Space Adventure: A Maltese Musical Fantasy For Children

Space Adventure: A Maltese Musical Fantasy for Children

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. On the theme of Music, Dr. Daniel K. Gullo has this story from the Malta collection.

Science Fiction and the 20th Century

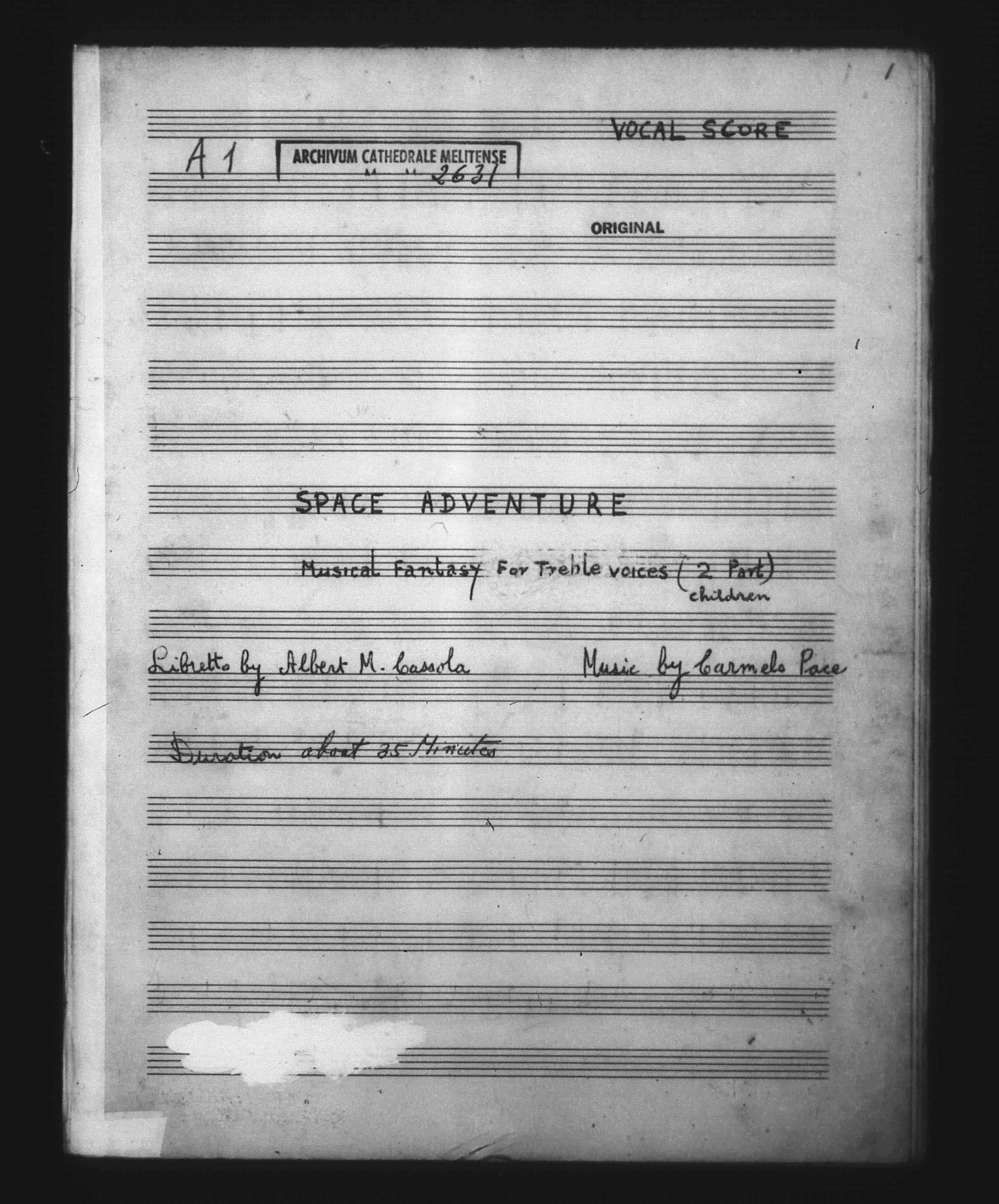

With their 1962 children’s musical Space Adventure, Carmelo Pace and Albert M. Cassola combined the fear and hope of space exploration with the genre of science fiction. To understand their work, we must first go back to a time not very long ago…

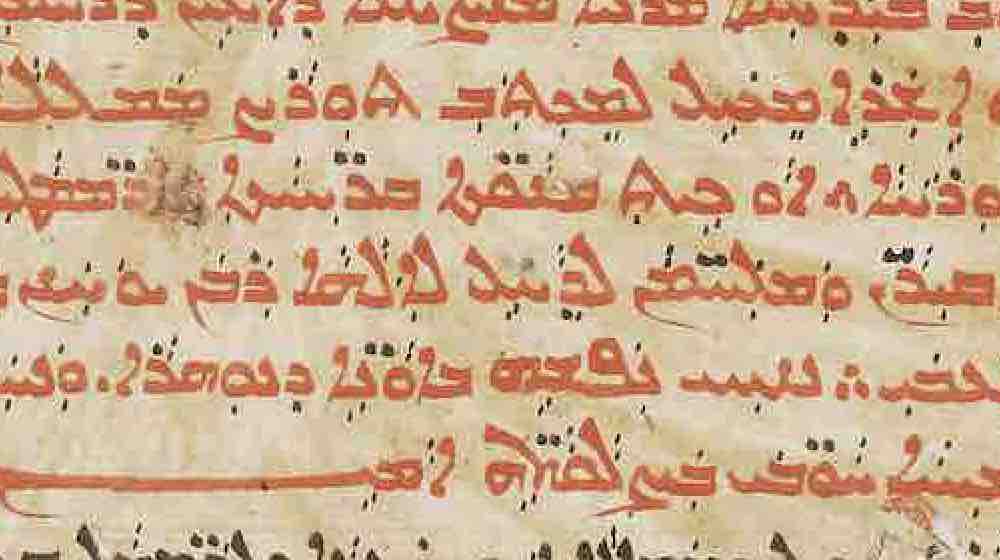

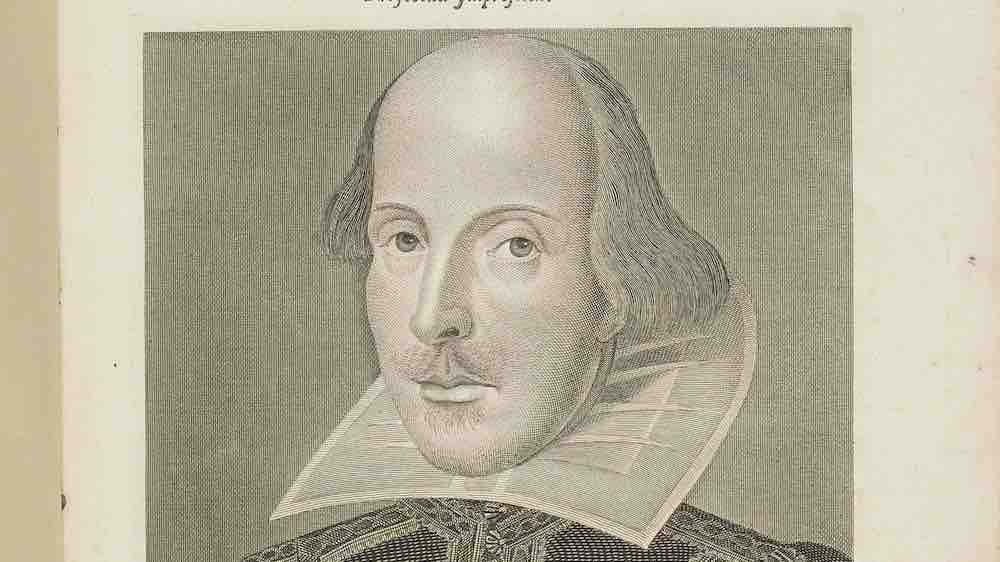

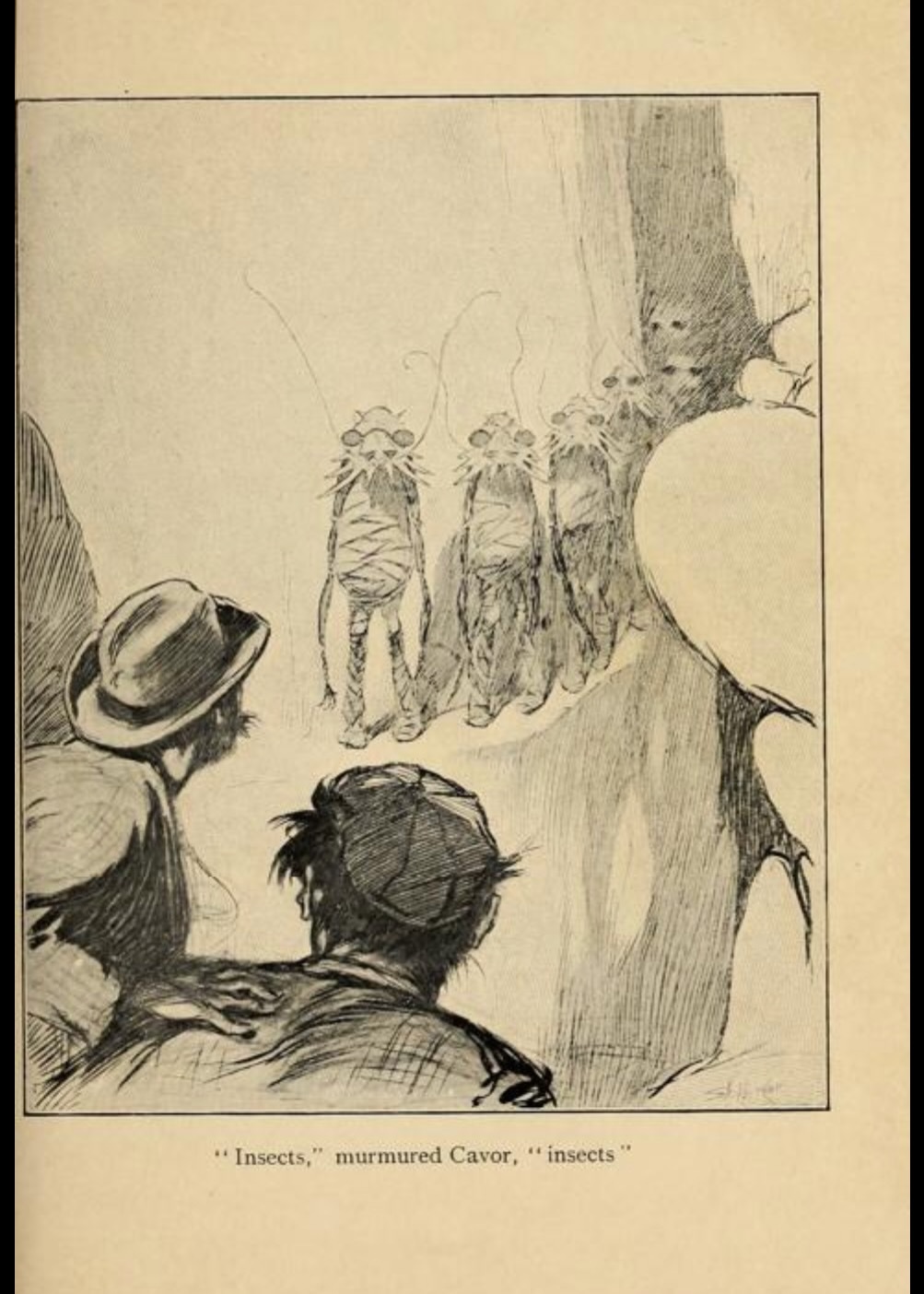

While writers and artists in previous centuries mused, moralized, and speculated about space and the existence of life on other worlds, the modern industrial revolution, aeronautical advancement, and the emergence of science fiction brought the imaginative pre-modern notions of space travel and extraterrestrial beings into the realm of scientific possibility. Herbert George Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898) entranced readers with the story of a Martian invasion of Earth. His The First Men in the Moon (1901) described how the Selinites from the moon end their communications with their first human contacts after the lunar beings realize humanity’s propensity to war. Drawing on Wells and Jules Verne (Voyages Extraordinaires), Georges Méliès visualized space travel and extraterrestrial encounters in his silent film A Trip to the Moon (1902), a film narrative ending with the imperial ambitions of exploration. Gustav Holsts’ orchestral suite The Planets (1914–1917) created a grand new atmosphere for contemplating the magnitude of the planets, moving from astrological characterizations to the astronomical movements of astral bodies in the solar system; the sounds of “Mars, Bringer of War” and “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” modernized music’s relationship with space and life outside of Earth.

From Adults’ Tales to Children’s Media

Changes to the genre of science fiction also entered into media created for children. The comic strips Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers brought a multi-media approach to a new generation of young audiences in the 1920s and 1930s, utilizing the advent of radio, the advancement from silent film to sound, and the serialization of comic books. The film serials King of the Rocket Men (1949) and Radar Men from the Moon (1952) continued the space adventure genre but modernized it with recent scientific advances in rocketry and jet propulsion developed in World War II.

The success of these early media formats triumphed with the invention of television and mass marketing. Media companies relaunched pre–World War II film serials as television series. New programs such as Captain Video and his Video Rangers (1949–1955) and Space Patrol (1950–1955) were created to fill the demand. Merchandise was sold to promote the television shows. Toys encouraged children to imagine futuristic space adventures: heroic escapades traditionally associated with knights, musketeers, and pirates were now enacted in a spaceship, on another planet, and with extraterrestrial beings, both frightening and wondrous.

Space Travel and Fiction Coming to Life

The imaginative period of the first half of the 20th century changed rapidly between 1957–1963, as the world of science fiction began to merge with the reality of scientific advancement. The successful Soviet launch of a satellite into Earth’s orbit with Sputnik 1 (1957) and the impact of the United States landing a spacecraft on the moon with Luna 2 (1959) brought human technology into space.

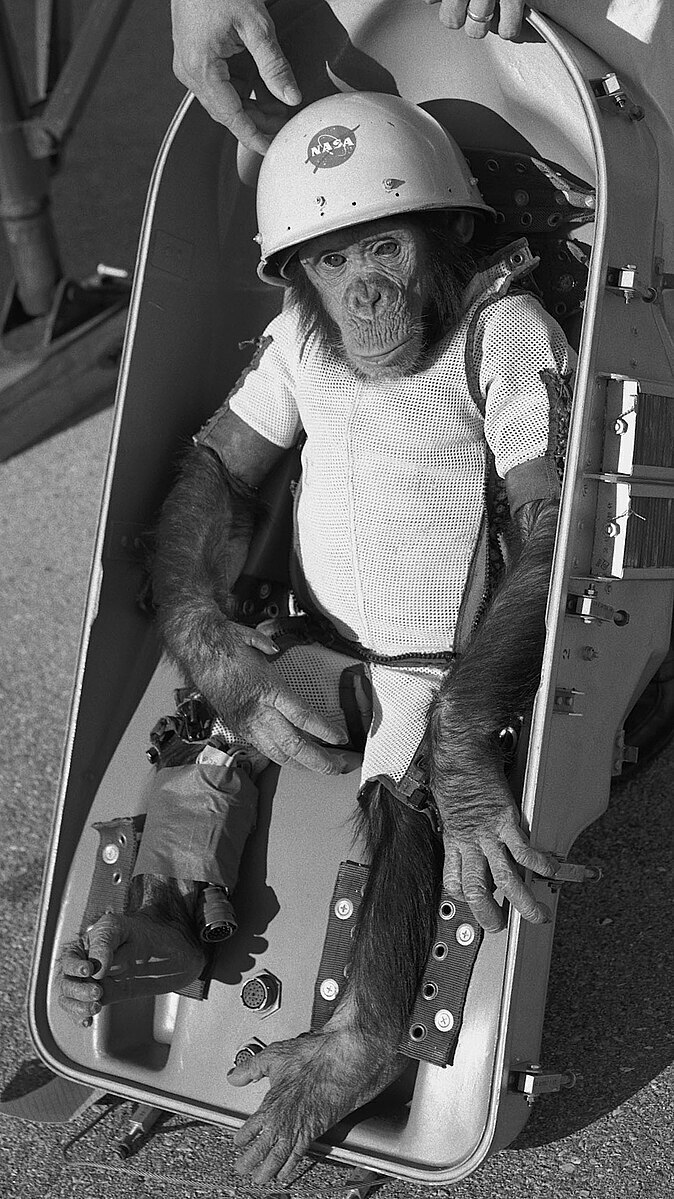

The mammalian flights of Sputnik 2 (1957), with the dog Laika, and the chimpanzee Ham on United States’ Mercury-Redstone 2 (1961), validated that earth creatures could travel into space and survive reentry to Earth, as in the case of Ham the Astrochimp.

In April 1961, the Soviet Cosmonaut Yurgi Gagarin’s orbit of the Earth in Vostok 1 brought humanity into and back from the stars, while a month later the American Alan Shepherd in Mercury-Redstone 3 demonstrated that one could execute navigational control of spacecraft, another step allowing for space travel. In 1963, the Cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman launched into space in Vostok 6, showing young women that they too could imagine themselves as part of the same space odyssey.

The focus on life beyond Earth carried with it new aspirations and marvels open to humanity. It also included the fears of a great war between superpowers involving space and nuclear weapons. This fear was only slightly diminished by the creation of the United Nations (1945) and the International Astronautical Federation (1951).

A Maltese Space Adventure

Pace and Cassola wrote Space Adventure in Malta in 1962, taking advantage of the fascination and fears of space travel one year after the first human flights into orbital space. The plot followed those typically found in the genre children’s science fiction serials as developed in the 1920s.

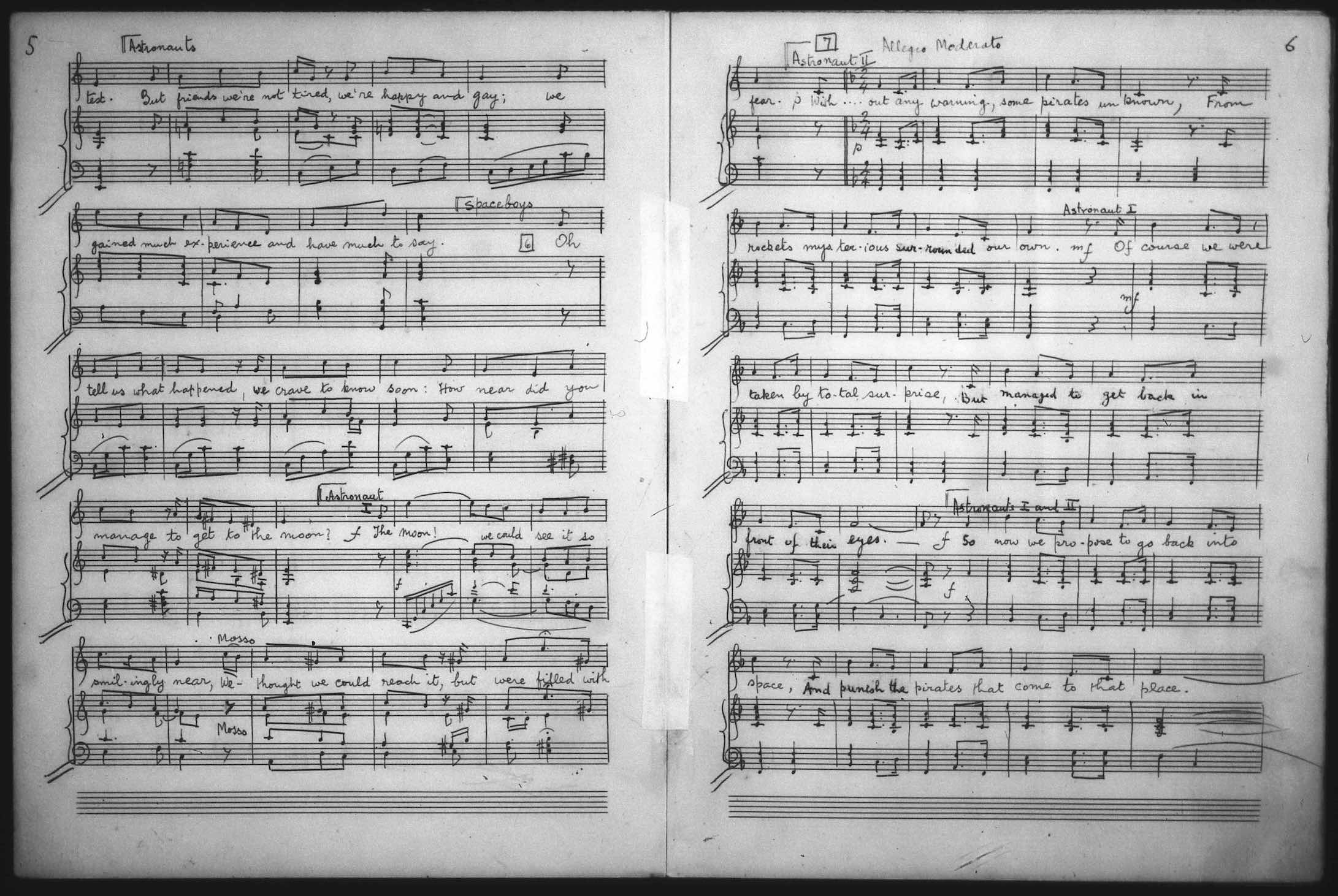

Spaceboys in training on Earth see a rocketship entering the atmosphere, which lands in the sea. The event causes the spaceboy astronauts to recount their marvelous journey to the moon, which was interrupted by what they believed to be space pirates in attack: “without any warning, some pirates unknown, from rockets mysterious surrounded our own.” Afraid of future attacks, the astronauts resolve to return to space to defeat the pirates by using a special electroparalysis ray.

A chorus of ground-staff boys communicate the subsequent events in space, singing how the astronauts have now encountered boys and girls from Venus, who were earlier mistaken for pirates. The ground staff calls on the girls of planet Earth to prepare a welcome with dance and song. When both groups return to Earth, the Venus boys and girls proclaim their interest in peace and the Earthlings reflect: “you see whom we first thought were foes, know nothing of anger and much less of blows.” The two groups sing a dialogue about play, happiness, and their desire to dance and enjoy youth. The girls from Venus and Earth exchange gifts, while the Earth girls ask the boys for “frocks and bangles and bracelets and stockings.” Interludes of dancing break up the dialogue, realizing the mutual desire to live and play.

Despite the frivolity of the musical, Pace and Cassola’s Space Adventure responded to Cold War fears within the context of Maltese Catholic youth education: terrors of the war dissipate only through love and faith. Though the Venusians are alien, the triumph of peace in this musical emerges from their mutual belief in monotheism, as well as their youth.

“Those that want trouble better beware,

This world is too splendid to finish in smoke.

We want to be able to play, laugh and joke.

If we can’t make round us a Universe gay,

we’re wasting our time if for Heaven we pray.

There’s only one Being who is above all:

the time has arrived now to answer his call.

The worlds in the cosmos must quickly unite,

and never indulge in a war or fight…

Although our two worlds are so very apart,

the bonds that now bind us are those of the heart.

That’s our idea; then all we confide

in One Supreme Being by whom we’ll abide.”(Malta Series I 8093, pages 10–12)

Space Adventure premiered on January 4, 1964, at the Catholic Institute of Malta in Floriana, with Frank Ganado as director and Father Michael D’Amato as conductor. Costuming was designed by the Malta Society of Arts, Manufacturers & Commerce. Concert versions with a choir were performed that same year on February 17 and May 14, with arrangements made for marionettes. The musical was not performed again for over a decade, when Helen De Gabriele directed a performance at Salesian Hall, Stella Maris College, in Sliema, Malta, on April 14, 1977.

Between these performance dates, Malta achieved independence from Great Britain (1964), two tortoises on the Soviet Zond 5 circumnavigated the Moon (1968), and humanity landed and walked on the Moon for the first time with arrival of the Eagle module from the United States in July 1969. Science fiction also returned to its roots when Star Trek, first broadcast on television from 1966 to 1969, remade science fiction into an adult genre. Despite these changes, Pace’s and Casolla’s vision of space, dance, and music did not disappear. David Bowie’s song “Starman,” performed as Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in 1972, recalls Pace’s and Cassola’s emphasis on the importance of dance, joy, and youth in the meeting of humanity and beings from outer space:

“There’s a starman waiting in the sky

He’d like to come and meet us

But he thinks he’d blow our minds

There’s a starman waiting in the sky

He’s told us not to blow it

‘Cause he knows it’s all worthwhile

He told me

“Let the children lose it

Let the children use it

Let all the children boogie”(David Bowie, Starman, 1972.)