Remembering Good Deeds

Remembering Good Deeds

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From Special Collections, Dr. Catherine Walsh has this story about Celebrations.

Have you ever celebrated a special occasion with a homemade gift? Perhaps you made your own valentine or crafted a card or booklet for a loved one. Would you be surprised to know that you took part in a tradition going back centuries?

In 1883, James D. Reid decided to spend his time on exactly this kind of labor of love…on a grand scale.

Reid was a devout Baptist and member of the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church. The congregation was composed predominantly of prominent New York City businessmen and their families. Since 1870, the church and its members had worked to sponsor a mission church in the Bowery—a neighborhood in Manhattan composed, at that time, largely of immigrants. Although the Bowery church, led by the pastor Reverend Samuel Alman, had seen some success it also suffered upheaval, bouncing repeatedly from location to location over a decade.

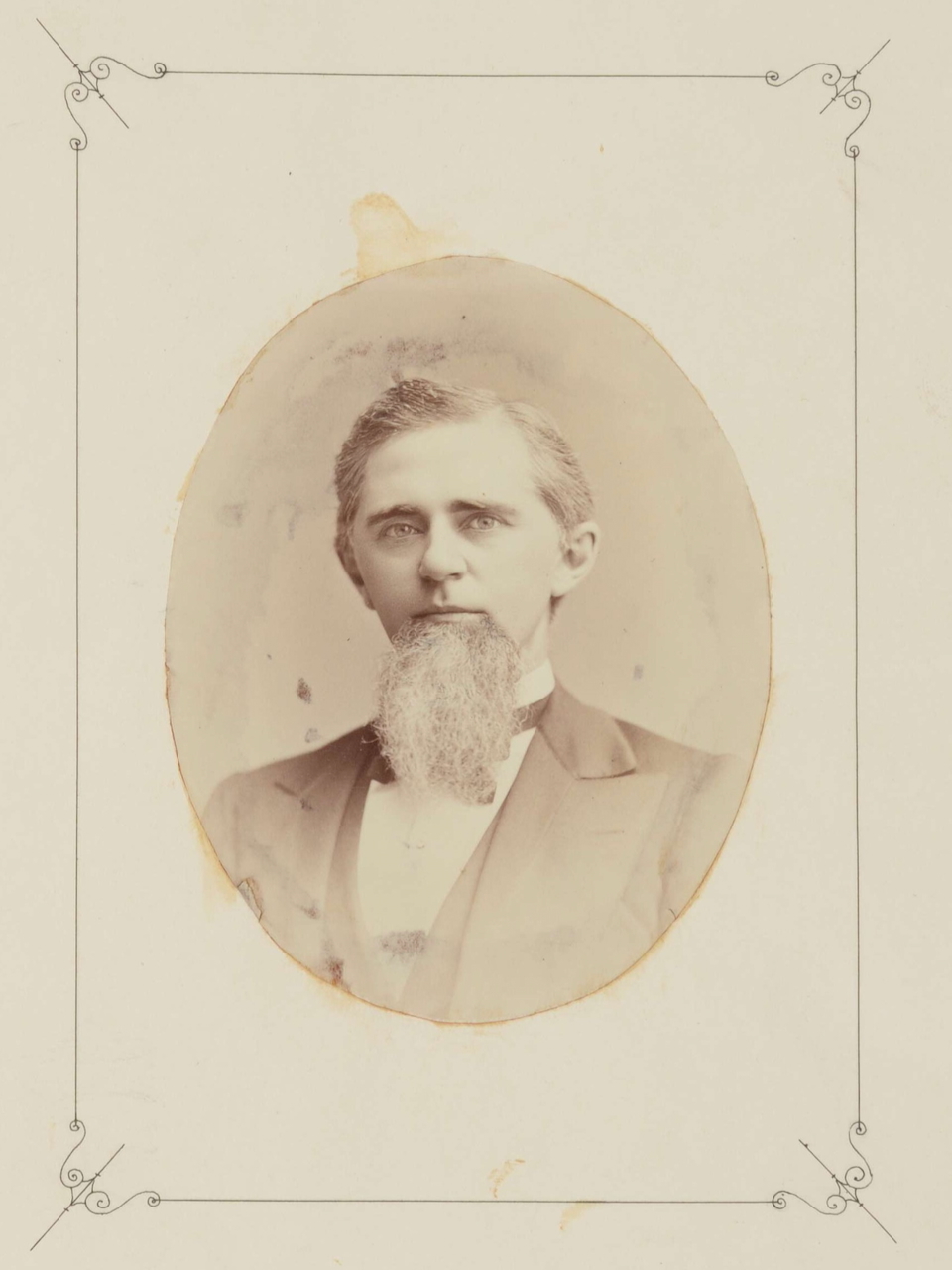

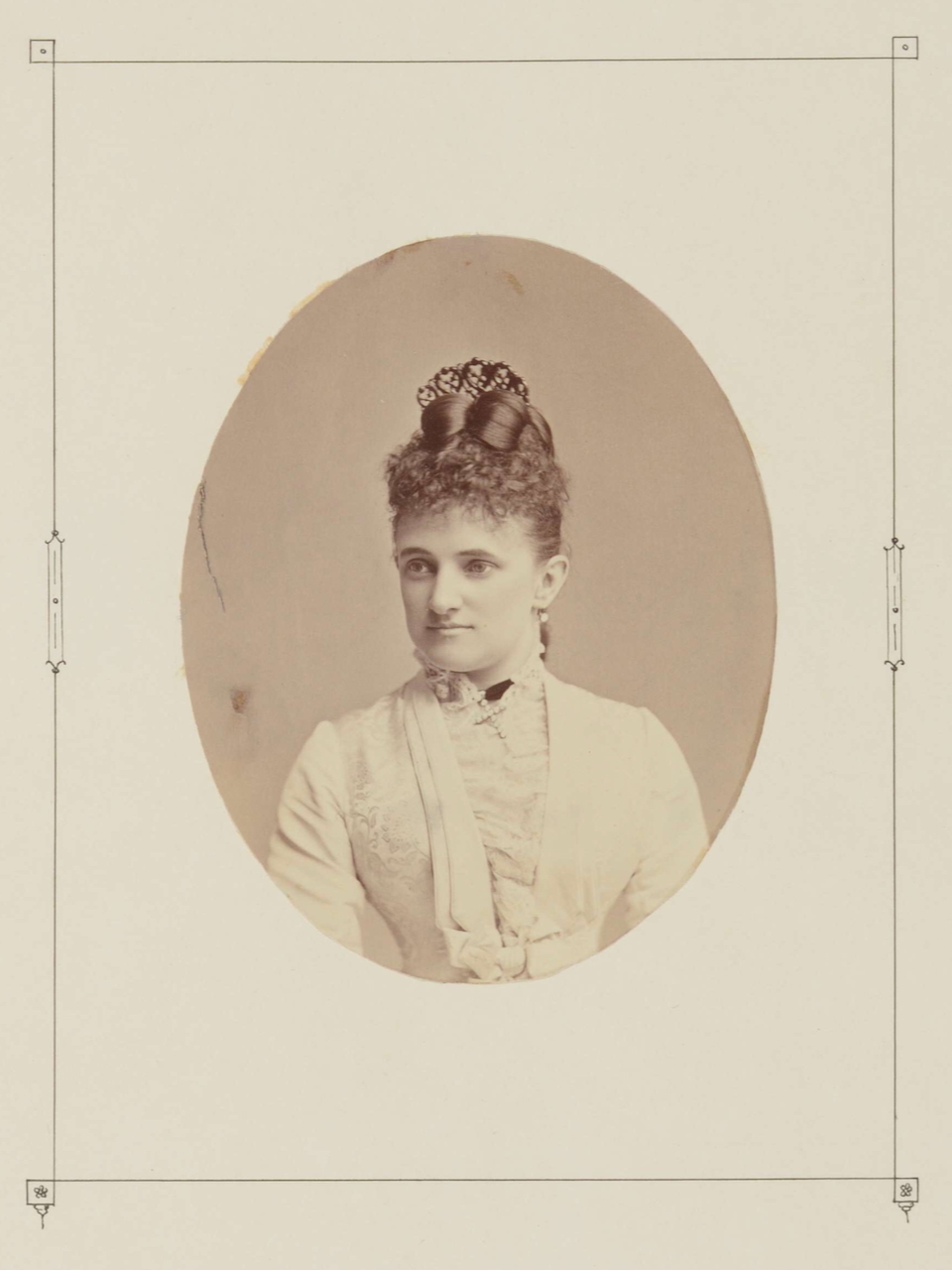

Then, in 1883, a surprise! Jabez A. Bostwick (an American businessman best known for his association with the Standard Oil Trust) and his wife Helen C. Bostwick donated land and a building to solve the problem of dislocation. The new Emmanuel Baptist Church was on Suffolk Street near Grand Street, and this donation was of such monumental importance to the community that a weeklong celebration was held upon its dedication.

Reid attended the celebration on April 15, 1883, which was described in the New York Times the next day: “the pulpit and platform were decorated with flowers, which shed their perfume throughout the church, and a chorus choir of girls led the singing.”

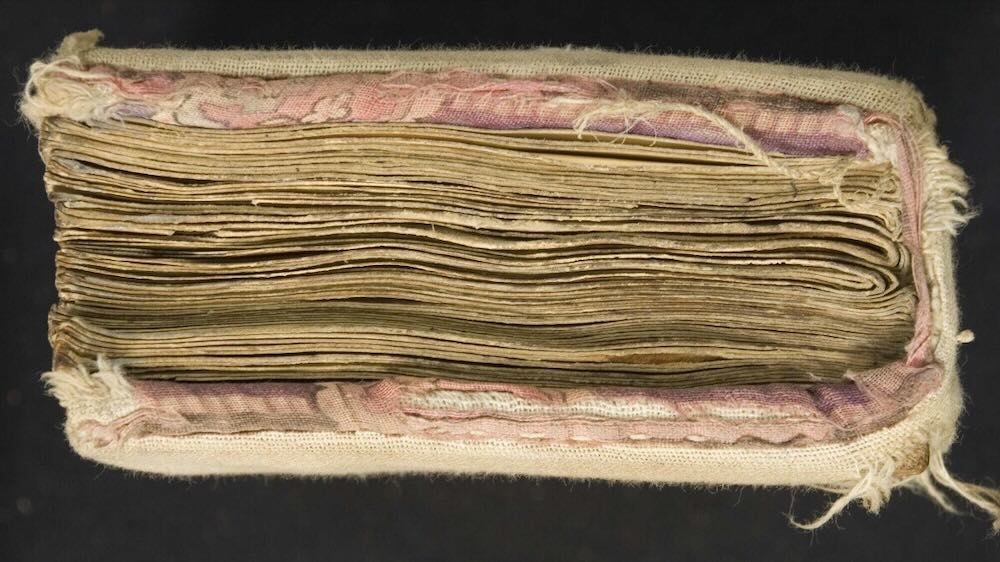

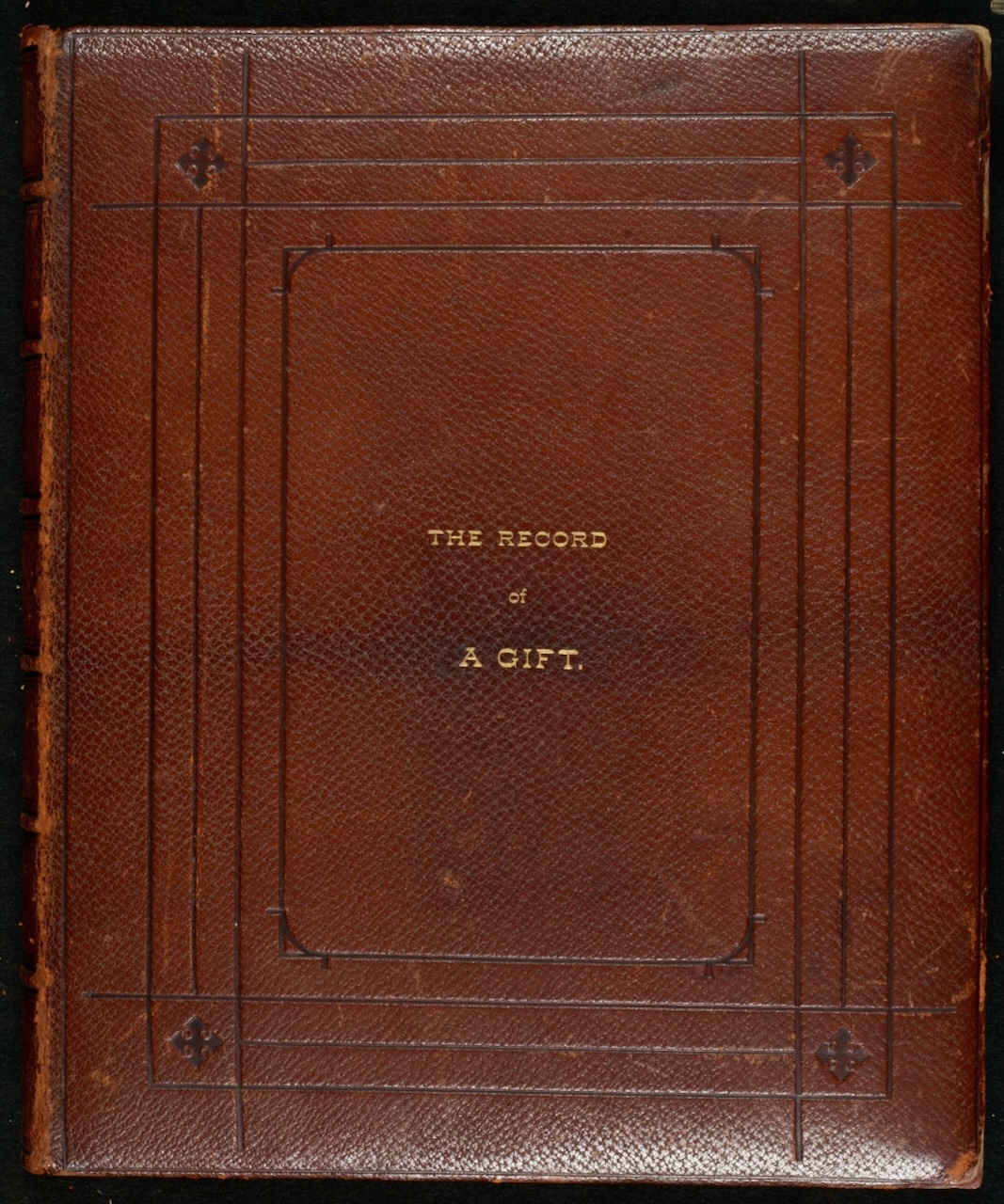

Reid was moved by the festivities—or maybe saw an opportunity for advancement—so he decided not to let the celebration stop there. In an effort that must have taken hundreds of hours, he created a large bound album, labeled in gilt lettering on stamped leather as simply The Record of a Gift.

Inside, the book contains more than 100 folios with writing commemorating the dedication (the handwriting is so meticulous that at first glance it appears printed—it’s not!). In his lyrical preface, Reid announces:

“I have indulged myself, at intervals of leisure, in making this manuscript record of the services of the first day of the week of dedication as a token of my personal esteem for Mr. Bostwick to whom it is my design to present it. I trust that it will be to him a pleasant memorial of a great service done to New York and to the work of human redemption which has enshrined him in many hearts in deep and loving regard.”

And what a record it is!

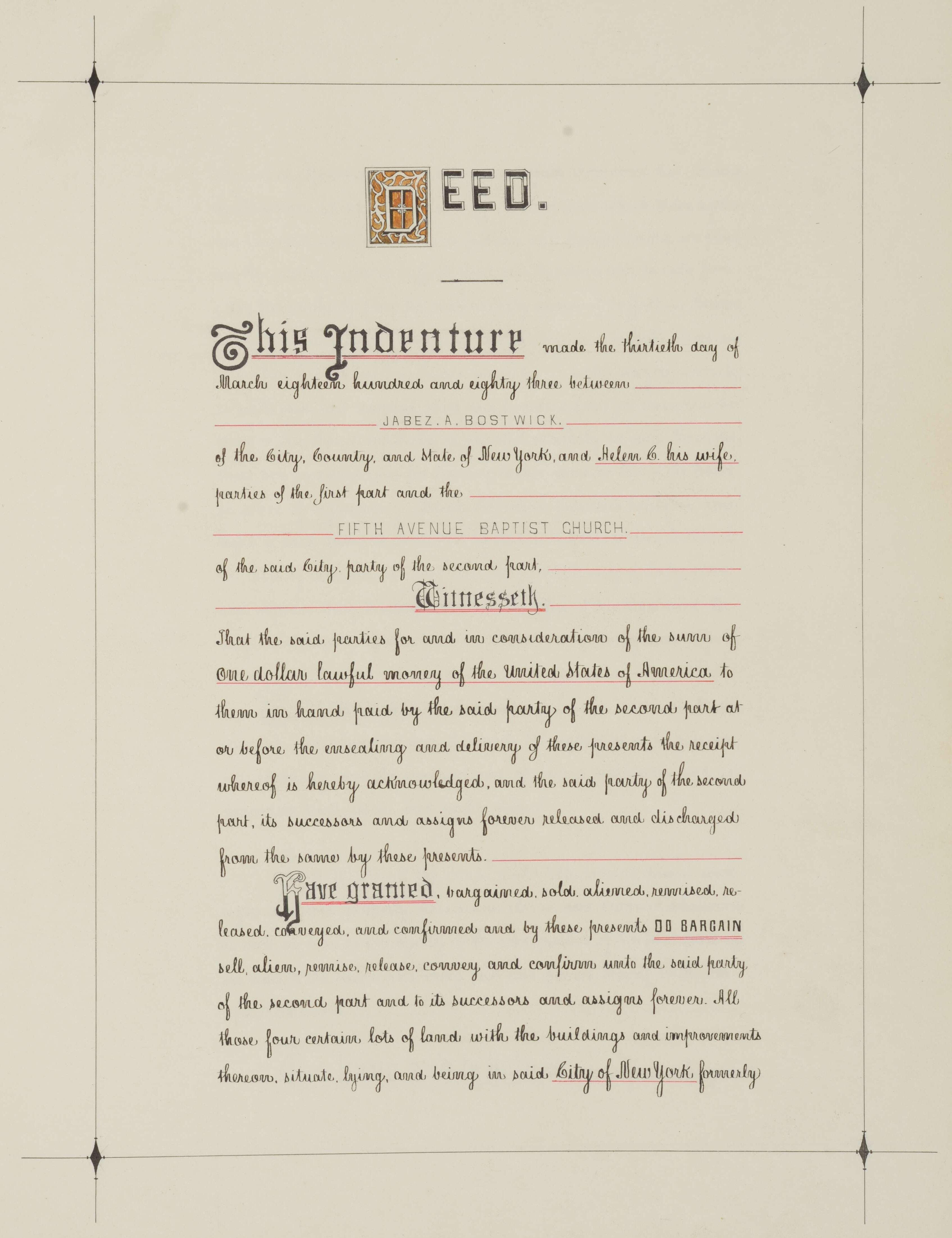

The book is chock full of calligraphy in a variety of playful fonts, with elegant borders surrounding carefully spaced text.

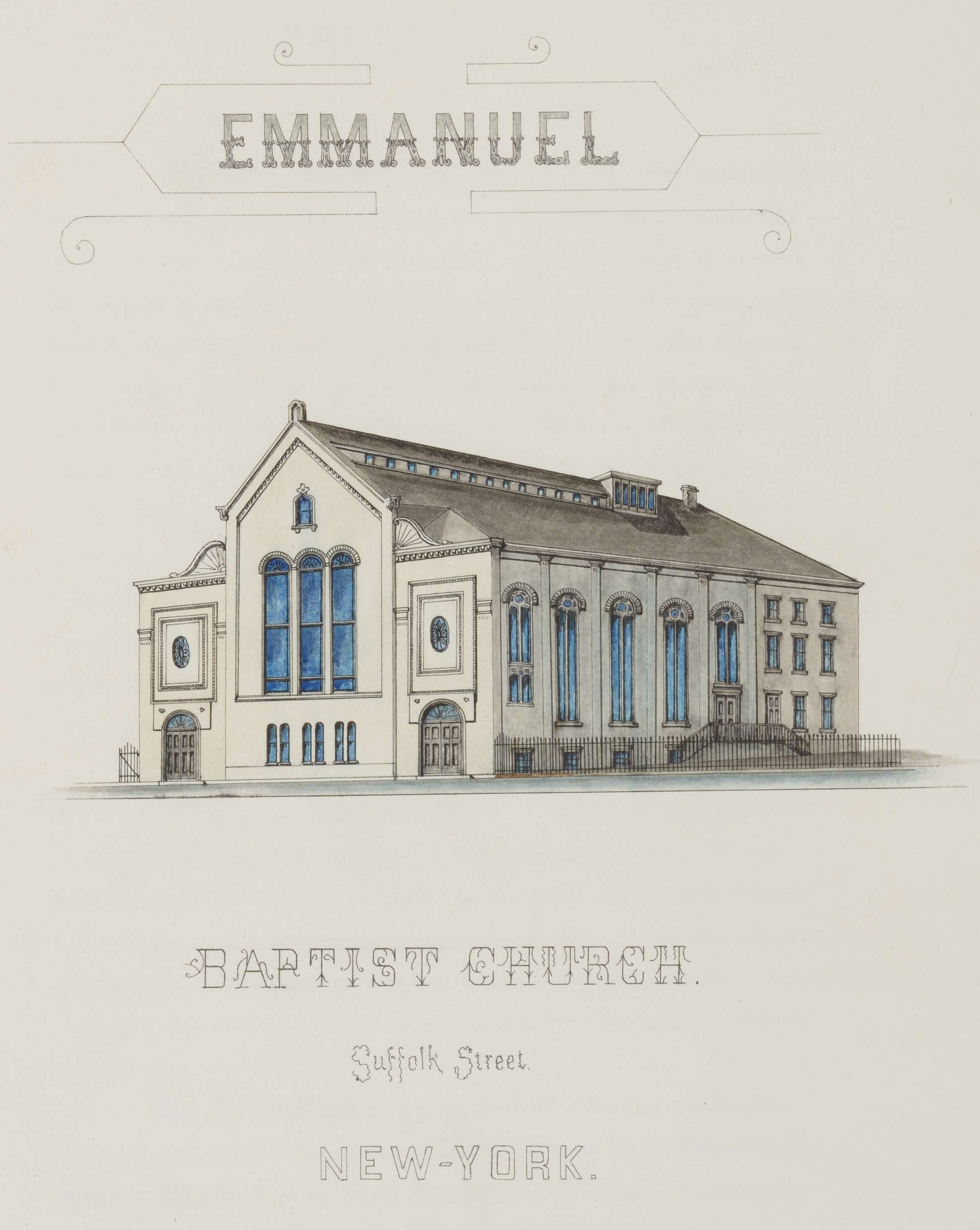

A frontispiece includes a line drawing of the donated church building, hand-colored with watercolors.

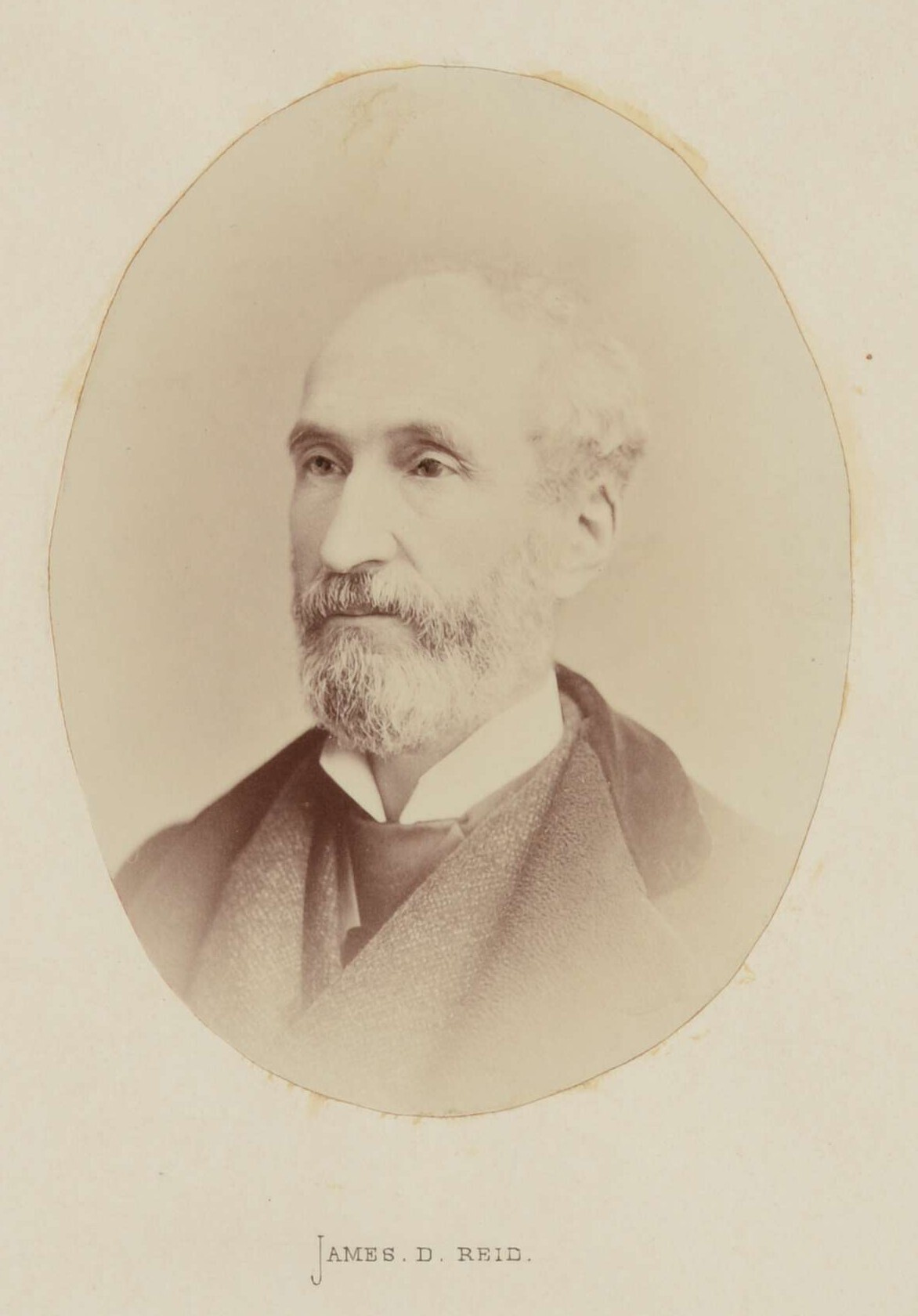

The album also contains 22 oval “cabinet-card”-size portrait photographs, carefully trimmed, labeled, and mounted. The first two commemorate Jabez and Helen Bostwick. Others represent church board members, trustees, and preachers involved in the ceremony, and the final photograph presents the author himself.

The album is a monument not only to the dedication ceremony but to the act of philanthropy that led to it. In many ways, Reid’s album is an elaborate and beautiful celebration of the donation process itself, designed as a gift to the donor.

If we were looking only at the album, we might think that James D. Reid was an established artist, known for his calligraphy. But this is not the case!

Today, the Scottish-born Reid is primarily known for his work as a business magnate, superintendent of several telegraph companies, and author of an 1879 history called The Telegraph in America. While never quite approaching the wealth of peers like Bostwick and William Rockefeller, Reid rubbed shoulders with them in business and they served side by side on church committees. In many ways, he spoke their language.

Reid’s business affiliation may explain the strange form given to the first half of the album. The last half lays out the events of the dedication services; it transcribes the invocations, prayers, hymns, sermons, and addresses that filled the schedule. The level of detail devoted to the event is perhaps surprising, but the content is expected. In contrast, the first part of the book represents an oddity.

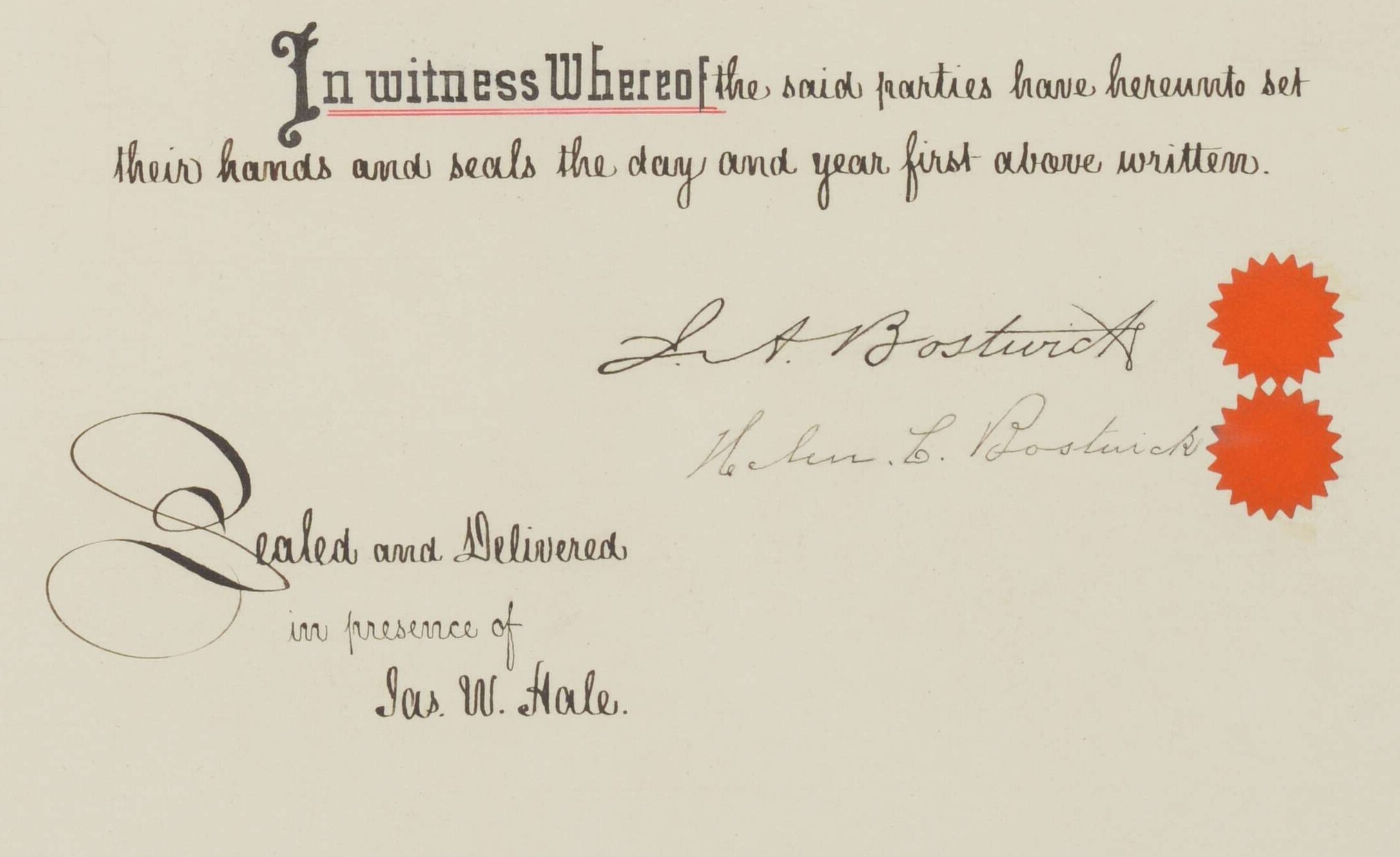

The album begins with faithfully transcribed legalities concerning the gift: minutes of the board meetings, parliamentary procedure, the letter of gift, and its official acceptance. Reid copies the deed, the agreement regarding the disposition of the land should the church close, and even the notary documents! Parts of this section read very much like an annual report…yet all in flowery calligraphy, transcribed into a celebratory album designed as a memento.

Administration as celebration?! The idea may be foreign to the modern reader, but judging from the time spent producing the object—and the signatures of both Bostwicks on the facsimile of the deed in the book—it was tremendously meaningful to both the creator and its recipients.