Woven Worlds: Patterns In Textiles, Manuscripts, And Monuments In Armenian Visual And Material Culture

Woven Worlds: Patterns in Textiles, Manuscripts, and Monuments in Armenian Visual and Material Culture

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Dr. Ani Shahinian has this story about Textiles.

Armenian visual culture is represented in diverse materials that carry pattern and memory: stone, metal, wood, fiber, textile, pigment, parchment, and paper do not merely function as passive supports, but as part of an active ensemble of materials in the hand of an artist who weaves together the work of narrative and meaning-making.

For example, when we look closely at Armenian manuscripts alongside Armenian textiles—such as carpets, embroideries, needlelace, and woven cloth—we begin to see a shared visual and material grammar governing pattern and form. Patterns and design move from one medium to another as the techniques of craftsmanship in each medium adapt to specific materials, traditions, and trade networks. Surfaces become sites where piety, economy, and identity are worked and woven into discernable patterns to communicate meaning and beauty.

Considering Armenian manuscripts and Armenian textiles together—especially the use of cloth in manuscript bindings and the recurrence of ornamental patterns across textile and paper—we are invited to move beyond the divisions of “fine art” and “craft.” Instead, Armenian material culture is a set of interdependent practices shaped by shared techniques, visual vocabularies, and embodied ways of making, seeing, and touching—enhancing one’s imagination.

Fabric at the Heart of the Book: Doublures and Lining Textiles

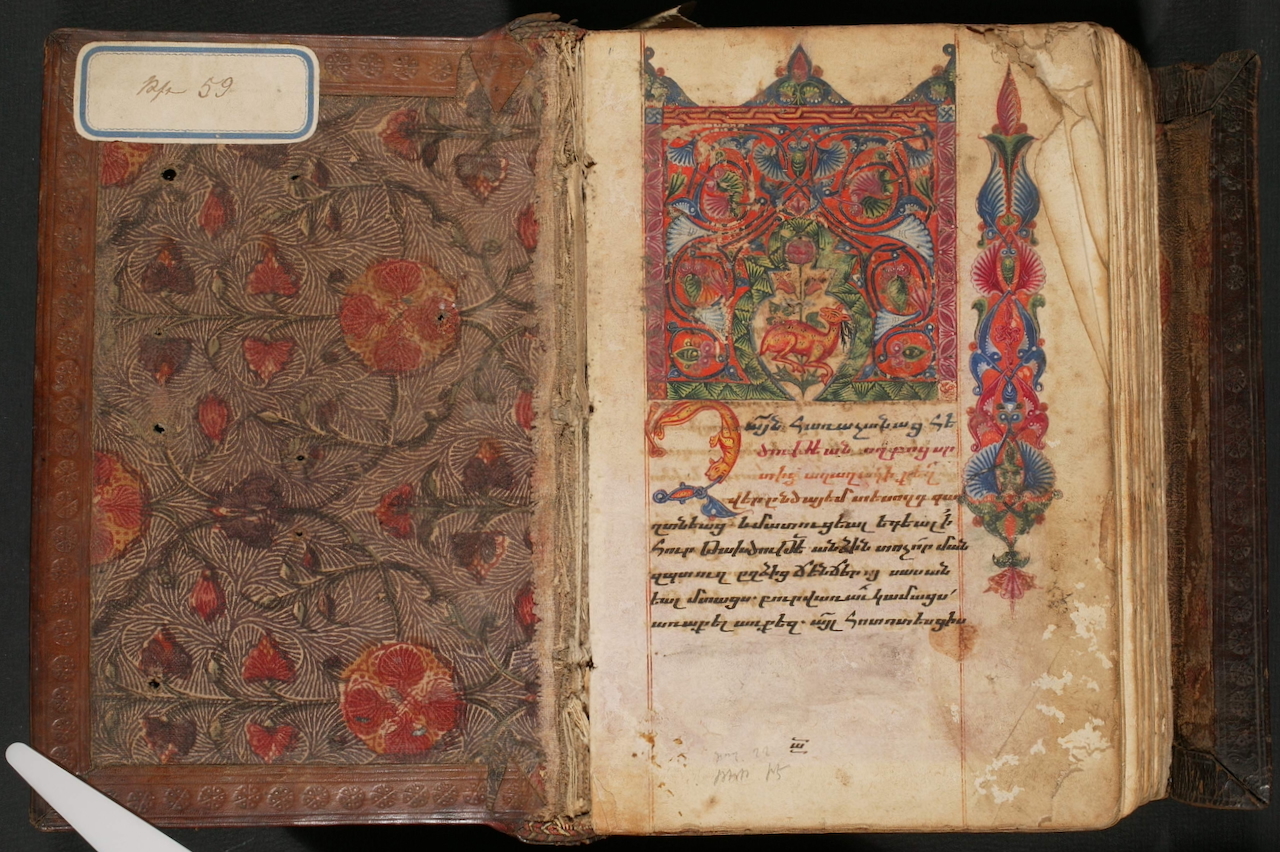

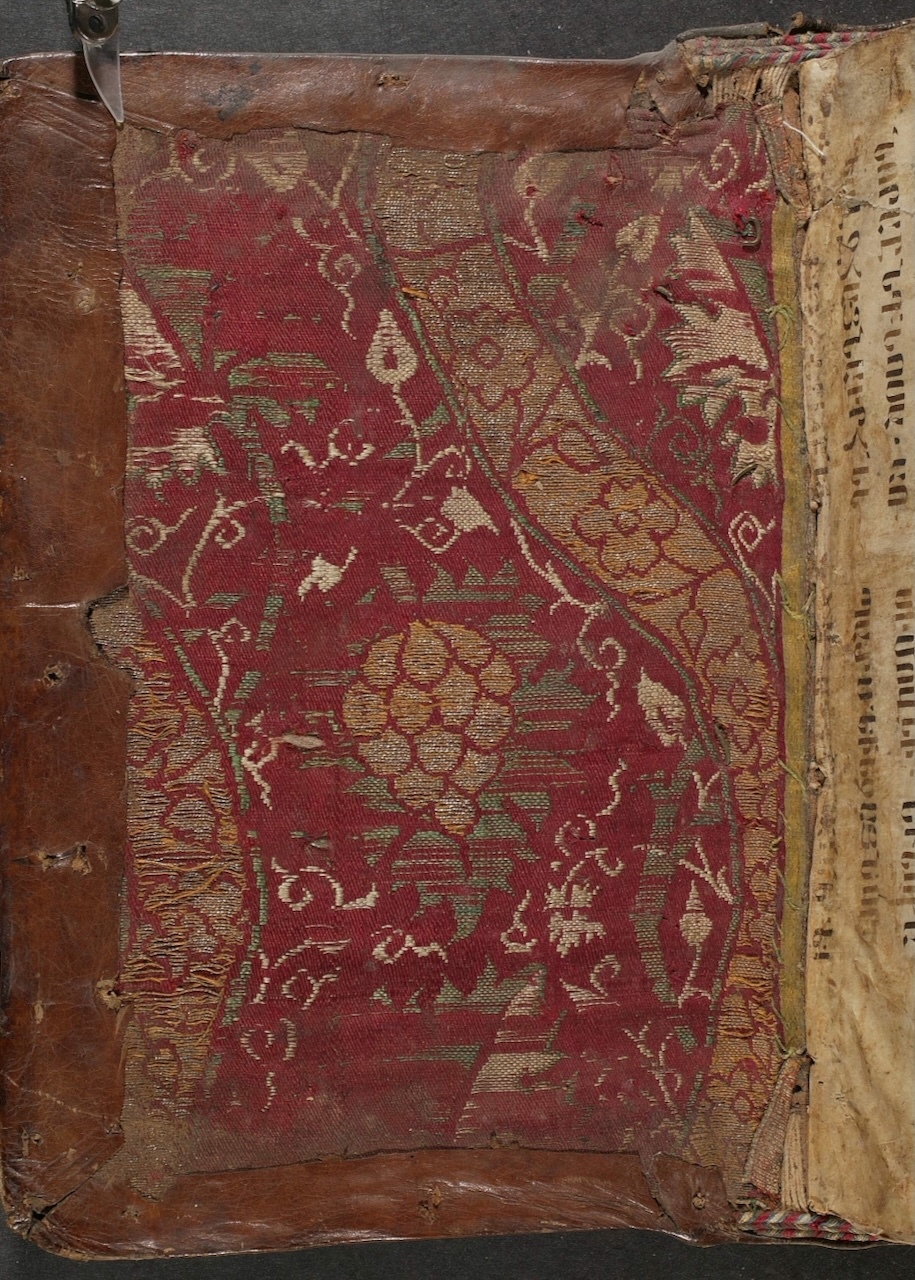

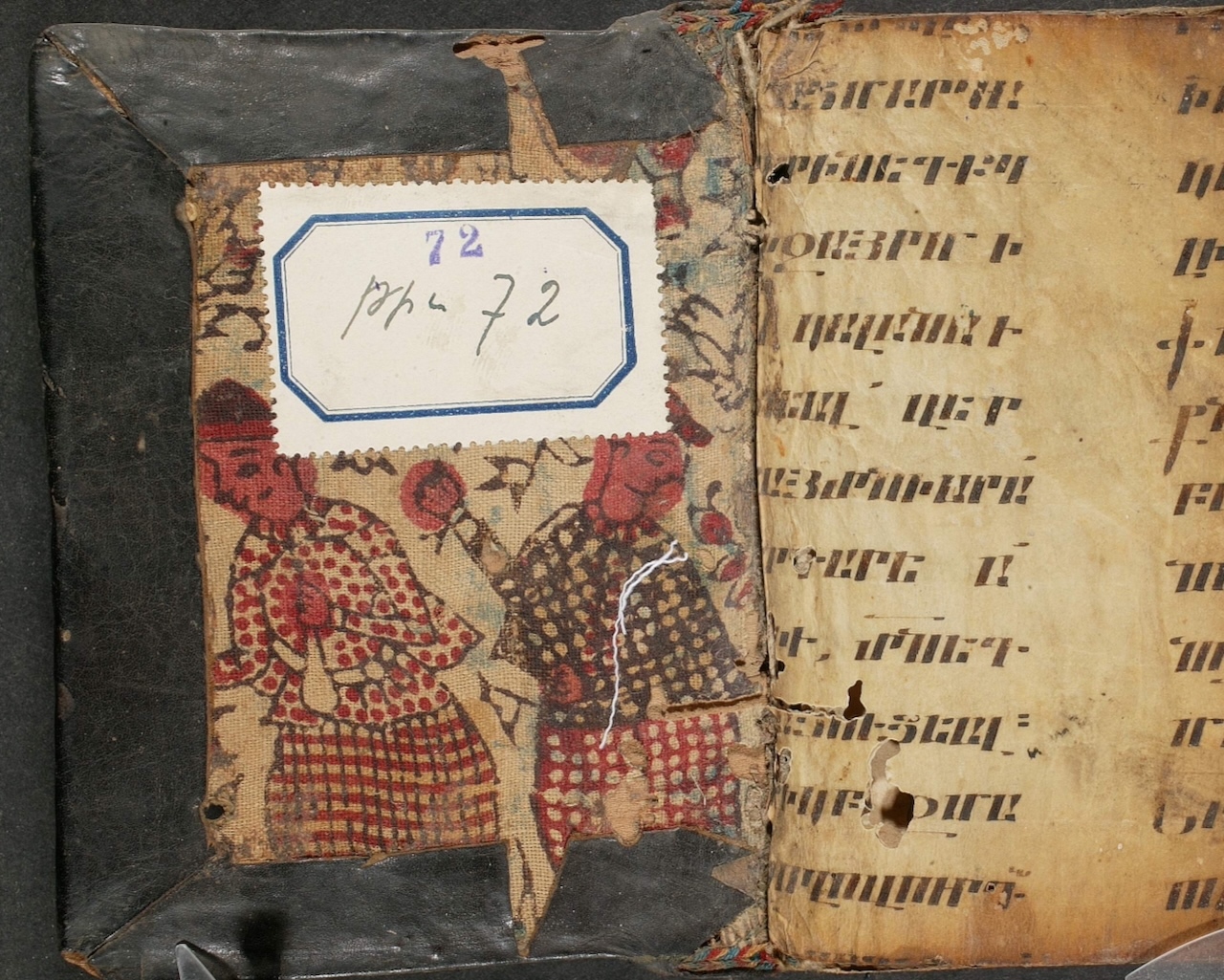

A reader of this Armenian prayer book from 18th-century Constantinople (APIA 00124) is instantly brought into the conversation between artists of textile, text illumination, and bookmaking. The inside cover is lined with a finely-printed floral textile sewn over the wooden board. The textile features an encompassing pattern of large red rosettes and smaller floral motifs linked by scrolling stems and stylized leaves, set against a darker background. Carefully fitted to the interior of the binding, the cloth speaks to the close relationship between textile design, bookmaking, and ornamental traditions in Ottoman-era Armenian material culture.

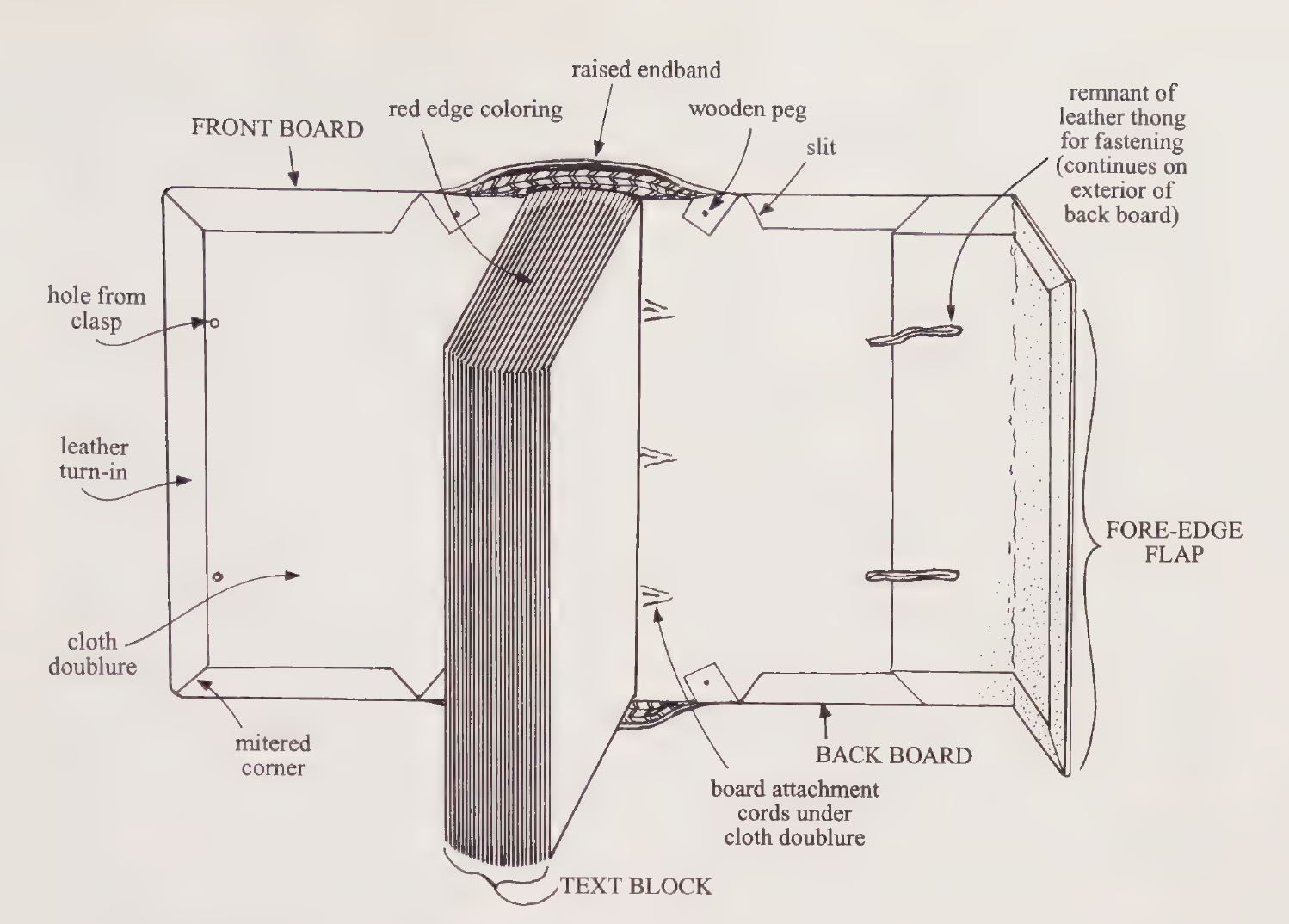

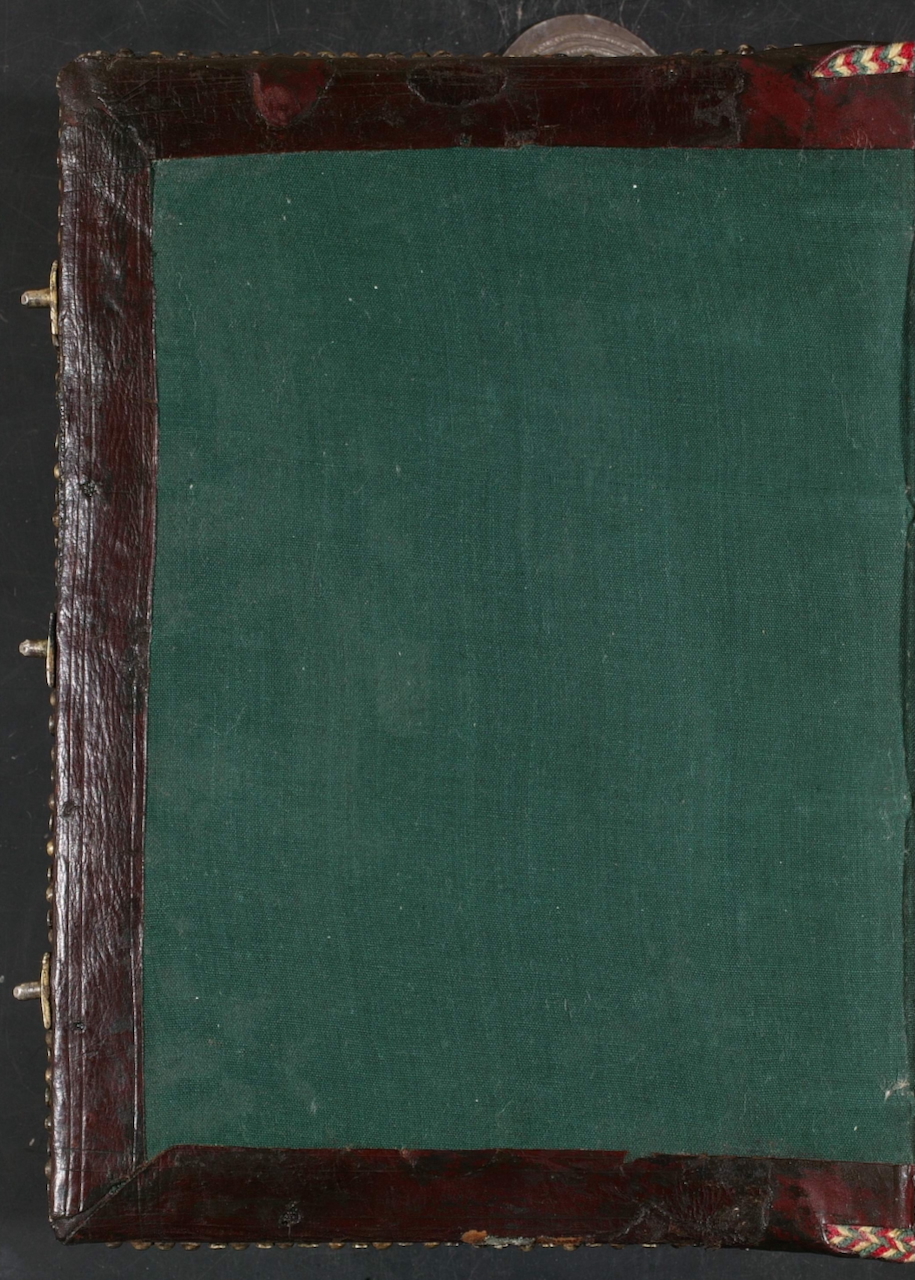

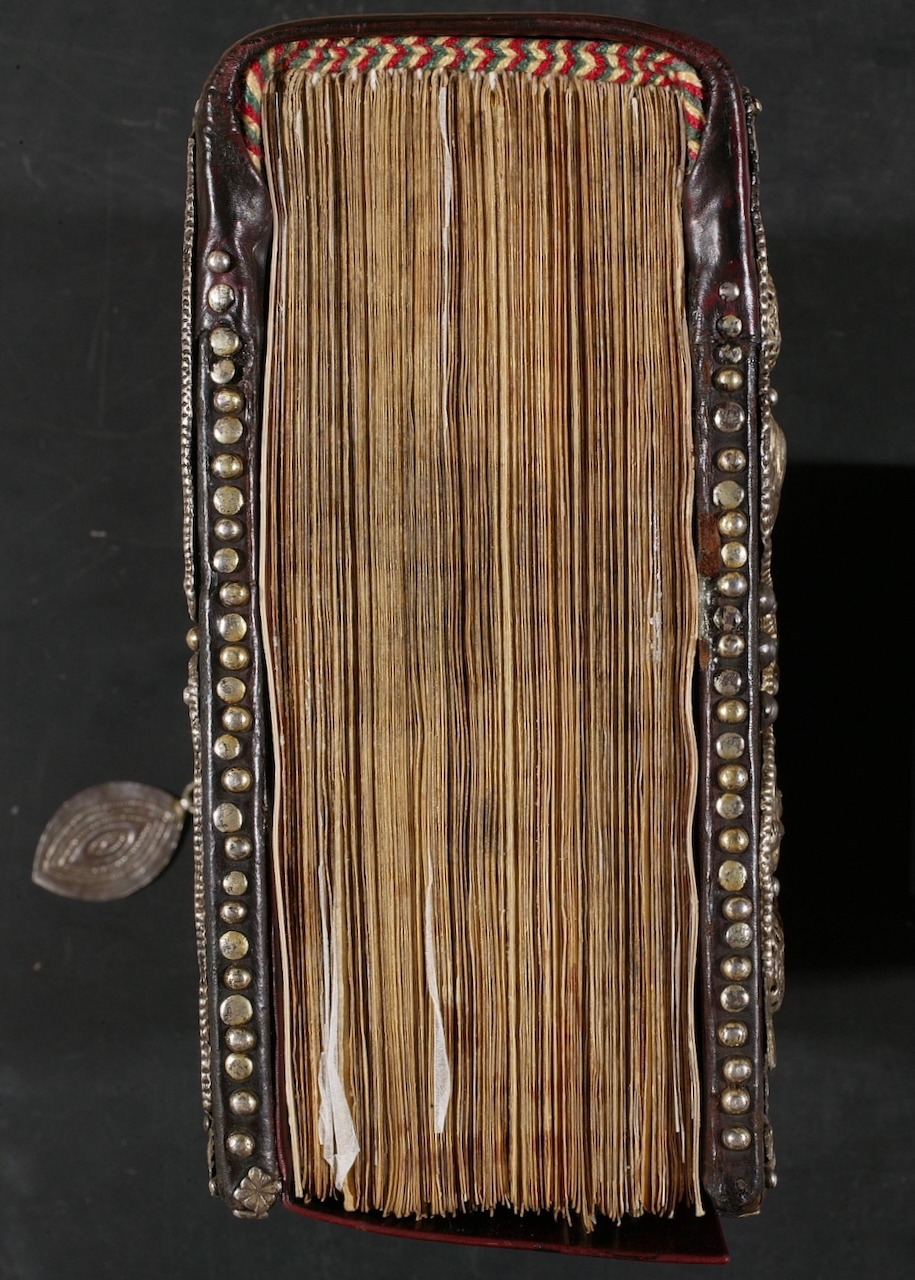

Armenian manuscript binding practices preserve a layered history of material and technique. Typically, after the text block was sewn together and the wooden boards attached, skilled bookbinders lined the inside of the boards with cloth, fully covering the wood as well as the cord attachments. This interior lining—often referred to as a cloth doublure—could range from plain cotton or linen to, in more luxurious bookbinding, silk brocade. Far from being incidental, this layering of textile over wooden boards is structurally essential and artistically intentional.

The cloth doublure performs several roles. It protects the manuscript pages, stabilizes the binding, and conceals the wooden boards. At the same time, it introduces color, pattern, and tactility into the interior space of the book. The moment a reader opens an Armenian manuscript, they encounter cloth before text—a threshold that mediates between the exterior leather binding and the sacred words within. The cloth doublure inside a manuscript binding may seem modest compared to a monumental khachkar (cross stone) or a richly illuminated Gospel page. Yet it belongs to the same world. It carries memory of labor, devotion, technique, tradition, and aesthetic judgment.

Furthermore, these textiles serve as historical record of trade networks. Linen and cotton suggest local production and everyday utility, while silk brocades point to trade routes connecting Armenian communities to Persia, India, and China—beyond the Ottoman world. The doublure thus becomes a small but eloquent witness to Armenian participation in broader networks of material and cultural exchange.

Patterns Without Borders: From Needlelace to Khachkars

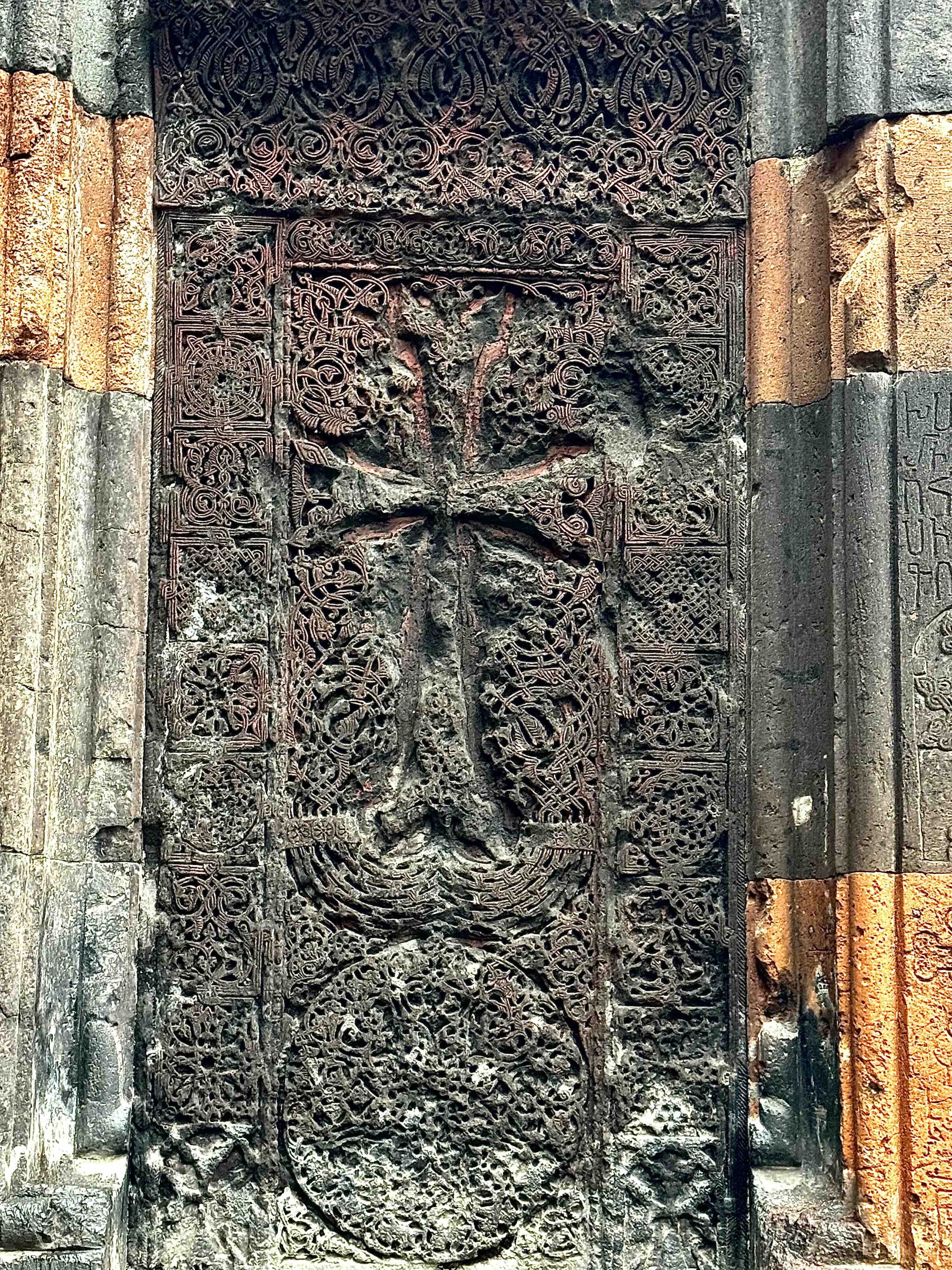

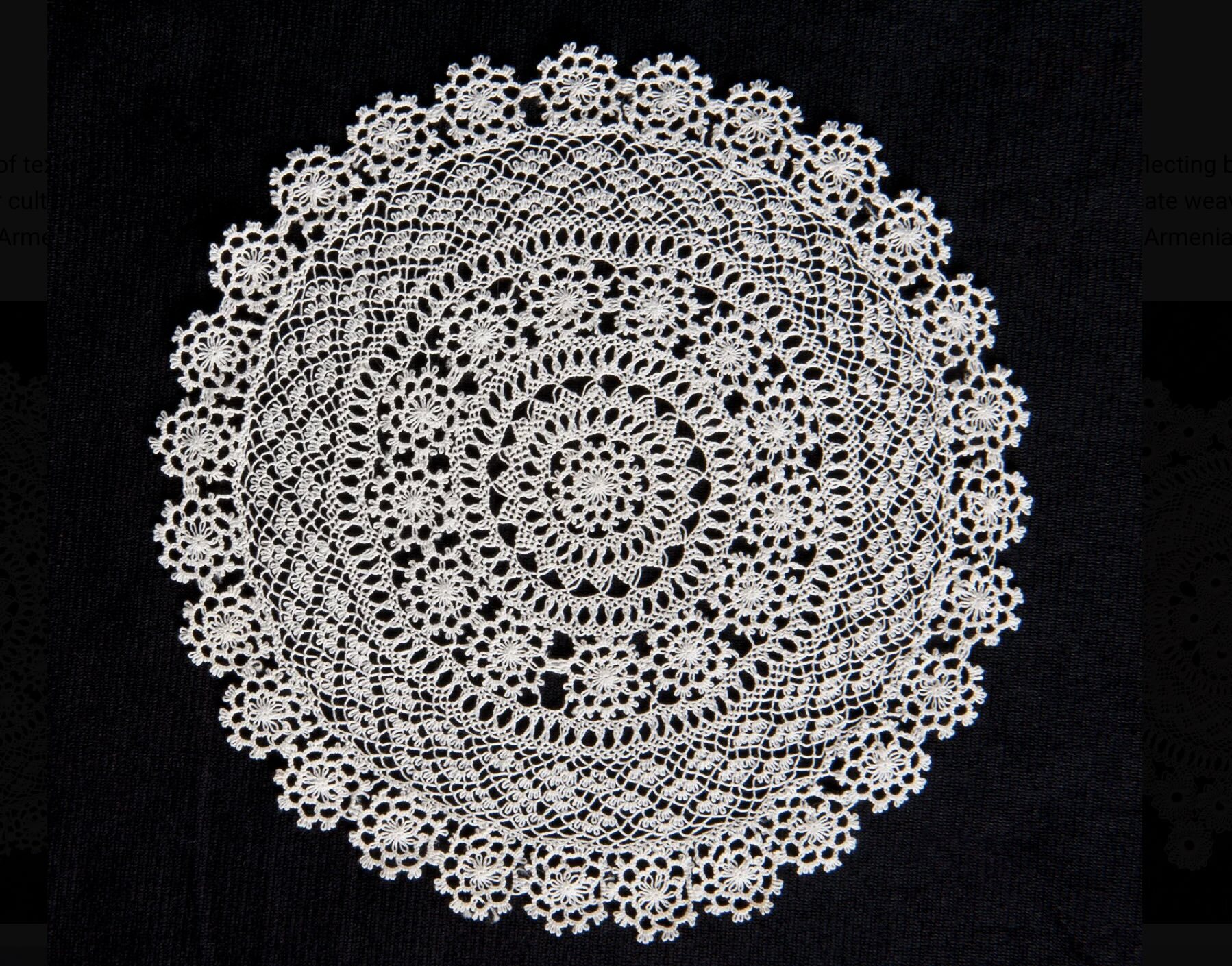

The weaving of intricate patterns creating beauty and meaning is not limited to books. Armenian needlelace doilies—an especially refined form of handwork—display geometric floral motifs that are strikingly similar to those carved into khachkars (cross stones). Rosettes, interlace, radiating crosses, and repeating knots appear in thread and stone alike. The scale and medium differ, but the underlying visual logic remains connected to a shared cultural language.

This repetition suggests more than aesthetic preference. In khachkars, patterns are incised into tuff stone, producing depth through shadow and relief. In needlelace, the same logic is translated into tension, void, and knot. One material resists; the other yields. Yet both require disciplined repetition, skilled hands, and an attentiveness to negative space. Both reflect a shared conceptualization of order, rhythm, and geometric pattern.

Seen in this lineage, Armenian textiles do not merely decorate domestic or liturgical life; they participate in the same symbolic language that shapes monuments and manuscripts. Pattern recognition is a language that moves freely across mediums—stone, cloth, parchment—and even transcends space and time.

Illuminations of Textiles

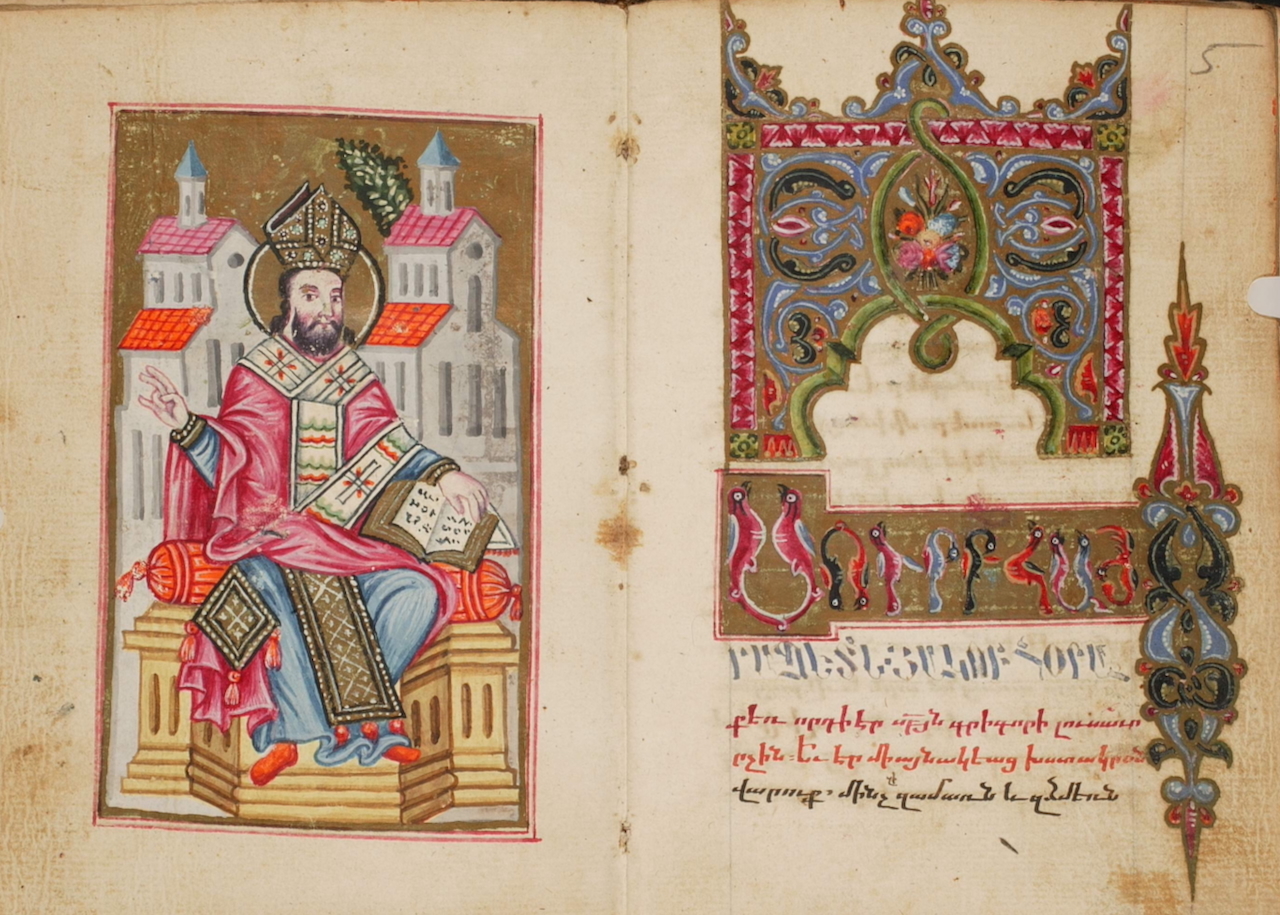

Manuscripts also figuratively depict textiles, and Armenian illuminations are rich with representations of clothing—simple and ornate, earthly and heavenly.

Garments are patterned, layered, and color-coded, drawing on contemporary textiles while also articulating theological meaning. Liturgical vestments are especially revealing in this way. The omophorion worn by bishops, for example, often appears patterned, edged, or marked with crosses, signaling both ecclesiastical authority and continuity with specific traditions of weaving and embroidery. Depictions of saints’ garments similarly balance historical customs and colors association to their saintly lives; martyrs may be clothed simply and in red, prophets in layered robes, hierarchs in textiles that signify their status as bishop or patriarch.

Even angelic garb participates in this linguistic system. Angels are frequently clothed in luminous fabrics that defy gravity—flowing, patterned, and often outlined with gold. Textile pattern here becomes a bridge between the visible and invisible worlds.

Weaving Together: Thread and Text

When Armenian manuscripts and textiles are considered together, a more integrated vision of Armenian material culture comes into focus. Carpets, tablecloths, curtains, needlelace, stone carvings, paintings, and illuminated books all participate in a shared continuum of pattern-making. Motifs recur not out of habit alone, but because they are meaningful, durable, and capable of adaptation across scale, medium, and use—potent carriers of memory and identity.

Further Reading:

Sylvie L Merian, "The Characteristics of Armenian Medieval Bindings," in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 10; Proceedings of the tenth international seminar held at the University of Copenhagen 19th-20th October 2006 (Copenhagen, DK: Museum Tusculanum Press, Univ. of Copenhagen, 2008): pp. 89–107.

Jenny Hille & Sylvie L. Merian, 2011. "The Armenian Endband: History and Technique." The New Bookbinder 31: 45–59.

T. F. Mathews and R. S. Wieck, 1994. Treasures in heaven: Armenian illuminated manuscripts. New York: Princeton, New Jersey: Pierpont Morgan Library.

Armenian Rugs Society (Ed.). 2014. Armenian rugs and textiles: An overview of examples from four centuries.

Textiles in the collection of the Armenian Museum of America, Watertown, Massachusetts.

Dr. Patricia Engel, principal investigator for the project Textiles in Armenian Manuscripts and Printed Books at the University for Continuing Education Krems, Austria.

Moreton, Melissa and Akbari, Suzanne Conklin. Textiles in Manuscripts: A Local and Global History of the Book, dG Arts, 2026.