English Renaissance

Shakespeare’s Second Folio and the English Renaissance

“He was not of an age, but for all time!”

The English Renaissance (c. 1520—c.1650) was a time of cultural revival, religious turmoil, and the birth of what we today think of as English poetry. Unlike its Italian counterpart, visual arts were less significant in England at this time, as the literary arts and theater flourished.

Advances in printing, growing literacy rates, and London’s surging population developing into the largest city in Europe meant an eager and growing market for books and the written word. The English language rose to a place of international prestige and began to emerge across a wide variety of genres and geographies. Medieval religious plays, ballads, hymns, popular songs, classical translations, and contemporary literature converged in sixteenth-century England to create an atmosphere ripe for innovation. This was the world into which William Shakespeare emerged.

William Shakespeare and His Sources

William Shakespeare (1564–1616) is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the English language. His 38 plays, over 150 sonnets, and other writings continue to be performed, recited, published, translated and studied more than any other writer in English history. Despite the continued proliferation of his works today, Shakespeare never lived to see a collective edition of his plays printed.

Seven years after his death, John Heminges and Henry Condell, two fellow actors and contemporaries of Shakespeare, collected 36 of his plays and published them in folio format, a prestigious printing layout in which single sheets are folded in half and printed as four pages. This definitive printing, known collectively as the First Folio, is one of the most significant books ever published, and only about 235 editions still exist today held in collections all over the world.

Due to popular demand, a second edition was printed in 1632, known as the Second Folio, approximately 1000 copies were published, and one of the fewer than 200 surviving copies is part of HMML’s permanent collections. Almost 1,700 changes were made between the First and Second Folio, and it is thanks to this edition that most modern productions of Shakespeare are derived. As the English poet, Ben Jonson exclaimed in his commendatory poem at the front of the Second Folio “he was not of an age, but for all time!”

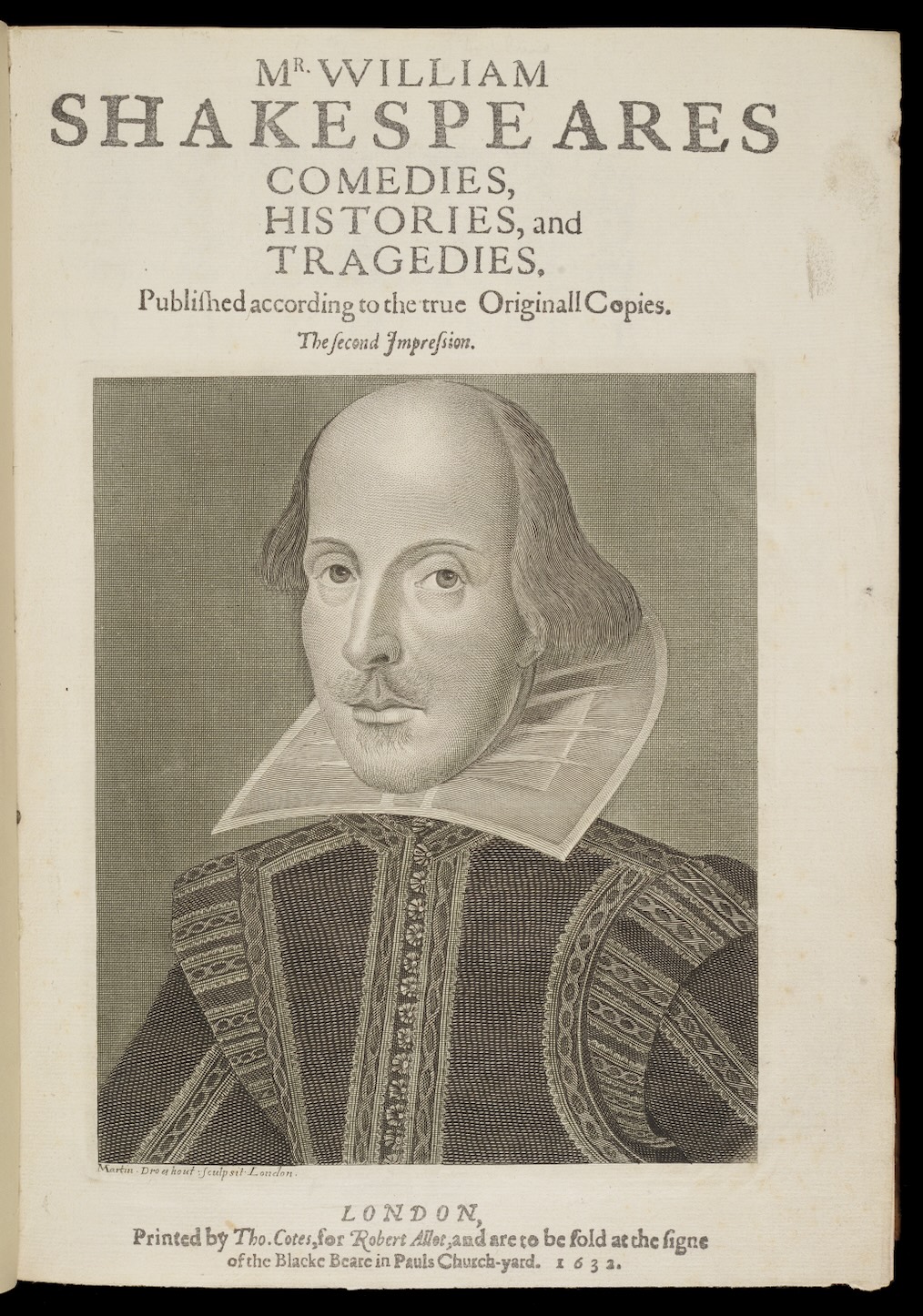

William Shakespeare’s Second Folio

Shakespeare, William. Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, and tragedies.

London, 1632.

William Shakespeare’s Second Folio (1632) is the second edition of Shakespeare’s collected plays and contains 36 plays written by the bard; the same plays as the First Folio. It was published 16 years after Shakespeare’s death by Thomas Cotes for a consortium of booksellers in London. There are over 1,700 changes to the text between the printing of the First Folio and the Second Folio. By the time it was printed in 1632, many of Shakespeare’s plays were 40 years old and some of the original language used was considered archaic. Hence, the publisher modernized the language for their readers. The Second Folio is the most commonly used edition for modern publications of William Shakespeare. This is considered one of the first publications of a playwright’s collected works. Many authors followed this pattern in future years and printed their collection of works in a single volume.

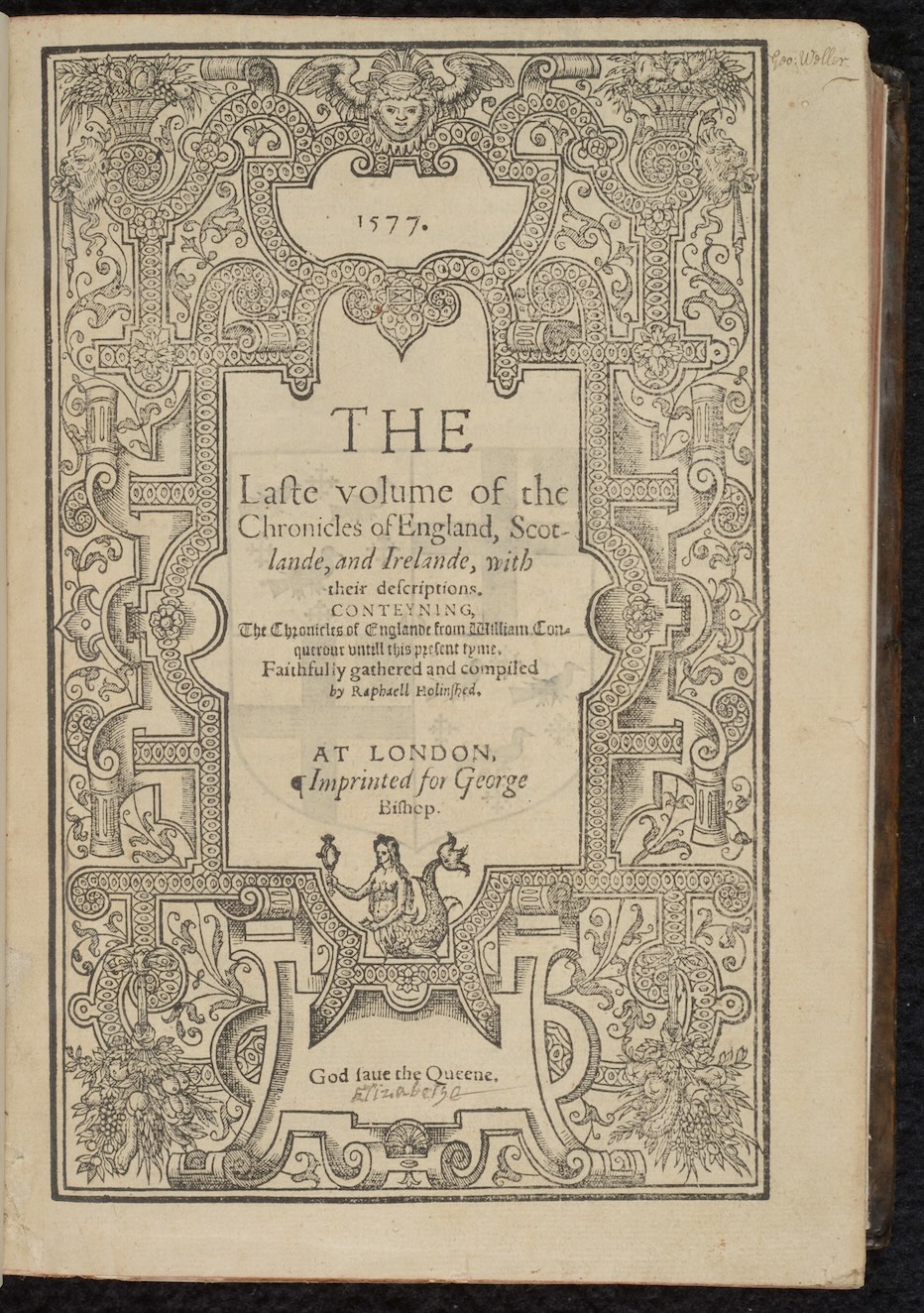

Shakespeare’s Primary History Book

Holinshed, Raphael. Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande. Conteyning, the description and chronicles of Scotland, from the first originall of the Scottes nation, till the yeare of our Lorde. 1571.

London: George Bishop, 1577.

This chronicle is a large, comprehensive description of British history covering England, Scotland, and Ireland. Holinshed’s Chronicle was a primary source for many Renaissance writers like Shakespeare, including Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spencer, and George Daniel. Although Shakespeare draws heavily on Holinshed, the primary difference is through characterization and exaggeration. For example, the Chronicles lack details on Macbeth’s personality, so Shakespeare improvised on several occasions in his plays.

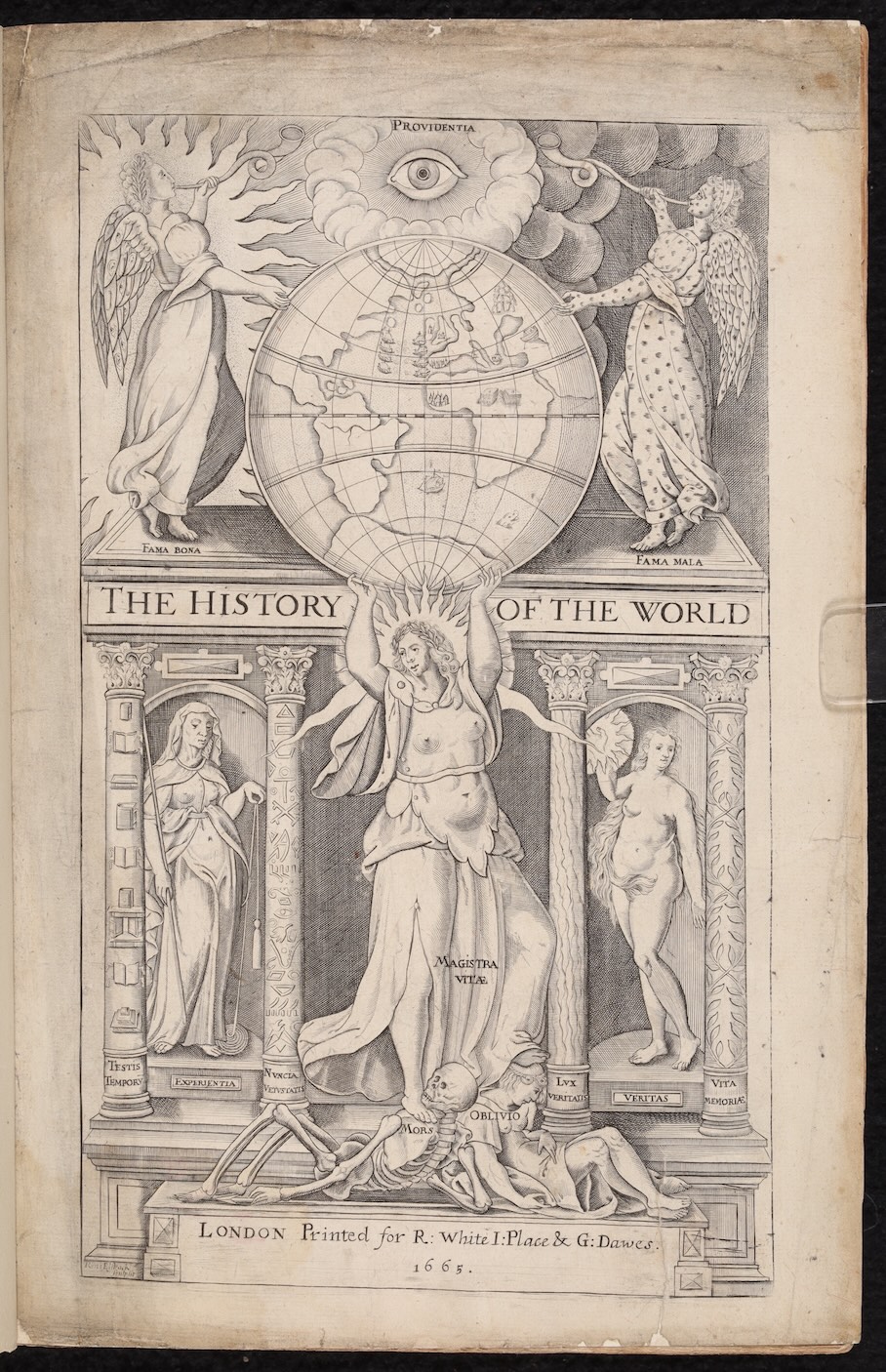

A World History, but mostly English History

Raleigh, Walter. The Historie of the World, in Five Books.

London: R. White, J. Place, and G. Dawes, 1666.

Sir Walter Raleigh played a leading role in the English colonization of North America, notably Virginia, fought in Ireland against rebels, and helped to defeat the Spanish Armada in 1588. After Elizabeth I died in 1603, Raleigh was imprisoned for his involvement in a plot against the new king, James I. He was executed by King James in 1618. The History of the World was written in the first seven years of incarceration. Several months after publication in 1614, James ordered further sales of the book suppressed. Many later editions, like the one on display, were not issued with the original title page and gave no authorial identification.

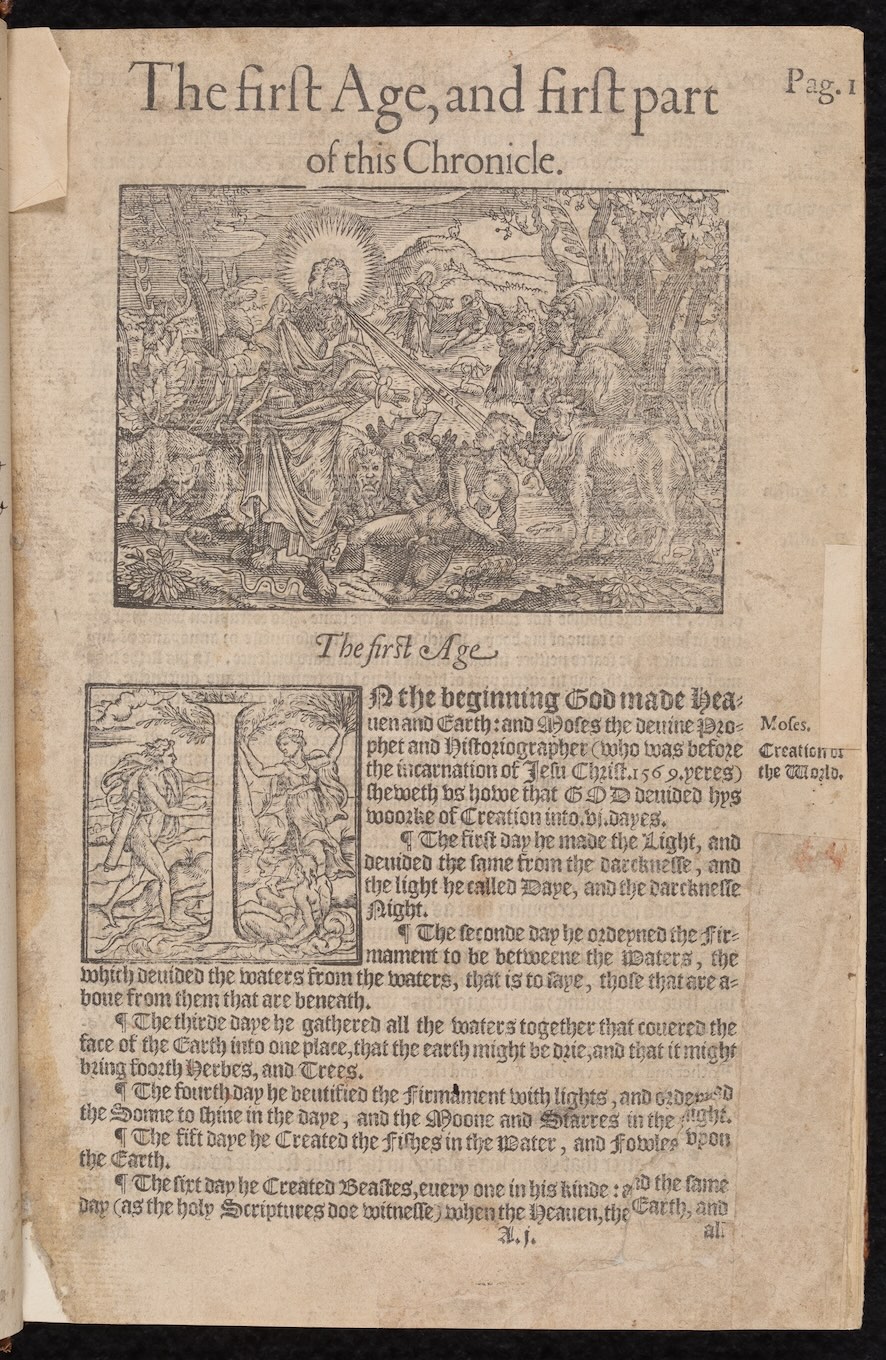

Handwritten and Revised History

Grafton, Richard. A Chronicle at Large, and Meere History of the Affayres of Englande, and Kinges of the Same.

London: R. Tottyl and H. Toye, 1569.

Richard Grafton (1506-1573) was the King’s Printer under Henry VIII and Edward VI. Grafton assisted in printing the Matthew Bible in 1537. A year later, he brought presses to London for the first edition of the Great Bible. Grafton was a supporter of the English Reformation and was imprisoned during Queen Mary’s reign as an anti-Catholic printer, which is where he compiled his Chronicle at Large.

Printed Medieval Chronicle of the Hundred Years’ War

Froissart, Jean (Chronicles) Here begynnith the First Volum of Syr John Froissart. 2 volumes.

London: Wyllyam Myddylton, 1525.

Jean Froissart’s Chronicles are the most detailed source for the Hundred Years’ War between England and France (1337-1453). It was originally written in the 14th century. The chronicles were originally written in French, but in the 15th and 16th centuries, the work was translated into Dutch, English, Latin, Spanish, Italian, and Danish. The English translation, dated 1523-1525, is one of the oldest historical prose works in English. This is an excellent example of the drive by Renaissance society to translate and study past literary works.

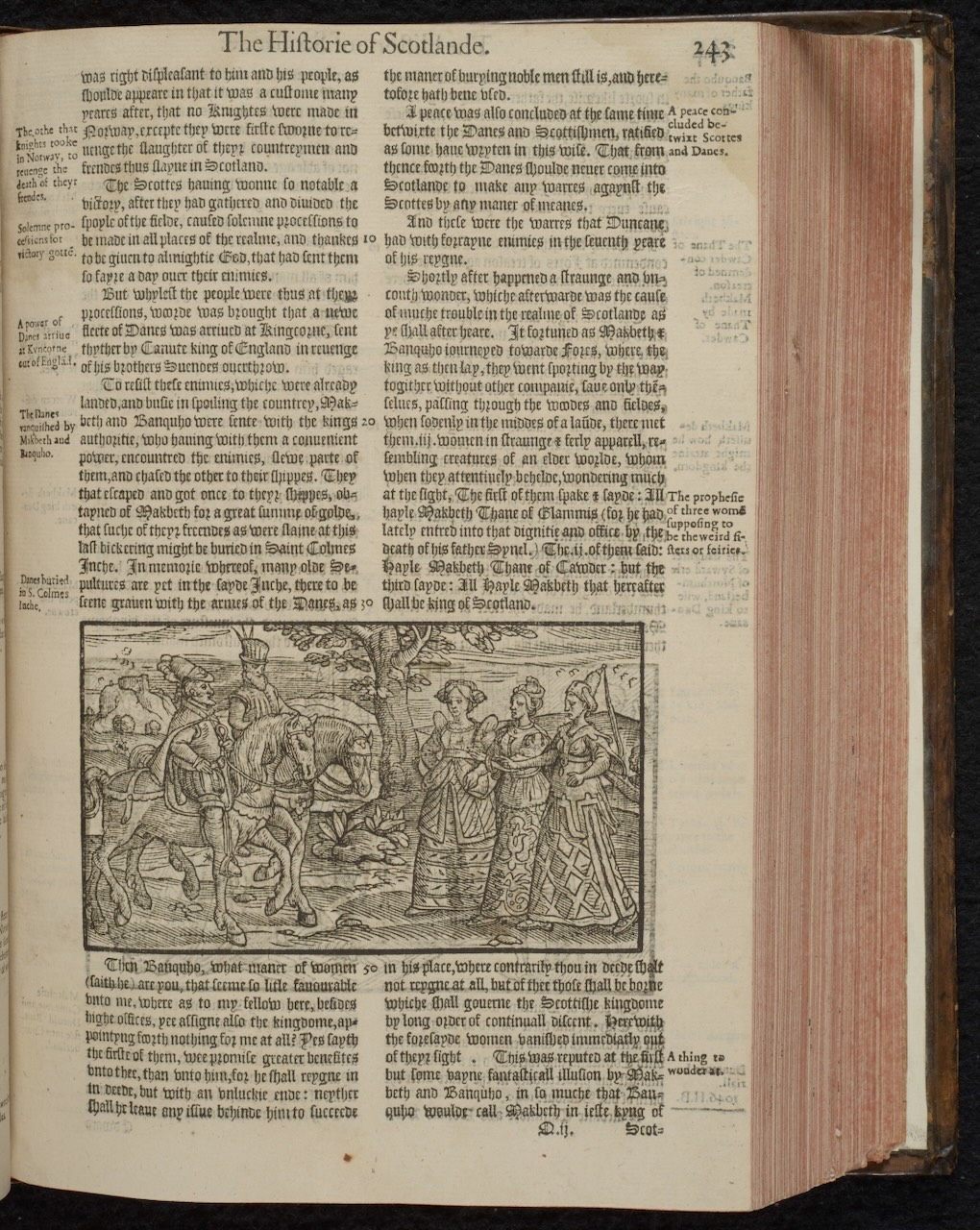

Inspiration for Macbeth

Woodcut details of Macbeth and Banquo encountering three women on the road from Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande.

London. 1577.

This chronicle is a large, comprehensive description of British history covering England, Scotland, and Ireland. Holinshed’s Chronicle was a primary source for many Renaissance writers like Shakespeare, including Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spencer, and George Daniel. Although Shakespeare draws heavily on Holinshed, the primary difference is through characterization and exaggeration. For example, the Chronicles lack details on Macbeth’s personality, so Shakespeare improvised on several occasions in his plays.

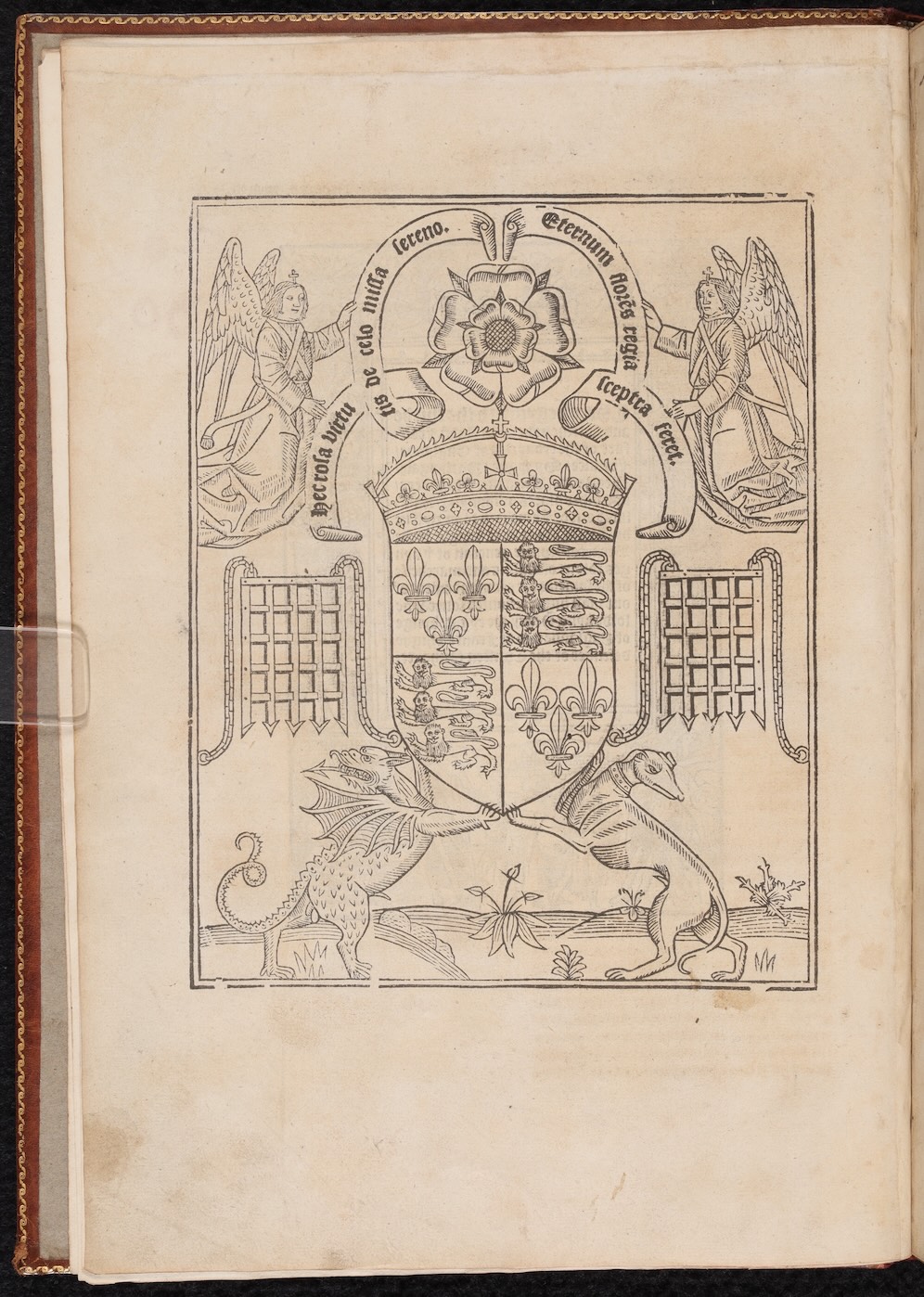

Image of King Henry VIII

Holinshed, Raphael. Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande. Conteyning, the description and chronicles of Scotland, from the first originall of the Scottes nation, till the yeare of our Lorde. 1571.

London: George Bishop, 1577.

On June 29, 1613, Shakespeare’s play King Henry VIII was performed at the Globe Theatre in one of the play’s first-ever performances. Cannons were used to signal the king’s entrance, which accidentally set the roof on fire. The whole theatre burned to the ground. Holinshed’s presentation of Henry VIII in his Chronicle is one of excitement and possibility. Henry VIII was Queen Elizabeth I’s father, so a play about his reign needed to carefully walk the line. The Chronicle is open to the first page of Henry’s reign where a small woodcut of the king is presented.

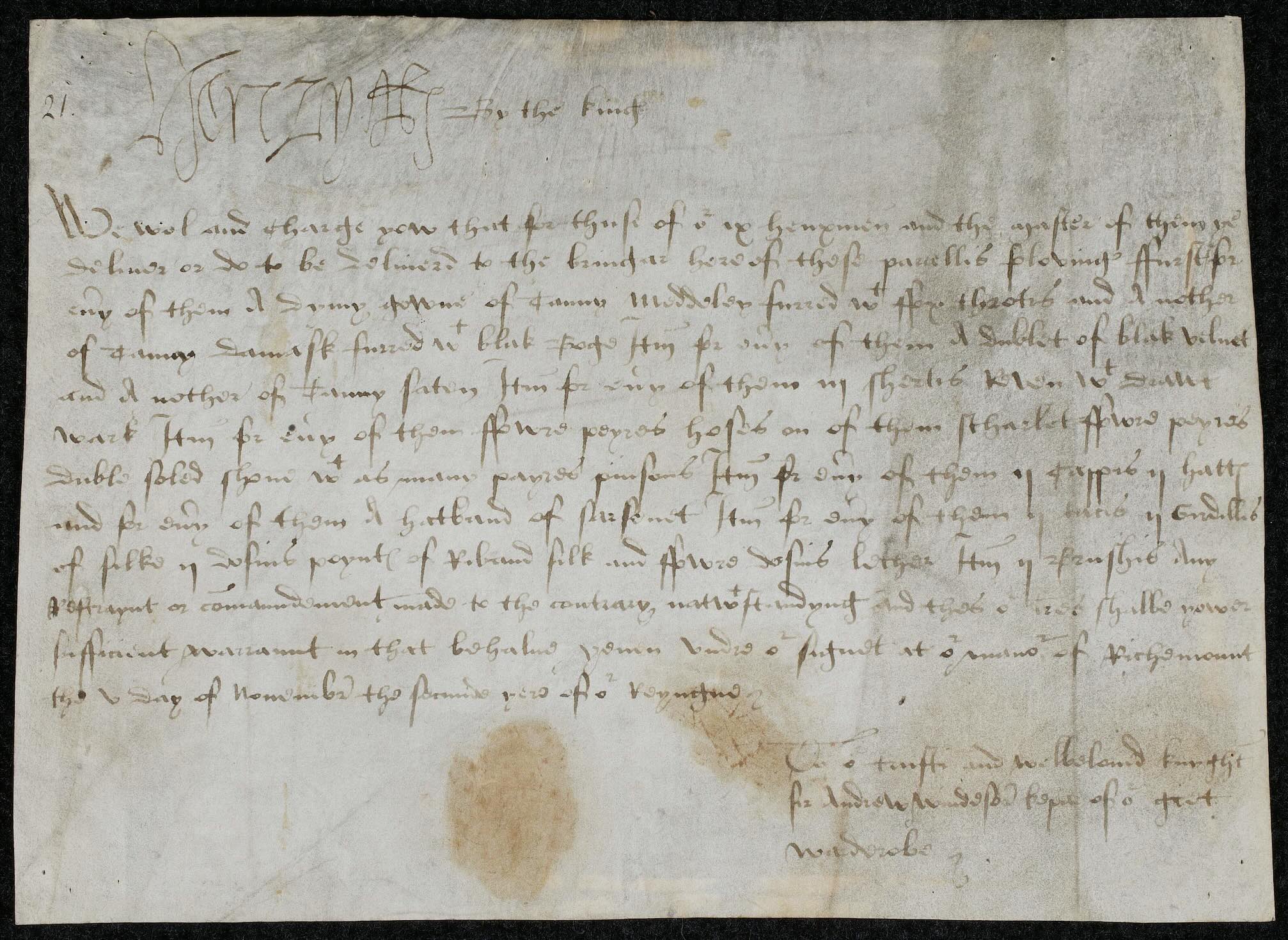

Kingly Correspondence

Letter from King Henry VIII, Richmond, London, England, to Sir Andrew Windsor, Keeper of the Great Wardrobe.

London, 1510.

An order to the Royal Exchequer, signed in full by the King in the upper left-hand corner, ordering new uniforms, fur coats, and hoses for his royal pages. This letter features the signature of King Henry VIII just over a year after ascending the throne and was a very young king at just 18 years old when he wrote this letter. Providing uniforms for his servants was part of their compensation for employment in the royal household. Incoming monarchs like to provide new uniforms to their servants as a visual difference to the previous reign.

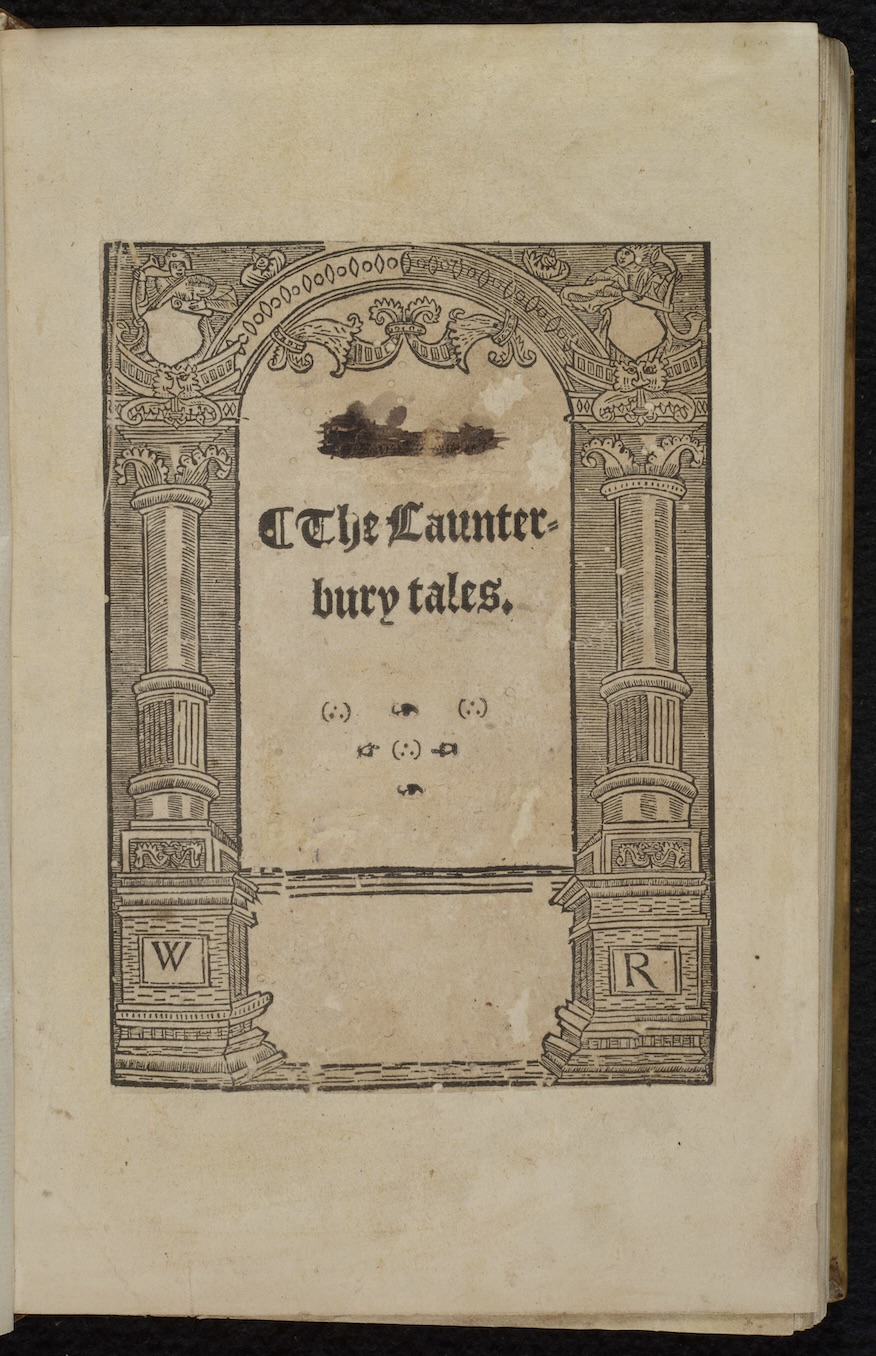

Printed Version of The Canterbury Tales

Chaucer, Geoffrey. The workes of Geffray Chaucer newlye printed, wyth dyuers workes whych were neuer in print before.

London: W. Bonham, 1542

Geoffrey Chaucer (1341-1400) was an English poet best known for The Canterbury Tales. He has been called the “father of English poetry”. He is seen as a crucial part of legitimizing the English language as a language of literature. At the time, Anglo-Norman French and Latin still dominated the literary scene. Early modern readers were still interested in Chaucer’s writing centuries after it was originally composed. This edition, published in 1542 was edited by William Thynne and contains “The Plowman’s Tale” which was not included in Chaucer’s original manuscript.

Shakespeare’s Contemporaries

During Queen Elizabeth’s 60-year reign, England produced many of the greatest writers of English literature. One reason for this was the queen fostered an atmosphere at her court that patronized writers and poets. Elizabeth I was known to invite theatre companies to perform at her palaces during holidays and celebrations. She even sponsored her own theatre company, Queen Elizabeth’s Men, which was a troupe of actors formed in 1583.

Poetry especially developed a uniquely English style at this time characterized by the development of language and extensive allusion to classical myth. For example, Edmund Spencer (c.1552-1599) was one of the most important poets of the period and wrote The Faerie Queene between 1590 and 1596. It is an epic poem written in allegory that celebrates the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I, specifically. By impressing the queen, a writer might receive royal favor and patronage. However, Elizabeth also had a strong hand when it came to censorship, especially about her person and ancestry. So much so that in 1559, a year after she became queen, Elizabeth I proclaimed that no play should be performed that dealt with “either matters of religion or of the governance of the estate of the common weal[th].” Although there was a flourishing literary scene, Elizabeth’s reign marked a high point in royal censorship, so many writers walked a fine line of creativity and appeasing the monarch.

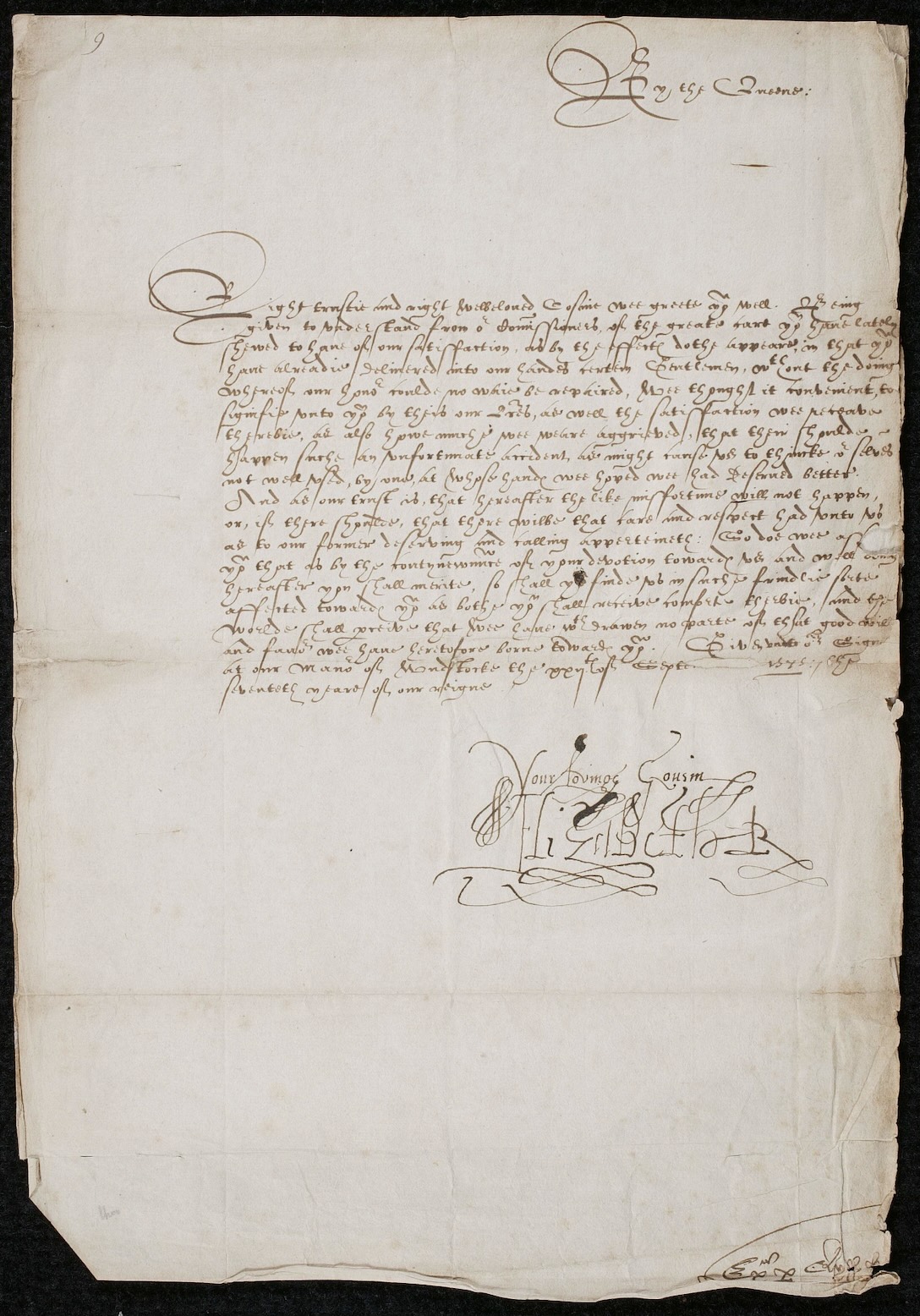

Signature of the Queen

Letter from Queen Elizabeth I, Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England, to James Douglas, Regent of Scotland, 1575 September 26.

Woodstock, 1575.

This letter was written by Queen Elizabeth I, in September 1575 to James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton and Regent of Scotland during James VI’s minority. The letter addresses a mishap that happened on the Anglo-Scottish border, wherein the Earl of Morton detained several English gentlemen, including Sir John Forster, at the border by accident. Douglas quickly apologizes to the Queen and declares the prisoners released upon bond to not cause further trouble on the border. This is the Queen’s reply: she is not pleased that her subjects were imprisoned even if by accident.

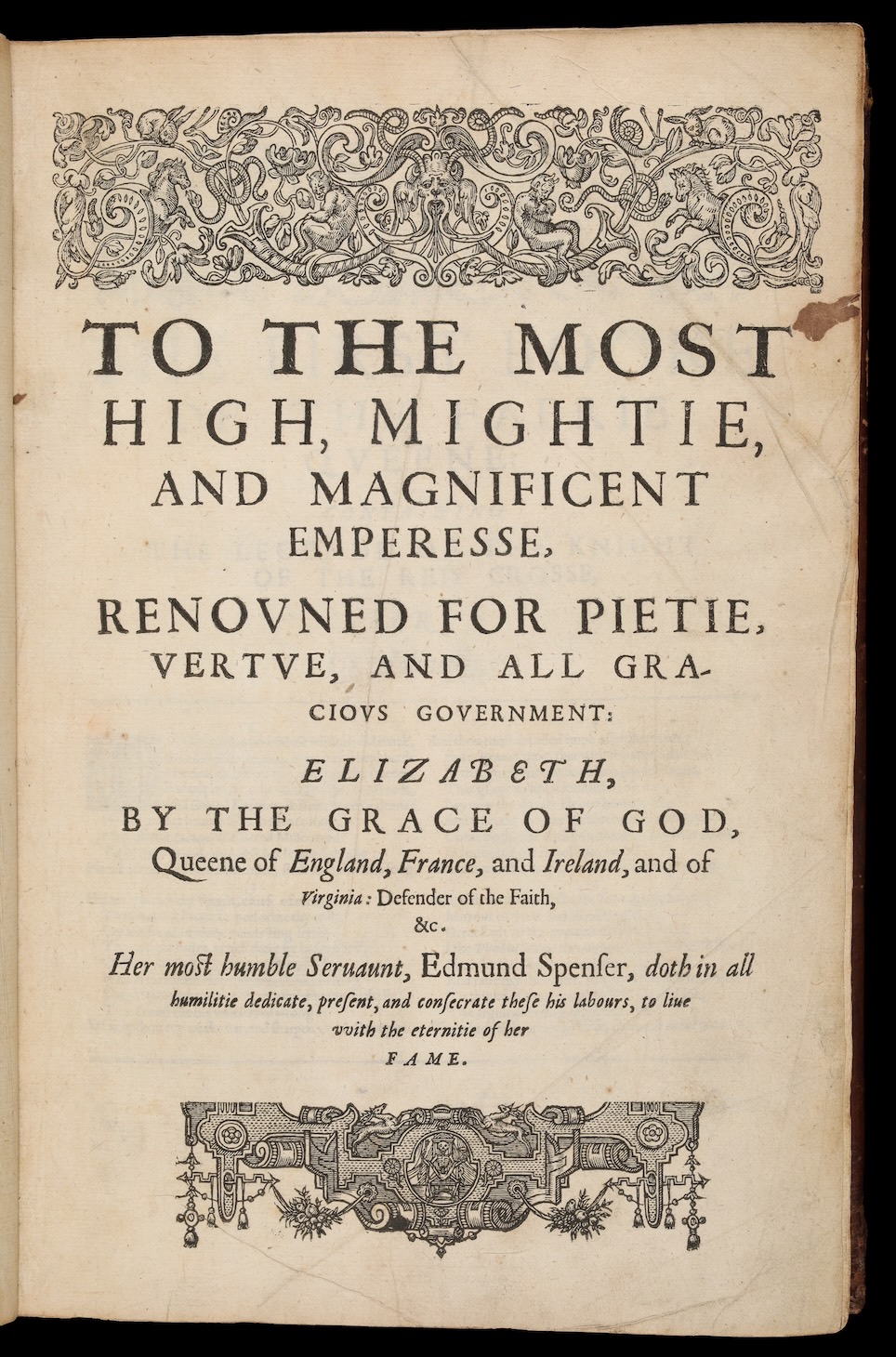

Allegorical Writing About the Queen

Edmund Spenser. The Faerie Queen.

London, 1611.

The Faerie Queene is an epic poem by Edmund Spenser. It is one of the longest poems in the English language. The poem follows a group of knights as they examine different virtues. As it is an allegorical treatise, it can be read on several levels, including famously, as praise (or, criticism) of Queen Elizabeth I. The Queen appears in the guide of Gloriana, the Faerie Queen. In Spencer’s own words, the entire poem is “cloudily enwrapped in Allegorical devices” and the aim was to “fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline”.

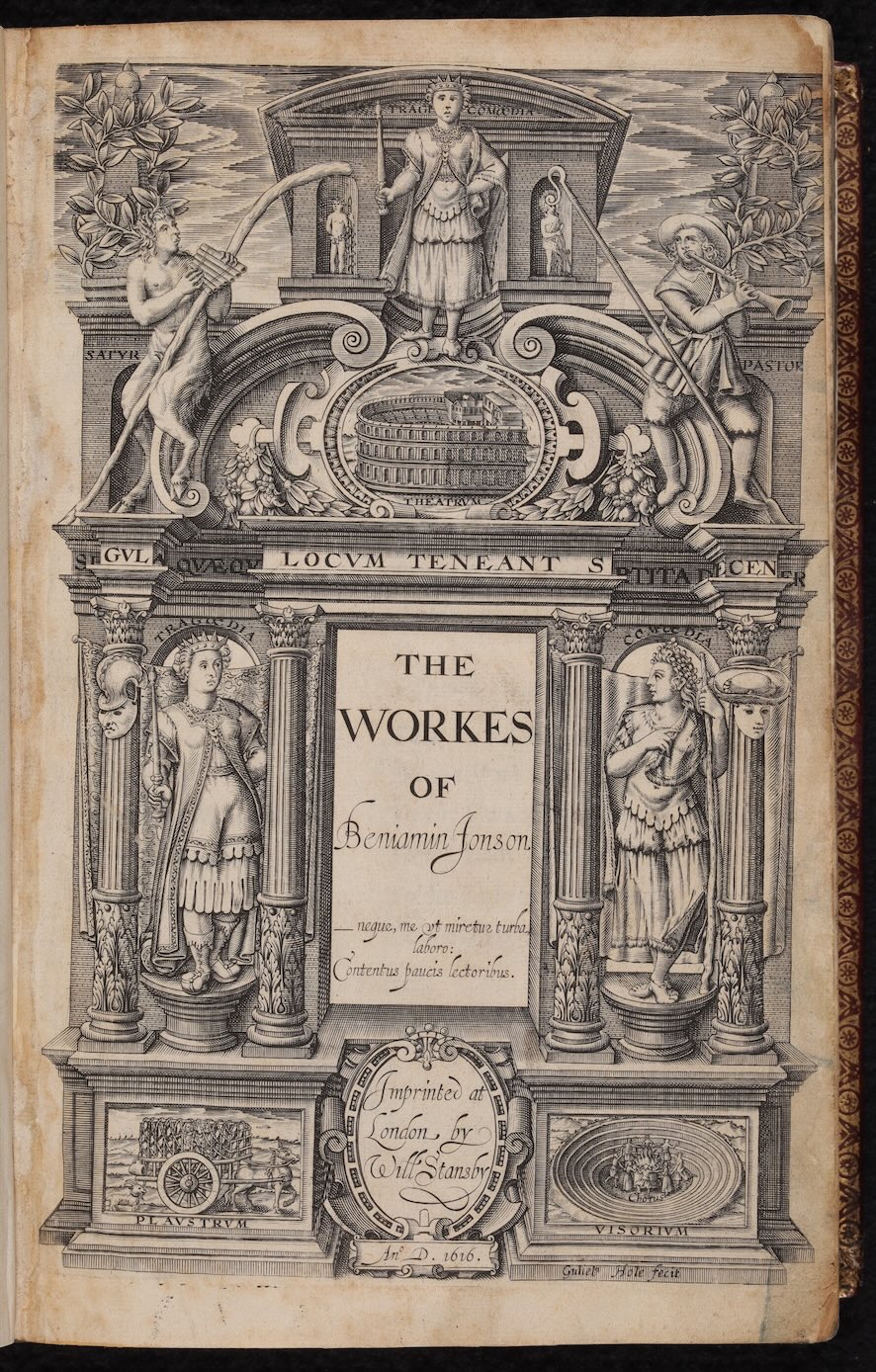

Shakespeare’s Friend and Fellow Author

Jonson, Ben. The Workes of Beniamin Jonson.

London: W. Stansby, 1616.

Ben Jonson (1572-1637) is regarded as one of the most important poets of the English Renaissance alongside Shakespeare. Shakespeare was among the first actors to be cast in Jonson’s comedy. Jonson published his collected works in 1616, the first edition. This was the first time English plays were collected and presented in this way, and this collection paved the way for the publication of his friend, and sometimes rival, Shakespeare’s First Folio. The first edition, as seen here, treated stage plays as serious literature works and helped to preserve these plays for the future.

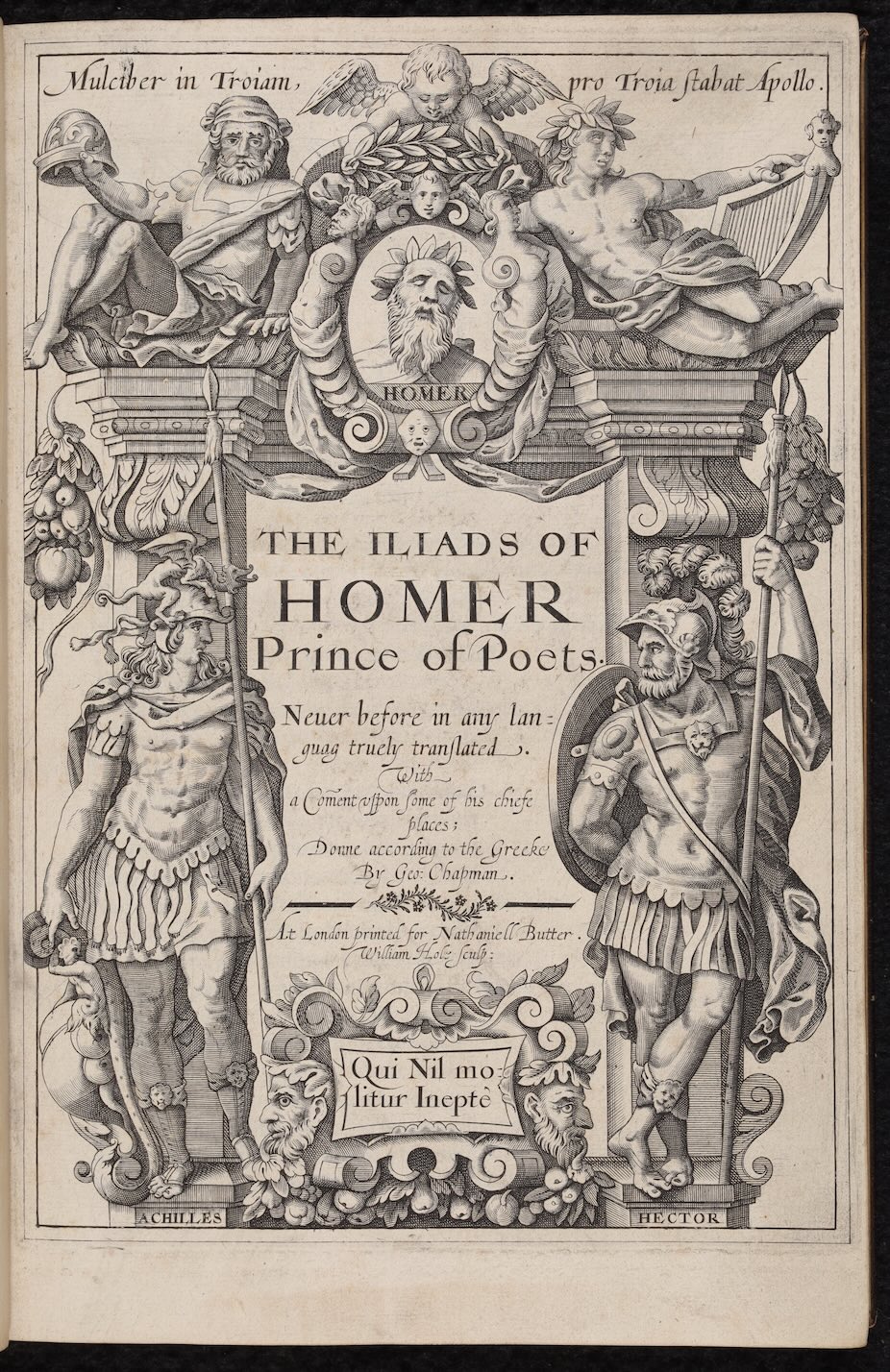

First Translation of Homer’s The Iliad

Homer and George Chapman. The Iliads of Homer, Prince of Poets. Neuer before in Any Language Truely Translated.

London: N. l. Butter, 1615

George Chapman’s (c.1559-1634) edition and translation of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey mark the first translation of the text into English from the original Greek. Previous English translations of Homer’s work were indirect translations, meaning they were translations from translations. There is some speculation that Chapman is the unnamed “rival poet” of Shakespeare’s sonnets (in sonnets 78-86). Unfortunately, Chapman, unlike Shakespeare, struggled to keep a patron and stay out of debt, due to the premature death of two patrons and several lawsuits filed against him.

Literature during the English Civil War

The Renaissance could not last forever, and by the mid-seventeenth century, Britain was on the brink of civil war and constitutional crisis. England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland were plunged into conflict between the King and Parliament, each vying for power.

Starting around 1639 and lasting for over 20 years, Britain faced civil war, the execution of Charles I, military rule under Oliver Cromwell, and the restoration of the monarch in 1660 with Charles II. It was a time of crisis rather than rebirth.

Major societal shifts inevitably caused changes to the writing, printing, buying, and consumption of literature. Newspapers, pamphlets, and journalism moved to the forefront as people demanded to know current events. Several tangible changes can be seen during, and subsequently after, the English Civil War that impacted literary activity to its core:

- Royal censorship came to an end, during the Civil War, and the level of publications rose, leading to a pamphlet war between opposing sides.

- The theatres were closed down and the performance of plays was suppressed.

- The theatrical migrated into pamphlets and newsbooks, with playwrights becoming journalists and actors sometimes soldiers.

- Royalist literature was forced underground as those who opposed the monarch gained more popularity and power.

- Greater freedom in religious worship resulted in the rise of new literary forms as part of new devotional practices.

Although many in Britain welcomed the monarchy back with the Stuart Restoration of King Charles II in 1660, literature and print would never be the same again.

Poetry after the English Civil War

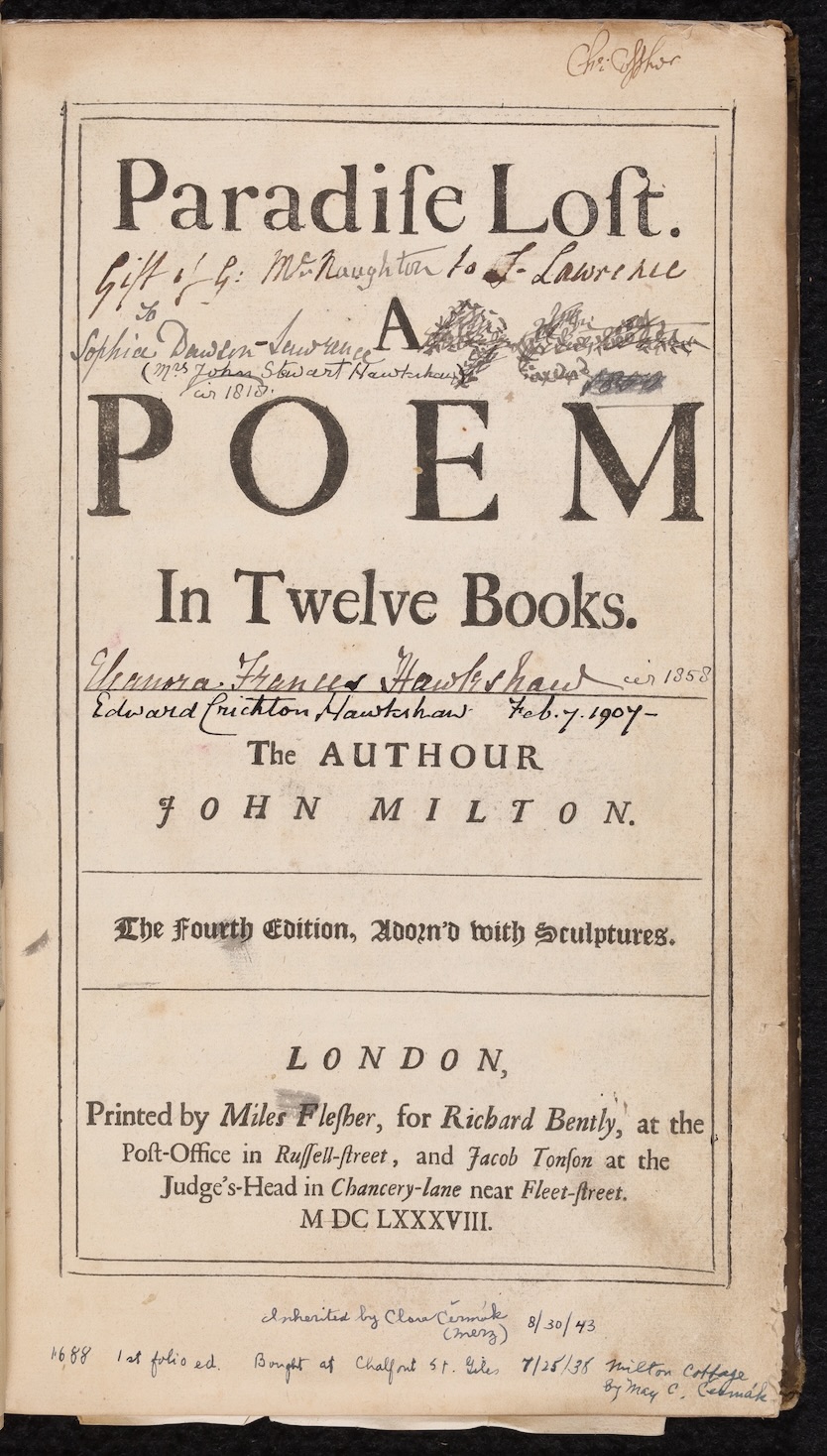

Milton, John. Paradise Lost. Illustrated.

London: R. Bently and J. Tonson, 1688.

John Milton (1608-1674) is most well-known for his epic poem, Paradise Lost, written in 1667. It was written at a time of intense religious and political upheaval. The poem addresses the fall of man, the temptation of Adam and Eve, and God’s expulsion of them from the Garden of Eden. Samuel Johnson described Paradise Lost as “a poem which…with respect to design may claim the first place”. The poem was written towards the end of his life when he was blind and impoverished after the failure of the English Revolution and the Interregnum period. It is considered one of the most significant allegorical poems about monarchy to be written in this period.

Authors Influenced by Shakespeare

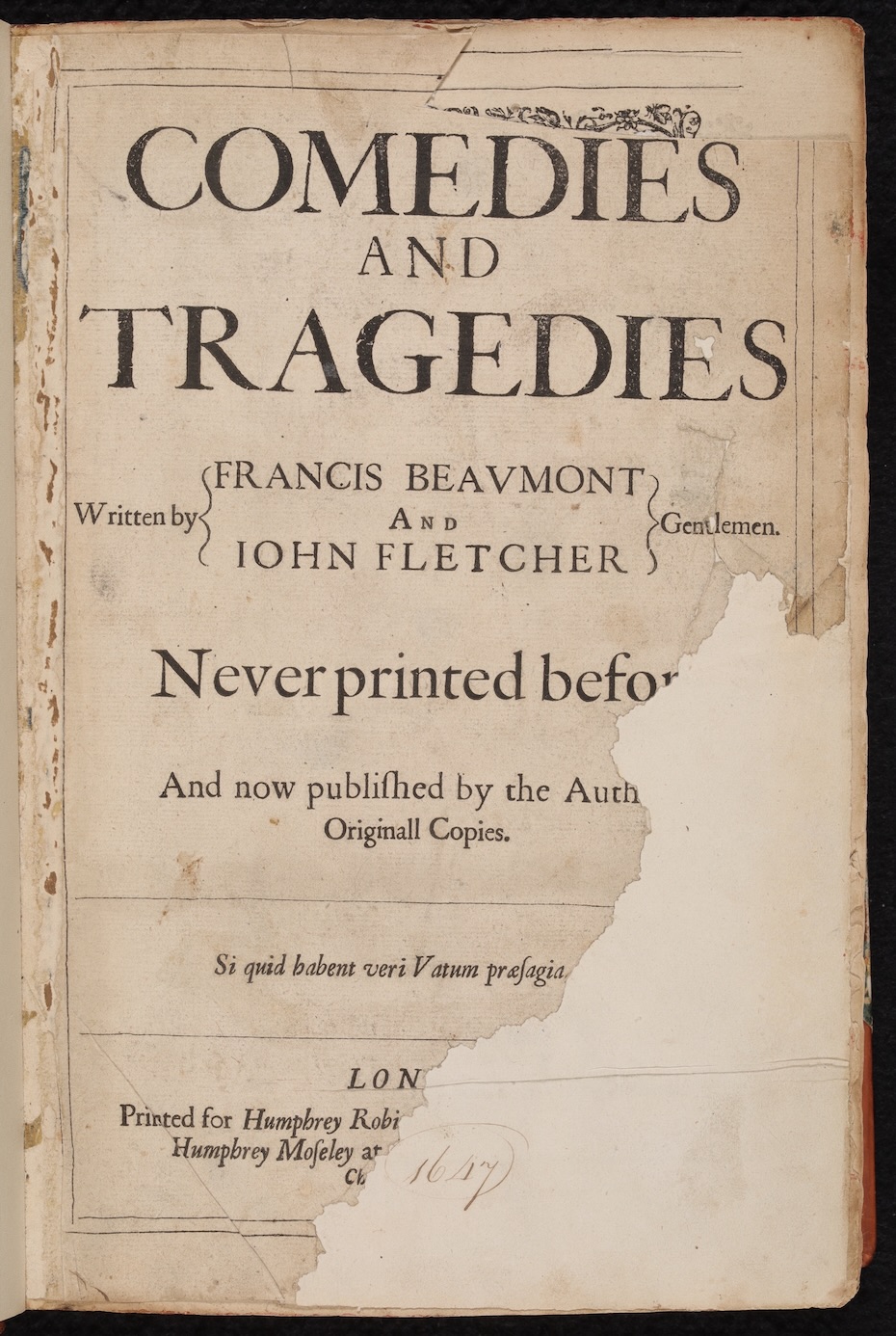

Beaumont, Francis, and John Fletcher. Comedies and Tragedies.

London: H. Robinson and H. Moseley, 1647.

This folio was modeled on those of William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, the 1647 first edition of “Comedies and Tragedies” comprises all of the hitherto unpublished plays of Beaumont and Fletcher with the exception of the “Wild-Goose Chase” which was not printed until 1652. This folio contains 35 works in total – 34 plays and 1 masque. Many of the plays were previously published as individual volumes. This was, however, the first time they were all brought together.

Living Through a Civil War

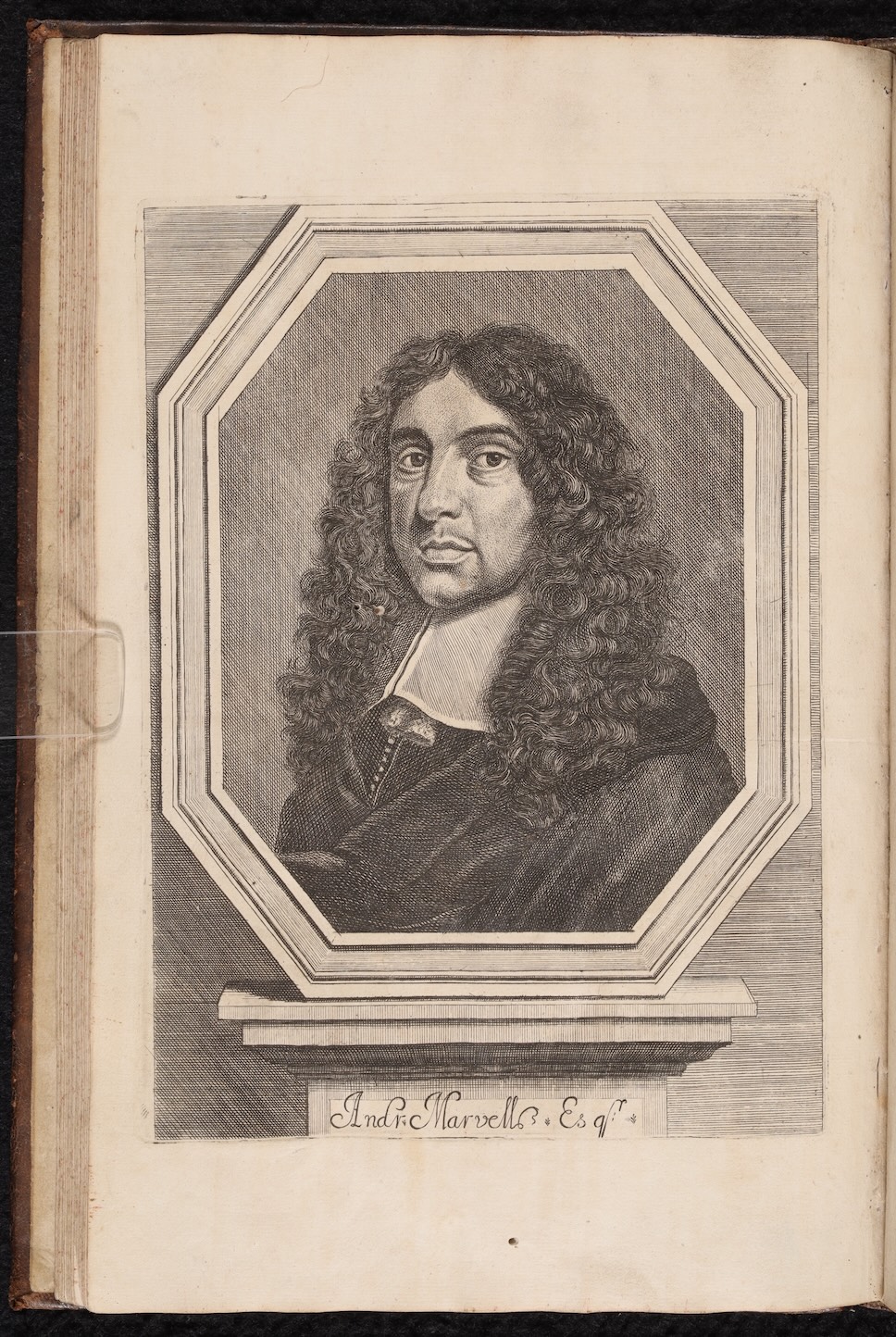

Marvell, Andrew. Miscellaneous Poems. [Bound with John Davies, Nosce Teipsum (1689)].

London: R. Boulter, 1681.

Andrew Marvell was a poet and satirist, who was a colleague and friend of John Milton. He even helped to convince the restored king, Charles II, to not execute John Milton for his anti-monarchical writings and revolutionary activities during the English Civil War. After the Restoration of the king, Marvell anonymously published several long and bitterly satirical verses against the corruption of the court. The poems were too dangerous to be published under his name originally. Many were not published under his name after the deposition of James II, known as the Glorious Revolution.

Language and Censorship

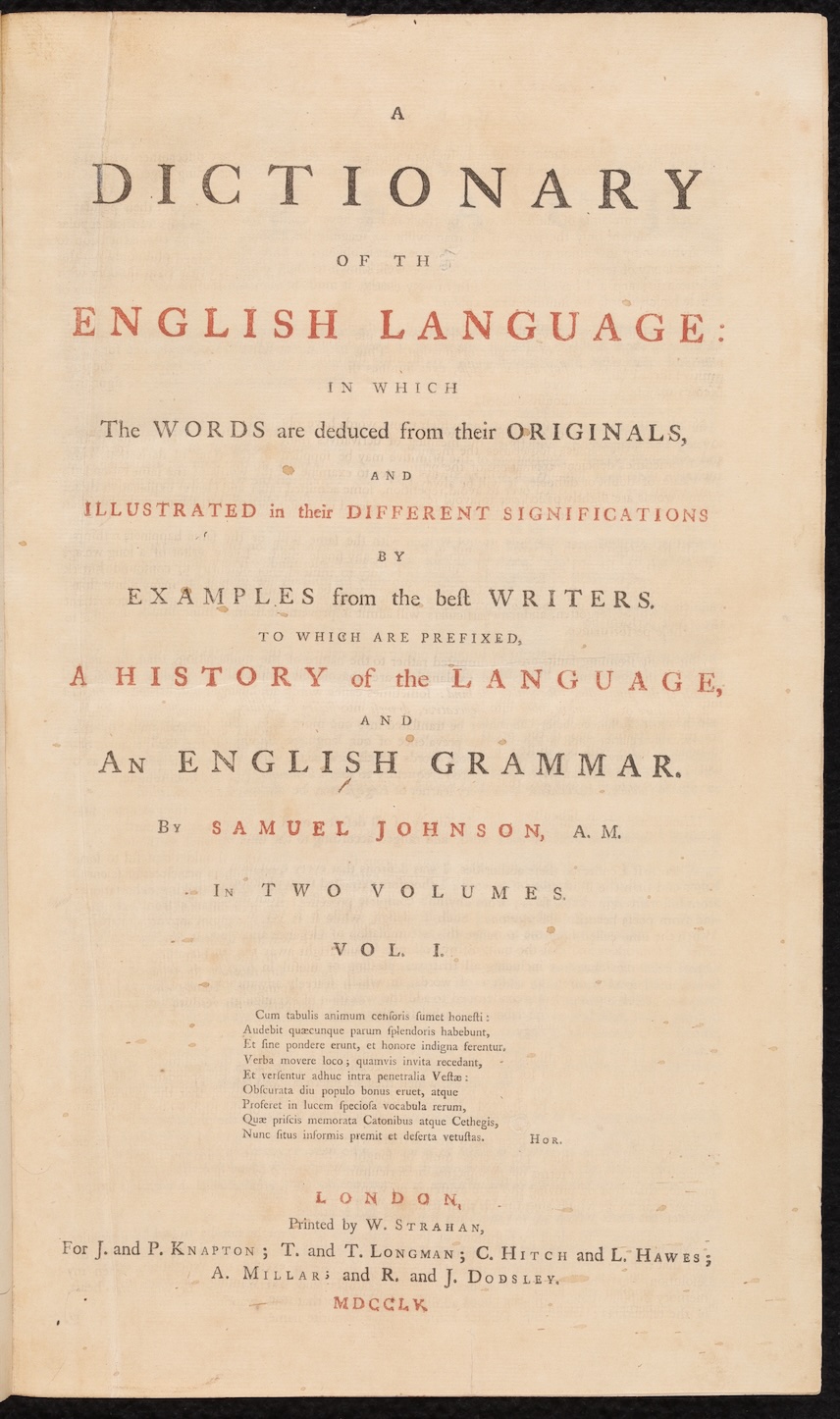

In 1755, after nine years, six assistants, 42,773 entries, and over 140,000 definitions, Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) published the first modern English dictionary, Dictionary of the English Language. It was printed in large, folio size, and outside a few special editions of the Bible, no book of this heft and size had ever been set to type in Europe. All modern dictionaries largely follow Johnson’s entry structure: entry word, pronunciation, part of speech, origin, and definition.

One of Johnson’s innovations was to illustrate the meaning of his words through literary quotations, of which there are around 114,000. Johnson cites Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden more than any other authors. William Shakespeare alone was cited more than 17,500 times in the dictionary—15% of the total quotations.

A Dictionary of the English Language

Title page from Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language.

London, 1755.

The Dictionary of the English Language exemplifies the contradicting ideologies surrounding language in the 18th century: the belief that there was a need for language to remain constant, but, as humans, change is inevitable. The Dictionary was a pivotal moment in the standardizing of language and ensuring a sense of uniformity as more and more people were writing and reading in English.

Tricks of the Trade: Printing Banned Books

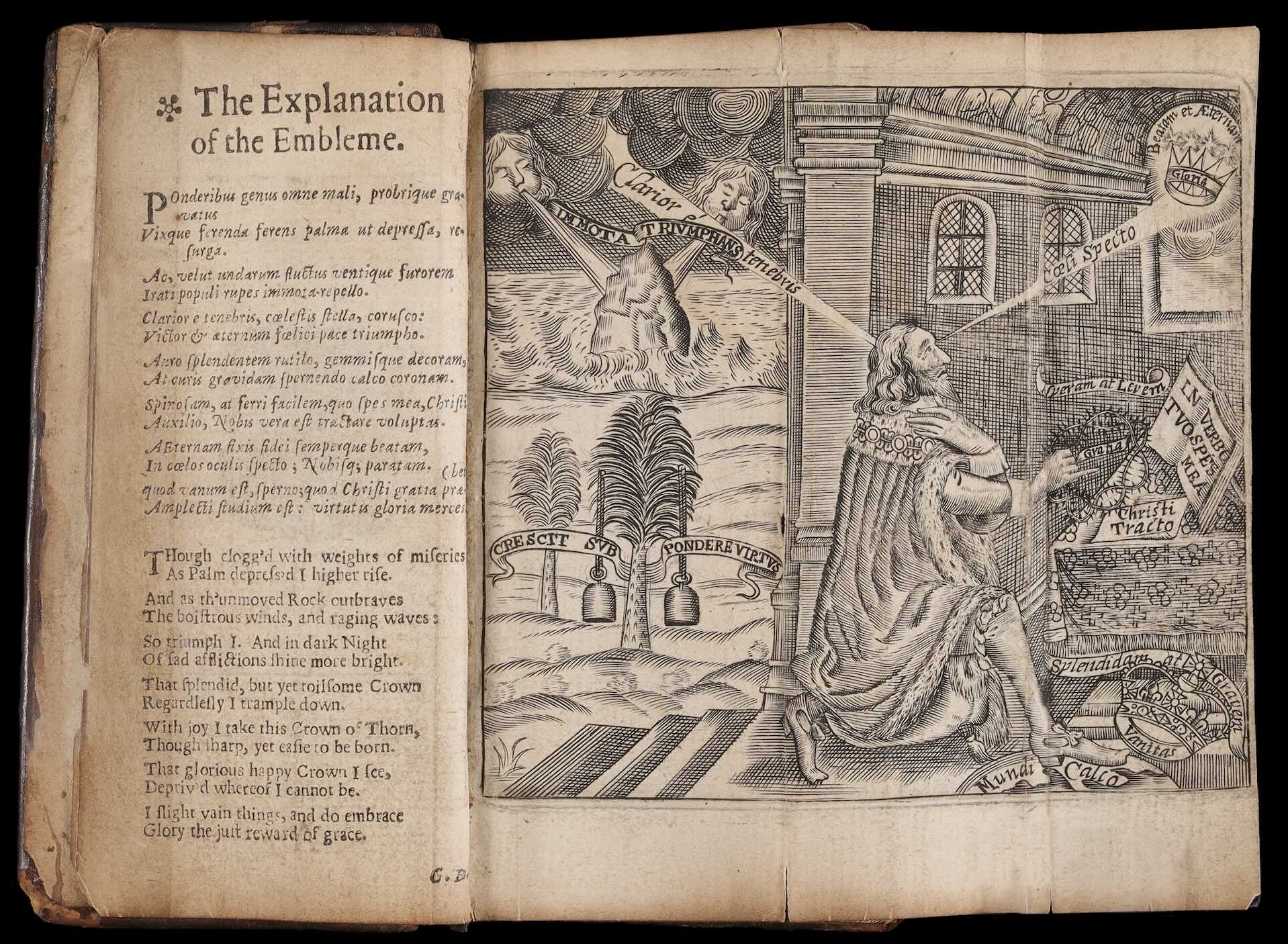

Gaudin, John. Eikon Basilike. The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in His Solitudes and Sufferings. 2nd Edition (False imprint of 1649).

London, 1657.

Despite Parliament’s attempts at suppression, Eikon was one of the most widely printed English books of the seventeenth century. Printed eight years after Charles I’s execution, this edition lacks publisher identification and bears a false imprint of 1649. Printers worked discreetly, risking punishment by Parliament. Whether driven by belief or profit, printers produced pocket-sized editions like this one so that the book could be easily concealed by its owner. The frontispiece depicts a saint-like Charles I kneeling and gazing upward at a divine crown, while the crown of England lies beneath him.

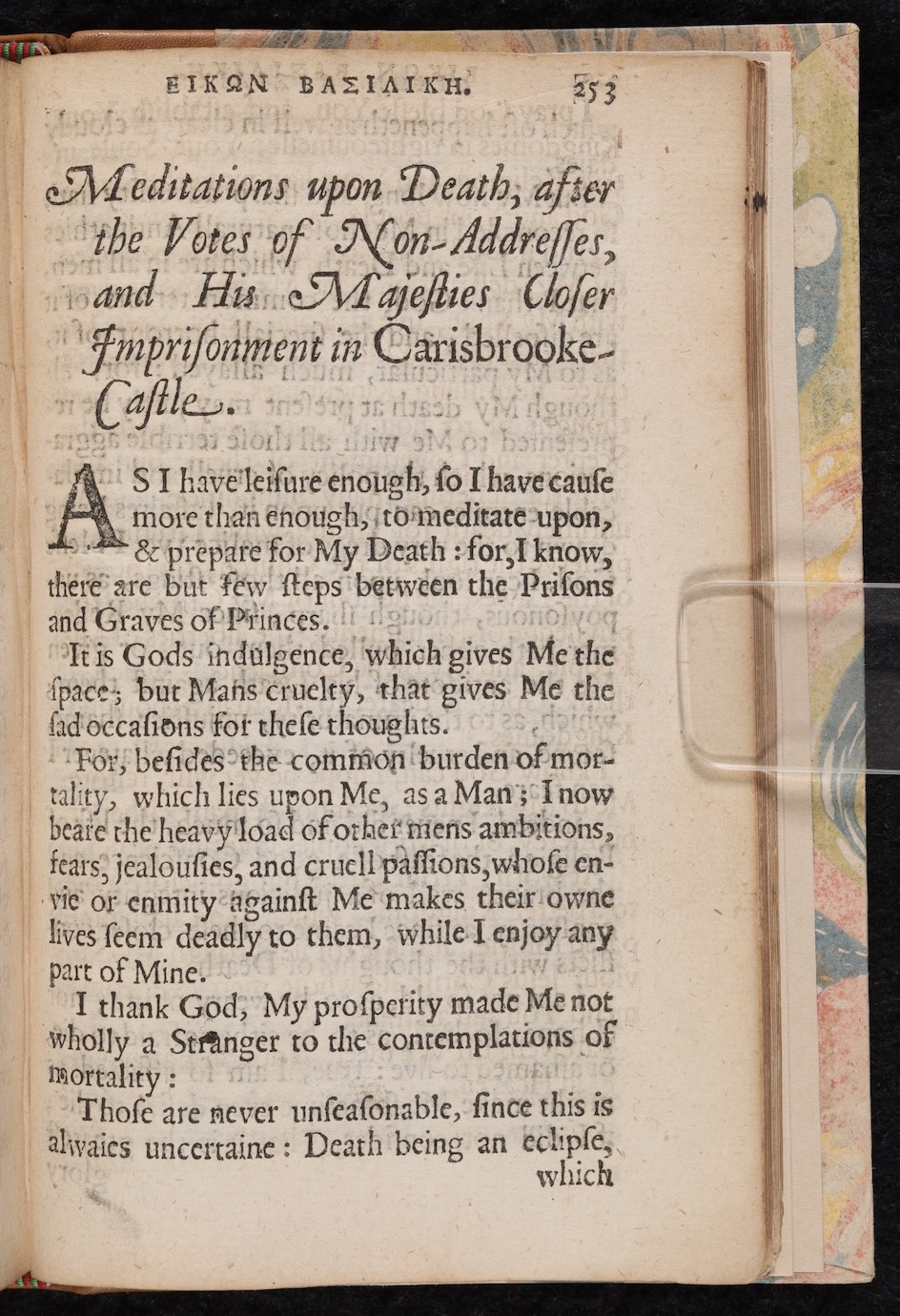

Reshaping the Memory of a King

Gaudin, John. Eikon Basilike. The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in His Solitudes and Sufferings.

London: R. Royston, 1649.

Originally believed to have been written by King Charles I (1600-1649) during the English Civil War (1642-1651), Eikon is now attributed to John Gaudin (1605-1662). Gaudin organized the king’s writings from the years 1640 through 1645 and added his own work, molding the king’s legacy into a sympathetic one. As the fate of Charles I became clear, final edits were made to Eikon, most notably the title was changed from Suspiria Regalia (The Royal Plea) to Eikon Basilike (Portrait of the King), acknowledging that pleas to Parliament would not reverse the verdict of treason. Eikon was distributed shortly after his execution in 1649.

Portrait of a King

Portrait of King Charles I

19th century

King Charles I reigned over Great Britain and Ireland from 1625 until 1649 when he was tried for treason and executed by Parliament as part of the English Civil War. The English Civil War was a conflict between the Royalists and Parliamentarians from 1642 to 1651. The war was part of the larger Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which lasted from 1639 to 1653. A major contention by Parliamentarians was the sheer amount of monarchical power wielded by the king. Charles I believed in the Divine Right of Kings, the idea that kings are intended by God to rule. This belief caused his authoritative reign to be marked by conflicts with Spain, France, Scotland, and his own Parliament. In April of 1642, Charles I moved to York, and by August both he and Parliament were prepared for the war that would end in the first, and only, execution of an English monarch. The next 15 years witnessed the rise of Oliver Cromwell’s authoritarian regime and the restoration of the British monarchy in 1660 with King Charles II.

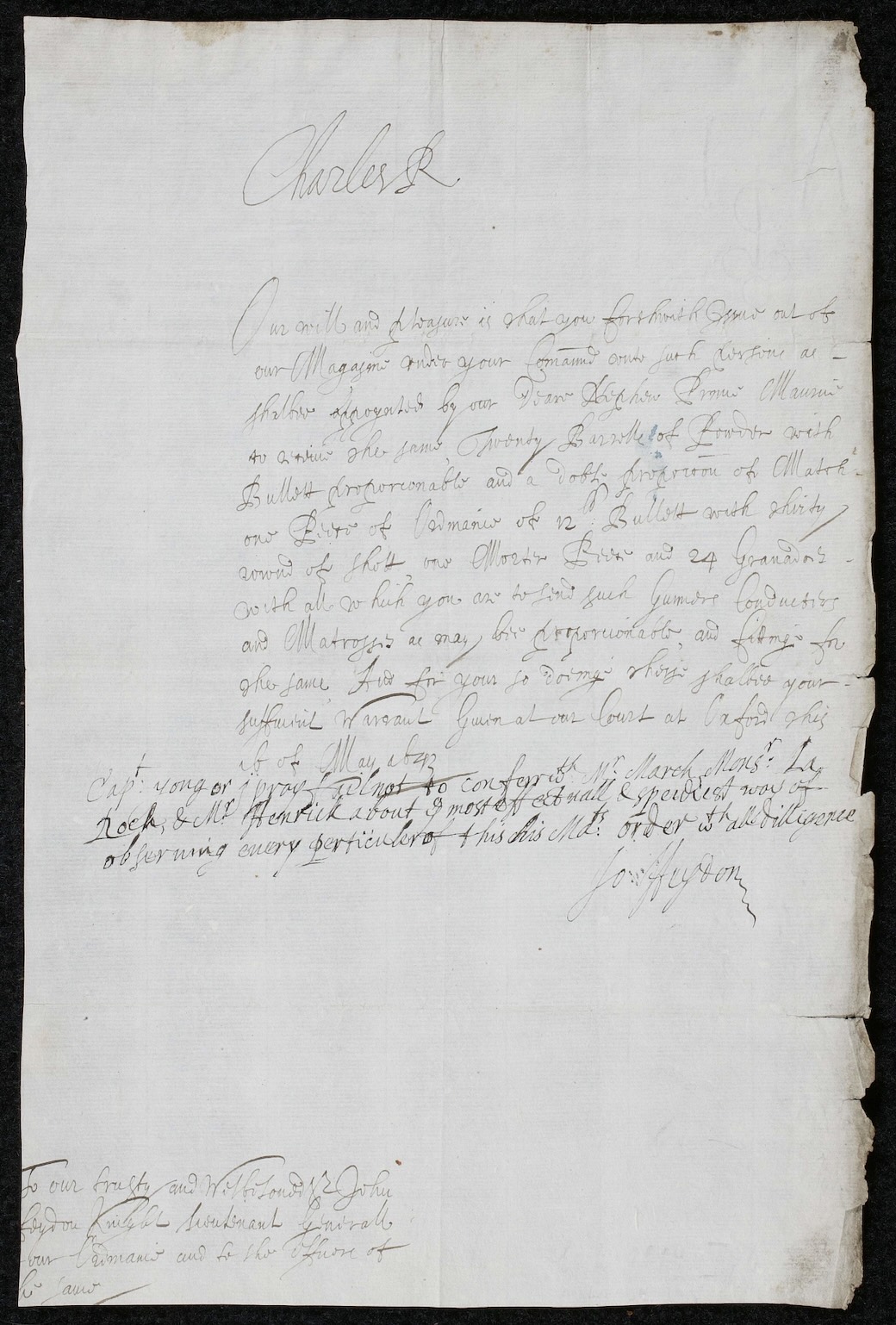

Writings from the King’s time in Oxford

Letter from King Charles I, Oxford, England, to Lt. General John Heydon, 1643 May 16.

Oxford: 1643.

In October 1642, two months after the English Civil War began, King Charles I moved his headquarters from London to Oxford, distancing himself from Parliament and building his defenses in a city loyal to the Crown. The Royalist occupation of Oxford lasted four years, during which Charles I sent this letter in May of 1643 ordering General John Heydon to distribute arms, and he continued writing his meditations, later included in Eikon Basilike. In the same year Charles I published A Forme of Common Prayer, appointing Oxford University’s press as the printer.

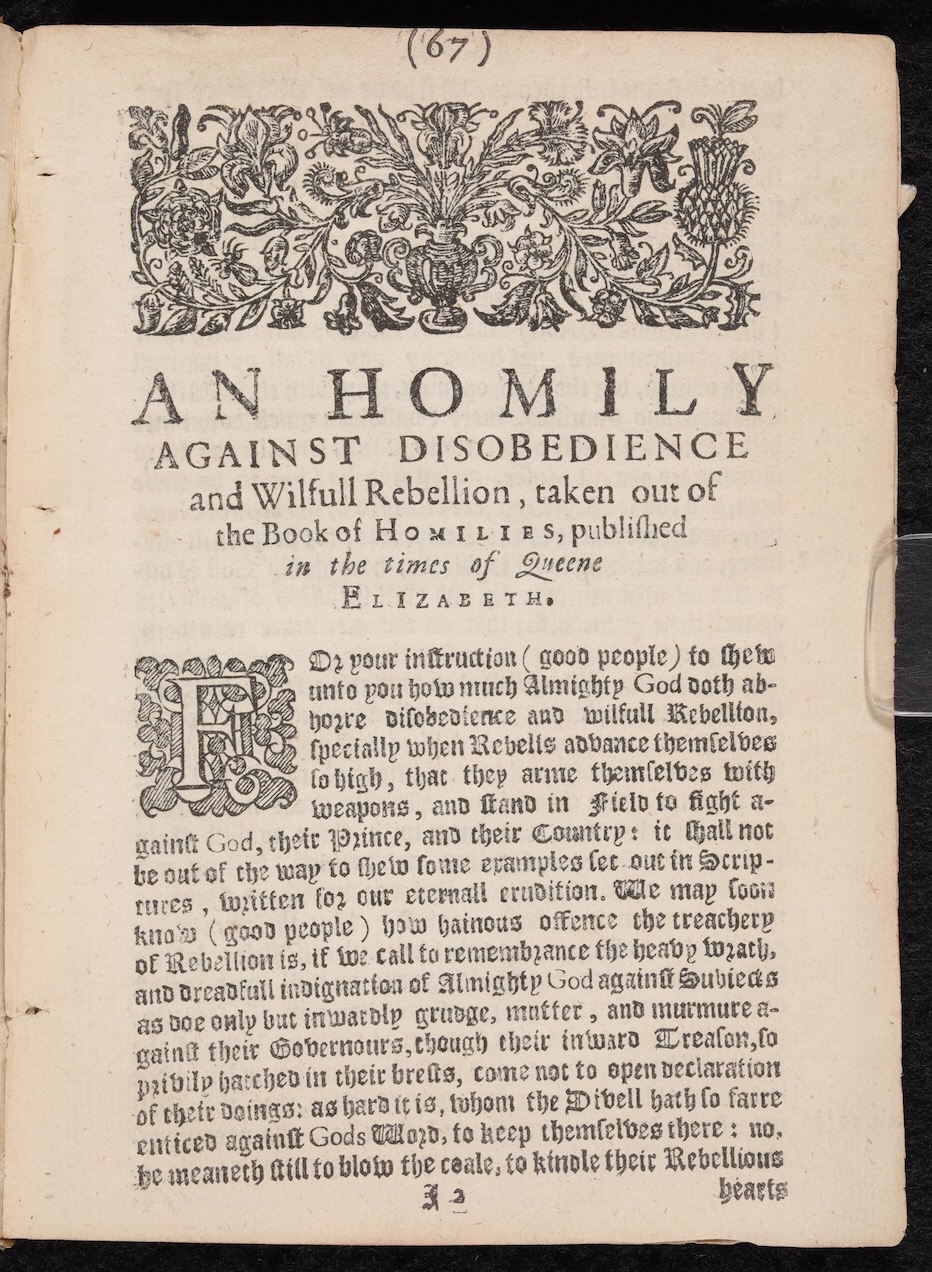

Prayers for Loyalty

The Church of England. A Forme of Common Prayer.

Oxford, 1643.

During the English Civil War (1642-1651), Books of Common Prayer (BCP) were banned by Parliament as they signaled Royalist sentiment as the king was the Head of the Church of England and many in Parliament wanted a revised, Puritan version of the BCP. Those found using a Book of Common Prayer were faced with a fine or even imprisonment. A Forme of Common Prayer explicitly states that rebellion against the Crown was impious. Forms of common prayer are sections of books of common prayer and are published separately. These tend to be special publications that can have special homilies or prayers for current events or to commemorate past events. The edition on display here includes a homily aimed at promoting loyalty to the king called “An Homily Against Disobedience and Wilfull Rebellion, taken out of the Book of Homilies published in the times of Queen Elizabeth”. This was published in Oxford while the king was on the run from Parliamentarian troops.

The Printing Revolution

Before William Shakespeare’s works could even be conceptualized in printed, Europe had to experience what is often called a printing revolution. Around 1440 in Mainz, Germany Johannes Gutenberg would change the course of history forever. Gutenberg, an inventor and craftsman, combined the use of molded movable metal type, a press, and printer’s ink to create what is known as the Gutenberg Printing Press.

A single movable-type printing press could produce up to 3,600 pages per day as compared to the few pages by hand-copying that could be completed in a day by an individual. By 1500, printing presses in Europe had produced 20 million volumes of work. Incredibly, during the sixteenth century alone, the output of the presses increased tenfold to an estimated 150 and 200 million copies.

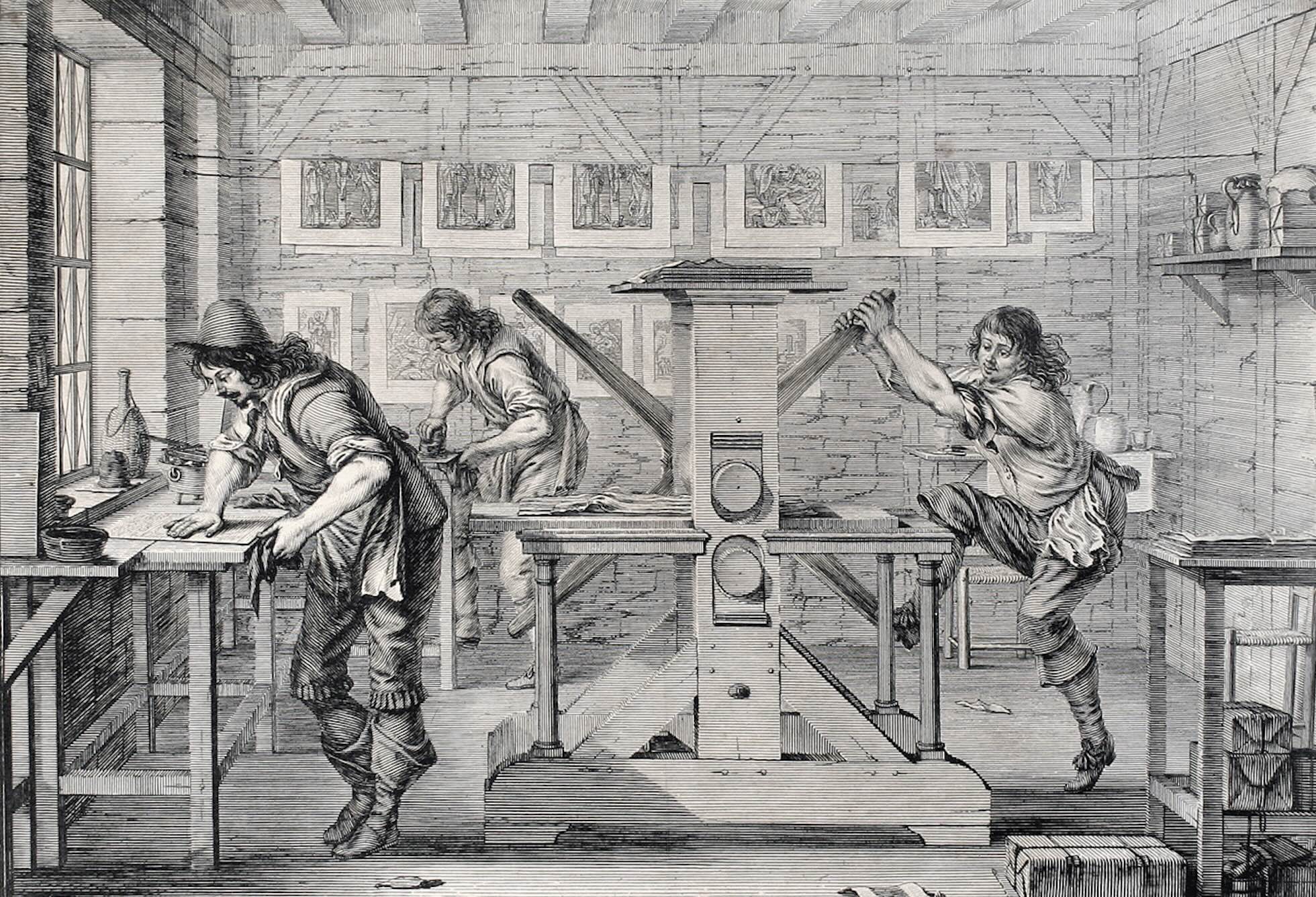

Printing was in many ways a new type of occupation that combined intellectual, physical, and administrative forms of labor and skills. The engravings on display here show that printing and bookmaking were operations that took many hands and required the unique skills of typefounders, compositors, correctors, pressmen, engravers, and s.

Example of Early Bookmaking Studio

Collaert, Jan. Nova Reperta. The Invention of Book Printing.

The Netherlands, 1589.

This engraving made around 1598 was part of a larger book entitled Nova Reperta, which detailed new inventions and trades emerging in Renaissance Europe, such as printing. In the background, a man prepares paper for printing in the press shown on the right. In the center, a young child lays out the newly printed paper for proofreading. On the left workers set type to be printed. In the 100 years since printing took over in Europe, the process largely remained unchanged by the late 1500s.

Inside a Print Studio

Bosse, Abraham. The Intaglio Printers.

London: Printed for G. Strahan, 1728.

This etching shows the final steps involved in printing. The person in the background inks the copper plate using a dabber, while in the foreground (left) another person wipes the plate with the palm of his hand. The third person on the right is pressing the plate, which is covered with a damp sheet of paper and a protective blanket. The person’s body position demonstrates the effort involved in turning the wheel of the press. In the text below the image, Bosse describes that the ink is made of burned nut oil and wine dregs, the best quality of which, comes from Germany.

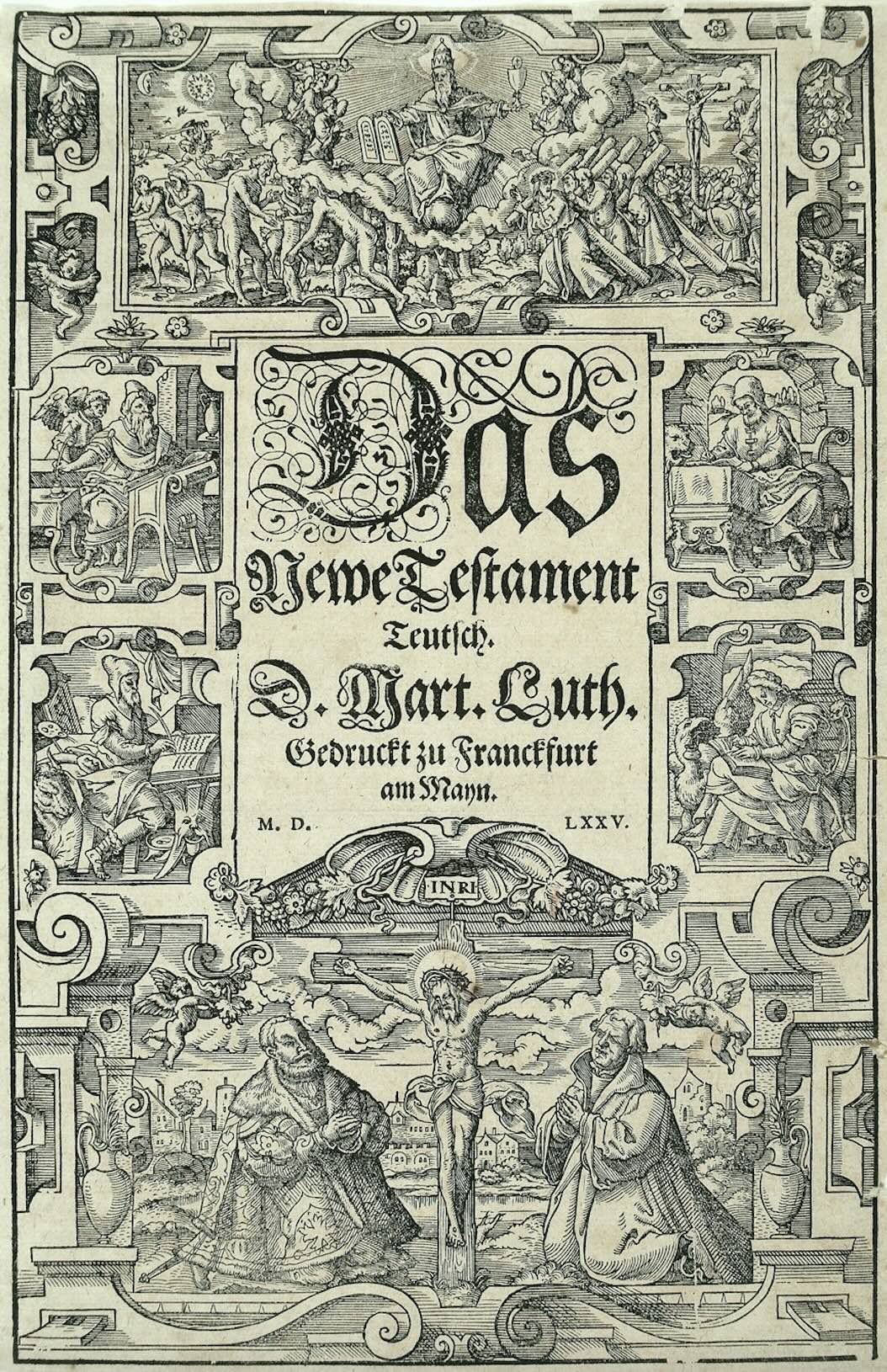

Martin Luther’s Influence

Das Newe Testament, Verdeudscht durch Doct. Martin Luther.

Wittenberg, Germany: Gedruckt Durch Hans Lufft, 1575.

Martin Luther anonymously published the New Testament in German in 1522. It also exposed readers to forms of the German language outside of their dialect. The title page of this edition depicts two men prostrate in prayer with Christ crucified in between them. The individual on the left is Frederick the Wise of Saxony and the man on the right is Martin Luther. The four images around the title are the four evangelists: Paul, John, Mark, and Matthew.

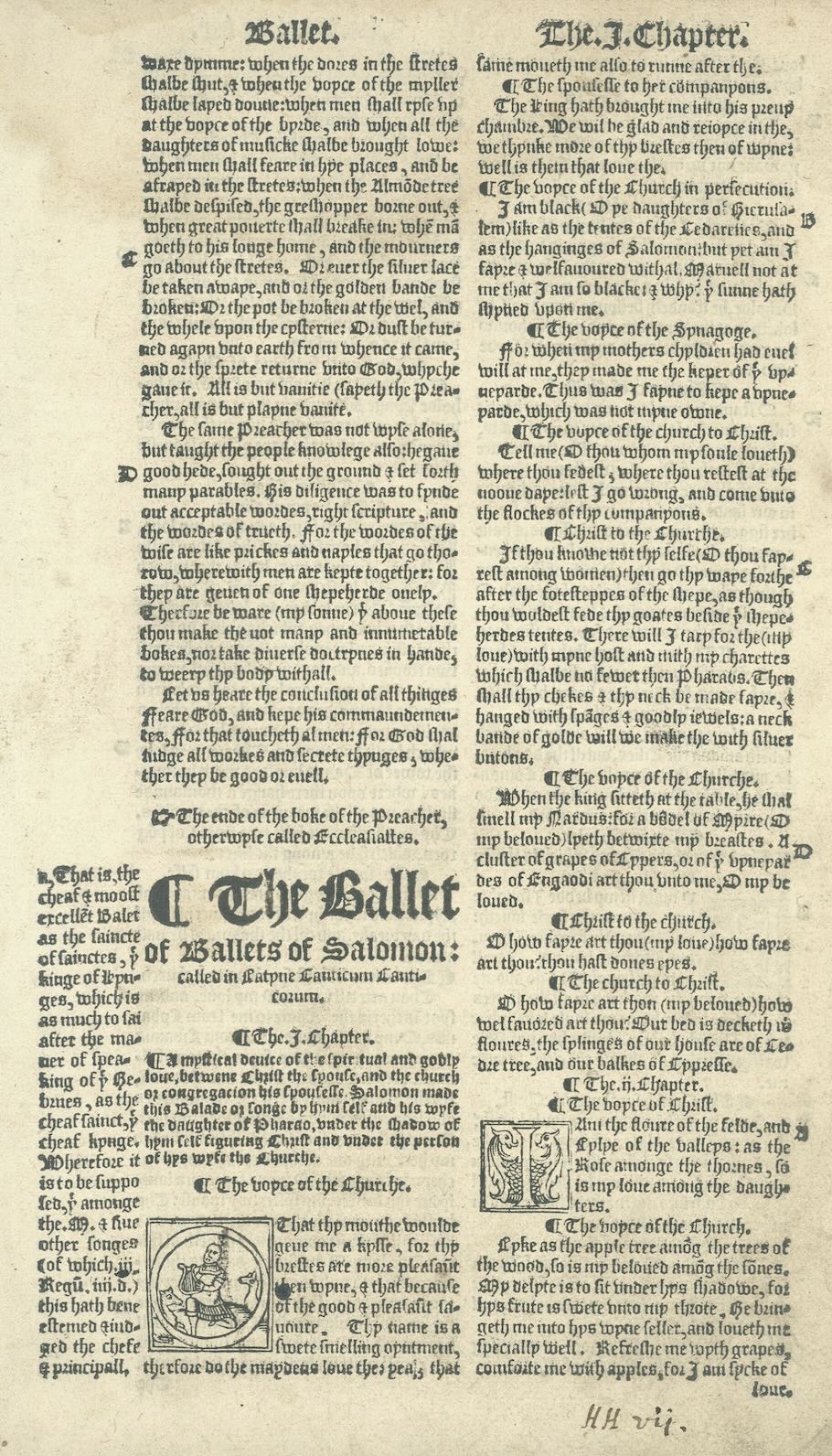

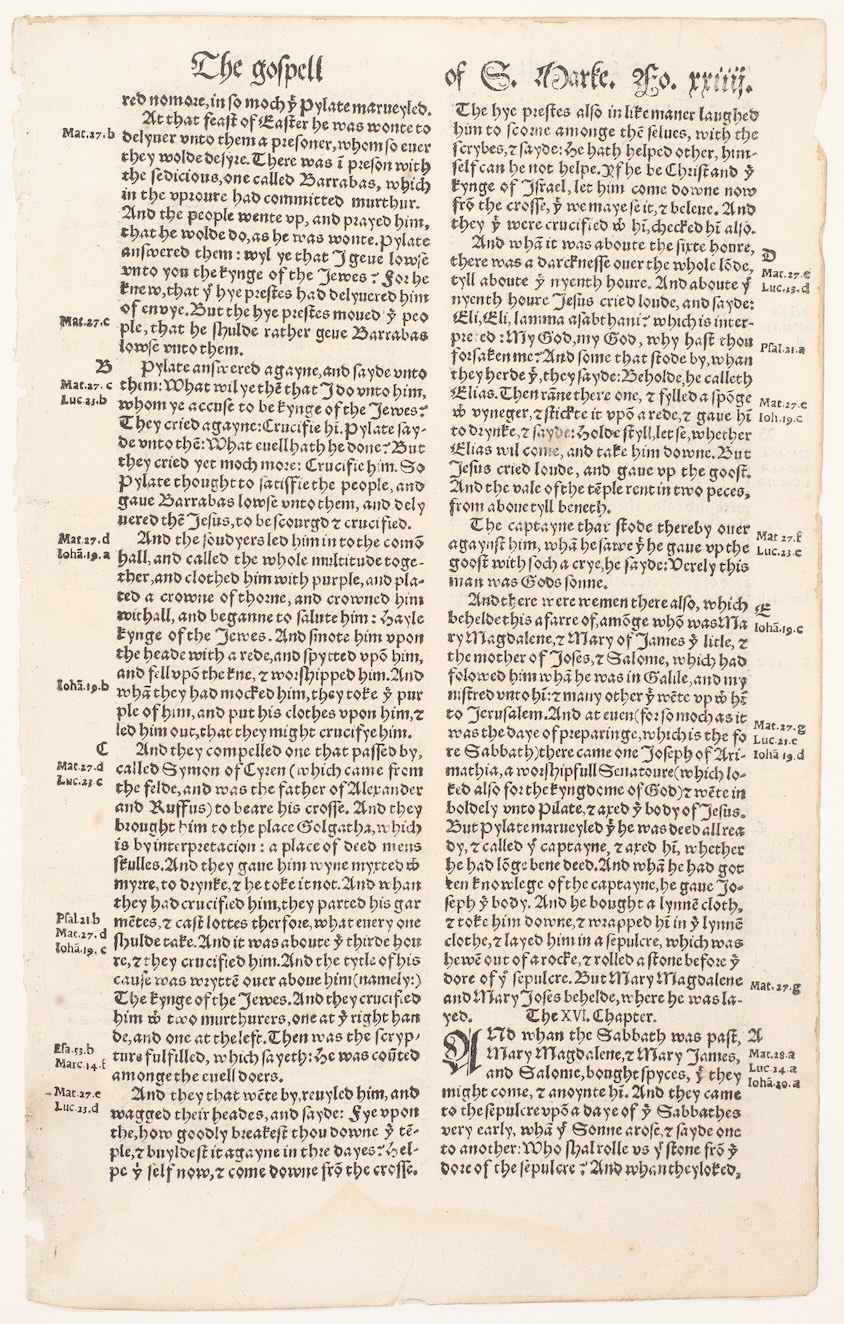

A Leaf from the Matthew Bible

The Byble that is to say all the holy Scripture: in which are contained the Olde and New Testamente. A leaf from the Matthew Bible.

London: John Daye and William Seres, 1549.

This leaf is from the Matthew Bible, compiled and translated by John Rogers, operating under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthew. This was the first complete English Bible translated from the original Greek and Hebrew rather than Latin. The translation takes much of Tyndale’s Old Testament, which heavily consulted Luther’s German Bible, Erasmus’ Latin version, and the Latin Vulgate Bible. The significance of the Matthew Bible for the English-printed Bible has been largely unrecognized, but it is foundational for future translations into English.

The Printed Word of God

Gutenberg’s first major project was printing an edition of the Latin Vulgate Bible between 1452 and 1455. In the first run, 180 copies were made using over 4,000 pieces of type, including individual letters, numbers, abbreviations, and punctuation. Of the original copies printed, 49 survive in at least a substantial portion and only 21 were complete.

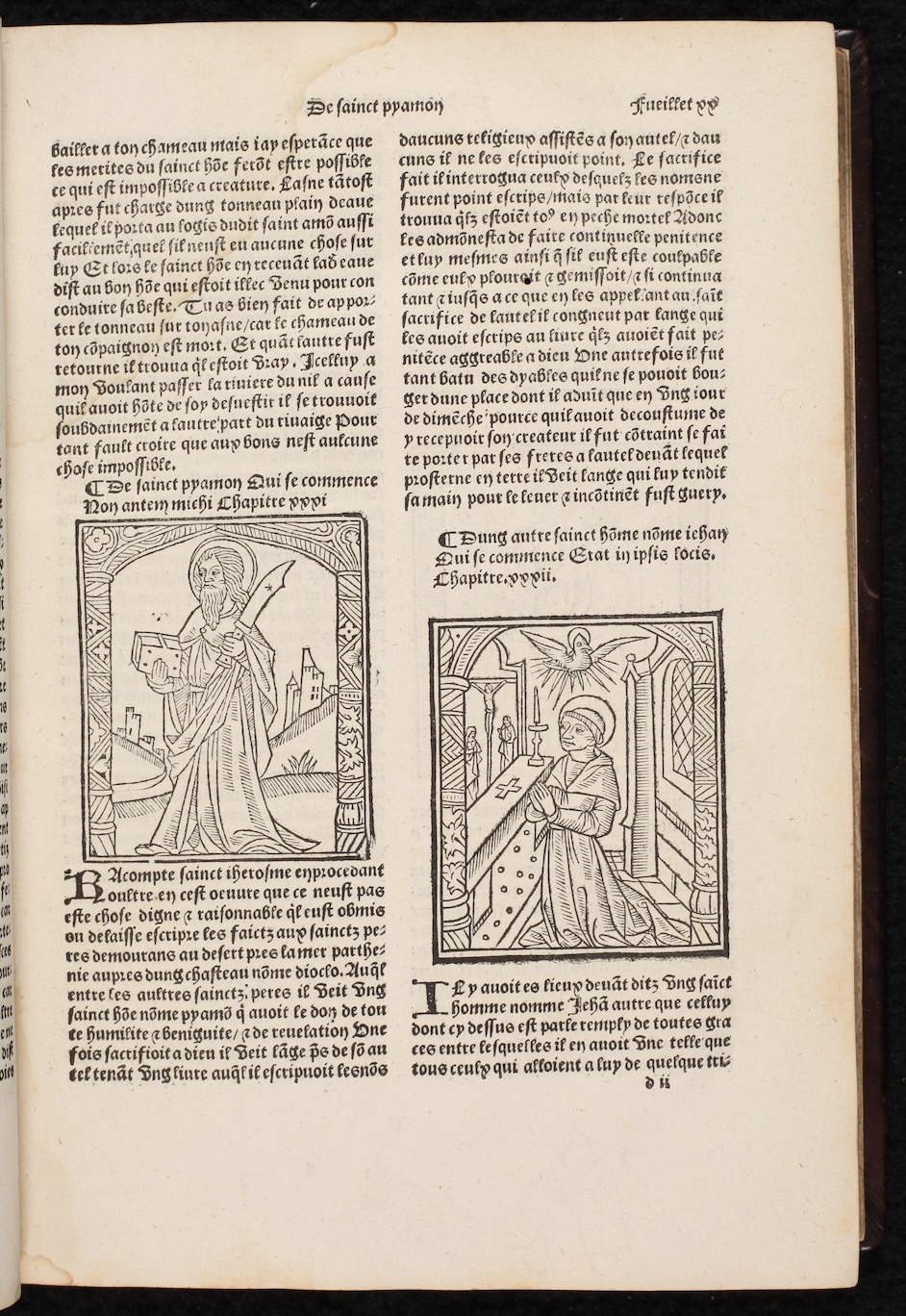

At this time, Latin was still the universal language of the Church, but the majority of lay people in Europe could not read Latin. By the turn of the sixteenth century, the demand for books in vernacular languages intensified, and indeed, the book market responded by publishing an ever-increasing number of translated texts. However, it was forbidden to translate the Bible into vernacular languages, so printers turned to other types of devotional texts to fill the demand.

One such type of text was hagiographies or stories about saints, which were extremely popular throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Printers translated and edited previously compiled hagiographies for the readers. For example, The Golden Legend, an encyclopedia of saints, was originally compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the thirteenth century and translated into every major European language.

Early Printed French Hagiography

La vie des anciens peres iadis demourans es grans desers degypte, thebayde, mesopotamie, et aultres lieux solitaires.

Paris: Pierre Le Dru, 1507.

Hagiographies, similar to the Golden Legend, were popular books to translate into the vernacular language at a time when Bible translations were still outlawed. Printed in both Latin and the common language, they were often decorated with woodcuts that provided a snapshot of the saint’s life being described in the text. This collection of hagiographies was printed in Paris by Pierre Le Dru who was active between 1488 and 1515. Many of the woodcuts in this edition are hand-colored to accompany the story of the saint.

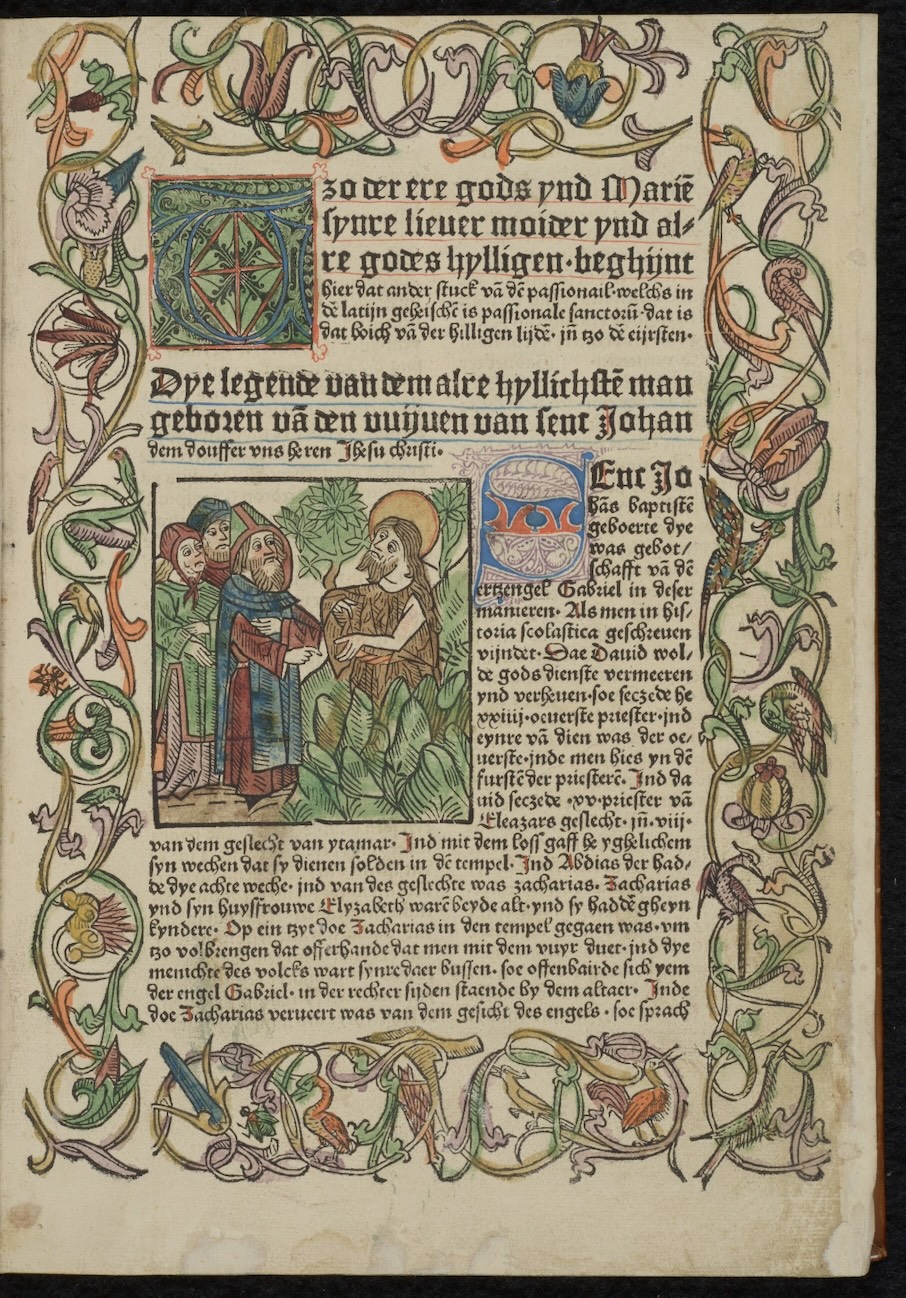

Early Printed German Hagiography

Voragine, Jacobus de. Dat duytsche passionail. 2 volumes.

Cologne: Ludwig con Renchen, 1485.

Dat duytsche passionail or The Golden Legend is a collection of 153 hagiographies or saints’ lives. These stories often describe the lives and miracles of saints. Not only was it a popular text for manuscripts, but among incunabula, or books printed before 1501, The Golden Legend was printed in more editions than the Bible. Most pages in this volume contain a woodcut with hand coloring that symbolized the saint whose life is being described in the text. Most images would be easily recognizable to a medieval or Renaissance reader.

Printing the Bible in English, but not in England

Wikgren, Allen Paul. A leaf from the first edition of the first complete Bible in English, the Coverdale Bible, 1535.

San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1974.

Myles Coverdale (1488-1569) printed his modern English translation of the complete Bible in 1535 and dedicated it to King Henry VIII. The later editions, both folio and quarto, published in 1537 were the first complete English Bibles printed in England. The Coverdale Bible is considered an indirect translation as it was largely taken from German and Latin translations of the Bible rather than the original languages.

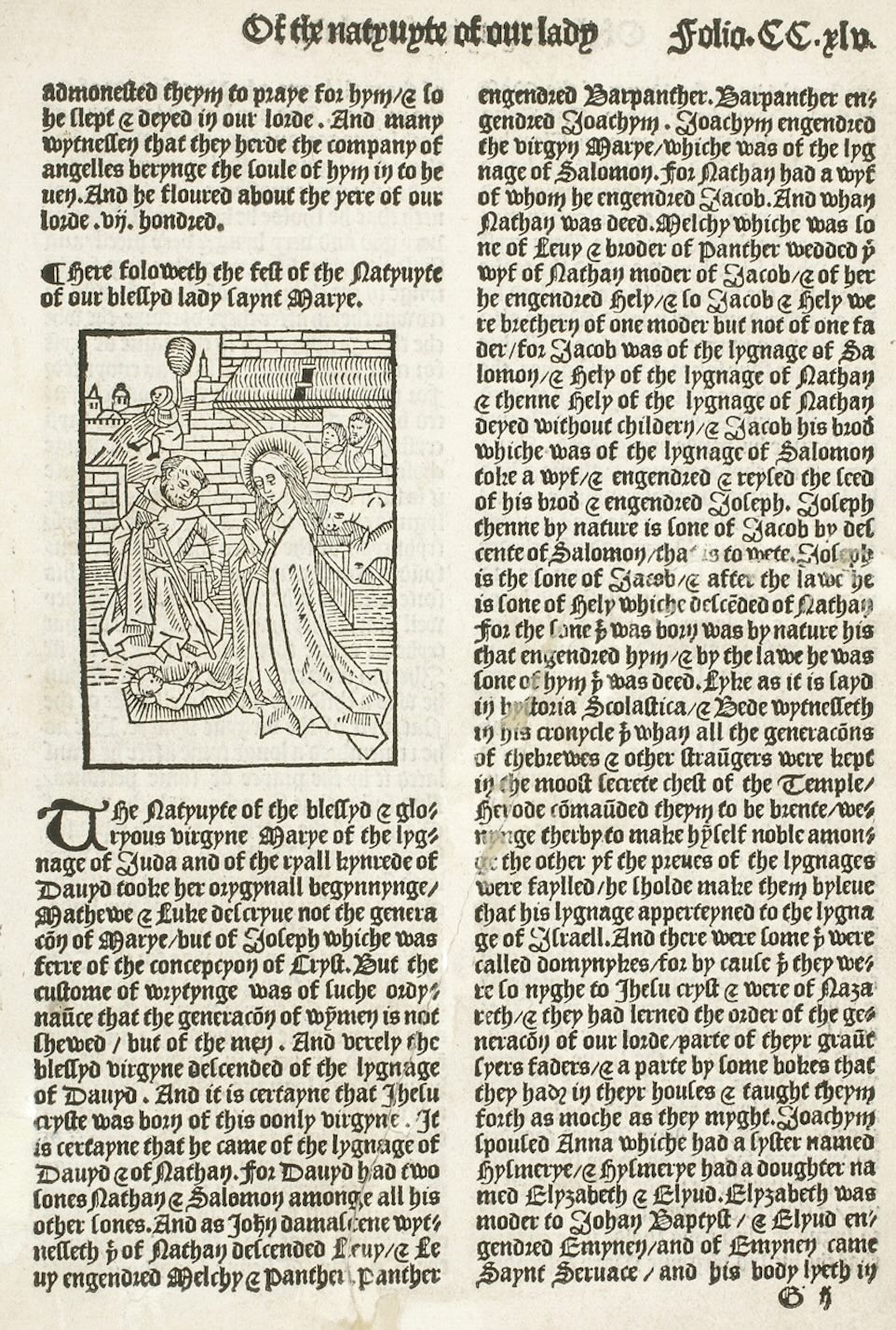

Early Printed English Hagiography

Voragine, Jacobus de. The Golden Legend.

London: Wynkyn de Worde, 1493.

The earliest surviving English translation of The Golden Legend dates to c.1438. In 1483, the work was re-translated and printed by William Caxton (1422-1491) and is considered the first text that Caxton printed in English. Caxton is credited with introducing the printing press to England in 1476. This edition was printed using Caxton’s translation by his assistant and predecessor, Wynkyn de Worde. Caxton’s translation, used here, included many additional saints that would appeal to an English or Irish reader.

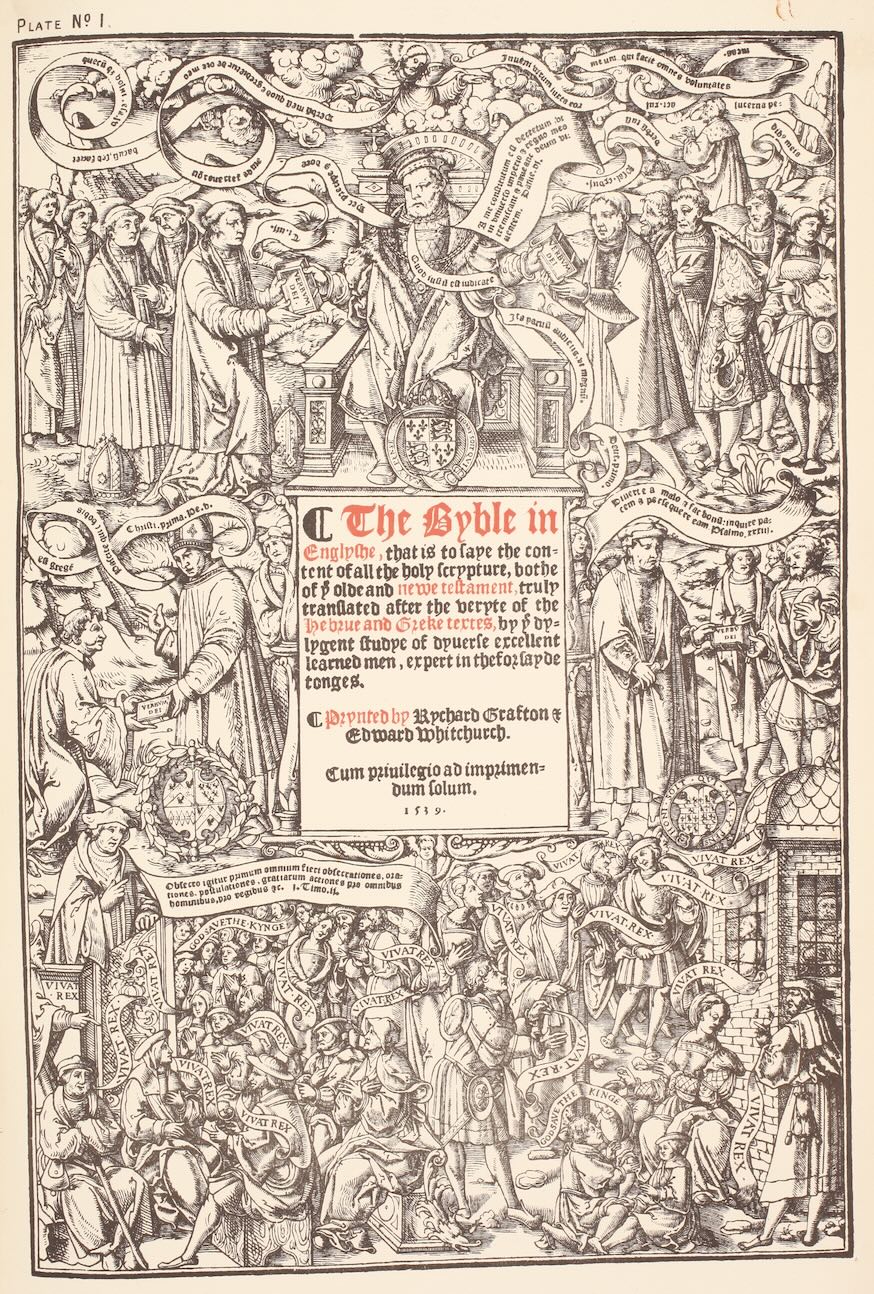

King Henry VIII’s Bible

A Description of the Great Bible, 1539, and the six editions of Cranmer’s Bible, 1540 and 1541.

London: Willis and Sotheran, 1865.

The Great Bible of 1539 was the first authorized edition of the Bible in English. King Henry VIII authorized it to be read aloud during Mass and other services of the Church of England. The Bible was prepared by Myles Coverdale under the supervision of the King’s Chief Minister, Thomas Cromwell. England was not yet equipped with printing presses that could handle the undertaking, so the first run of 2,500 copies was printed in Paris in 1539. On display here is a leaf from the 1539 and 1540 editions.

The King’s Reformer

Thèodore de Bèze Les vrais povrtraits des hommes illvstres en piete et doctrine […].

Geneva: Jean de Laon, 1581.

Thomas Cranmer displayed here was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and for a short time under Mary I. Cranmer supported the principle of royal supremacy, in which the king was considered sovereign over the Church within his realm and protector of his people from the abuses of Rome. As Archbishop of Canterbury, he established the first doctrinal and liturgical structures of the reformed Church of England and developed the Book of Common Prayer.

A Kingly Translation

A leaf from the King James Bible (1611)

London: Robert Barker, 1611.

The King James Version (KJV) is a Renaissance English translation of the Bible, specifically for the Church of England. One reason for the need for a new translation was a call from English Puritans who were unhappy with perceived problems in the Great Bible. King James also made changes, particularly when they did not align with the principles of divinely ordained royal supremacy. This is a single leaf, or page, from the first printing of the King James Bible in 1611. Within three years fourteen editions in various sizes were printed.

Monastics during the English Reformation

When Martin Luther (1483-1546) nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Church door in 1517, he could never have foreseen the rapid expansion of his ideas across Europe, but by the 1520s, Luther’s ideas spread to England. In 1527, Pope Clement VII denied King Henry VIII an annulment to his first wife, Queen Katherine of Aragon. Henry grew frustrated and turned to political methods for remedy.

The English Parliament, between 1529 and 1536, and with heavy royal encouragement, abolished papal authority in England and declared Henry VIII as Head of the Church of England. This allowed the king to approve his divorce and marry Anne Boleyn, his second wife in the hopes of getting a male heir.

Three important acts of Parliament were issued during the Reformation Parliament that would forever change the course of British history.

- The Act of Succession: recognized the validity of the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and denied his previous children a claim to the throne.

- The Act of Supremacy: acknowledged the king as Supreme Head of the Church, below only to God.

- The Treason Act: enforced denying the king’s title in the previous acts as treasonous and punishable by death.

All the king’s subjects, including all who had sworn monastic vows, were required to swear oaths to the Acts of Succession and Supremacy, thus denying their affiliation to the pope’s authority.

Those who refused to swear the oath were executed for treason by the king, including many monastics who were imprisoned and executed by the king. Even those in top positions in Henry VIII’s government were not immune. Sir Thomas More, Henry’s Lord Chancellor, was arrested and executed for refusing to swear the oath of succession. He was later beatified, along with 53 other English Reformation martyrs on 29 December 1886 by Pope Leo XIII.

In Defense of a United Catholic Church

Reginaldi Poli Cardinalis Britanni, Ad Henricum. Pro ecclesiasticae unitatis defensione.

Rome: 1538.

Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500-1558) was a prominent opponent of Henry VIII’s break with the Roman Catholic Church in 1532. He fled to Italy after refusing to swear the oath of succession and composed this treatise while there. The text is a scathing attack on Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, the soon-to-be second wife of the king. It concluded by arguing that Henry VIII should repent for his sins. Cardinal Pole spent much of his life in exile and was only allowed to return to England in November 1554. He died in 1558, almost 12 hours after the death of the last Catholic queen of England: Mary I.

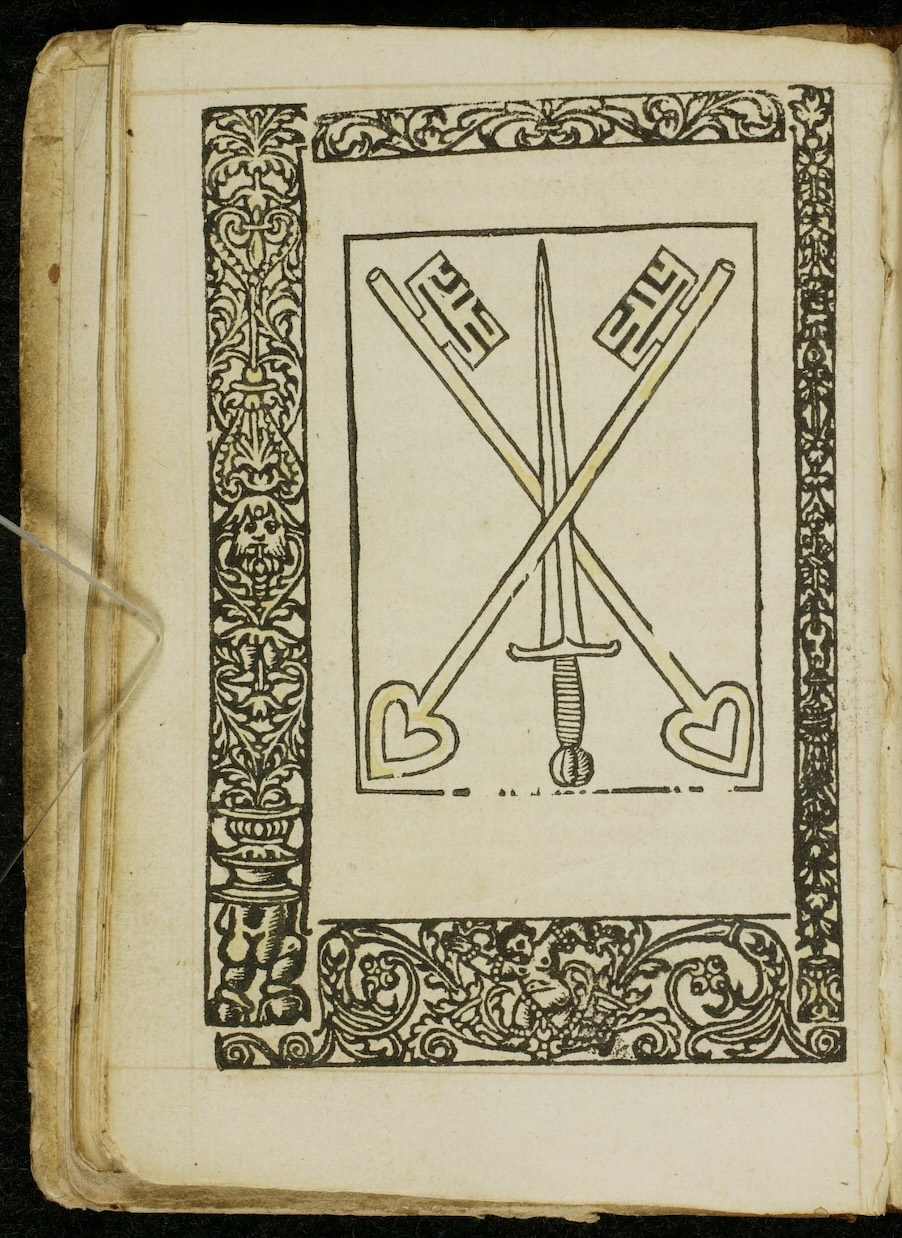

Pocket-Sized Rule of Saint Benedict

Benedict, Abbot of Monte Cassino. Regula b. patris Benedicti a b. Dunstano diligenter recognita, cum plusculis alijs a tergo huius explicandis.

Paris: Thielmann Kerver, 1544.

This is an example of an early, pocket-sized, printed Rule of Saint Benedict. It was printed by Yolande Bonhomme, one of a handful of women printers working in Paris in the sixteenth century. Her father and husband were both successful printers, but when her husband died young in 1522, she assumed control of his printing shop and continued to print under his name. She is estimated to have printed anywhere between 140 and 200 books before she died in 1557. She became the first woman to print a Bible in Europe, and many of her publications were devotional in nature. The edition is ornate with woodcut borders on every page, the printer’s symbol on the title and final pages, and a full-page woodcut of crossed keys and a sword, which is on display here. The keys symbolize St. Peter who was given the keys to the Church and St. Paul symbolized with the sword representing his martyrdom.

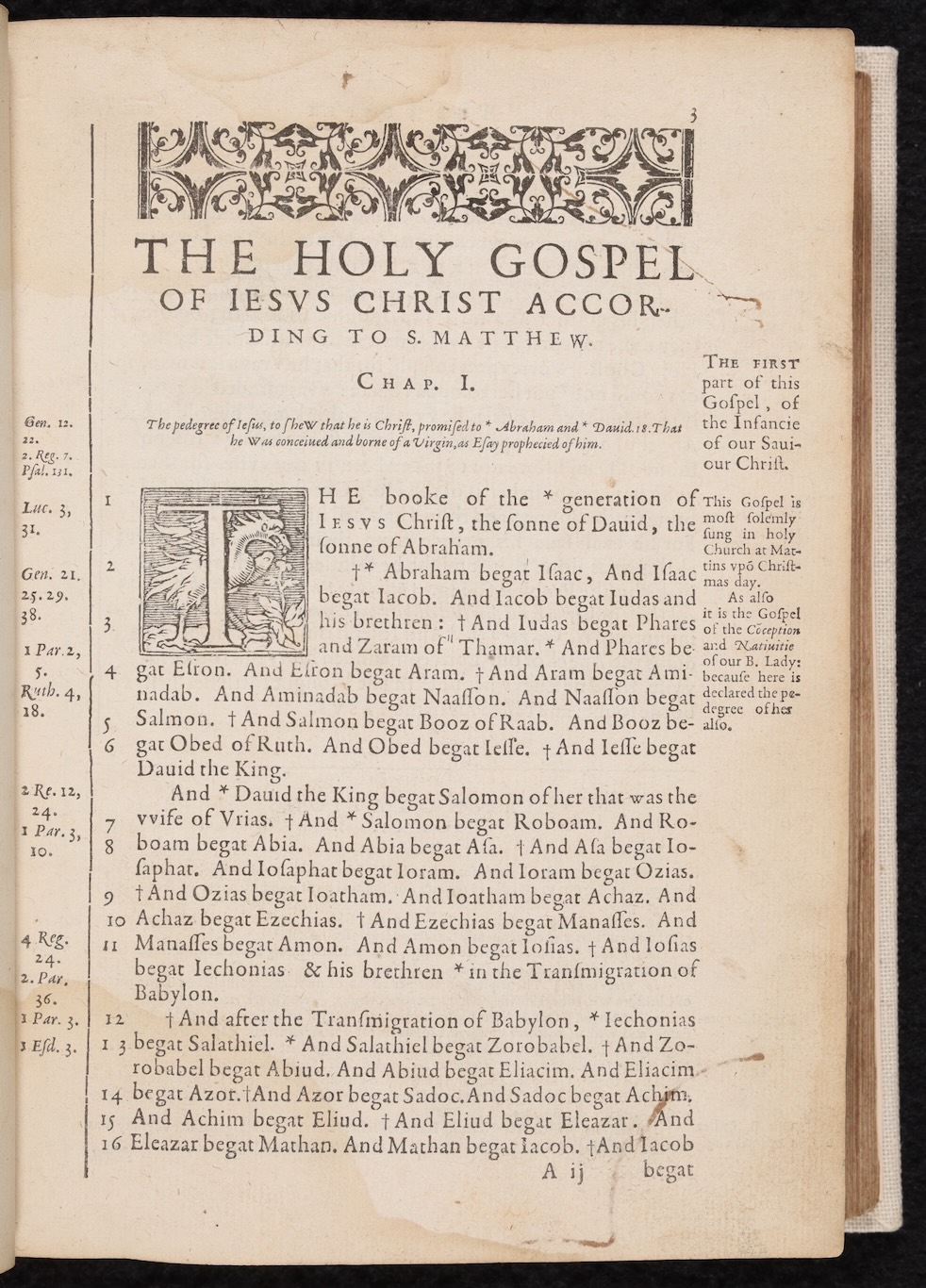

First edition of the Rheims New Testament

The Nevv Testament of Iesvs Christ: translated faithfvlly into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same …

Reims: Jean de Foigny, 1582.

Under Queen Elizabeth I, many English Catholics fled England for safe refuge in more Catholic-leaning regions in Europe. Small communities of English Catholics formed in places like France. For example, an English college for the education of exiled English Catholics was established in 1568 by Jesuits as part of the University of Douai, in modern-day France. By the late 1500s, Roman Catholics did not have an English version of the Bible. Therefore, a translation project was proposed by William Allen (1532-1594), an English cardinal and exile, who spearheaded the undertaking. The purpose of the project was to uphold Catholic values and tradition in the face of the Protestant Reformation.

They began with the New Testament, which was printed in 1582 and the Old Testament followed in 1609/10. The combined translations of the Old and New Testaments are often referred to as the Douay-Rheims edition, although they were initially published separately as shown here with the first editions. This is the first English Bible translation intended specifically for Roman Catholics and was outlawed in England for over a century.

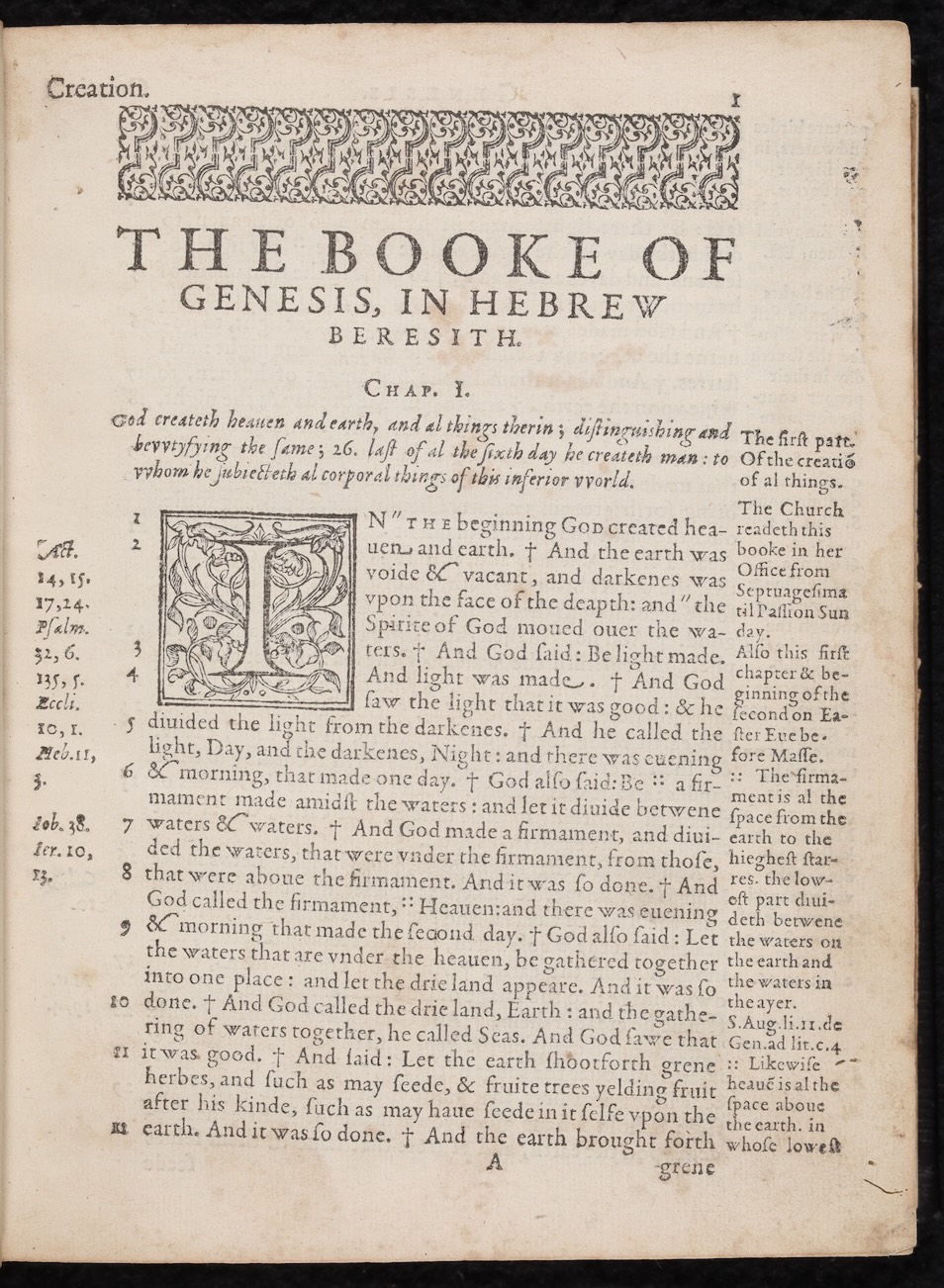

First Edition of the Douay Old Testament

The Holie Bible faithfully translated into English, out of the authentical Latin, Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greeke, and other editions in divers languages.

Douai: Laurence Kellam, 1609-1610

The English Reformation & Books of Common Prayer

King Henry VIII broke away from the Pope’s authority in 1534 and established the Church of England, later known as the Anglican Church. This brought uncertainty about belief and doctrine to many people, particularly how to carry out Mass, the sacraments, and ceremonies. To rectify this, England’s top church official, Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of Canterbury, created a uniquely English liturgy under Henry VIII, which became more radically Protestant under Edward VI, Henry’s son and heir. Cranmer’s work ultimately became the first prayer book, the Book of Common Prayer (BCP), published in 1549 for the Church of England.

The Book of Common Prayer is the name of several related prayer books used in the Anglican Church. The first edition printed in 1539 was the first prayer book that had provisions for the daily offices (morning and evening prayer), scripture readings for Sundays and holy days, and services for Communion, public baptism, confirmation, matrimony, visitation of the sick, burial, purification of women after childbirth, and Ash Wednesday. The publication was largely meant to ensure uniformity across parishes by church officials.

These editions from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (1637, 1639, 1662, 1687, 1727) demonstrate the refinement and shifts under each monarch as they assumed their role as Head of the Anglican Church.

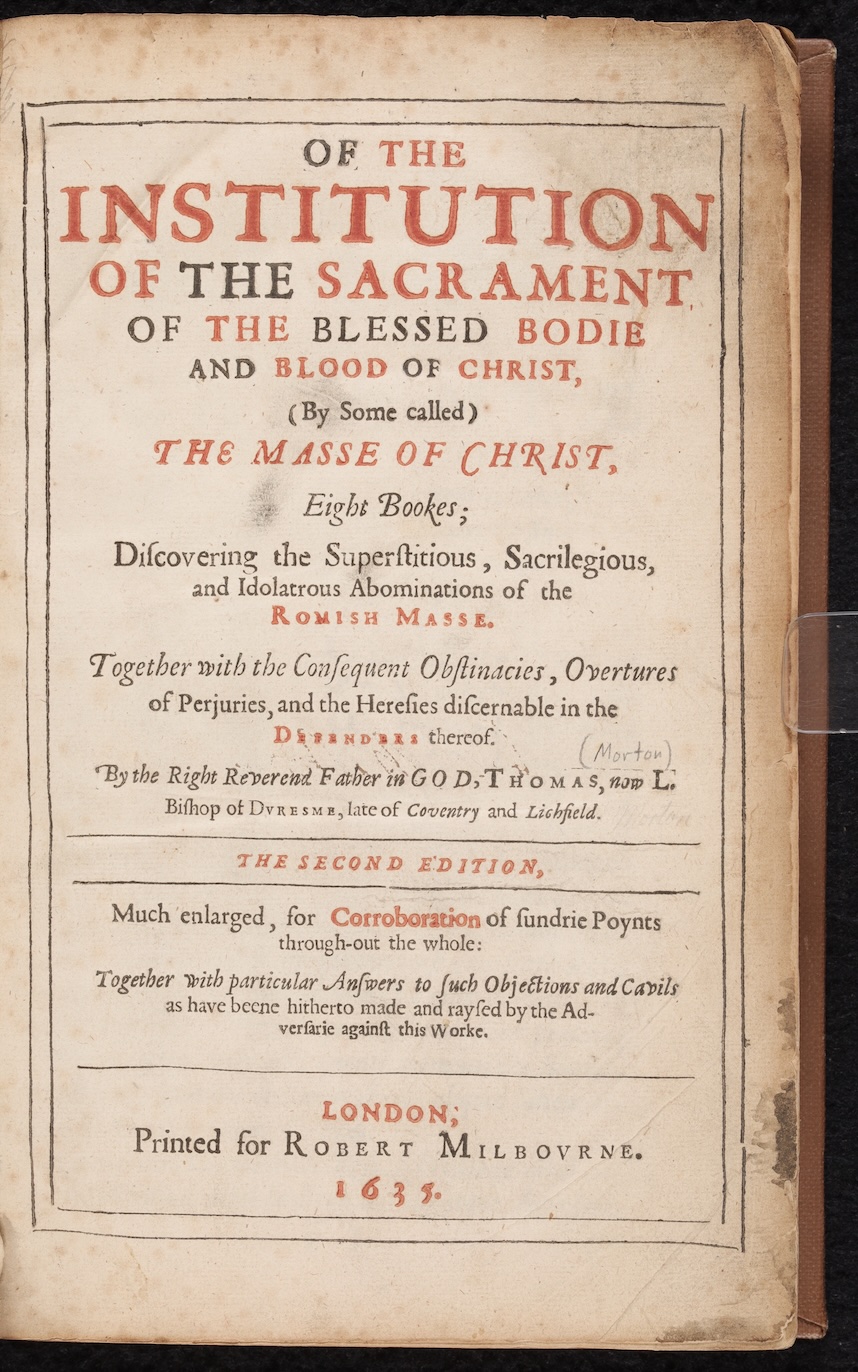

Reformer’s Comments on Catholic Mass

Of the institution of the sacrament of the blessed Bodie and Blood of Christ (by some called) the Masse of Christ.

London, Augustine Mathewes, 1635.

Written over 100 years after the beginning of the Protestant Reformation, this volume discusses the doctrine and belief surrounding the Roman Catholic Mass. It was written by an English Protestant in the form of questions and answers. Through the dialogue format, it is claimed that Catholic Mass was superstitious, idolatrous, and sacrilegious in the eyes of Protestants. The page open is “an advertisement” directly speaking to English Roman Catholics. The first line reads “[t]o all Romish Priests, and Jesuites of the English Seminaries…”.

The Book That Started a War

The Booke of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments. And other parts of divine Service for the use of the Church of Scotland.

Edinburgh: Robert Young, 1637.

On Sunday, July 23, 1637, King Charles I of England tried to implement a new prayer book for the Church of Scotland that aligned with the practices of the Church of England. It was immediately met with multiple rebellions and riots across Scotland, with the most famous being Jenny Geddes who threw a wooden stool at the Bishop of Edinburgh during mass at St. Giles’ Cathedral. The series of protests was successful, and the 1637 prayer book for the Church of Scotland was rejected and abandoned.

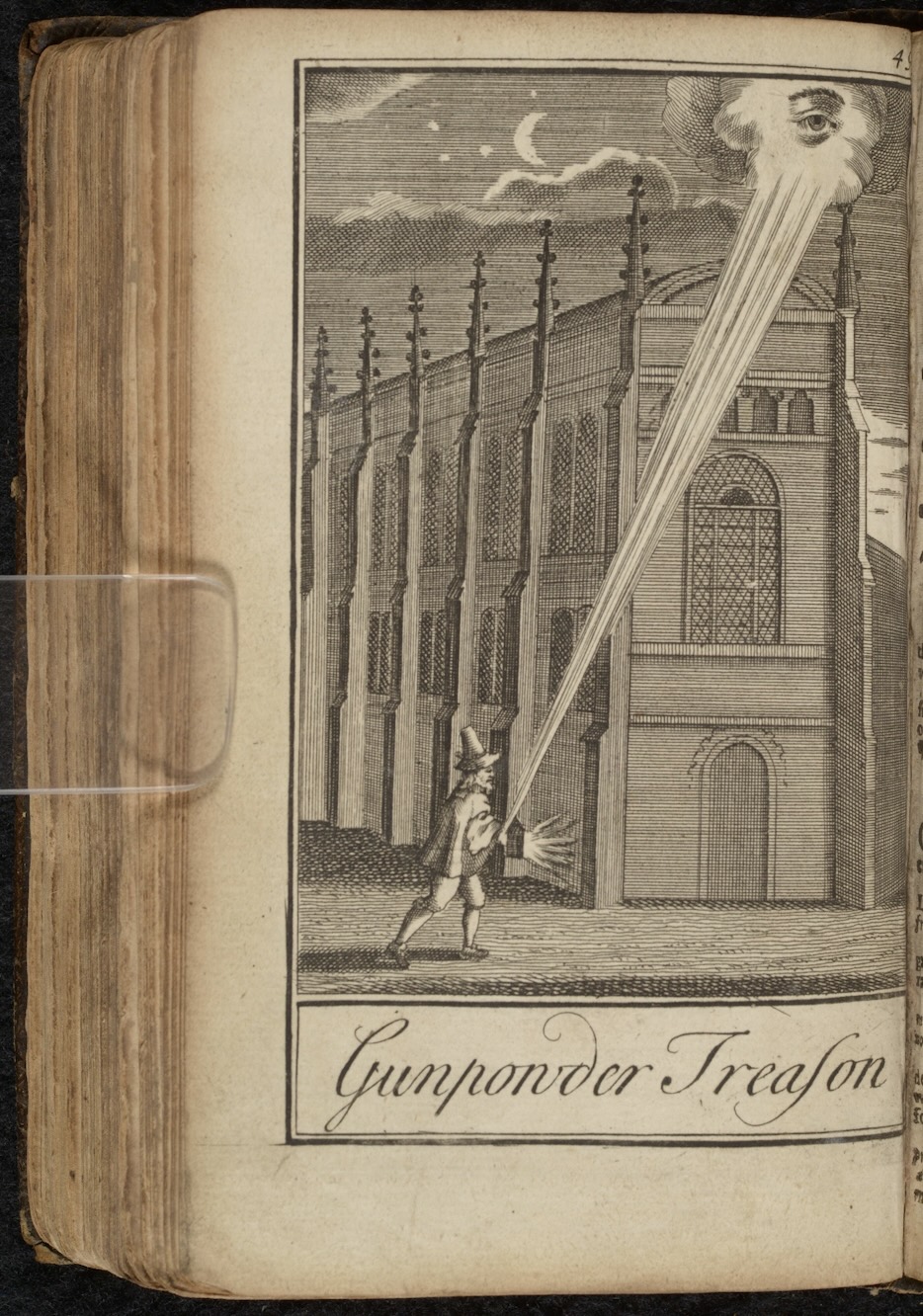

Remember, Remember the 5th of November

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacrament and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church.

Oxford: John Baskett, 1727.

It was not uncommon for Books of Common Prayer to contain prayers for past or current events. On display here, is the beginning prayer for the safe deliverance of King James I from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, which set out to blow up Parliament and the King on November 5th. The plot was led by a group of English Roman Catholics, including the infamous, Guy Fawkes, in the hopes of removing many Protestants in power. The plot was uncovered, and the conspirators were arrested and executed for treason.

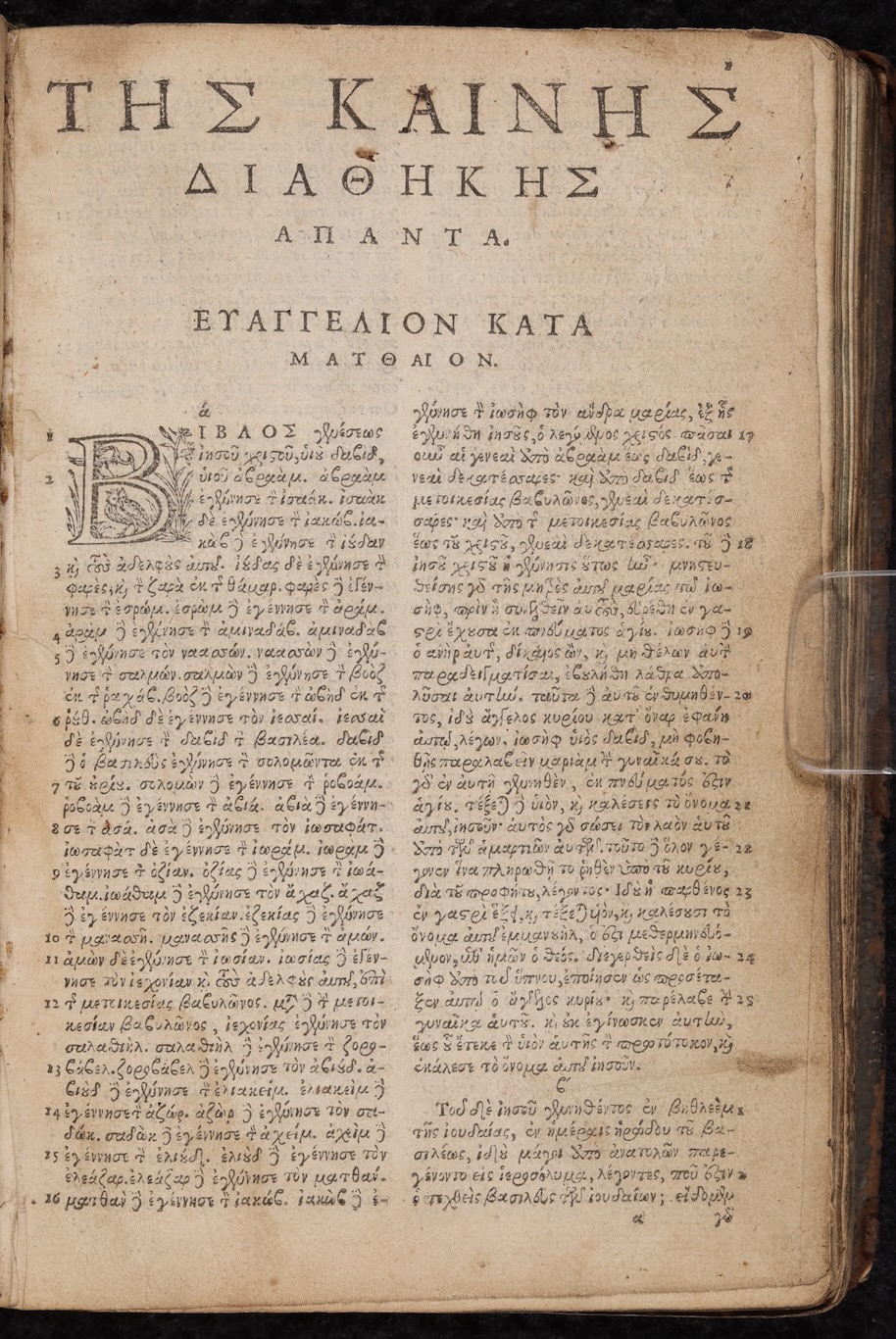

A Multi-Lingual Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacrament and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church.

London: Robert Barker, 1639.

The Book of Common Prayer could also be personalized to some extent. This edition, which is a small personal-sized volume, includes the Gospels in Greek (“Tes Kaines Diathekes Apanta Euaggelion kata Mathaion”), followed by a section beginning with Veni Creator Spiritus (“Come, Creator Spirit”), in English and set to music. The gospels in Greek are not normally found in books of common prayer, and it might indicate a special volume for an individual who was interested in Greek.

Individual-Sized Bible

The Holy Bible, Containing the Bookes of the Old Testament and the New.

London: Henry Hills and John Field, 1660.

This was the third English translation of the Bible to be approved by English Church authorities. This edition uses the King James translation that Hills and Field state they purchased the original manuscript of the translation from the heirs of Robert Baker (printer of the first edition of the KJV) for £1200 ($2.6 million today). The original King James Bible manuscript most likely burned in the Great Fire of London in 1666. Hills and Field printed many Bible editions and sizes, including this small personal-sized Bible that contains handwritten notes from previous owners.

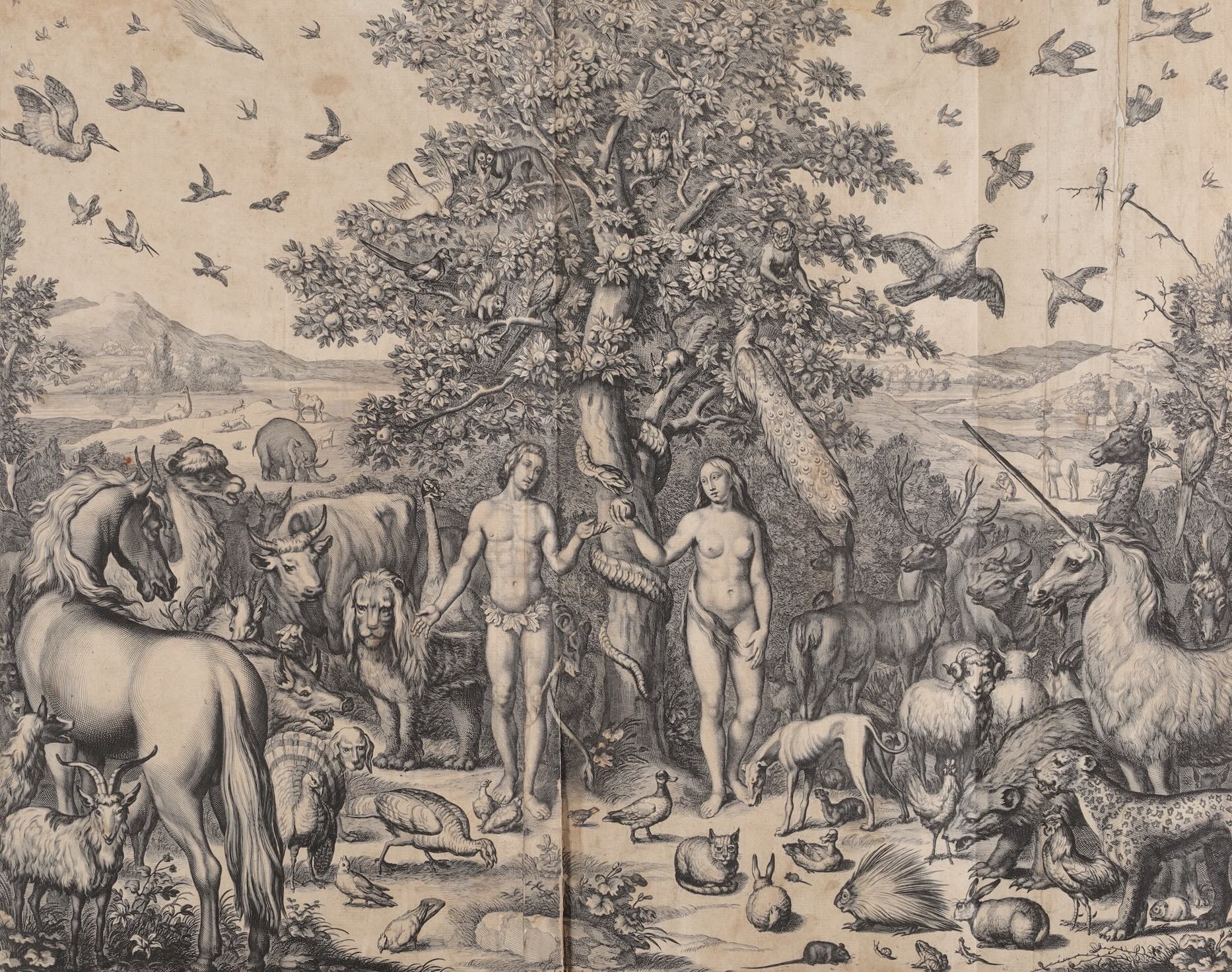

Large, Expensive Bible

The Holy Bible: Contayning the Old and New Testaments, newly translated out of ye originall tongues, and with ye former translations diligently compared and revised.

London: John Field, 1657.

This is a rare edition of the King James Bible printed during the Interregnum period (1649-1660) between the execution of King Charles I and the return of his exiled son, Charles II, to the British throne. During this time, Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector, established the Commonwealth of England, while maintaining a large portion of the power vacuum left after the king’s execution. Cromwell gave Field and Hills a monopoly on the Bible market giving them the only official license to print the Bible. The image on display is Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden before the Fall.

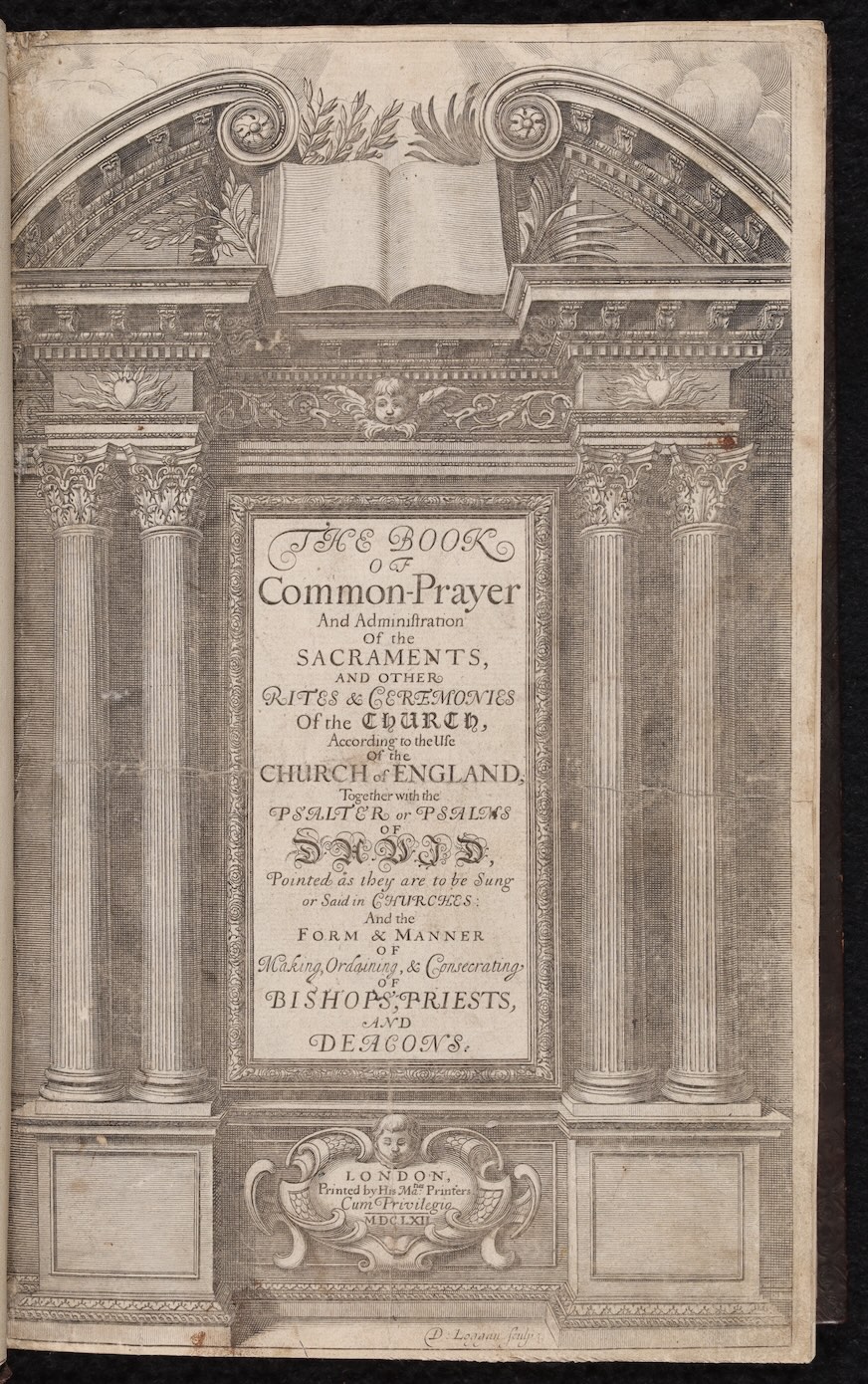

Official Version for the Church of England

Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Church of England.

London, 1662.

The 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the authorized liturgical book for the Church of England and other Anglican bodies around the world. This edition has been in continued print and regular use for over 360 years. This edition alongside the King James Bible had a profound influence on the development of the English language. This is the first BCP printed after the Restoration of King Charles II following the English Civil War and Interregnum period. This edition was largely revised because English Puritans were unhappy with earlier editions.

Large Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Church of England.

London, 1687.

This is a later and larger edition of the Book of Common Prayer printed in 1687 under the Catholic king, James II. It was published in the same year that James II issued the Declaration of Indulgence, which suspended laws that required people to conform to the Church of England. It also allowed people to worship in their homes and removed the requirement to take a religious oath for government jobs. It did not last long as James II was deposed and replaced by his daughter, Mary II, and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange.

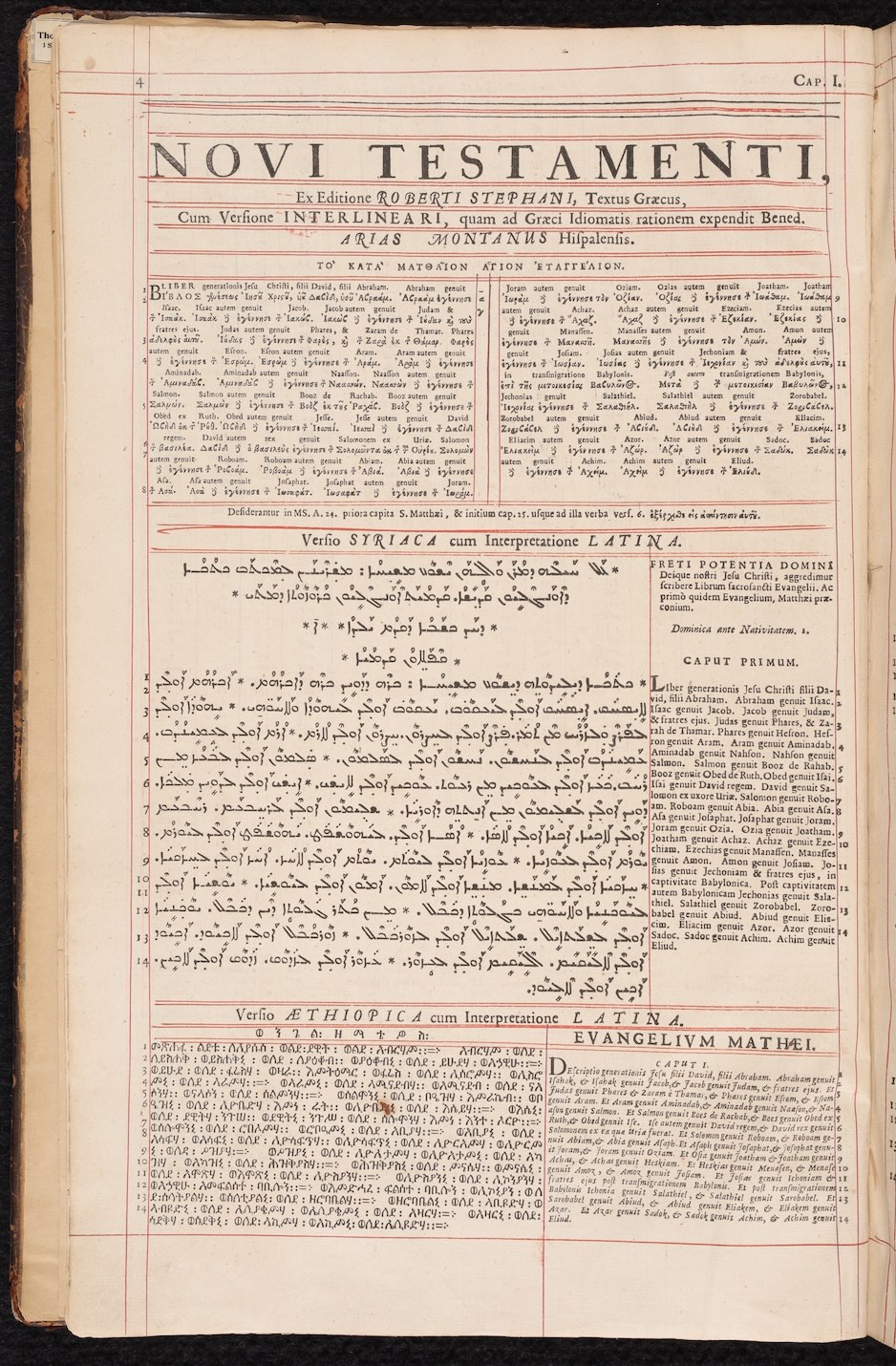

Bibles and Interest in Original Languages

Humanism, which encouraged the study of classical languages and societies, was a fundamental part of the European Renaissance. It cultivated a desire for the most accurate Biblical translations derived from original languages rather than relying on indirect translations from Latin. Polyglot Bibles were editions of the Bible that displayed multiple languages side-by-side. These are considered among the most impressively printed and edited intellectual endeavors in Renaissance Europe.

Two of the six volumes of the London Polyglot Bible are on display here. This edition was the most ambitious edition to date with nine languages featured. The New Testament texts include Latin, Greek, Syriac, Arabic, Persian, and Ethiopic, while the Old Testament has Hebrew and Samaritan in place of the Syriac and Ethiopic.

Not only were these multi-lingual side-by-side translations an intellectual feat for the time, but the typesetting, editing, and printing of such complex and varying letters and alphabets was a mammoth undertaking.

There are considered four “great” polyglot Bibles printed in the Renaissance: the Complutensian (Spain, 1514-17), Antwerp (1569-72), Paris (1628-45), and London (1654-57). In the words of the London Polyglot Bible’s editor, Brian Walton, these volumes together make “the truest glasses to represent the sense of reading” of Scripture.

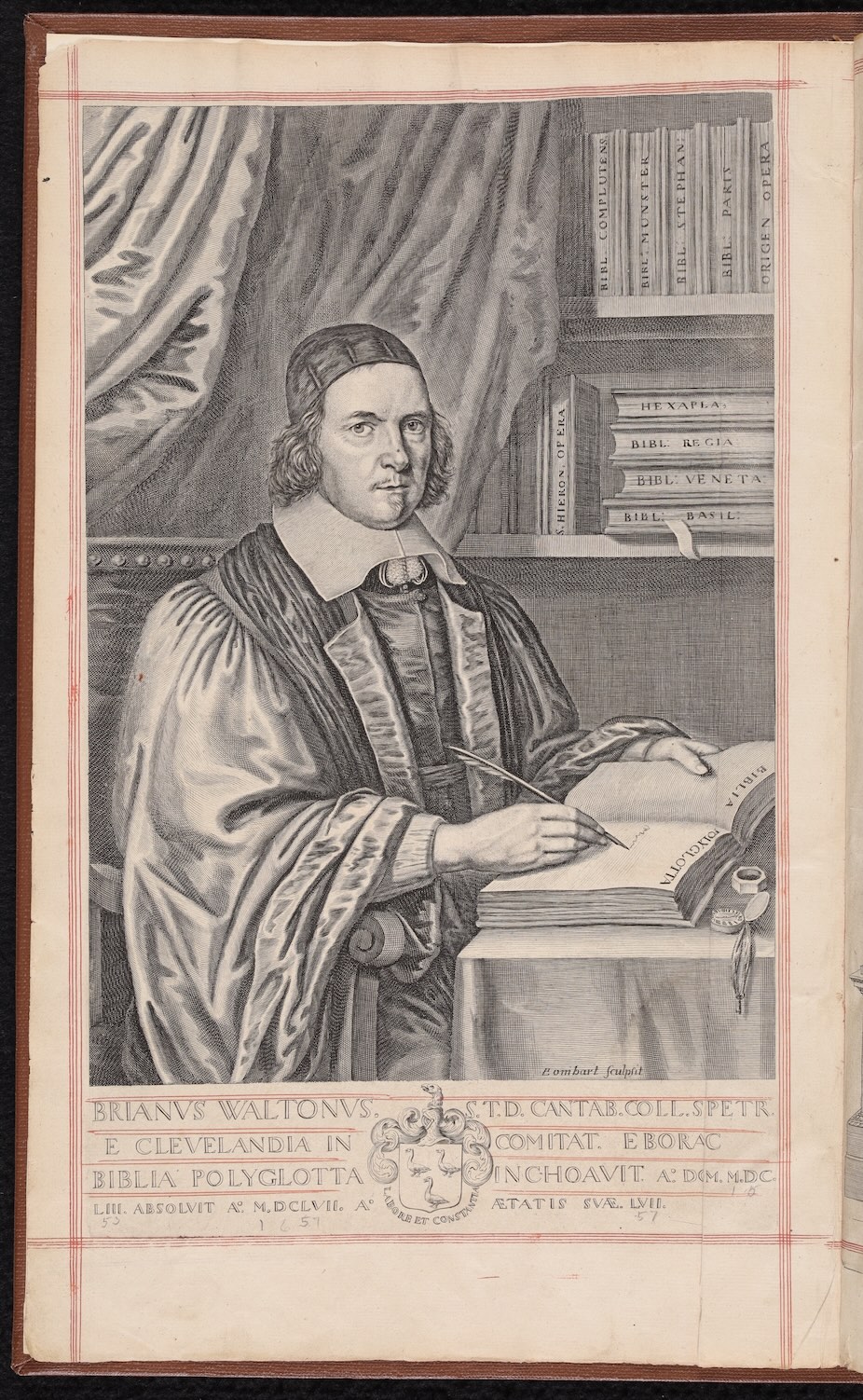

Bible in All the Original Languages

Biblia sacra polyglotta: complectentia textus originales, Hebraicum, cum Pentateucho Samaritano, Chaldaicum, Græcum. Versionumque antiquarum, Samaritanae Græcum LXXII Interp., Chaldaicæ, Syriacæ, Arabicæ, Æthiopicæ, Persicæ, Vulg. Lat. Quicquid comparari poterat. 6 volumes. Volume 1.

London: Thomas Roycroft, 1657.

The great polyglots represented the major intellectual and cultural trends of the day. From humanism came the desire to create the most accurate biblical text possible in its original languages, from the Reformation came the impetus to evangelize and unite Christendom using the Bible, from increasing cultural exchanges with the Ottoman empire came the interest in Near Eastern languages, and from print culture came the resolution that all this could be accomplished through the printed word. Polyglots united all these strands of cultural history in the service of religion, and the work behind them went on to fundamentally shape intellectual culture for centuries. In the words of the London Polyglot Bible’s editor, Brian Walton, these volumes together make “the truest glasses to represent the sense of reading” of Scripture.

The large, engraved portrait of the London polyglot’s translator and editor, Brain Walton, opposite the title page, depicts him as an ecclesiastical intellectual in bishop’s robes, quill in his hand, and surrounded by books. He is actively writing in the open book with his quill and open ink pot with scribbles shown on the open pages. The title of the text is revealed at the top of its page as the Biblia Polyglota. Moreover, the title page is rich with symbolism that people in the 17th century would easily recognize. On the bottom columns are scenes of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and Noah with his boat. The four symbols of the four evangelists (winged angel, lion, ox, and eagle) are towards the top of the columns with scenes from the Nativity, Last Supper, Crucifixion, and Resurrection shown behind the four evangelists. The men in the middle of the engraving are important Old Testament figures, such as Moses, Eziekiel, and Aaron. At the top of the arch sits St. Peter and St. Paul.

Bible in the All the Original Languages

Biblia sacra polyglotta: complectentia textus originales, Hebraicum, cum Pentateucho Samaritano, Chaldaicum, Græcum. Versionumque antiquarum, Samaritanae Græcum LXXII Interp., Chaldaicæ, Syriacæ, Arabicæ, Æthiopicæ, Persicæ, Vulg. Lat. Quicquid comparari poterat. Volume 5 of 6.

London: Thomas Roycroft, 1657.

Many of the languages that appear in polyglot had rarely, if ever, been printed before. This forced early polyglot scholars to find printers skilled enough to make new print types from scratch, often using manuscript sources. In doing so, it was hoped readers would study the Bible in all the languages presented in the volumes, but recognized the fact that few Europeans, even educated ones, were able to do so. Care was taken, therefore, to always provide Latin translations of the other languages, so that users could see how the different languages related to each other. Different translations were thought to complement one another since multiple languages could reveal a more complete meaning of Scripture than any single language could on its own.

Although translating the Bible into multiple languages was just one of the feats of this project. Another major challenge faced by the printers of polyglots was ensuring that all the languages printed on a single page showed exactly the same amount of text. With the nine languages in the London polyglot, it was particularly daunting in this regard.

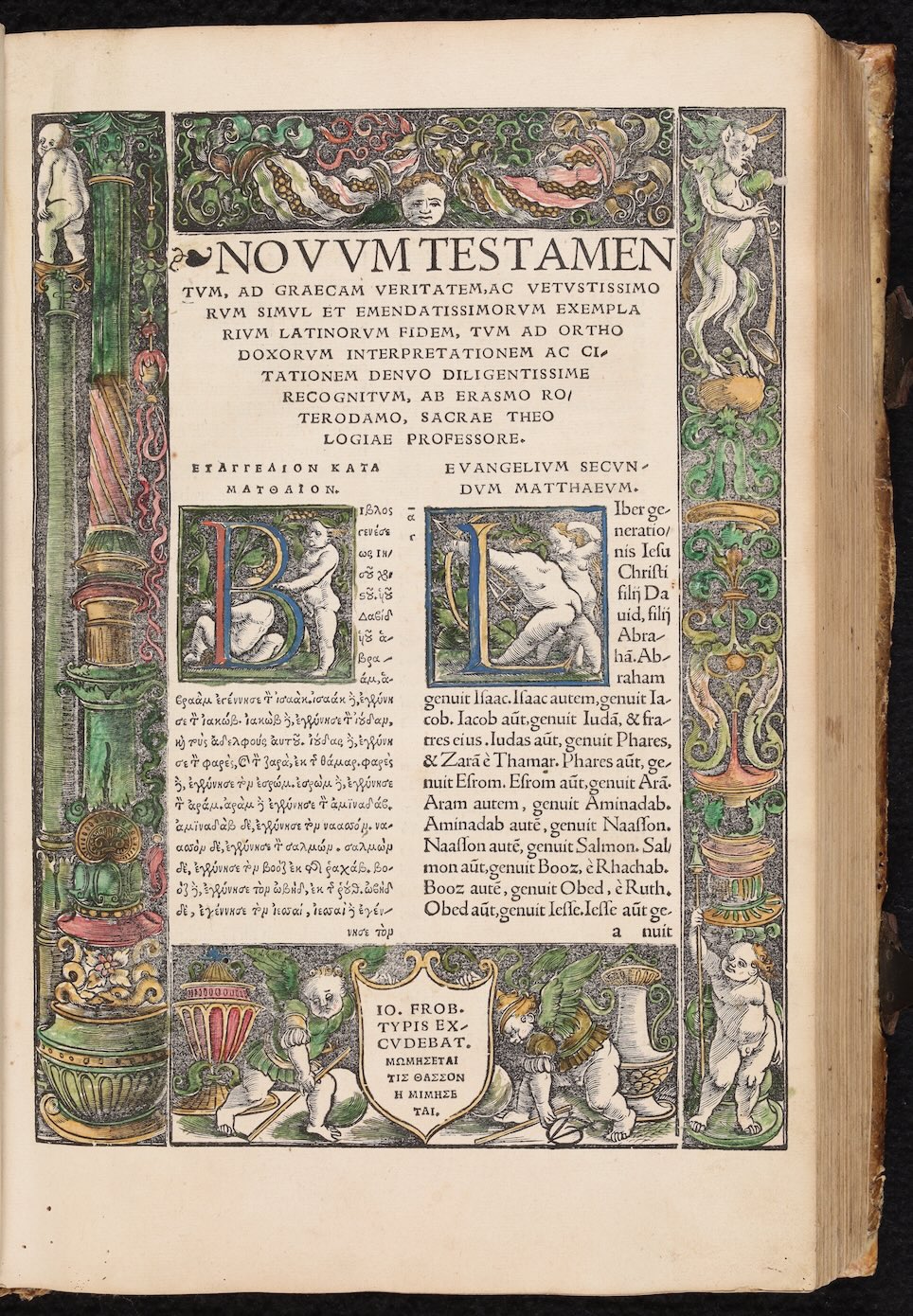

Translation from a great Renaissance humanist

Nouum Testamentum omne multo quàm antehac diligentius ab Erasmo Roterodamo recognitum: emendatum ac translatum, non slum ad Graecam ueritatem, uerum etiam ad multorum utriusque linguae codicum, 2nd edition.

Basel: Johann Froben, 1519.

Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) was part of the Renaissance movement back to classical sources of knowledge. Erasmus, a devout Catholic, believed that the Church could be spiritually reformed by a return to its roots in the Bible, as understood by the early Church fathers. Novum Testamentum Omne is a bilingual Latin—Greek New Testament with substantial annotation. The first edition was published in 1516 and is considered the first New Testament printed in Greek. The second edition, on display here, was published in 1519 and made substantial changes to translation mistakes, transcription errors, and typos with almost 400 changes made to the Greek. Importantly, included in this edition is a letter of recommendation from Pope Leo X. This gave a papal stamp of approval to the text and author.

Curator(s)

Dr. Audrey Thorstad; Taylor Samuelson (CSB+SJU class of 2025)

Credits

Special thanks for their contributions to Tim Ternes, who helped install, guided, and supported this exhibition; Dr. Matthew Heintzelman, whose knowledge of the collections and assistance locating materials was indispensable for this exhibition; Katherine Goertz, who helped locate materials from Arca Artium Art Collection; Dr. Matthew Harkins, whose expertise helped make connections between materials; Wayne Torborg and Mary Hoppe, who provided the digital photos throughout the exhibition; and John Meyerhofer, who prepared the online version. And to the Saint John’s University Archivists, Peggy Roske, Liz Knuth, and Br. Eric Pohlman O.S.B., for their generous loan of yearbooks and photos for the physical exhibition.