Medicine, Ritual, And Magic In Ethiopia

Medicine, Ritual, and Magic in Ethiopia

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers share their discoveries, focusing on a theme that travels throughout HMML’s collections. Examining the theme of Medicine, Ted Erho shares this story from the Eastern Christian collection.

Towards the middle of the 15th century, the Ethiopian Emperor Zar’a Yā‘eqob, a prominent theologian and scholar, faced what he viewed as an unacceptable situation. Many throughout his kingdom identified as Christians yet also believed in magical practices, seeking them for healing and other purposes rather than relying on the Church and its methods for addressing maladies.

This is hardly surprising. So far as we know, no ancient medical treatises, such as those by Galen and Hippocrates, were translated into Ge‘ez. Medicinal knowledge in Ethiopia was therefore primarily traditional medicine, a field in which magic and the spirit world plays a significant role, and one which long antedated the arrival of Christianity in Ethiopia.

With both the pen and sword Zar’a Yā‘eqob confronted this situation, exhorting believers to turn instead to the clergy and Christian rituals and attempting to silence opponents of his political and theological position, many of whom he derided as lovers and practitioners of the dark arts. One of his greatest legacies in this area was the compilation of a book entitled Maṣḥafa bāḥrey (መጽሐፈ ፡ ባሕርይ, “The Book of the pearl”) circa 1441, described in its introduction as being “for healing from spiritual and bodily illness.” A lengthier synopsis occurs later in the text:

In it [Maṣḥafa bāḥrey] is medicine for soul and body from sins and destruction. God established it out of his mercy and grace as medicine for the sick, not wanting a sinner’s death, but conversion and recovery. As the Gospel says, “[He has not come to call the righteous], but sinners to repentance.” It also says, “The sick need a physician, and not the healthy” […] [This book is] for recovery from sickness of body and soul by means of the prayer of the mouth of the priests and the olive oil.

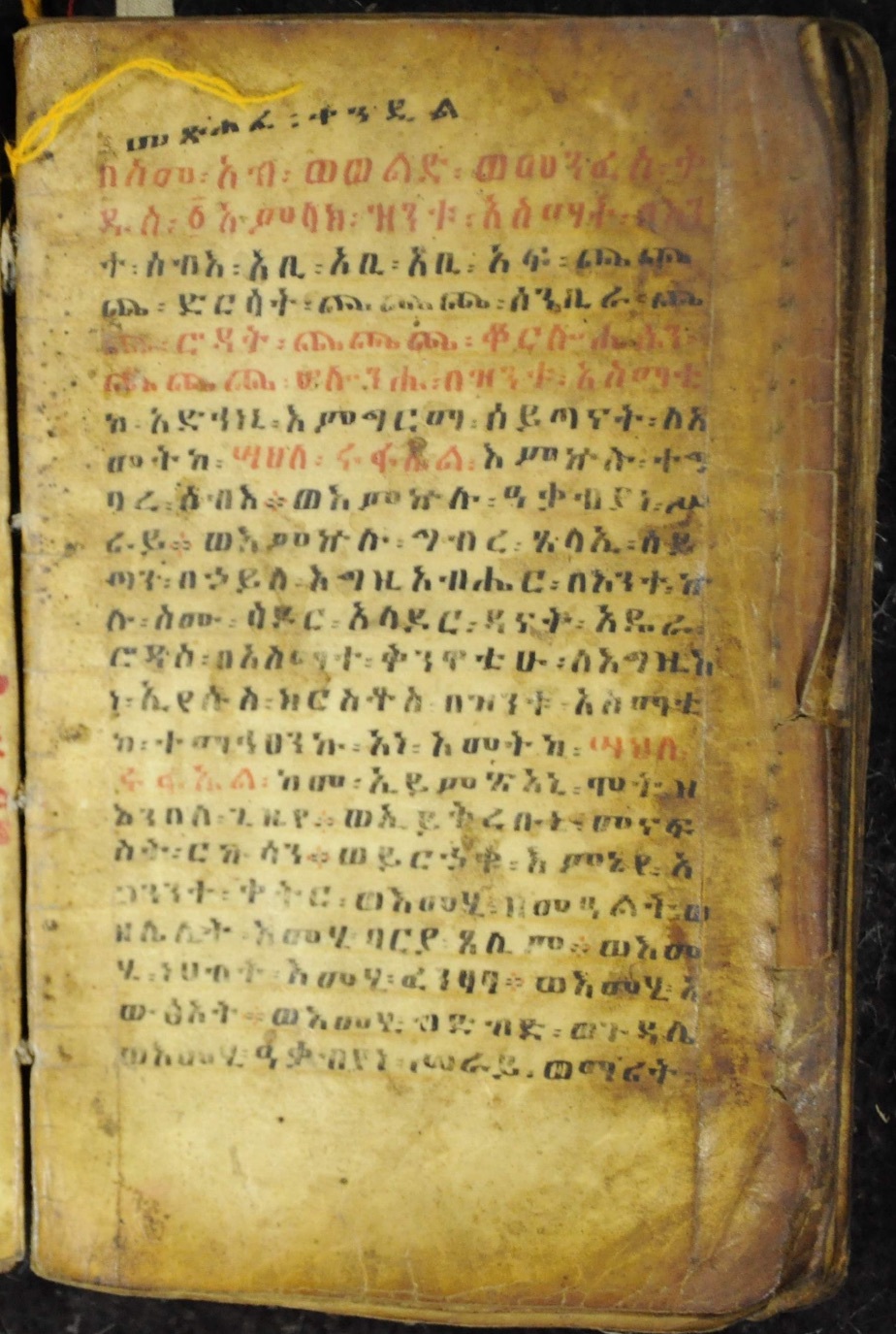

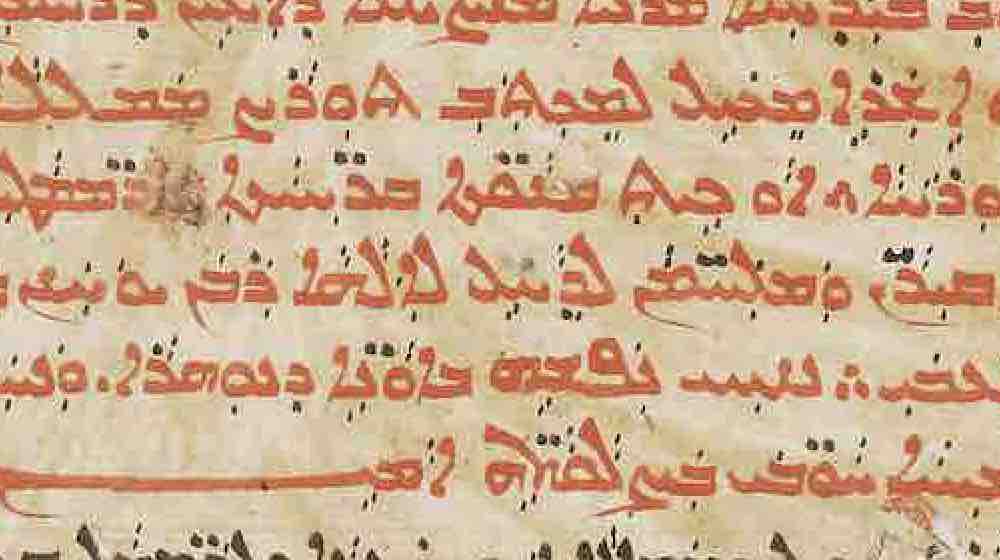

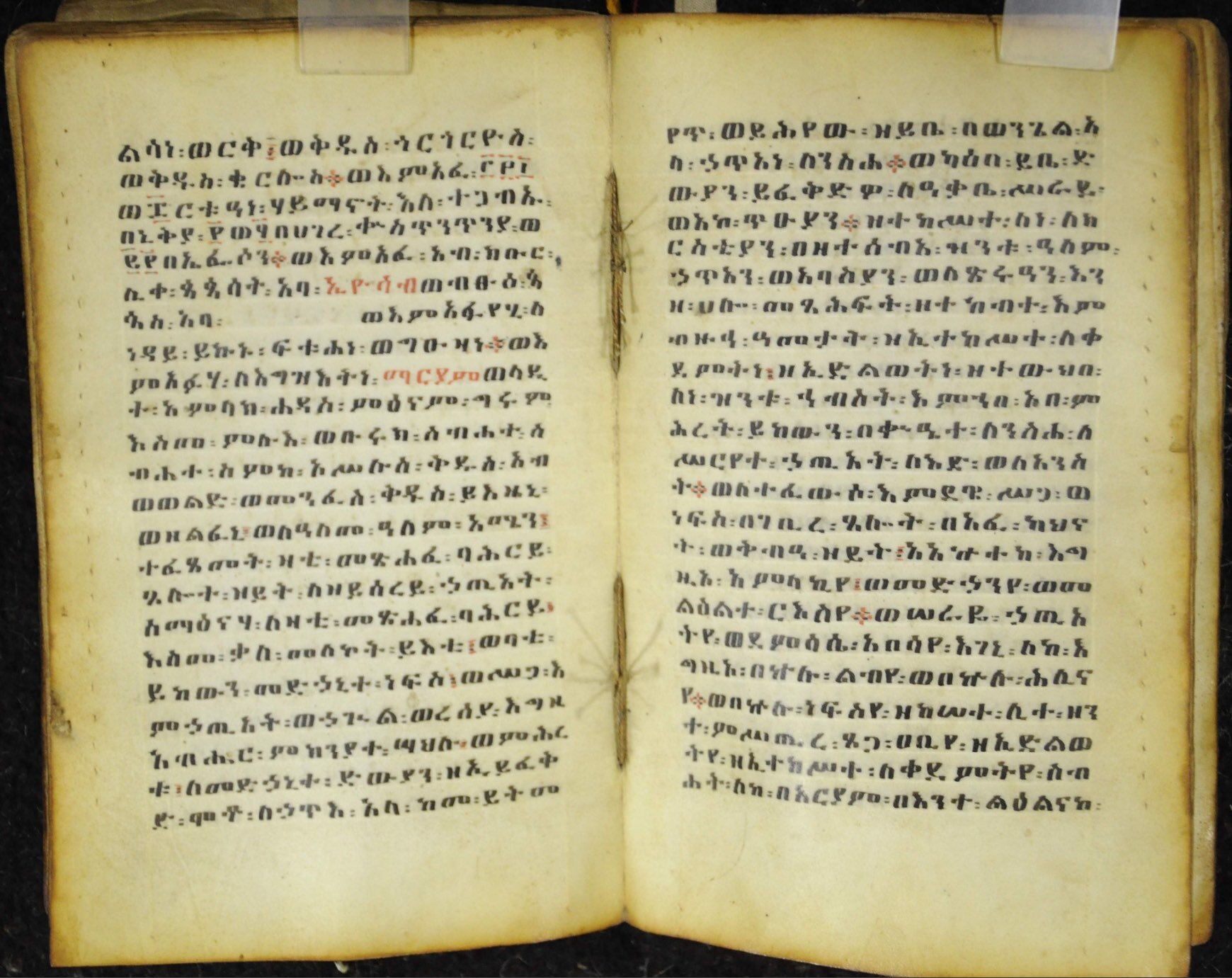

This ritual for anointing the sick is not the only text of this type in the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition. The Maṣḥafa qandil (መጽሐፈ ፡ ቀንዲል, “The Book of the lamp”), a Ge’ez translation of a Coptic rite for the same purpose, is even more popular than Maṣḥafa bāḥrey. Both books involve prayer for and the pouring of oil over a person who has fallen ill, and the two are found side-by-side in EMDA 00028, a manuscript written in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, now in the library of the famous monastery of Marṭula Māryām.

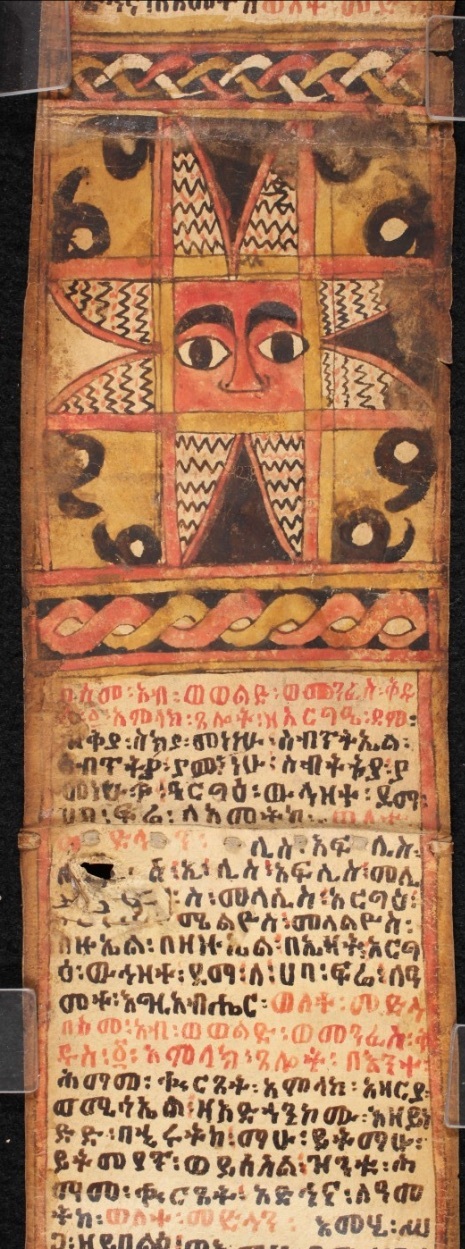

But these two rituals only comprise half of the manuscript. The pages that open and close the book are filled with a series of magical texts and invocations often relating in some way to the owner’s personal well-being. For example, the manuscript opens:

In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit: one God. These are the asmāt [names] regarding man: Abi, Abi, Abi, Af, Ċaċaċa, Dersāt, Ċaċaċa, Sanbirā, Ċaċa, Rodāt, Ċaċaċa, Qorloḥēsēn, Ċaċaċa, Holonḥē. By these, your asmāt, save me, your maidservant Śāhla Rufā’ēl [the book’s owner], from Satanic terror: from every deed of man, and from all witch doctors, and from every act of the enemy, Satan, by the power of God because of his every name. Sādor, Alādar, Dānāt, Adērā, Rodās: by the asmāt of the nail marks of our Lord Jesus Christ, by these, your asmāt, I, your maidservant Śāhla Rufā’ēl, appeal for protection so that death might not come upon me until my time and evil spirits not hover about me.

Many sections are comprised of such asmāt-prayers, a well-known genre of Ethiopic magical literature in which demons, considered responsible for physical ailments and other negative events, can be expelled or bound and their evil power overcome. In other cases, these are the names of maladies personified. Knowing their names, or invoking the correct counterforce from the heavenly realm, resulted in their removal and healing.

Other prayers in this manuscript, equally concerned with physical well-being, are less consumed by asmāt, sometimes focusing instead on the range of ailments that could be encountered. One, entitled “Banisher of demons” says that it “will expel every sickness and disease,” and because of it, “every evil spirit will be removed from the soul and body of your maidservant Śāhla Rufā’ēl [the book’s owner] and from whoever carries around their neck or bears this book.” Partway through, a clearly Christian invocation gives some idea of the range of illnesses in view:

Christ, run to help me from whatever shows me enmity: be it a sorcerer or witch; affliction of man, wife or woman; affliction of liver, rib, or heart; affliction of hand, foot, hip, bone, or battle; affliction of head, foot, eye, or ear; affliction of nose, mouth, throat, tongue, or tooth; affliction of hand, skin, or bowel; or the affliction of the elderly who visit on Tuesday and on Wednesday, who are chilled and shiver and who light fires and resign themselves [to death]; and the affliction of colic, ulcer, womb, or abortion[?].

Such Christian medico-magical literature plays a significant role in traditional medicine in Ethiopia today, and stretches back to long before Zar’a Yā‘eqob ascended the throne. Regardless of its lack of connection to the tradition of Galen and Hippocrates, EMDA 00028 thus stands as a book of healing and preventative medicine through and through, one of the most comprehensive such volumes recorded in the Ethiopian tradition. Magic and ritual are hardly strange bedfellows, being closely related in most religious practices, and their joint utilization to try and ward off maladies is merely an oft overlooked chapter in the long history of medicine.