Poetic Fragments At The Great ʿumarī Mosque In Gaza

Poetic fragments at the Great ʿUmarī Mosque in Gaza

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Celeste Gianni shares this story about Fragments.

The Great ʿUmarī Mosque (al-Masjid al-ʻUmarī al-Kabīr) in Gaza is the largest and oldest mosque in the Gaza Strip. Originally a Byzantine church erected in the 5th century, the building was converted to a mosque after the Muslim conquest in the 7th century. Since then, the mosque has seen a long history of destruction and reconstruction up to its restoration in 1925 after it was severely damaged during World War I. Located in in what is now the Old City in downtown Gaza, the Great ʿUmarī Mosque—including the collection of manuscripts it holds—is still considered at risk of potential destruction and damage, due to the ongoing political instability in the region.

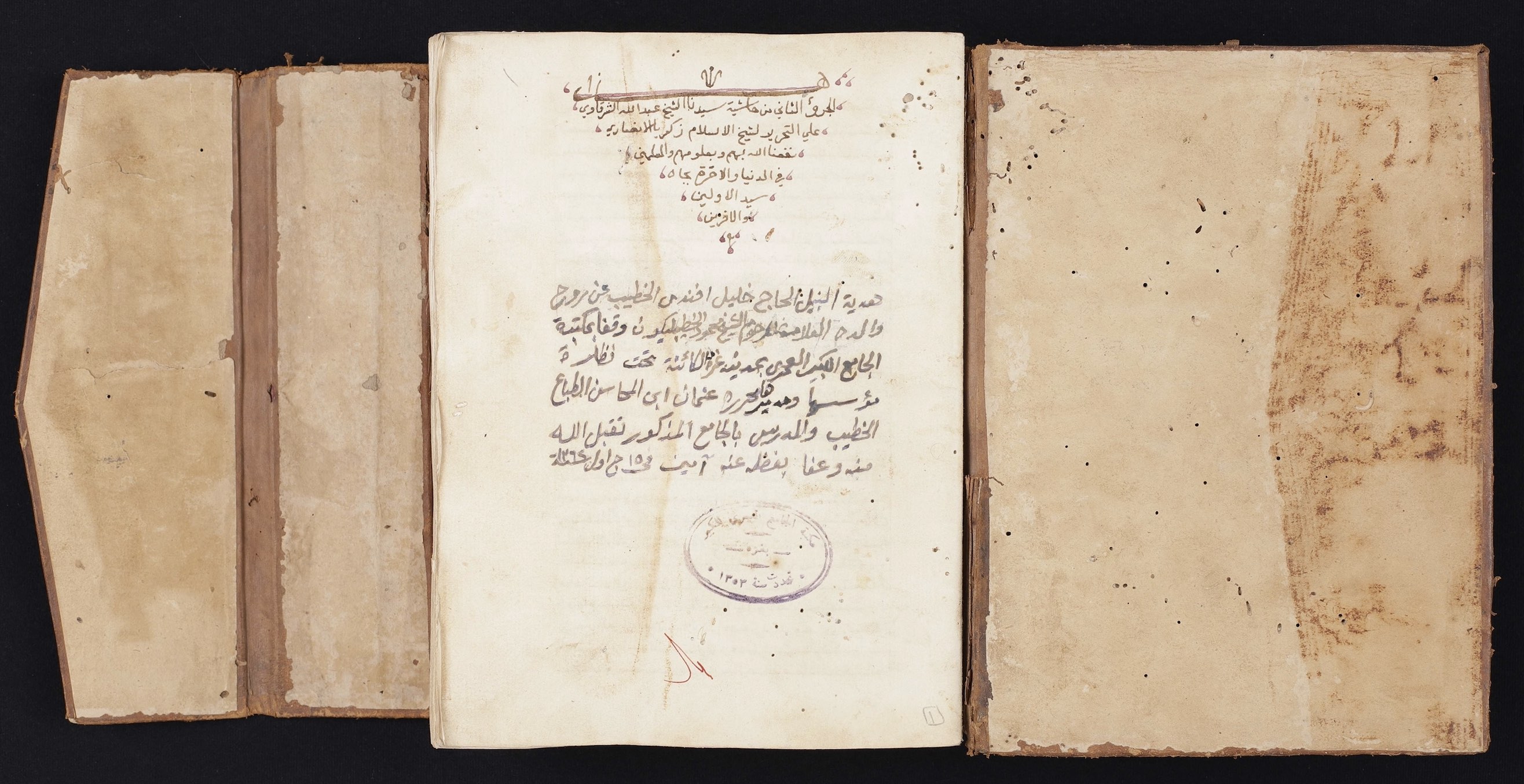

Despite these circumstances, it is very much an active and lively focal point for Gaza’s residents. The collection of manuscripts housed in the mosque is also a reflection of this fervent environment. In particular, the collection started to grow around the end of the 19th century, as attested by the ownership notes and endowment notes written in the manuscripts themselves.

Many of these later additions were endowed to the mosque by prominent Palestinian families after World War I; one manuscript (OMM 00006) was even returned to the collection in 1964 after it was stolen by a British soldier in 1917. The collection is composed solely of Arabic manuscripts, including some nicely decorated copies of the Qur’an, as well as several treatises in the fields of theology, Islamic jurisprudence, Sufism, life of the Prophets, Arabic grammar, medicine, chemistry, literature, and poetry.

An interesting feature of this collection is the presence of numerous fragments (54 out of the 211 manuscripts). These fragments consist of whole or partial leaves, often damaged by water and worming. Because of their fractured nature, they are also difficult to date and to identify.

Such fragments are often discarded by cataloging and conservation projects for their supposed lack of importance in comparison to whole manuscripts. However, in the spirit of enriching a library of manuscript treasures, they found their legitimate place in the Great ʿUmarī Mosque collection and have also found their way as digitized objects in HMML Reading Room—a space that does not discriminate regarding the nature and relevance of fragments in comparison to other objects.

Poetic fragments

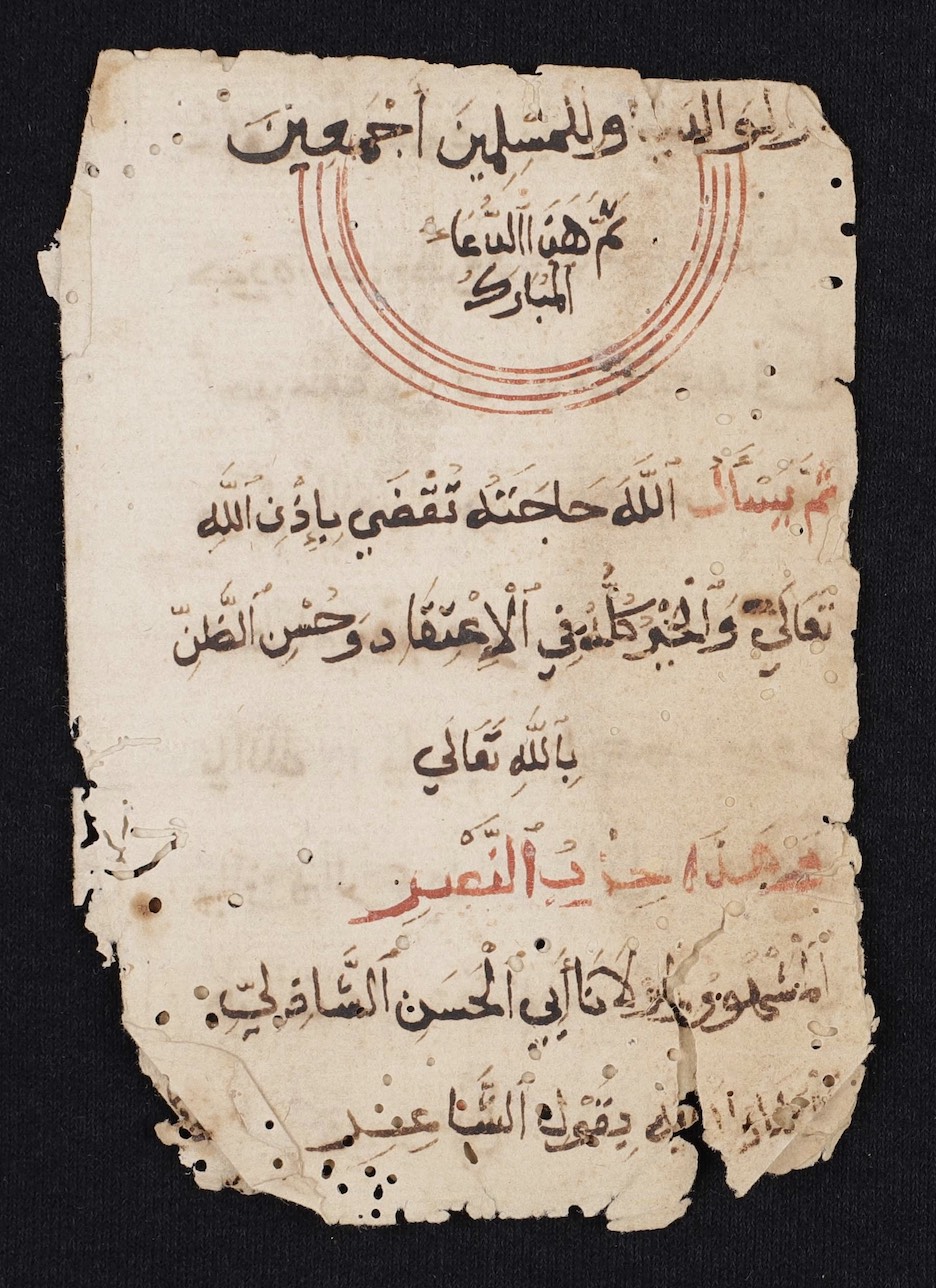

Among the 54 fragments in the Great ʿUmarī Mosque collection, there are 17 fragments of poems covering different subjects. Some of them are identifiable works, including fragments of the popular Dīwān (collection of poems) of Ibn al-Fārid (see OMM D0010), of the Dīwān of Bahāʼ al-Dīn Zuhayr ibn Muḥammad (OMM D0001), of the famous Qaṣīdat al-Burdah (Poem in praise of the Prophet) by Kaʻb ibn Zuhayr (OMM D0011), and of the well-known Ḥizb al-naṣr (Litany of victory) by al-Shādhilī (see fragment OMM D0045). These famous works are also found in their entirety in other manuscripts available in HMML Reading Room.

Other fragments include works whose authors are difficult to identify but that are based on renowned works, such as Tashṭīr al-Burdah (OMM D0012), which is a doubling of al-Būṣīrī’s poem al-Burdah, and Takhmīs Lāmiyāt Ibn al-Wardī (OMM D0004), which is an expansion of Ibn al-Wardī’s poem Naṣīḥat al-ikhwān wa-murshidat al-khillān. Both Tashtīr and Takhmīs are common literary forms of Arabic poetry which are used to create an expansion of an earlier work by adding in new verses to double (tashtīr) or five-fold (takhmīs) the verses of the original poem.

Finally, there are fragments which include works that are yet to be identified. In particular, there are fragments of a poem in praise of the Prophet (OMM D0031); a few anthologies collecting known and unknown works (OMM D0005 and OMM D0062); and an interesting nomadic poem (OMM D0068).

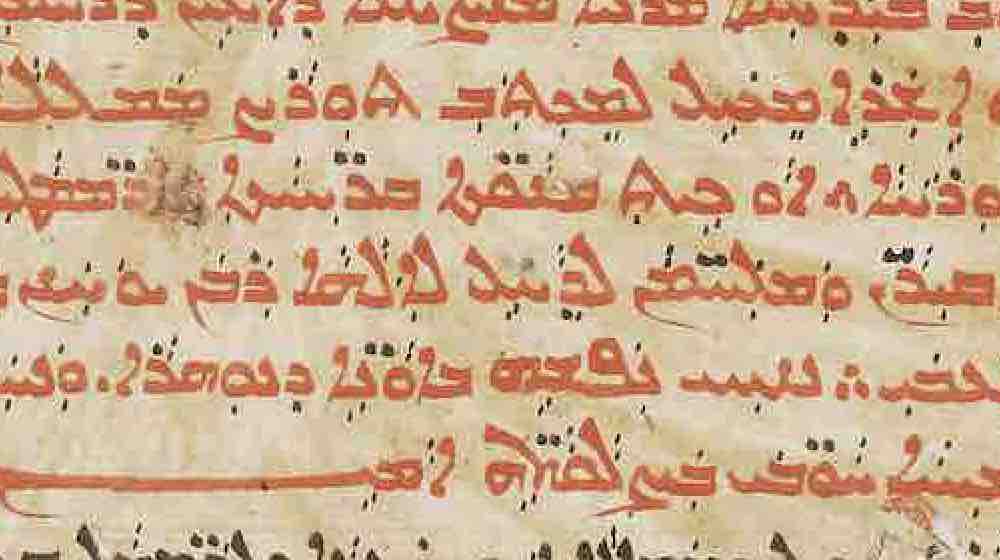

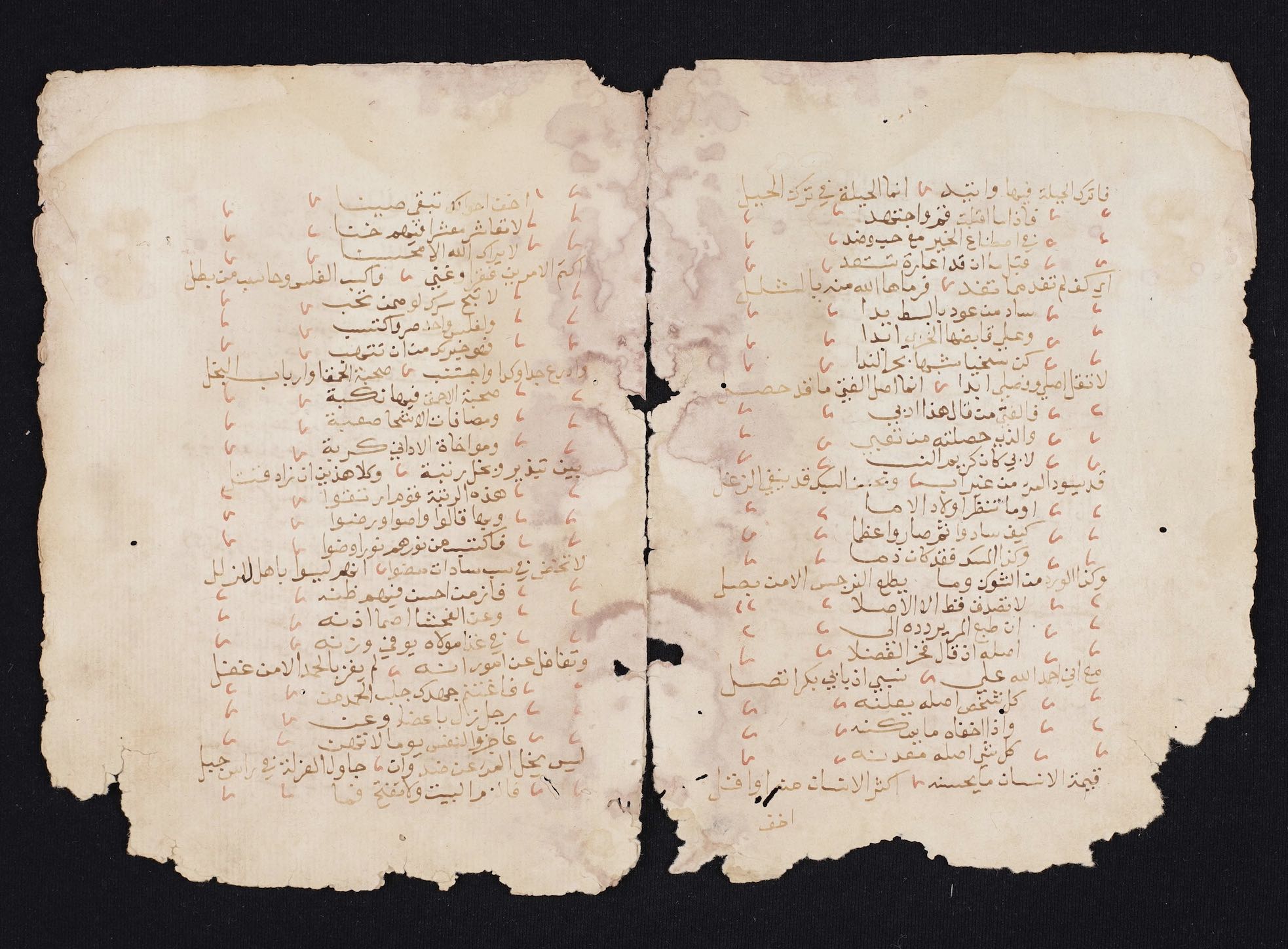

The latter is possibly a 16th-century fragment, made of four partly damaged loose leaves. The poem is divided into numbered poetic lines (called bayt, plural abyāt) including abyāt 29 to 40 on folio 1rv and abyāt 52 to 91 on folios 2r to 4v. Interestingly, each bayt appears to include two lines (instead of one, as is usually the case) composed of four hemistichs (half lines of verse) of equal length, sometimes divided by a red dot.

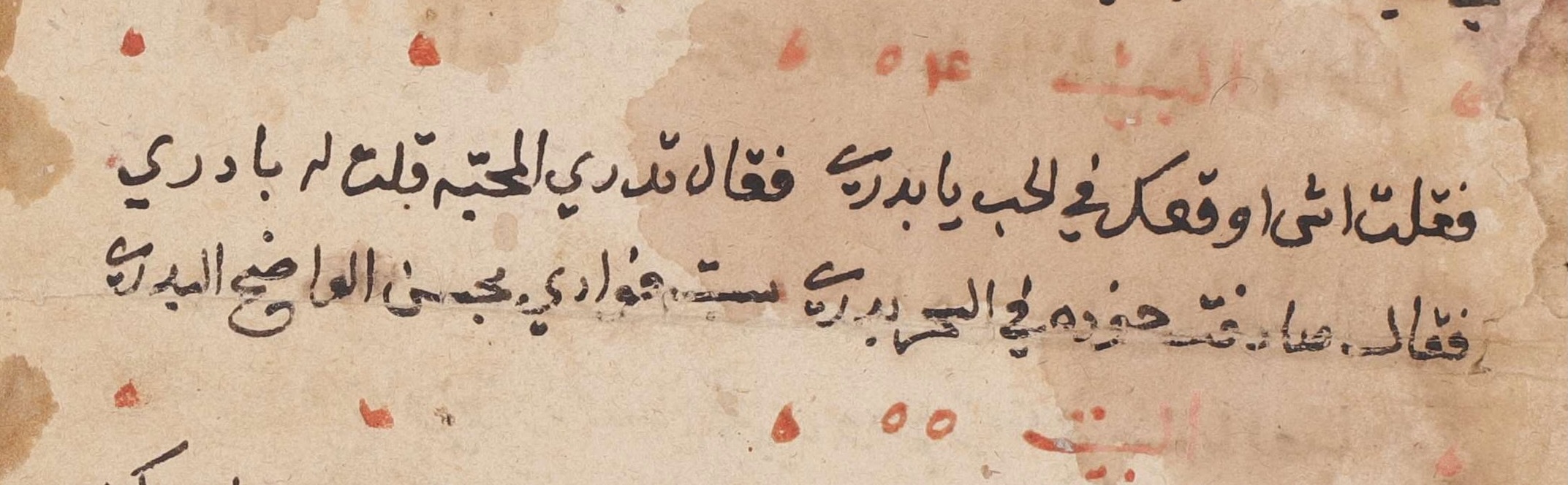

The poet uses puns and plays with words in a very skillful way. In bayt 54 for example, the poet plays with the different meanings of four words with the same root bā-dād-rā. A tentative translation of the bayt could be:

“I said: how is it possible to fall in love so early? / He said: you know how it is with love, and I replied: I know.

He continued: I accidentally met a girl from paradise in the early morning / she touched my heart with her bright moony grace”

Although it was not possible to identify this poem, the fact that this fragment is available in HMML Reading Room will allow for future comparison with other texts, and perhaps one day we will be able to identify the author and know the full poem. It could also be the case that this is the only surviving copy of this particular text, and that such a fragment at least testifies to its existence. In either case, including and cataloging fragments on digitization projects allows for such valuable findings.