Remedies In The Margins Of Syriac Manuscripts

Remedies in the Margins of Syriac Manuscripts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers share their discoveries, focusing on a theme that travels throughout HMML’s collections. Examining the theme of Medicine, Dr. David Calabro shares this story from the Eastern Christian collection.

People in past centuries would sometimes use the blank flyleaves and margins of manuscripts to record their knowledge of medical cures. These ‘remedies in the margins’ give us insight into the traditions of folk medicine practiced among Christian communities in the Middle East. Like most medical practice in the premodern Middle East, these remedies incorporate natural products, especially from plants; however, they do not present the erudite references, theory, and complicated preparations characteristic of larger medical treatises.

Remedies of Two Communities in the Same Town

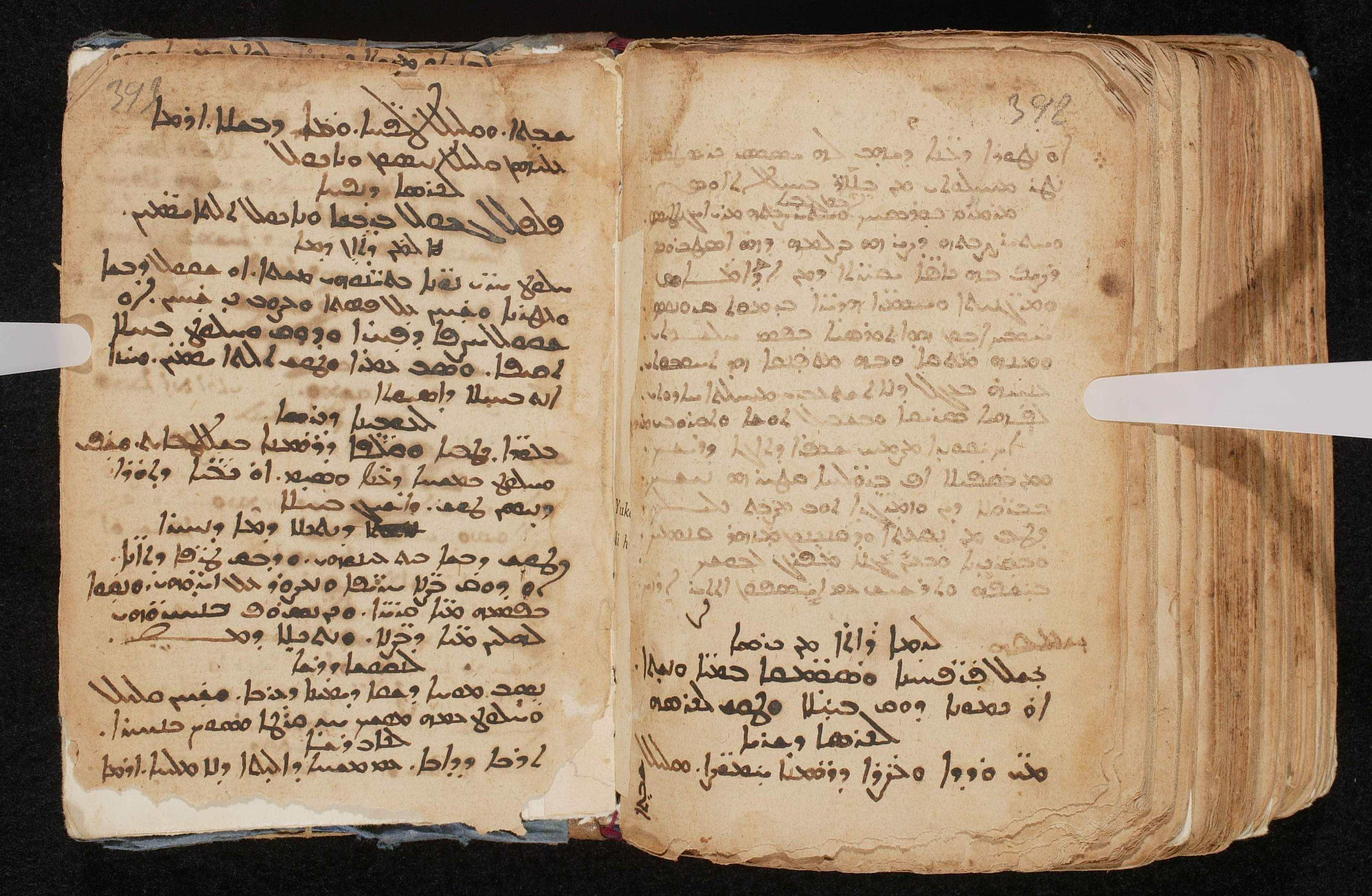

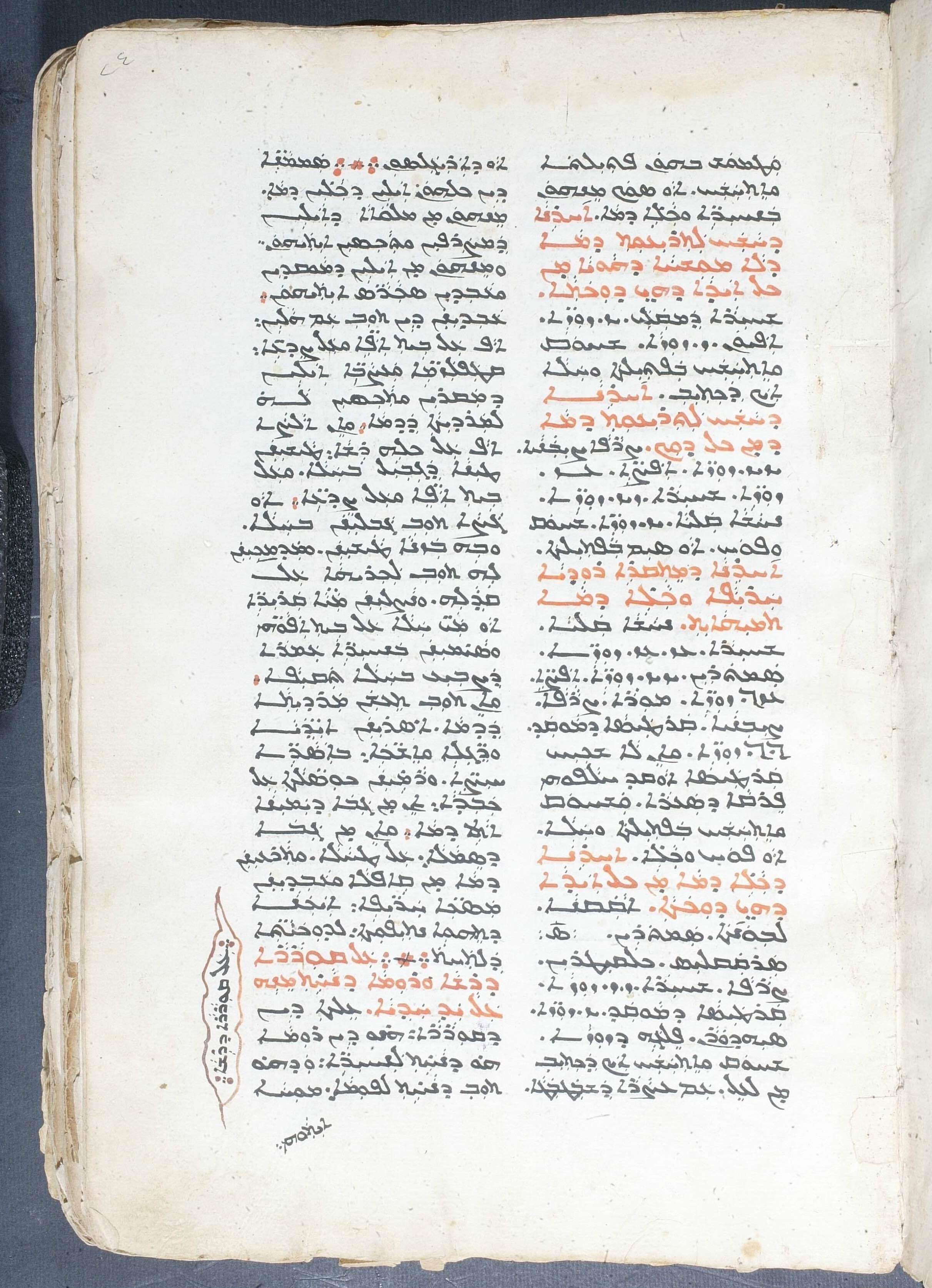

Two manuscripts from the town of Mardin, in modern-day Turkey, include notes with medical remedies in Syriac. One of these, CFMM 00490, comes from the Syrian Orthodox community in Mardin and dates to 1587. The other, CCM 00022, comes from the area’s Chaldean community and dates to 1681. The main text of both manuscripts deals with language: CFMM 00490 is a Syriac-Arabic dictionary by Eliyā of Nisibis (975-1046), and CCM 00022 is a collection of works on grammar and homilies.

The back flyleaves of both manuscripts bear medical remedies recorded later than the main text. In CFMM 00490, there is a collection of remedies for gastrointestinal bleeding, diarrhea, abdominal swelling, nosebleed, headache, and many other maladies. In CCM 00022, notes on a flyleaf tell the reader how to treat nosebleed, stomachache with vomiting of blood, hernia, ant infestation, and fleas. Often, in both manuscripts, several different cures are recorded for the same malady. If one cure doesn’t work, the patient can try another.

Two Remedies for Nosebleed

It is informative to compare the remedies recorded by these different Christian communities in the same region and time period. Both sets of remedies include a prescription for nosebleed:

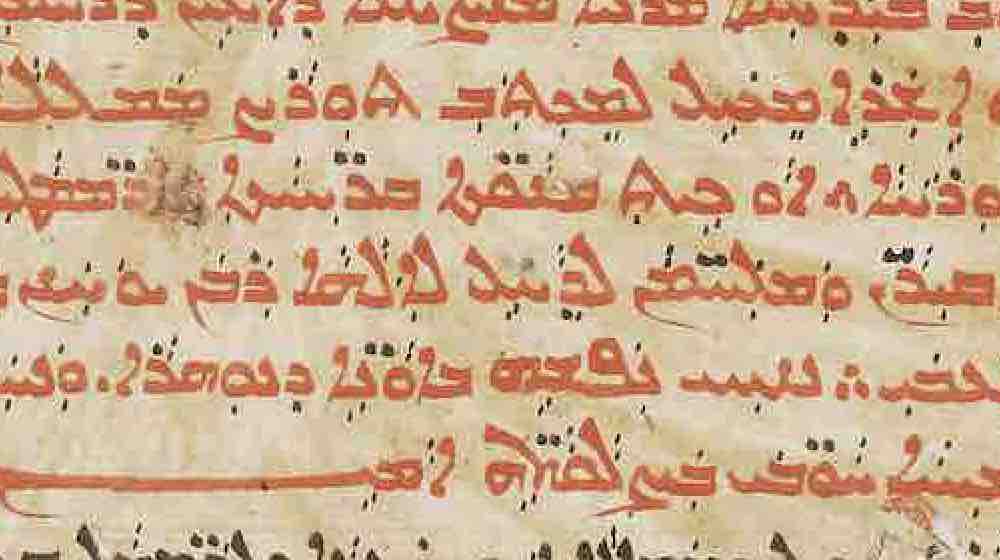

CFMM 00490, page 393:

For nosebleed to stop: Rub honey between his eyes, and apply fig leaves. Or crush sharp onions and press it on his hands while cold water remains in his mouth, and then let him absorb the onion water through his nose, and the bleeding will stop.

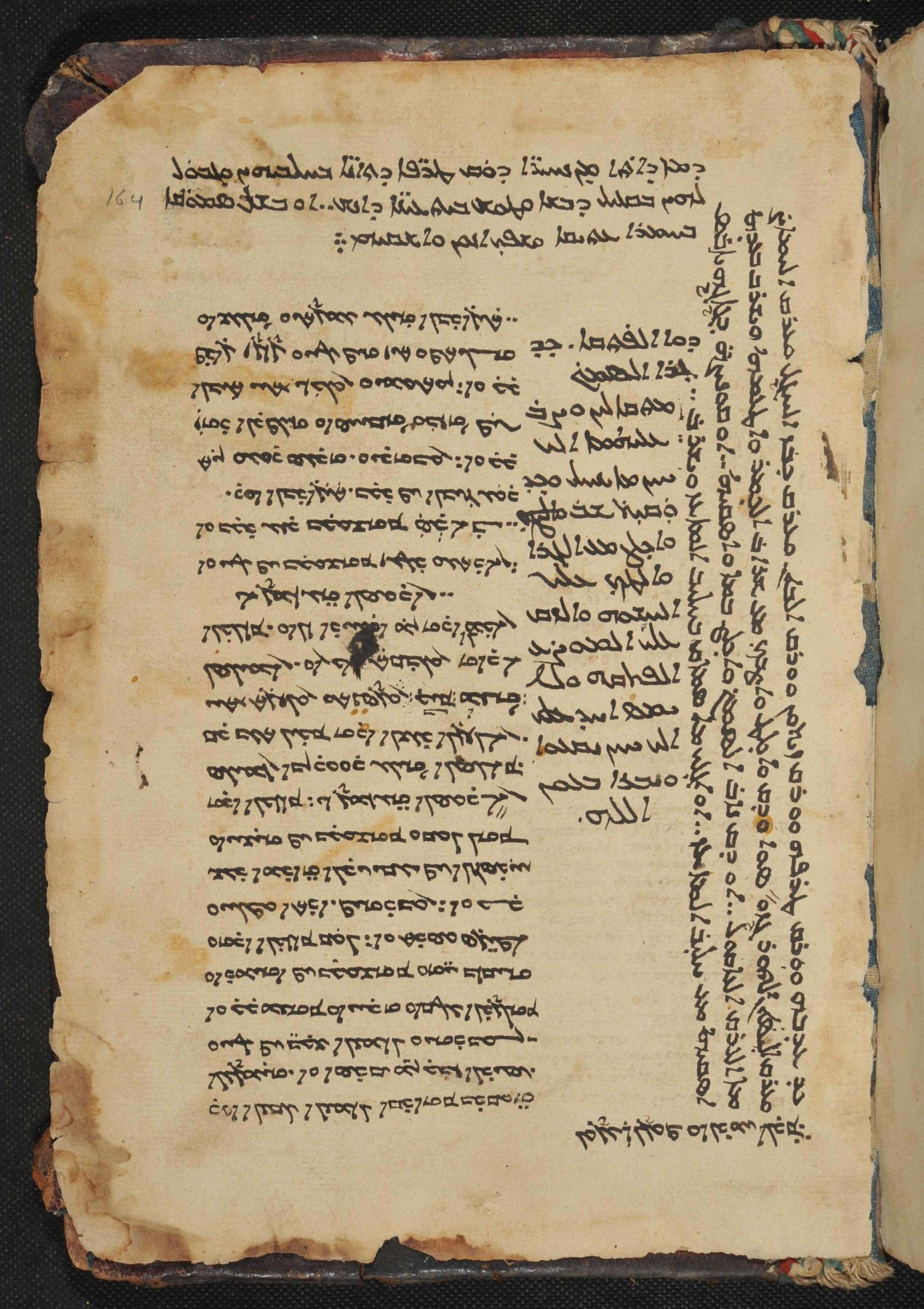

CCM 00022, folio 164r:

(For) blood that comes out of the nostrils: Crush fig leaves in their milky juice and mix it with a little honey, then apply it between the man’s eyes. Or boil red lentils in old wine, strain them, and have him drink it.

Interestingly, both remedies recommend the use of fig leaves and honey applied between the eyes. This same procedure is found in the compendium of folk remedies in the last section of the book known as the Syriac Book of Medicines (see the HMML manuscript QACCT 00149).

The ingredients—honey, fig leaves, onions, lentils, and wine—would be easily available to the average household. These common ingredients contrast with the rarer (and more dangerous) ones prescribed for nosebleed in the sophisticated first part of the Syriac Book of Medicines, ingredients which include frankincense, opium, vitriol, and myrrh.

The remedy from CCM 00022 specifies the use of red lentils boiled in old wine, a concoction that would resemble blood (NB: the basic meaning of the Syriac word for "lentils," here, is "red"). This remedy is an example of the “doctrine of signatures”—the common idea that the color or shape of a natural product indicates its curative benefit.

So, do these two remedies actually work? Well, if they don’t, you would at least have the beginnings of a delicious dinner...