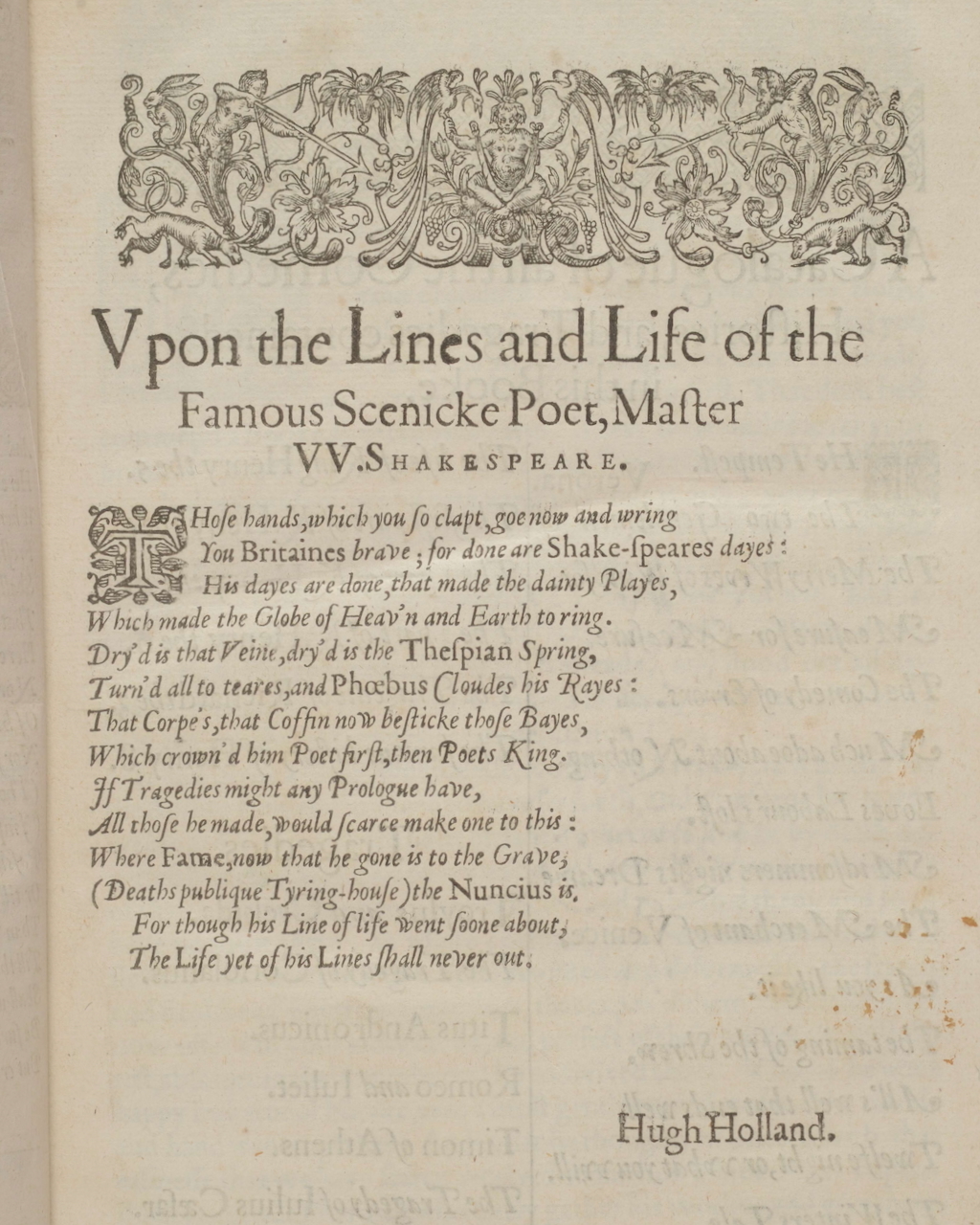

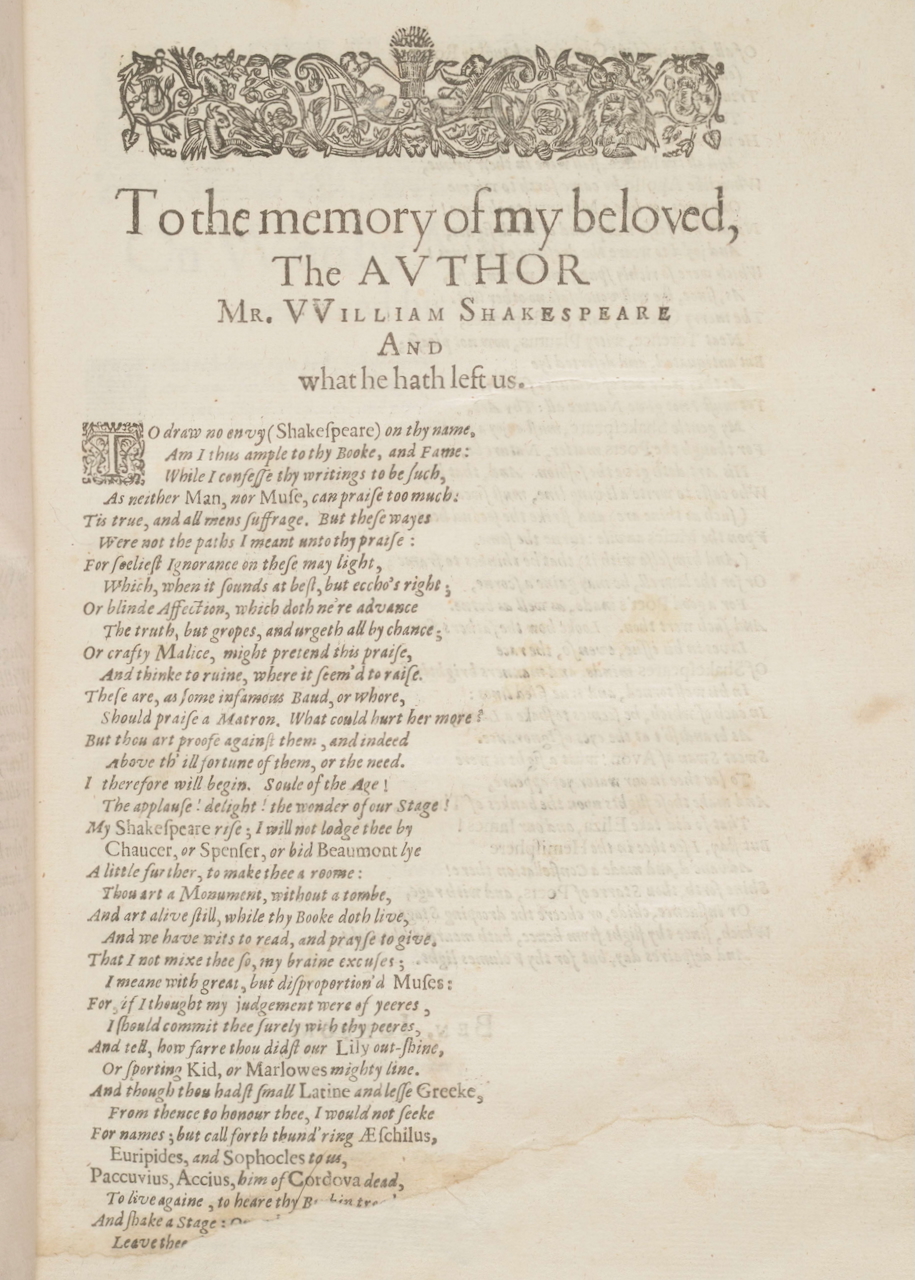

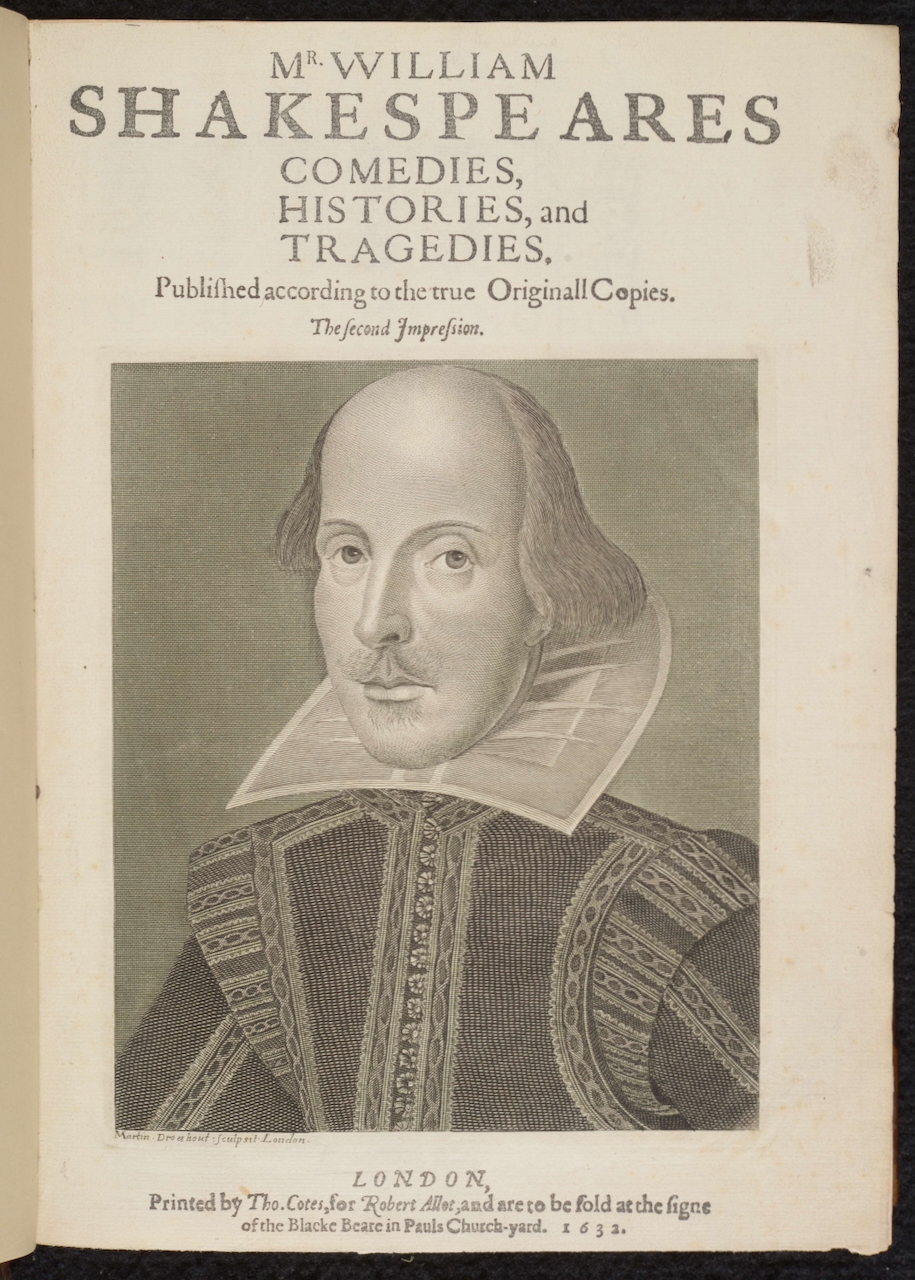

The Second Folio of William Shakespeare's plays, printed posthumously in 1632, contains four praise poems in the preface. The poems were written by fellow poets and playwrights, including John Milton, Ben Jonson, Leonard Digges, and Hugh Holland. The longest poem in the Second Folio is Ben Jonson’s 70-line poem “To the memory of my beloved, the AVTHOR MR. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE: AND what he hath left vs.”

Jonson had a personal relationship with Shakespeare. The two men worked closely together in the same theater company and even acted in each other’s plays. Their deep connection is expressed in the first lines of Jonson’s poem, where he dedicates the verse: “To the memory of my beloved.” The possessive pronoun “my,” referring to Shakespeare, suggests an emotional closeness with his fellow actor and author. Jonson’s devotion appears throughout the poem, often punctuated for effect:

“I therefore will begin. Soul of the age!

The applause, delight, the wonder of our stage!

My Shakespeare, rise!”

—Ben Jonson, “To the memory of my beloved”

This declaration speaks to a form of mourning that was not about tears but rather a celebration of stature and renown. To “rise” is not just to resurrect Shakespeare in memory, but to raise him above all others. Elevating the Bard immortalizes in words the emotional, personal, and intimate friendship between Jonson and Shakespeare. It also, importantly, proclaims Shakespeare as an established author in the English literary canon.

The very form of Jonson’s poem—a public homage to a fellow writer—reveals how early modern men expressed emotional intimacy with other men. Jonson is staking a personal claim—to closeness with and love of “My Shakespeare”—and doing so within the confines of his time.

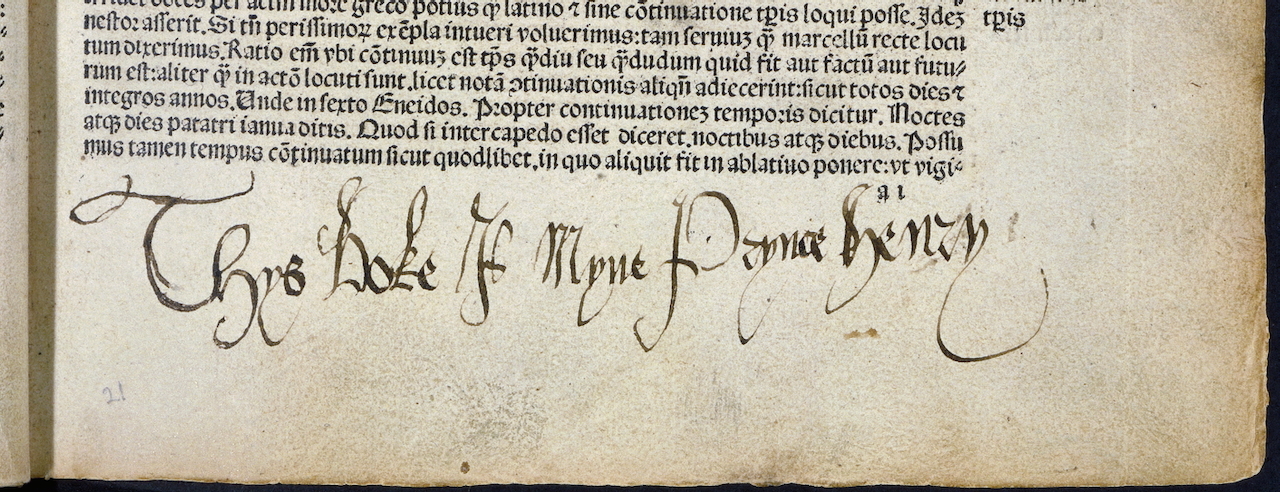

Platonic, but intimate friendships between men of high status were considered a form of amicitia perfecta, or the “perfect friendship,” a concept taken from classical literature. Influenced by earlier sources, the Roman author Cicero described his philosophy of the perfect friendship in his treatise De amicitia (On Friendship) as “one soul in two bodies.”

With the rise of Renaissance humanism, classical authors, such as Cicero, became a staple in Europe’s liberal arts curriculum. Grammar school pupils in the 16th and 17th centuries would translate and study examples of ideal male relationships from classical and Biblical stories, including Damon and Pithias, Orestes and Pylades, Achilles and Patroclus, and David and Jonathon.

According to Cicero and later early-modern writers, the perfect friendship involved deep passions but was grounded in virtues. Men who wished to find the perfect friend also needed to practice restraint and self-control. Jonson follows this model, expressing his love for Shakespeare through the social parameters of the time. He writes of his deep affection, but with modulation:

“I loved the man, and do honour his memory (on this side idolatry) as much as any.”

—Ben Jonson, “To the memory of my beloved”

Jonson’s clear distinction between honoring and idolizing clarifies that he was not falling into hero worship; instead, he maintained control over his admiration. His love for the Bard was tempered and measured. This was an expression of love between men, delivered in a way that was socially acceptable in 17th-century England.

_p_237.png)

Public life in 17th-century England was, predominantly, only open to men, so the figure of the poet was understood through what were thought of as masculine virtues: creative power, public voice, and mastery over language and form. In Jonson’s eyes, Shakespeare embodied the ultimate male artist—not merely inspired by Nature (personified, in the poem, in the feminine) but actively shaping her:

“Nature herself was proud of his designs

[…]

Yet must I not give Nature all: thy art,

My gentle Shakespeare, must enjoy a part.

For though the poet’s matter nature be,

His art doth give the fashion; and, that he

Who casts to write a living line, must sweat,

(Such as thine are) and strike the second heat

Upon the Muses’ anvil; turn the same”

—Ben Jonson, “To the memory of my beloved”

Jonson frames Shakespeare not as a passive vessel of inspiration, but as a master of his art. The poet is a smith at the forge, hammering truth into form. Shakespeare’s fame comes not from swordsmanship but from penmanship’s physicality, where the author “must sweat” to “write a living line.”

The poem is an act of cultural mythmaking, serving cosmological, sociological, and literary functions. “To the memory of my beloved” aligns with cultural norms of masculinity in 17th-century London, where emotions had to be offset with intellectual control, while also allowing Jonson to express grief, love, and celebration for a dear friend. And, in advocating for Shakespeare’s place in the literary canon, Jonson’s own authorship was canonized alongside the Bard’s.