Migration Of Ideas Through Printmaking

Migration of Ideas through Printmaking

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From Art & Photographs collection, Katherine Goertz has this story about Migration.

When discussing the idea of migration in European art history, attention is often focused on the movement of the artists who regularly traveled between regional art scenes in a transcontinental cultural exchange. But art objects—prints, paintings, and sculptures, for example—also moved through geographical and cultural boundaries. Art is a medium through which ideas and movements migrate, and sometimes it is possible to trace that migration.

Some forms of art are especially suited to travel. By the 16th century, a complex and interconnected artistic marketplace covered Europe, and prints—small, nearly weightless, relatively inexpensive, and plentiful—were at its center.

Engraved or etched copies of paintings by famous artists were popular, and printmakers were happy to satisfy the demand. The Old Masters of Amsterdam were available in print shops in England and France—not in their original oils and canvas, but in ink and paper. Homes across Europe had a print or two depicting faraway paintings or sculptures, miniature copies of works of art that the owners would never see in person. Artists built collections of art on paper, interested in knowing exactly what motifs, trends, and styles could be found elsewhere in the world. As prints traveled along Europe’s commercial network, the trends, styles, and names of European art and visual culture migrated with them.

By the 17th century, the influence of the Viceroyalty of New Spain spanned large parts of North and South America. In places like Mexico City, Mexico, and Lima, Peru, the European print market now had a new commercial arm. Soon, an evolving New Spanish art world developed its own print marketplace, circulating thousands of European prints throughout the viceroyalty.

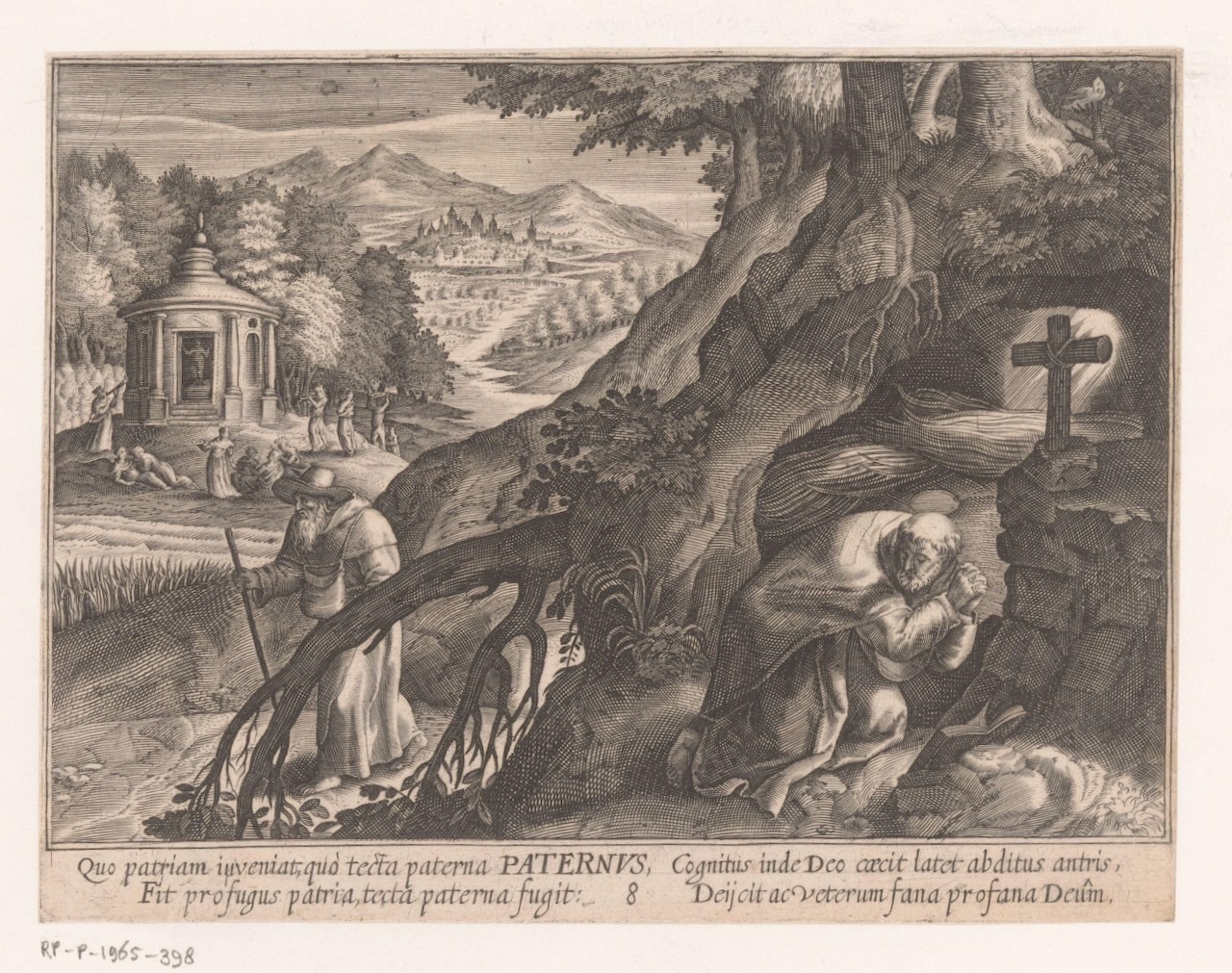

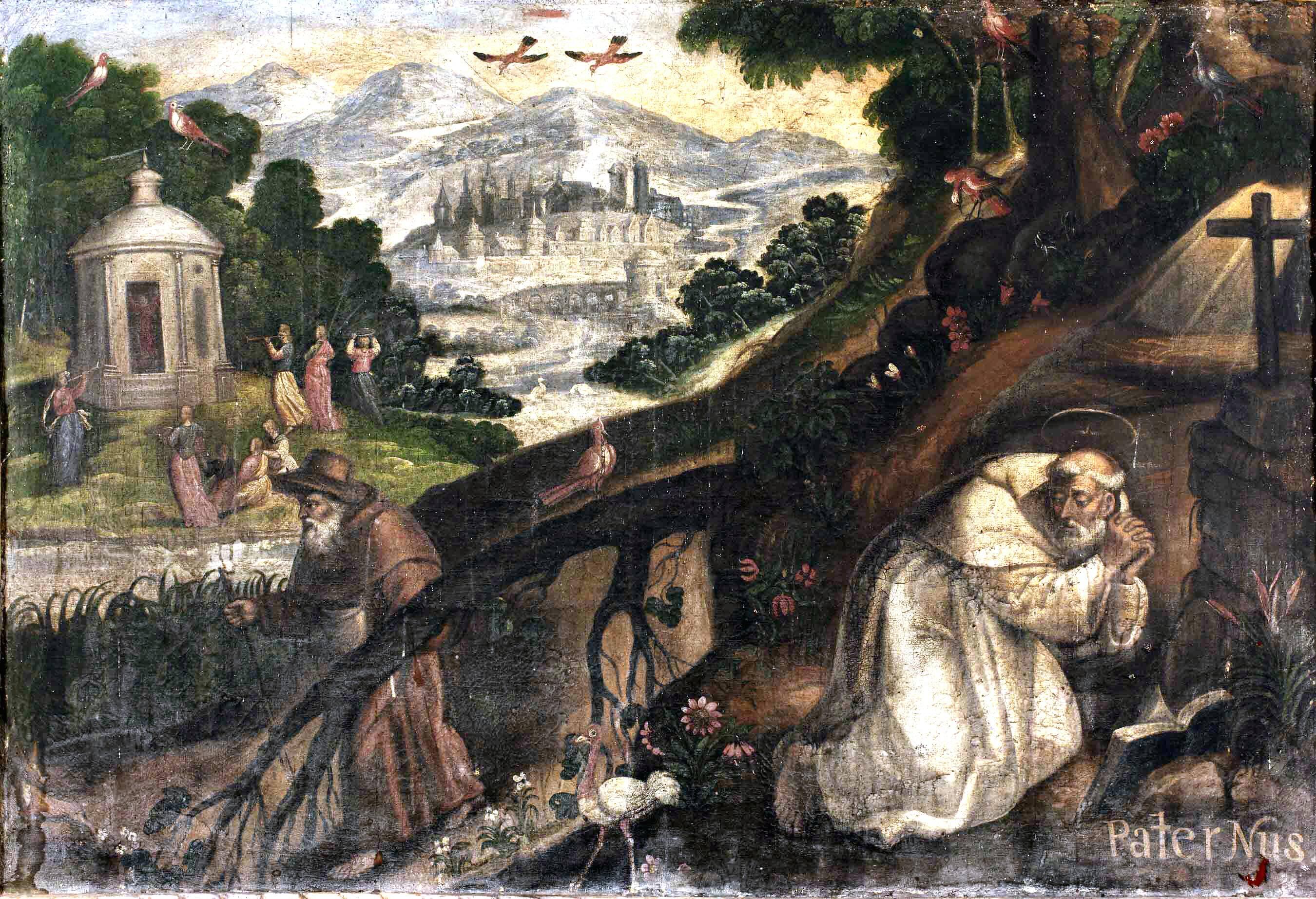

Sixteen paintings by an unknown follower of the Quechua artist Diego Quispe Tito (1611–1681) hang in the Convento Franciscano de la Recoleta in Cuzco, Peru. They share a composition with engravings by the Flemish painter and print designer Maarten de Vos (1532–1603), specifically with two de Vos series published in the 1580s and 1590s. In one of the Cuzco paintings, St. Malchus leans toward his dog precisely as the saint leans in de Vos’ engraving from a series published between 1585–1587 called Solitudo sive vitae patrum eremicolarum (Solitude, or the lives of the desert fathers). In another, St. John of Egypt crawls from the same cave as in de Vos’ engraving in the 1598 series Trophaeum vitae solitariae (The glorious solitary life). In a third painting, St. Venerius sits next to the same fountain that de Vos depicted in Trophaeum vitae solitariae.

A second set of paintings, depicting the life of St. Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), can be found in another historical convent in Cuzco—the Convento de Santa Teresa. These paintings were created by José Espinoza de los Monteros in 1682 using the composition of a series of early 17th-century Flemish prints, Vita B. Virginis Teresiae a Iesu (Life of St. Teresa of Christ), by the Flemish designer and engraver Adriaen Collaert (1560–1618).

A copy of Collaert’s Vita B. Virginis Teresiae a Iesu series was engraved in Rome in 1622 by the Dutch printmaker Johannes Eillarts (1568–1650). Known as Sanctissimae Matris Dei Marie de Monte Carmelo Beatae Teresiae (The Most Holy Mother of God Mary of Mount Carmel, the Blessed Teresa), Eillarts’ copy was detail-perfect, save for the fact that it was in reverse. This series by Eillart, not Collaert’s original, is likely the direct source for the St. Teresa paintings in the Convento de Santa Teresa. If this is true, these paintings are a Peruvian copy of an Italian copy of a Flemish engraving.

Underlining the complexity of the European and New Spanish print world, it is likely that the Convento Franciscano de la Recoleta paintings of de Vos’ series are also not based on the original engraving by de Vos. The most probable source for the prints is not Antwerp but Paris, where at least three engraved copies were produced by different engravers. Of these, the most closely related to the paintings seems to be ones published by Thomas de Leu in 1606.

Both of the convents’ paintings are part of the Cuzco School, a group of artists with an idiosyncratic and distinctive style that mixed Spanish Baroque elements with a visual vocabulary pioneered by those such as Tito Quispe. The Flemish references that appear in both sets of engravings remain intact in the paintings: the Mannerist figures, fantastical Italianate backgrounds, and Low Country riverside villages. But the paintings also introduce another world of ideas.

Though there are dozens of little changes, the most obvious, charming, and art-historically relevant are the birds in the Convento Franciscano de la Recoleta paintings. Peruvian birds are, in fact, a recognized attribute of the Cuzco School. The birds make these paintings as much Quispe Tito as de Vos. In one painting depicting St. Venerius, the artist added seven birds. In the painting of St. Hilarion, a colorful parrot sits with the praying saint. While St. Paternus turns his head toward empty space in de Vos and Leu’s engravings, in the painting that space is filled with a bird resembling a miniature ostrich.

While St. Paternus’ long-legged object of interest or St. Hilarion’s parrot seem to be such small details, they are, like the paintings themselves, evidence of a complex and interconnected system that allowed prints—and the ideas contained in them—to migrate.