Anna Roede And The Fight For Sovereignty

Anna Roede and the Fight for Sovereignty

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Western European collection, Dr. Jennifer Carnell has this story about Women.

When Martin Luther proclaimed his 95 Theses in 1517, the resulting shockwaves of the Reformation created shifts in the balance of power and rearranged regional identities and loyalties throughout the states that now make up modern Germany. After upholding Western Christian traditions that spanned centuries, monastic communities were faced with the unprecedented decision to adopt these new teachings or hold fast to their old way of life. Some knights and lords saw an opportunity to confiscate the property of monasteries in the process of secularization, which often lead to the permanent loss of the communities’ books and records.

In the midst of this upheaval, a monastic clerk named Anna Roede found herself using her ability as a scribe and recordkeeper to assert her community’s authority and identity, which were threatened by the new bids for power.

Anna was a young woman when, just before the Reformation began, she joined the Benedictine monastery of Kloster Herzebrock, located in the region of Rheda, found today in northwestern Germany. Anna came from a bourgeois family in Münster that had connections to the monastery—her mother’s brother had a high position as a financial administrator there, and her parents and brother contributed donations to the monastery. Around 1520, Anna took over the monastery’s scribal office of rent clerk.

The ruler of her region, Count Konrad von Tecklenburg, was the first to convert the area to Lutheranism in an attempt to solidify his borders, which were contested by the Bishop of Osnabrück. In 1532, the Count began attacking Kloster Herzebrock by military and diplomatic force, perhaps hoping to secularize the community and claim financial jurisdiction over the parish. Anna’s uncle aided the monastery’s abbess in managing the difficult financial situation, and Anna worked under him.

The divisions rocking the powers in Anna’s monastic world also found their way into her family. The Anabaptist movement came to Münster that same year, and Anna’s father supported the radical Protestant group as they forcefully overthrew both Catholic and Lutheran leadership and established a brief theocracy. The movement was quelled by the newly elected bishop of Osnabrück, Franz von Waldeck, and Anna’s father lost his life in the turmoil. Marauding troops raided Kloster Herzebrock for food, placing further financial strain on the monastery.

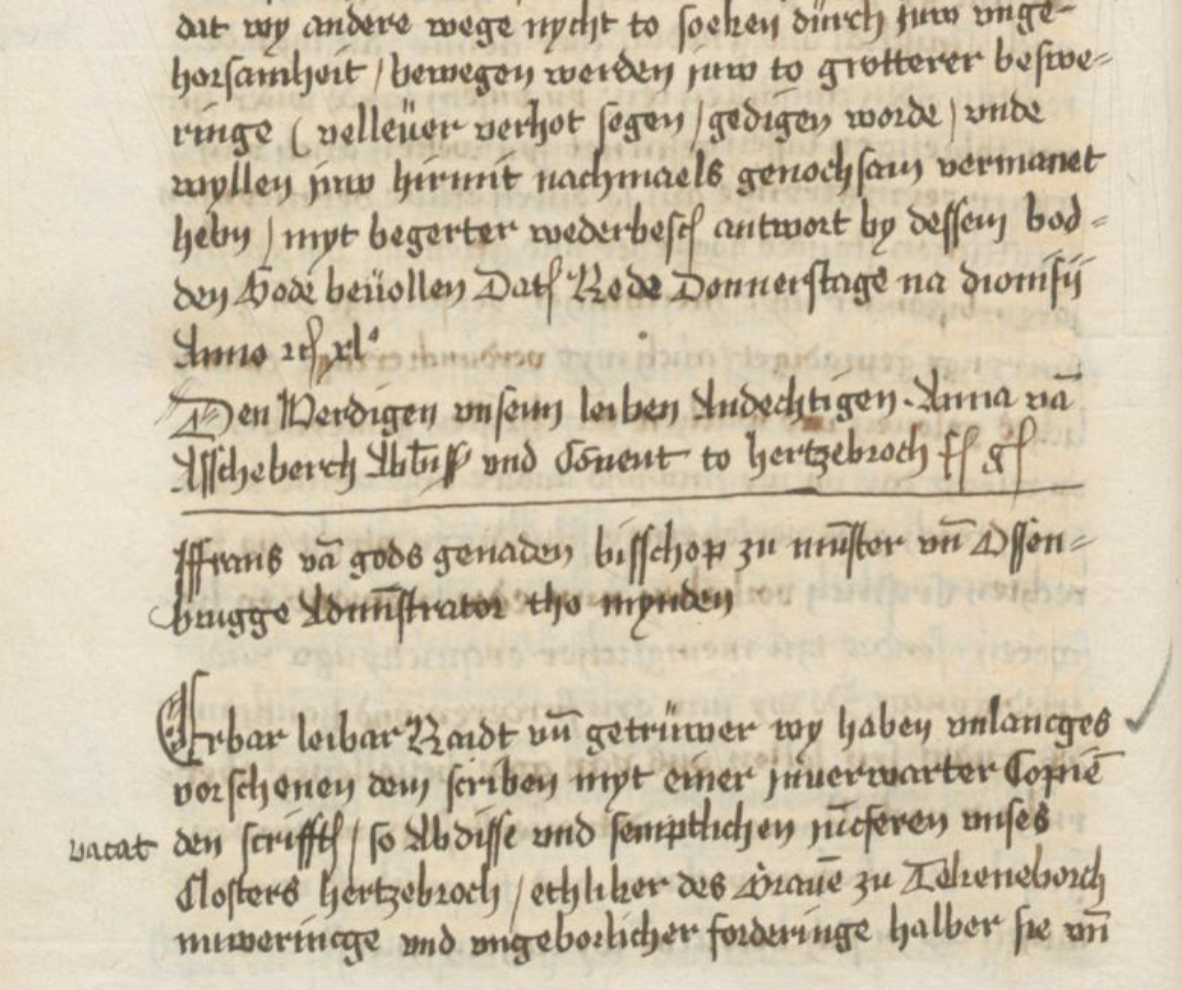

The struggles with Count Konrad continued into the next decade. As bishop, Franz von Waldeck had a vested interest in keeping the monasteries free from the Count’s attempts to overtake them. However, the Bishop also had conflicting loyalties—he himself was sympathetic to the Reformation, though he could not be open about it—and he attempted to reform Kloster Herzebrock and her neighboring monasteries.

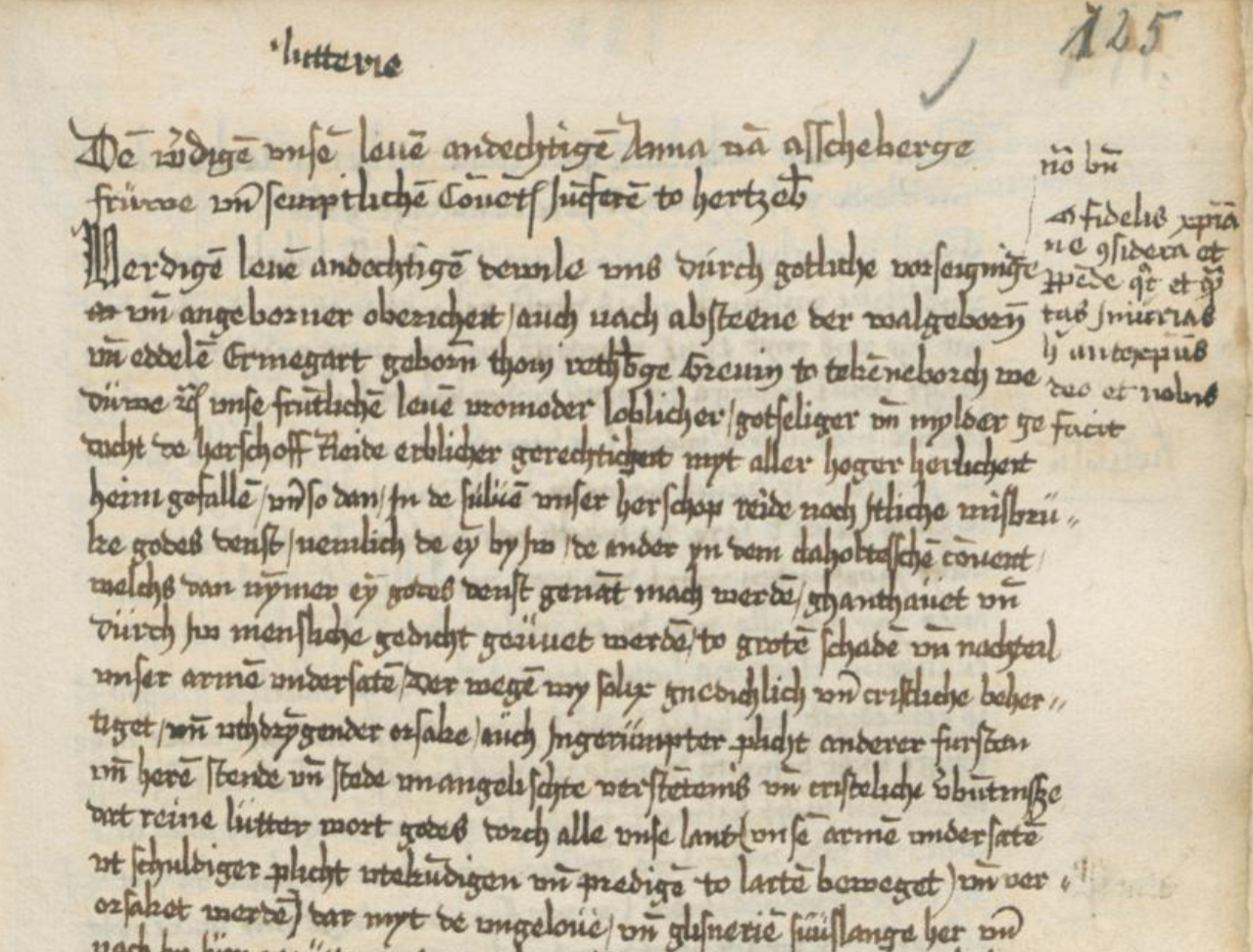

The abbess of Kloster Herzebrock, Anna von Ascheberg, faced pressure on both sides—political and religious—to conform. The Abbess staunchly resisted.

When Anna Roede’s uncle died in 1545, she continued to manage the monastery’s finances. Three years later, Kloster Herzebrock initiated a trial against Count Konrad.

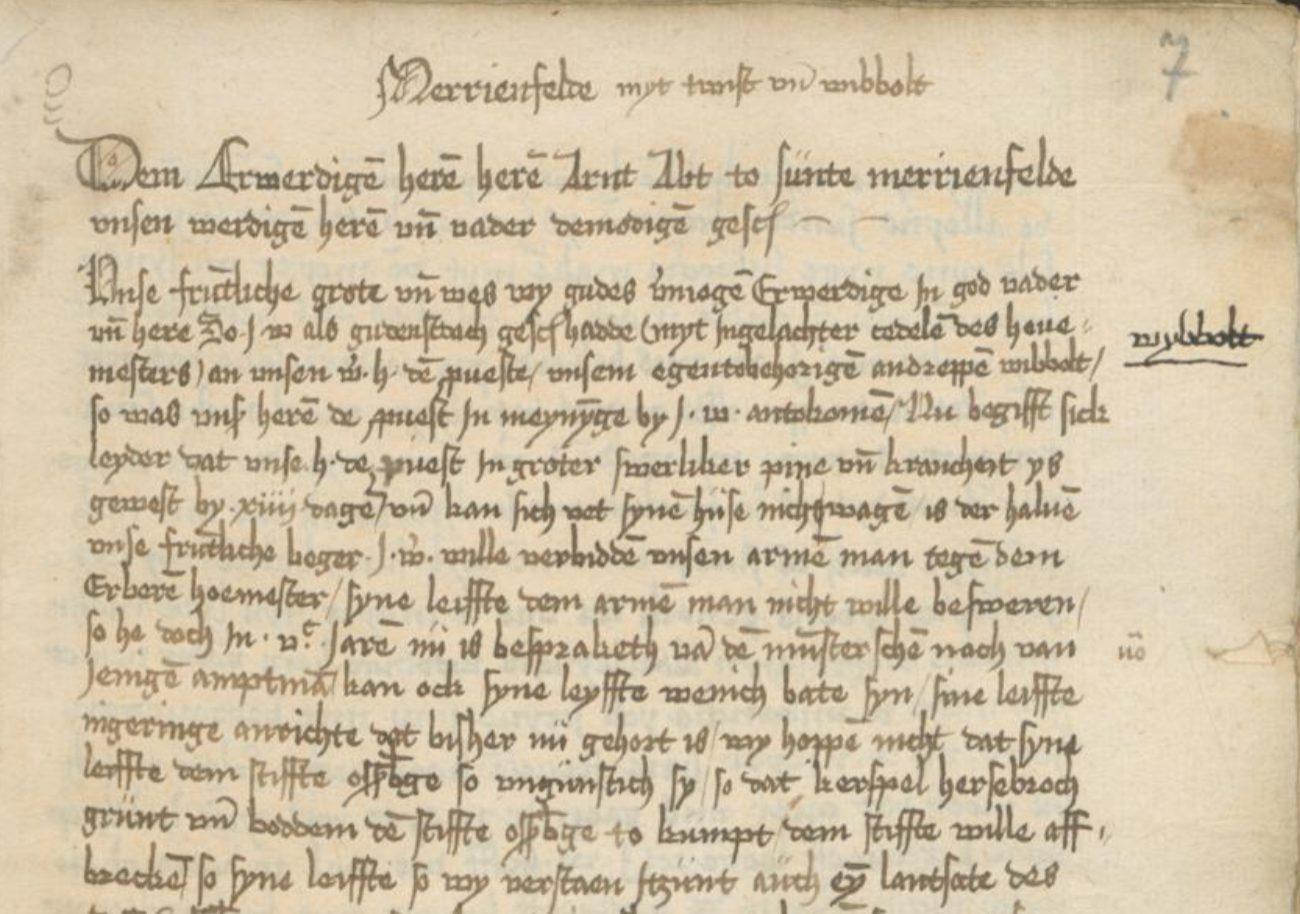

Around this time, Anna made handwritten copies of 36 of her abbess’s letters and supplemented them with contextual explanations. Anna added two chronicles documenting the history of the monastery—particularly covering the tumultuous 1530s—and, together with the letters, formed what scholars call a cartulary, which asserted the monastery’s claim to its property. With such documentation, Anna was helping the monastery fight for its existence.

This cartulary—found in HMML’s collections as HMML 41034, a microfilm of the manuscript housed at Nordrhein-Westfälisches Staatsarchiv Münster —is only one in a series of cartularies that Anna copied which were used in the ongoing legal disputes.

The cartulary’s two chronicles were Anna Roede’s own creation, drawing inspiration from oral tradition, legal documents, and existing chronicles such as Ertwin Ertman’s 15th-century “Chronicle of the bishops of Osnabrück”. Although she knew Latin, Anna made her histories accessible by using the more widely spoken German, perhaps for the benefit of her fellow nuns and so that other sympathetic ears might be reminded of Kloster Herzebrock’s role in the region.

The motivation to write a history of her community, while helping with the immediate concern of the Count’s encroachment, was also a reflection of a broader impulse in her monastic order. A century earlier, the monastery had joined the Bursfeld Congregation, a movement within the Benedictine Order that had encouraged its adherents to draft their own histories.

The 1550s saw a changeover in the players of the story: Count Konrad died, and his daughter took over the campaign to claim to sovereignty in the region. Johann IV von Hoya was now bishop, and the Church and government engaged in a bloody conflict that resolved only in 1564, a year after Abbess Anna von Ascheberg died. According to the treaty, the region was parceled up politically and spiritually, but Kloster Herzebrock was able to retain its property and its choice of confession.

In 1578, Anna Roede died within the community she helped to protect. It is remarkable that, at a time when most people lived and died without leaving a record of themselves, Anna was able to preserve a record not only of her monastery’s fight to exist but also of her own existence. Today, there is a common misconception that women in the Middle Ages and early modern period were not educated enough to be scribes. Anna’s work is a testament to the agency and knowledge of women who were asserting their presence and way of life amid the powerful forces shaping their region.

Further Reading:

Edeltraud Klueting, Das Kanonissenstift und Benediktinerinnenkloster Herzebrock. Germania sacra, N.F. 21: Die Bistümer der Kirchenprovinz Köln (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1986).