Yeɗi Sanba Ɓooyi, A Fulani Scholar And Poet

Yeɗi Sanba Ɓooyi, a Fulani Scholar and Poet

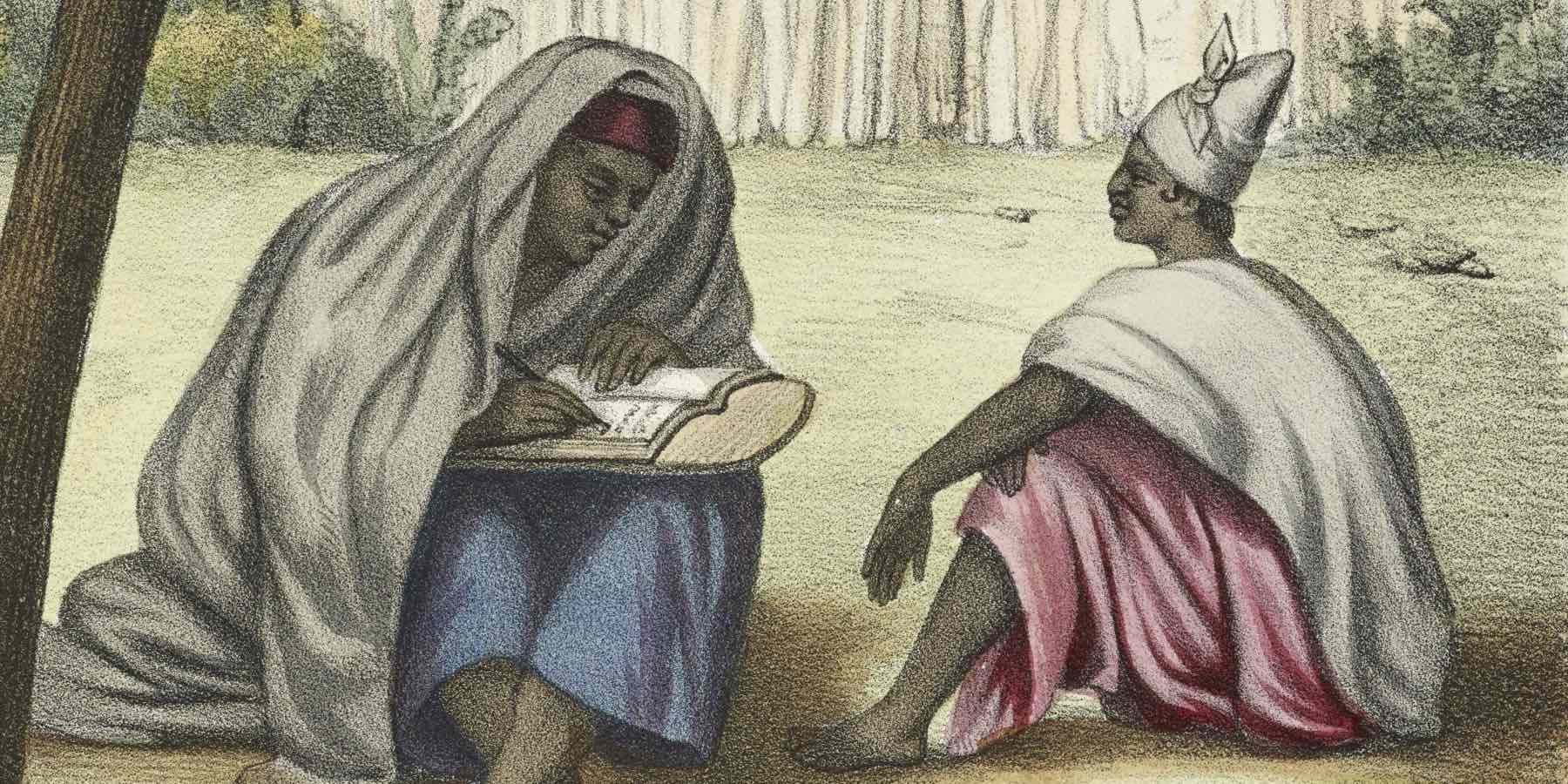

Yeɗi Sanba Ɓooyi was a scholar who belonged to the Fulani, a traditionally nomadic people who are found from Sudan in the east of Africa to Mauritania on the west coast.

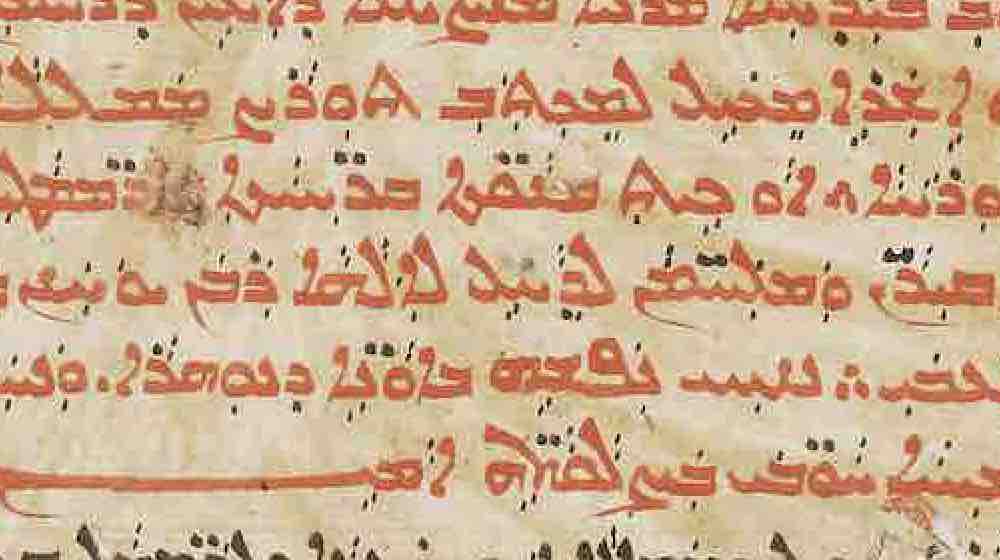

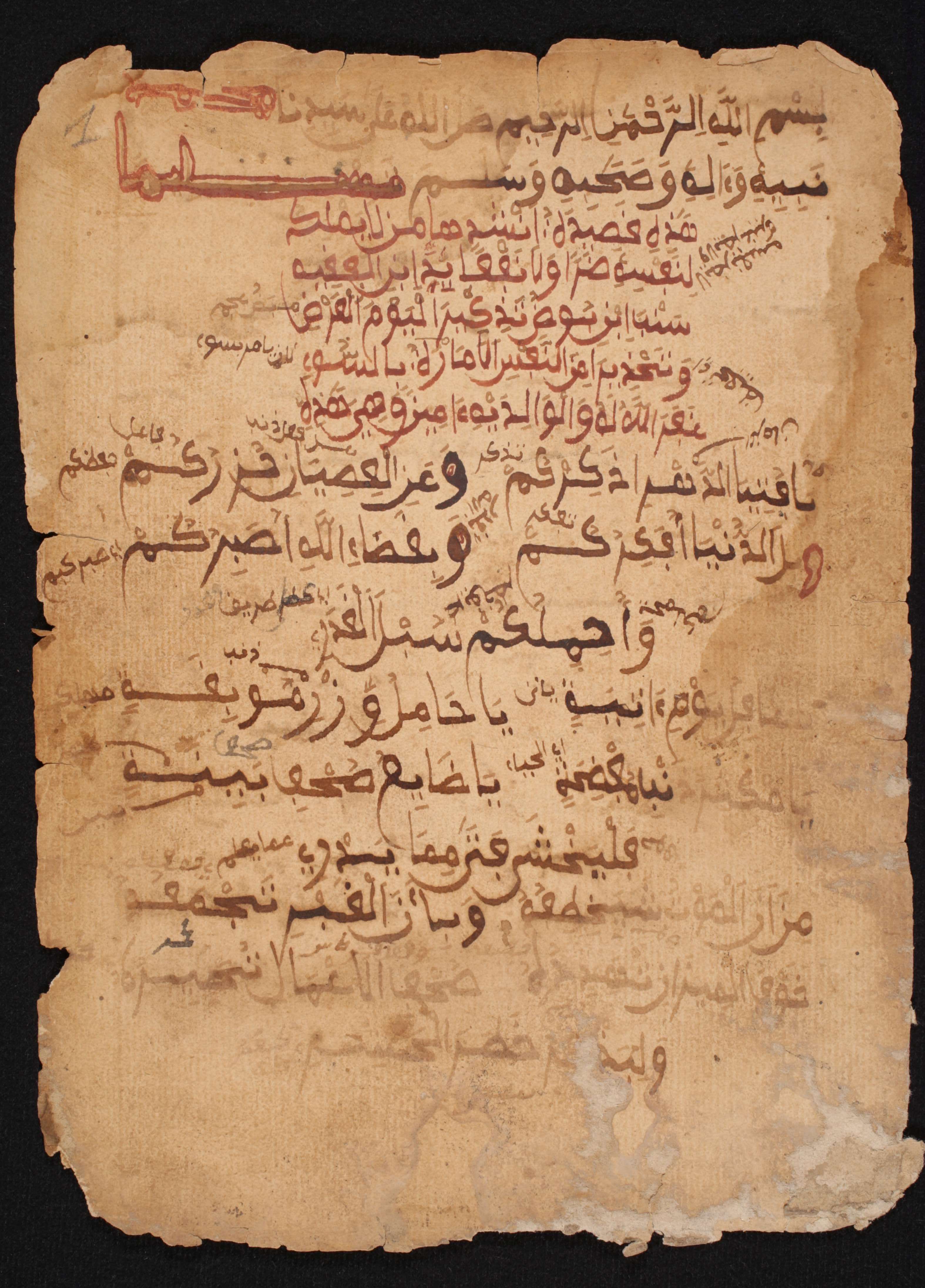

Yeɗi was evidently well known in his region for the art of the five-stanza (pentastich) poem (in Arabic, Qaṣīdah mukhammasah) and for the enlargement of existing poems to a five-stanza form (in Arabic, Takhmīs). So far we’ve looked for his work in two of the Timbuktu libraries in HMML Reading Room, Mamma Haidara Library, and Aboubacar Bin Said Library, and have found three different poems attributed to Yeɗi.

Judging by the number of copies alone, Yeɗi’s most popular work was a poem he wrote about the “warnings of the grave” (in Arabic, التحذير عن الموت), a specific genre of preaching that reminds readers of their mortality and instructs them to prepare for the judgement believed to come after death. Sixteen copies of this work exist across the two libraries and, with the absence of a formal title, we have called the poem simply “Qaṣīdah mukhammasah.”

The text was evidently meant as a didactic lesson to the young and heedless, as evinced by the poem’s first lines:

يا فتيا الدهر أذكّركم * وعن العصيان أحذّركم

وبلاء الدنيا أفكّركم * بقضاء الله أصبّركم

وأحمّلكم سبل القدرOh young people, I remind you * And warn you against disobedience

I entreat you to consider the misfortune of this world * And to accept the will of God

Take responsibility for the direction of your fate

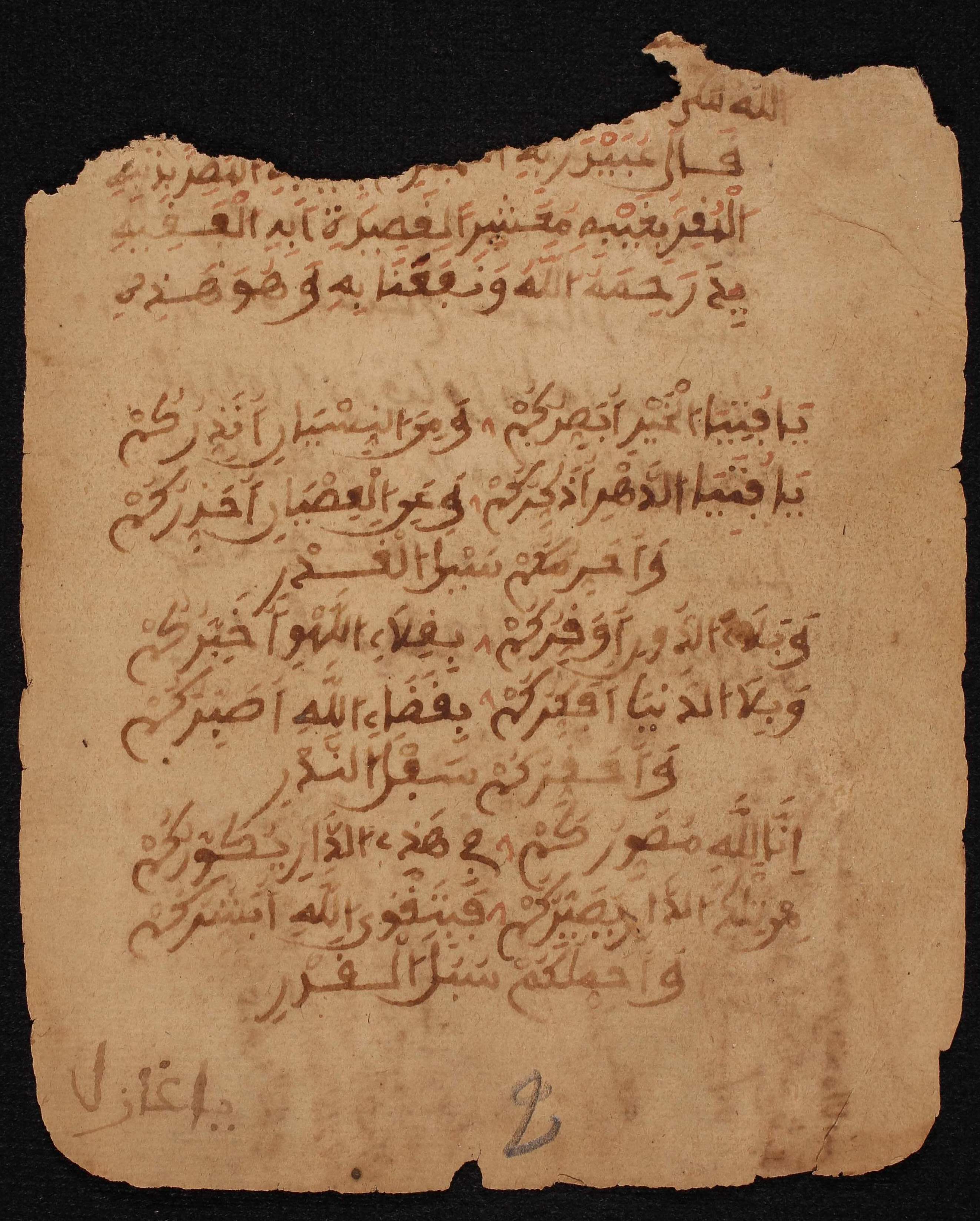

It is therefore very touching to learn that Yeɗi’s son not only took the message to heart but sought to add to it, doubling his father’s Qaṣīdah mukhammasah to a ten-stanza poem. His additions to the poem are in bolded text:

يا فتيا الخير أبصركم * ومن النسيان أنذركم

يا فتيا الدهر أذكركم * وعن العصيان أحذركم

وأحمّلكم سبل القدر

وبلاء الكون أوقركم * بقلاء اللهو أخبركم

وبلاء الدنيا أفكركم * بقضاء الله أصبركم

وأحقركم سفل الندرOh good young folk, I notify you * And caution you against forgetting

Oh young people, I remind you * And warn you against disobedience

Take responsibility for the direction of your fate

Of the misfortune of existence I enjoin you * Of loathful amusements I inform you

I entreat you to consider the misfortune of this world * And accept the will of God

And avert you from profound regret

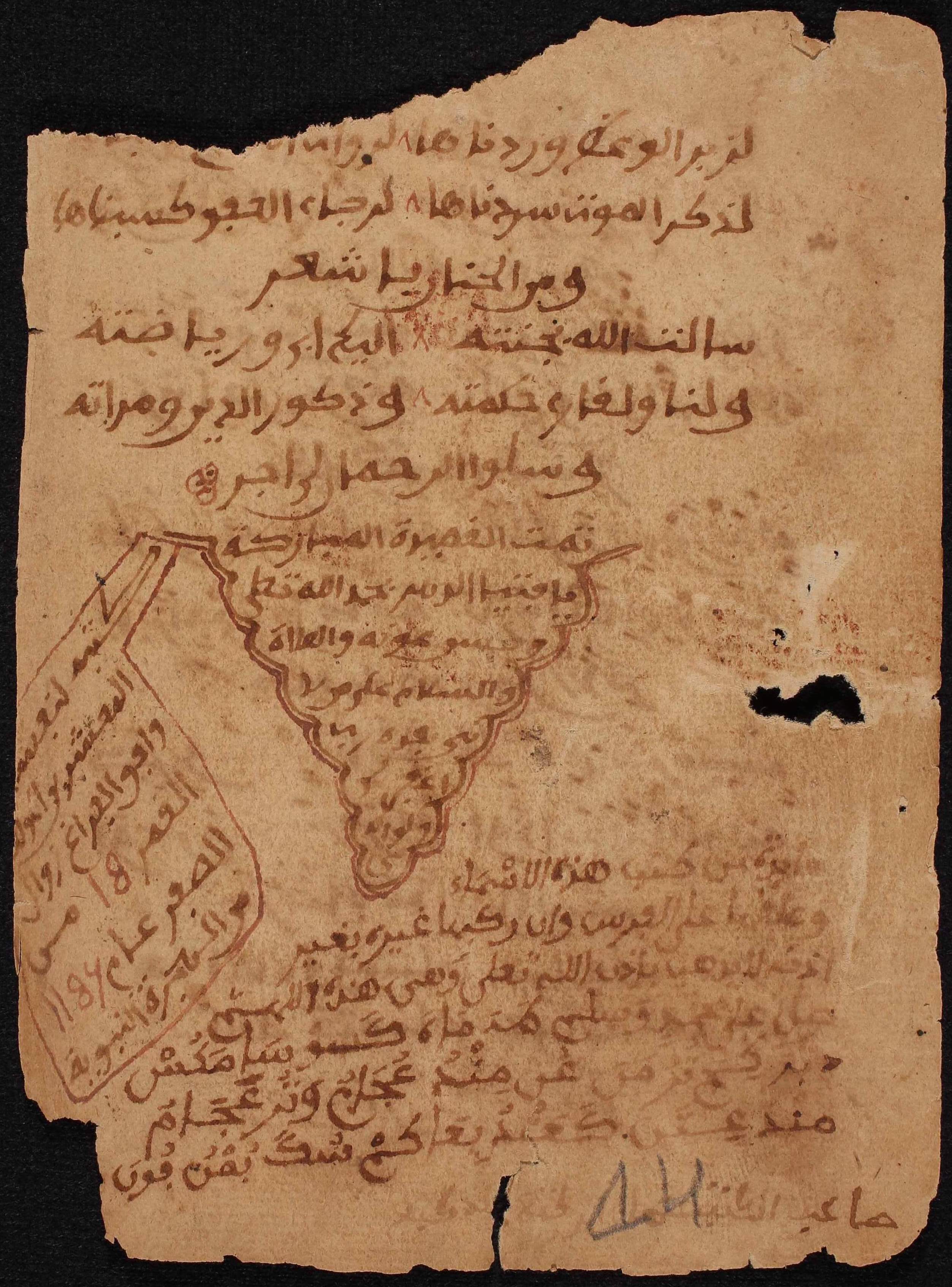

This ten-verse poem—a form known in Arabic as “Taʻshīr,” though the term is rarely used—was copied on May 21, 1772, possibly by Yeɗi’s son himself. As we see from the last lines of the poem, Yeɗi had by this time passed away. His son’s enlargement of this famous poem was thus an act of remembrance for his father:

لذكر الموت سردناها * لرجاء العفو كسبناها

ومن الحنان يا شعر

سألت الله بجنته * إليك أبي ورياضته

ولنا ولقاء حكمته * وذكور الدين ومراته

وسلوا الرحمن لي أجرOn death we have enumerated * And earned the hope of forgiveness

And with tenderness, oh poet

I asked God to give His Paradise * His garden to you my father

And grant us all by His wisdom a meeting * men and women of religion both

And pray that God the Most Gracious recompense me

As we continue to explore Timbuktu’s libraries, no doubt many other local scholars will come to light. Such documents demonstrate that, contrary to popular opinion, the region possessed a rich tradition of Islamic literature predating the jihads of the nineteenth century, after which the culture of writing and reading in Arabic became more popular.