Preserving Pages

Preserving Pages

60 Years of Sharing the World’s Handwritten Past

Looking back on the 60 years the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML) has existed, its purpose—to preserve our global cultural heritage from deterioration and possible endangerment—has never wavered. However, even as HMML’s mission has remained the same, few could have imagined the evolution of HMML from the first progress report in 1965 to today. This exhibition offers a snapshot of HMML’s growth through its 60 years of operation, including the expansion of its partnerships, the digitization of manuscripts from microfilm, and the global reach of these manuscripts through HMML’s virtual Reading Room (vHMML). The exhibition takes you on a journey through preservation projects across Europe, Africa, and Asia, where HMML works with local libraries and archives to preserve and share manuscripts through community-based preservation. Local teams are provided with equipment, training, technical support, and payment for their work. Copies of the digital images are given to the repository that holds the manuscripts. Another copy comes to HMML. Catalogers are employed to ensure that the digital images of these manuscripts are identified, supported for long-term access, and are made freely available to the public via our website, while the original physical manuscripts remain at the repository. This exhibition displays objects from collections housed across HMML and Saint John’s University.

HMML Lands on its Feet

“In the spring of 1964 an idea crystallized at Saint John’s Abbey and University, Collegeville, Minnesota, which had been in the making for several years […] The purpose of such a project was twofold: to safeguard these valuable documents against deterioration and possible destruction; and to make them available for consultation by American scholars by collecting them in microfilm form in a convenient center in the United States.”

- Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Project, Progress Report I, January 1965

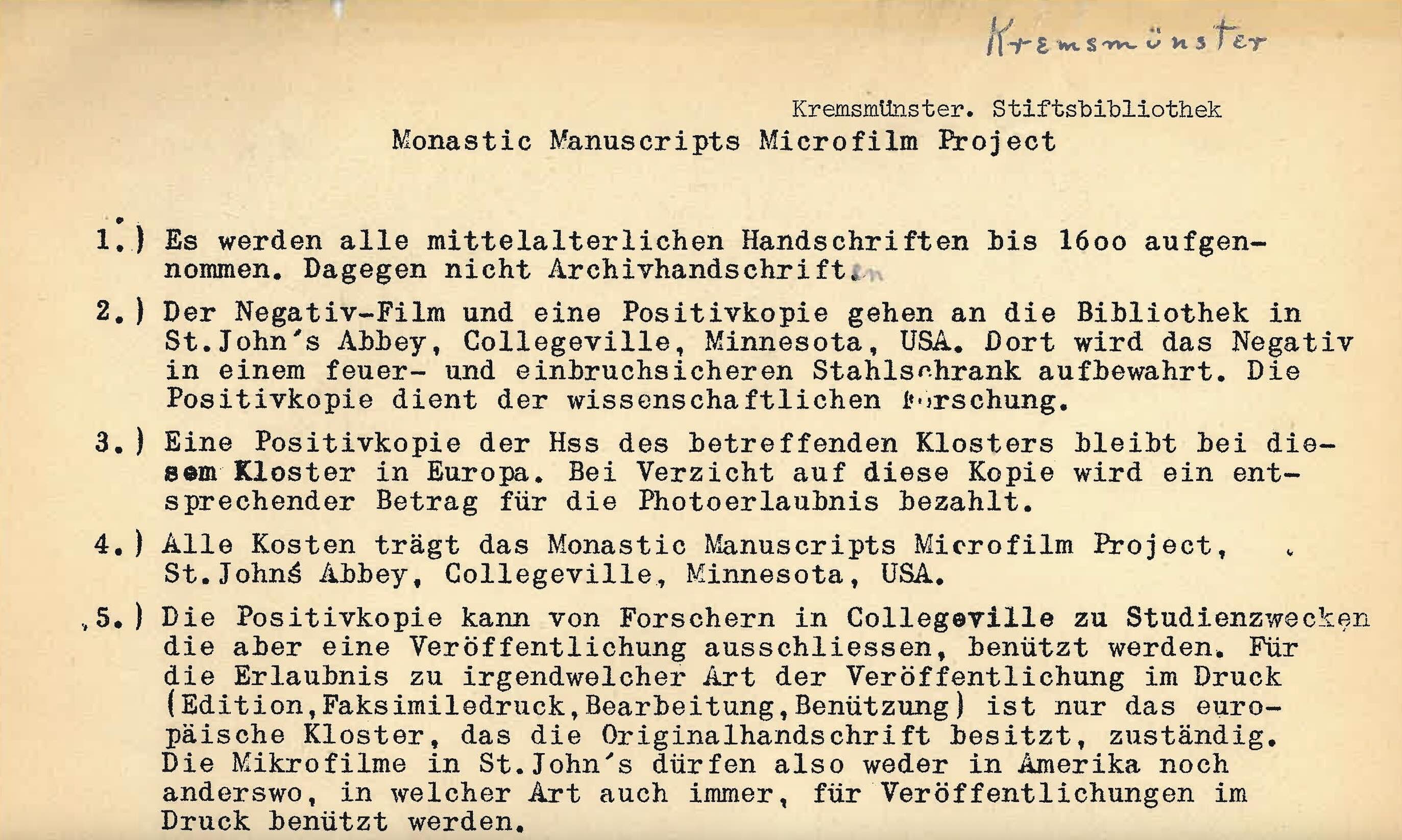

HMML’s First Contracts

Contracts with Kremsmünster Abbey.

Austria, 20th century.

“Willkommen in Kremsmünster. Sie werden in Kremsmünster anfangen (Welcome to Kremsmünster. You will begin your work here).” These words began Fr. Oliver Kapsner’s, and thus HMML’s, journey into photographing manuscripts. This is HMML’s first signed contract, which began the work that has continued for 60 years. In Austria, the team worked with material dating from the 8th to the 17th centuries. Over the 8 years HMML worked there (1965-1973), more than 30,000 manuscripts were microfilmed at 70 different places throughout Austria.

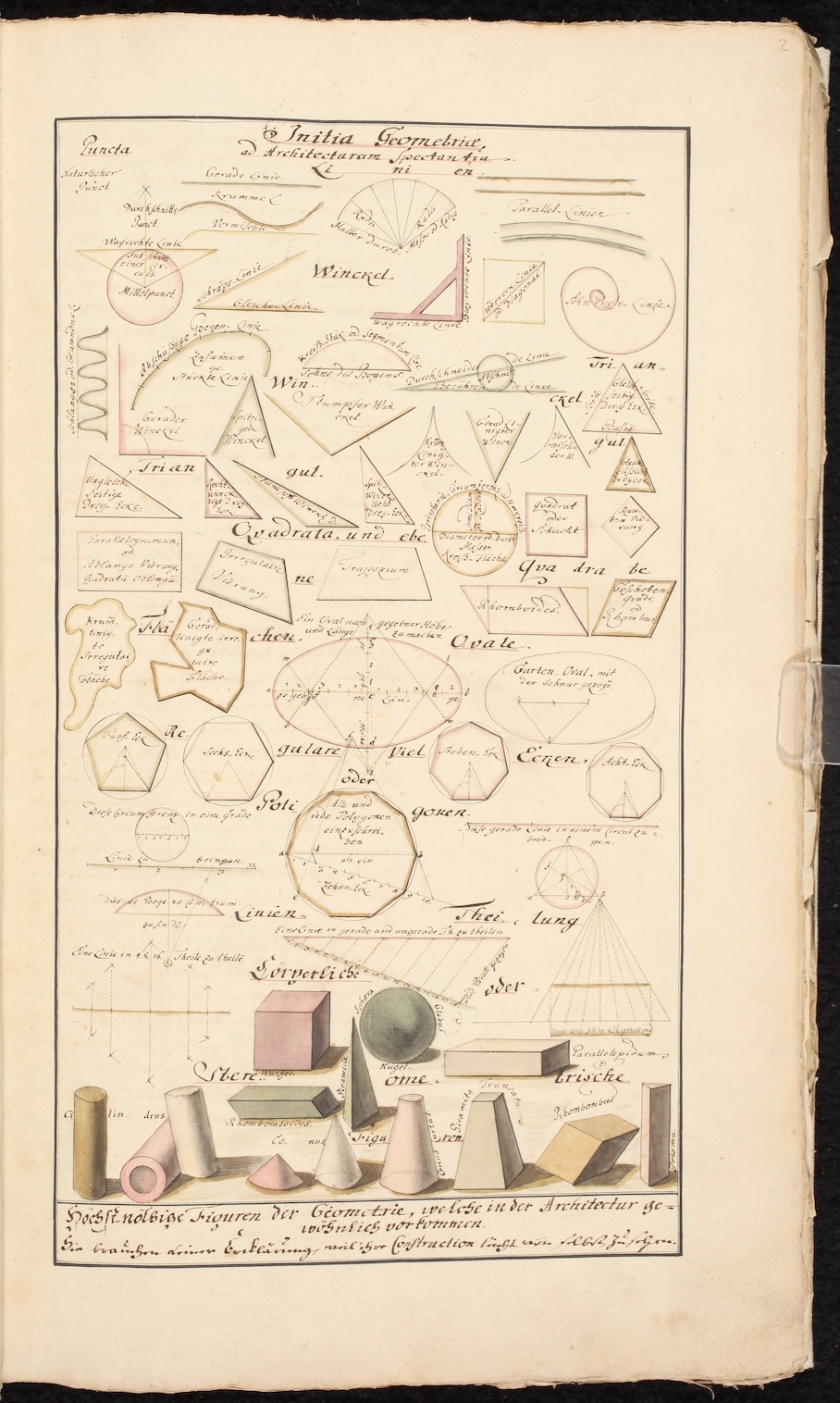

Collection of Architectural Drawings

Vortrãge der Baukunst (Lectures on Architecture).

18th century.

“We are dwarves perched on the shoulders of giants. Though we may see more and farther than they, it is not because our sight is keener or our stature greater, but because they bear us up and raise up by their own gigantic height.” – Bernard of Chartres. This manuscript is a compilation of lectures on architecture. The text is primarily written in German, but it also includes Latin and French, demonstrating the cross-cultural dissemination of information in Europe at the time.

The most popular book in the Middle Ages

Mabon Hours.

Lyon, France, 15th century.

The word ‘manuscript’ translates to ‘written by hand,’ and as such, one will find no two manuscripts the same. Copies of the same text may have different calligraphy, illuminations, and/or bindings based on local customs or the manuscript writer, which is one reason HMML works to preserve all manuscripts with partnering communities. A Book of Hours, such as this one, is a clear example of a manuscript’s originality; a collection of devotional texts, a Book of Hours contains prayers centered around the Hours of the Virgin, or the Virgin Mary.

Forming the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML)

When the Acting Patriarch of the Ethiopian Church, His Holiness Abuna Theophilos, suggested an idea to microfilm all the manuscripts in Ethiopia, no one could have predicted the size and length of the project. His Holiness’ suggestion came due to an increased worry about deterioration, theft, and a pursuit to allow scholars access to these documents. To this end, a committee appointed by His Holiness explored this idea; among the members was Dr. Julian G. Plante, then Director of the Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library (present-day HMML). What they devised was to be known as the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML), which worked to secure microfilm of all the manuscripts from Ethiopian churches and monasteries. These microfilm copies of texts were sent to be stored at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML) for use by scholars.

Starting in late 2004, HMML started the digitization of all the EMML films in its collection in order to make the images available online, not just on microfilm. This started a 20-year process that only recently finished in June 2025.

Prayer Scrolls Past and Present

Prayer Scroll.

Ethiopia.

Ethiopian prayer scrolls are made by Däbtäras—unordained clerics of the Ethiopian Church—to fight grave illnesses through purging evil spirits and demons from the body. Practiced among Jews, Christians, and Muslims, the scrolls likely originated during the Aksumite empire (1st-8th century CE). Though the use of prayer scrolls has declined in Ethiopia since the 1970s, they are not prohibited by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church because of their incorporation of Christian texts. This particular scroll was copied for ወለተ ኢየሱስ (Walatta Iyasus).

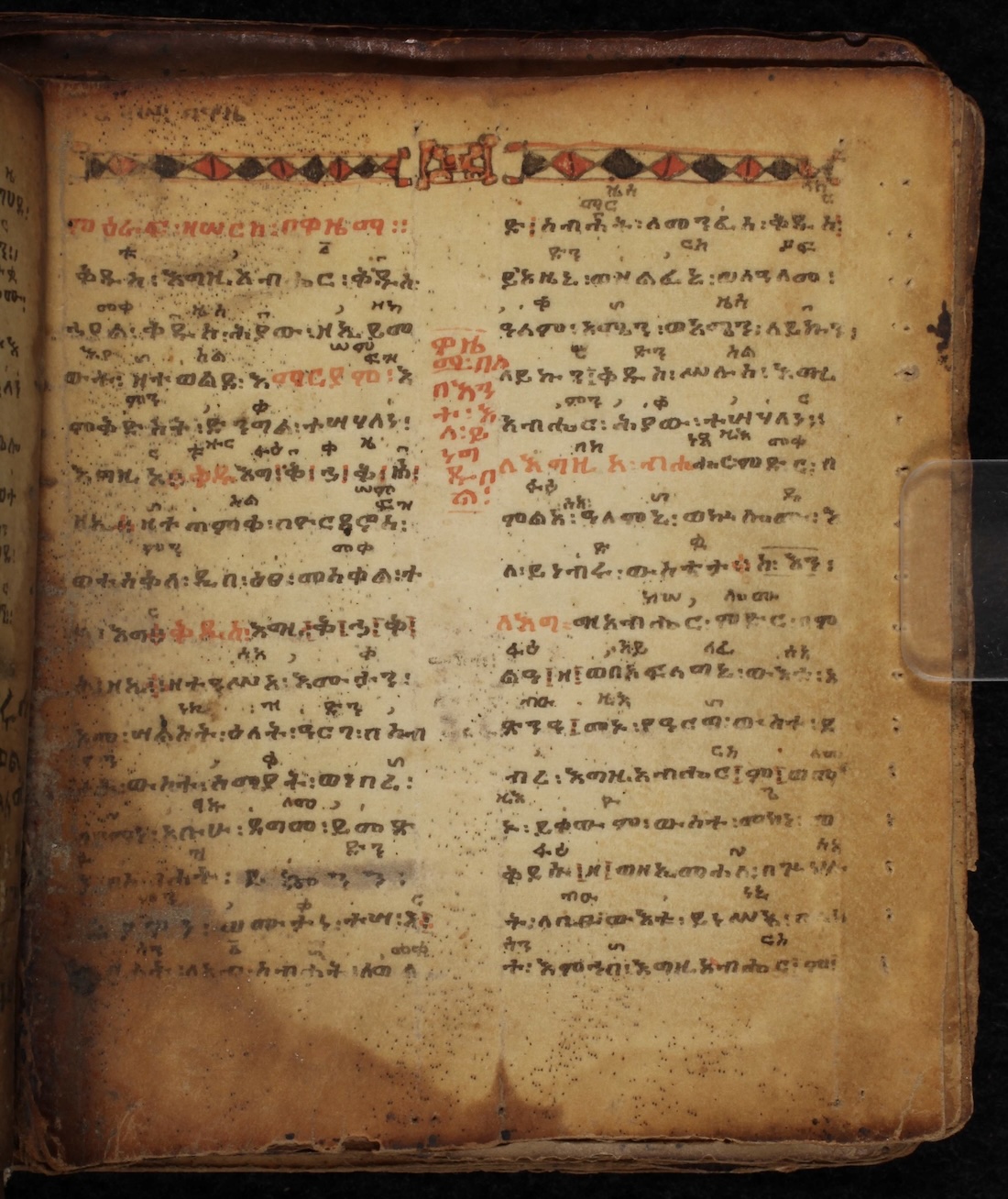

Songs for the Community

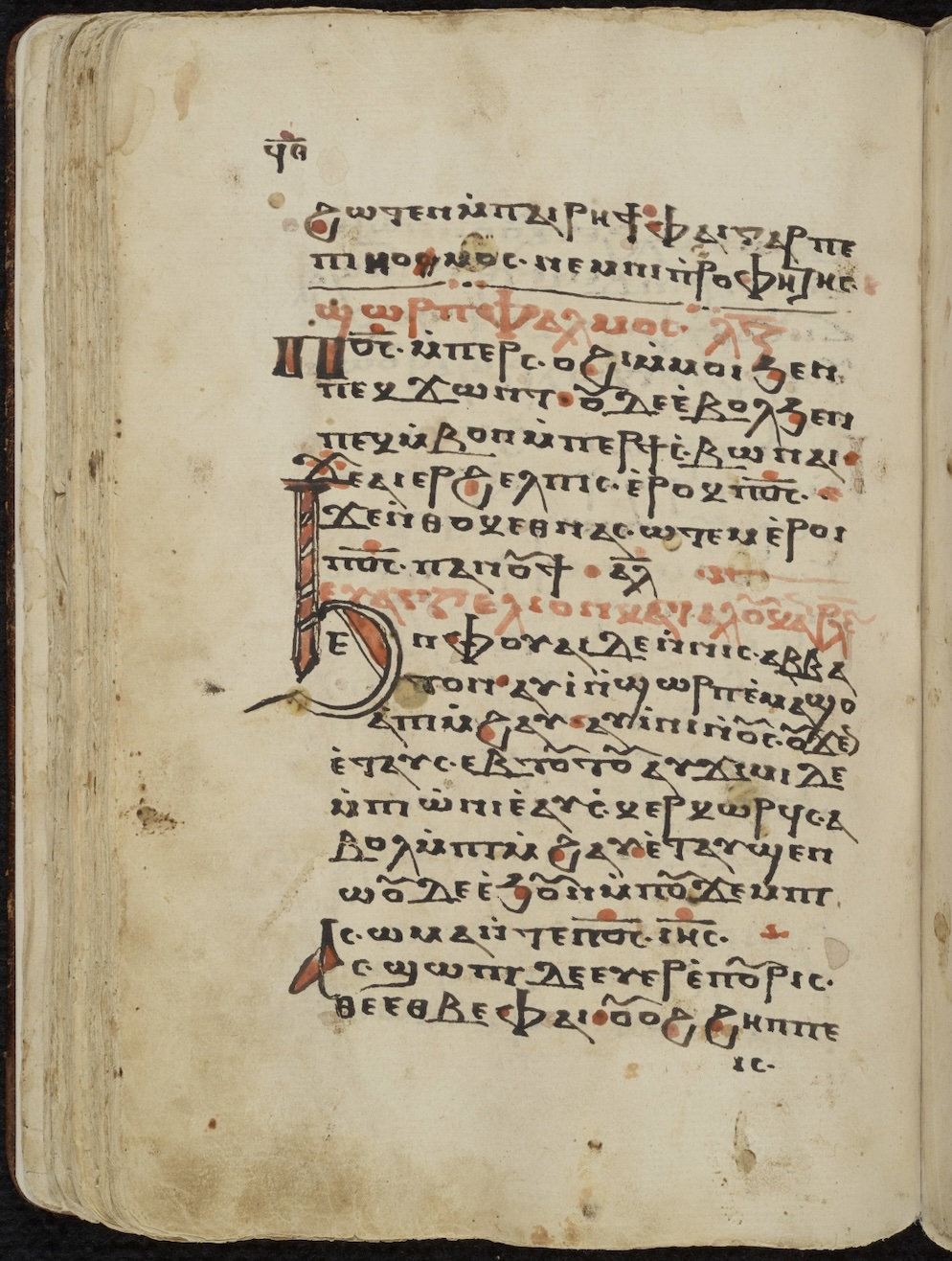

Liturgical Book.

Ethiopia, 18th century.

This collection of chants, a style of liturgical book, was to be used by a community in the church. Each chant would supply the time when the community members were to sing specific songs, and above the musical notion lay a marker—a reference for a song they learned in childhood. Most chant books, including this one, start with the praises of Mary, which is one of the most copied works in Ethiopian manuscripts. Red ink is interspersed in the text for specific signaling: dividing a section, punctuation dividers, or used for important names.

The Process of Creating a Prayer Scroll

Prayer Scroll.

Ethiopia, 18th century.

Before Ethiopian prayer scrolls are used, they must first be made specifically for the afflicted person. Alongside the writing, various images, such as eyes, are drawn on the parchment; these are non-representational talismanic designs that enhance the written prayer’s effectiveness. When the scroll is ready, the priests recite prayers, holy water is given out, and the images are displayed. This scroll was copied for ወለተ ኢየሱስ (Walatta Iyasus), erased, and replaced with ወለተ፡ ስላሴ (Walatta Selāssē) to show different ownership.

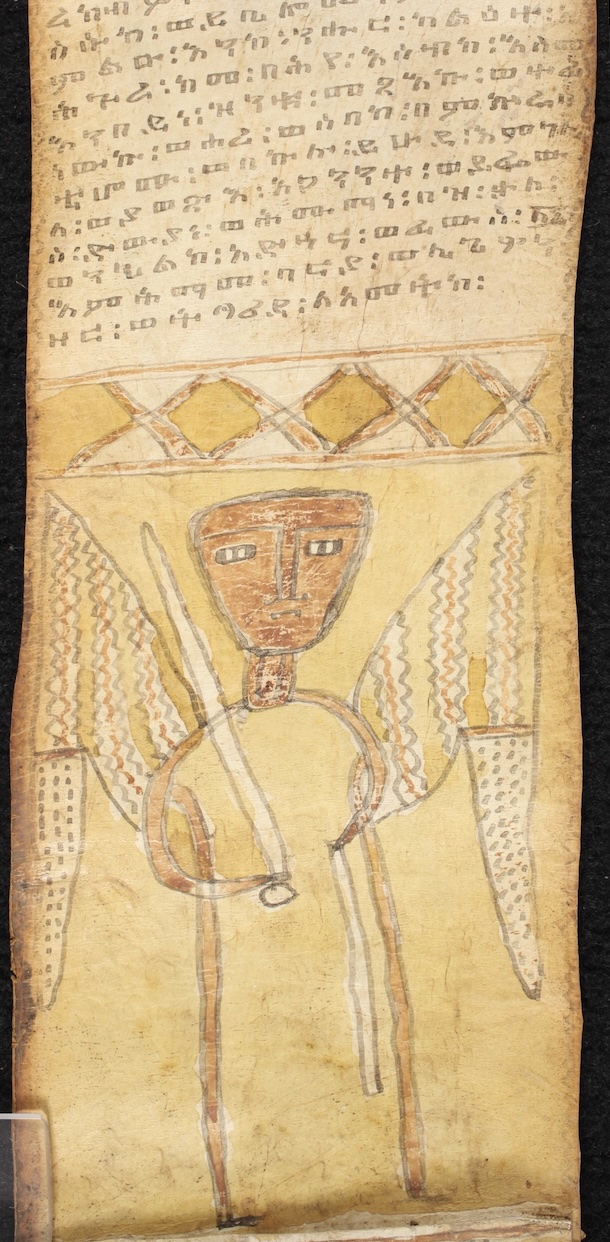

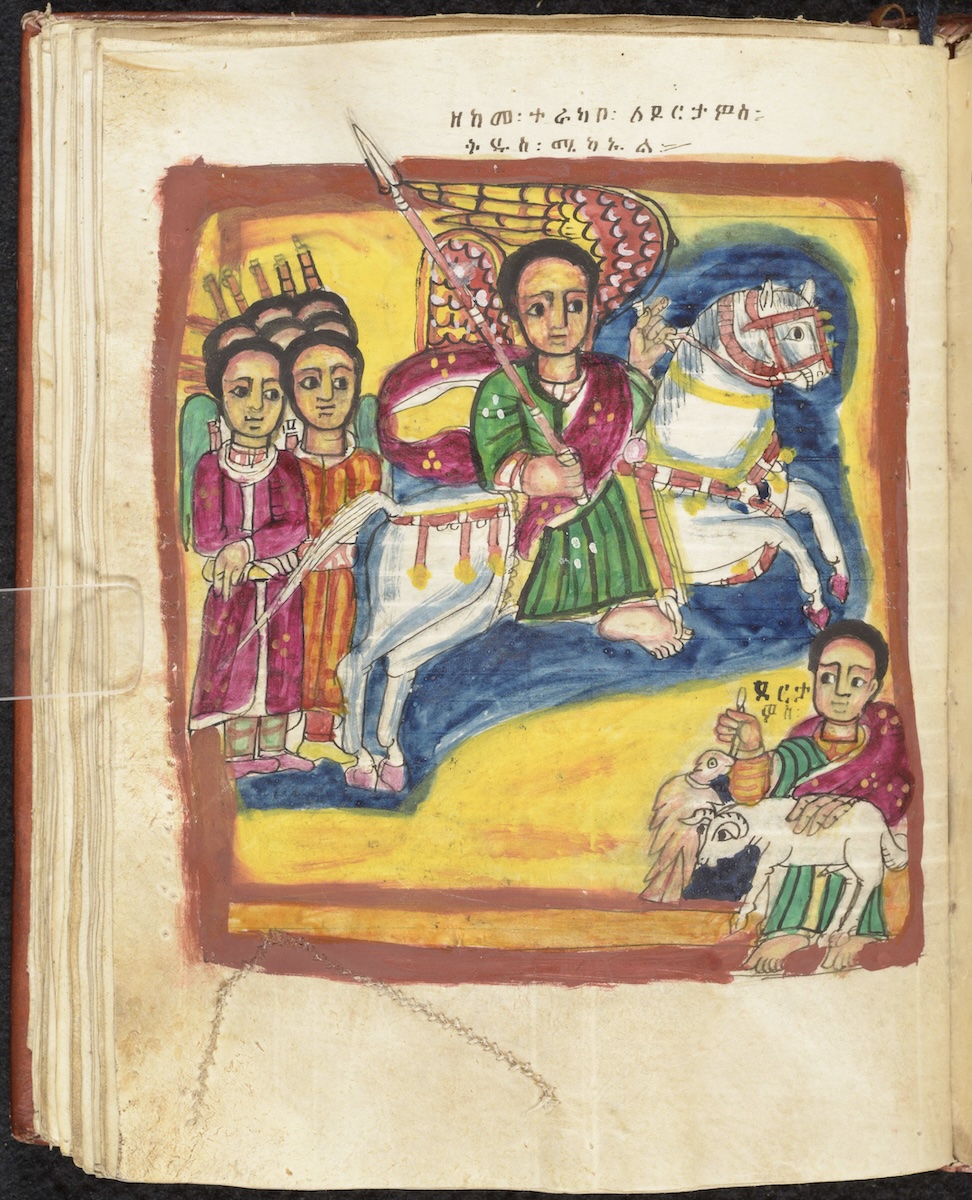

The Appearance of Angels

Homilies in Ge’ez.

Ethiopia, 20th century.

Many different angels make an appearance in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church’s text, with Michael the archangel being a prominent figure. This manuscript is arranged for the monthly feasts of the archangel Michael alongside thirteen full-page miniatures, mostly from specific moments of the Bible. Additionally, the patron of this manuscript is included in the thirteenth miniature; often, the patron is painted kneeling at the feet of a saint. These miniatures seem to have been done in concurrence with the writing of the manuscript.

Expanding Beyond Austria’s Borders

Though initial interest was placed on European manuscripts, with microfilming beginning at Kremsmünster Abbey in northern Austria, HMML now places priority on manuscripts in regions endangered by political instability, war, or other threats that go beyond Austria. The preservation of these manuscripts begins through partnership with the local libraries; HMML partners with local repositories to make digital images of the manuscripts in their collection, which is done through local teams on site, providing them with equipment, training, technical support, and payment for their work. Since there is no way of knowing what may be of significance in the future, everything is photographed in the collection to be cataloged and made freely available online.

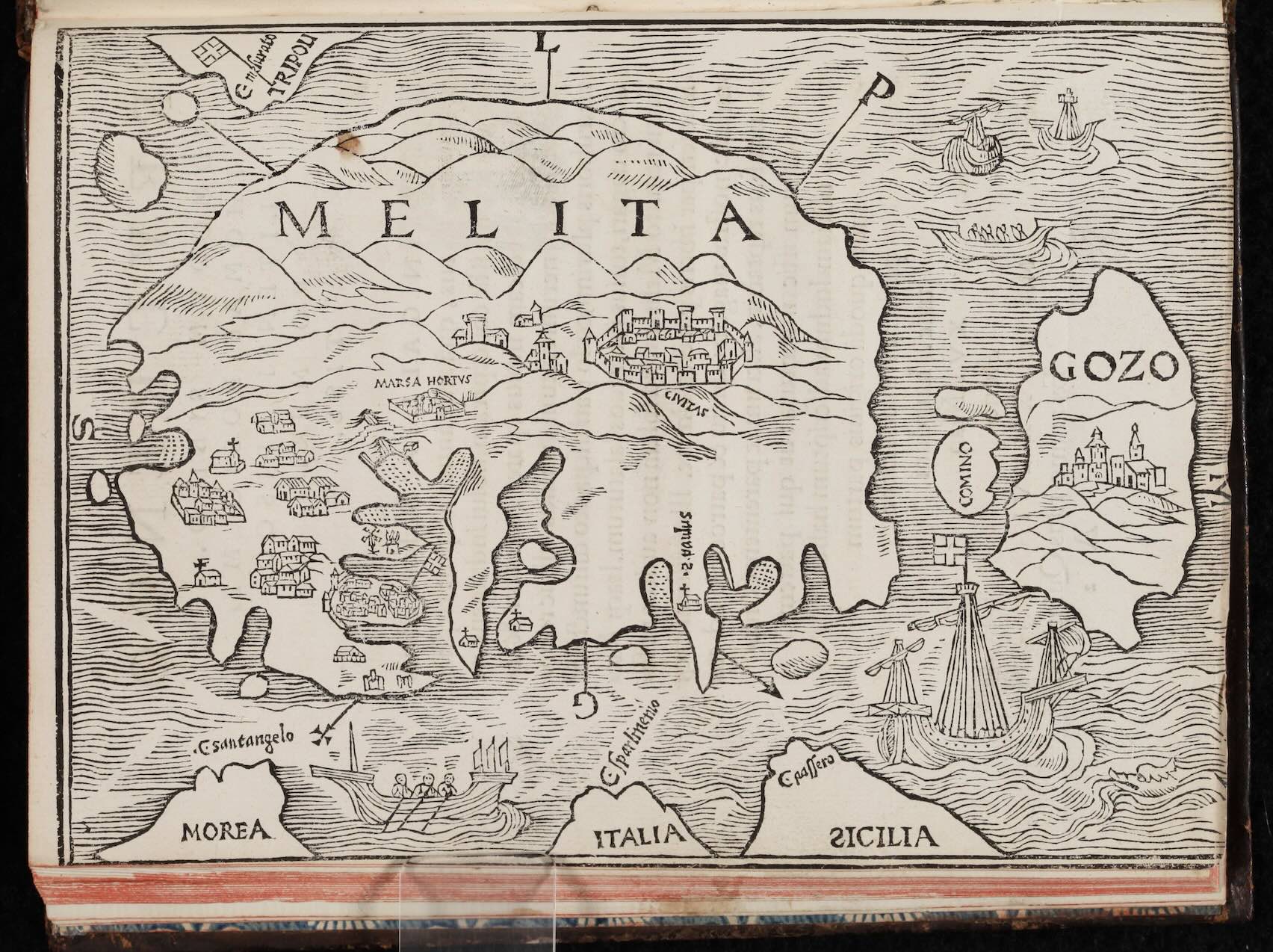

The earliest printed map of Malta

Jean Quintin, Insulae Melitae descriptio ex commentariis rerum quotidianorum.

Lyon: Sebastianus Gryphius, 1536.

Since starting work in 1973, HMML’s partnership with Malta has become the oldest continuous microfilm and digital preservation project HMML has worked on. The Malta Study Center holds the largest image collection of manuscripts, art, and archival material from Malta and Gozo. This map by Jean Quintin, a chaplain of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, was written to record his visit to the Maltese archipelago after the Order took control of the islands in 1530. His detailed discussion of the towns, landscape, and sites of Malta became the standard description of the island used by later writers when composing atlases or other geographic works.

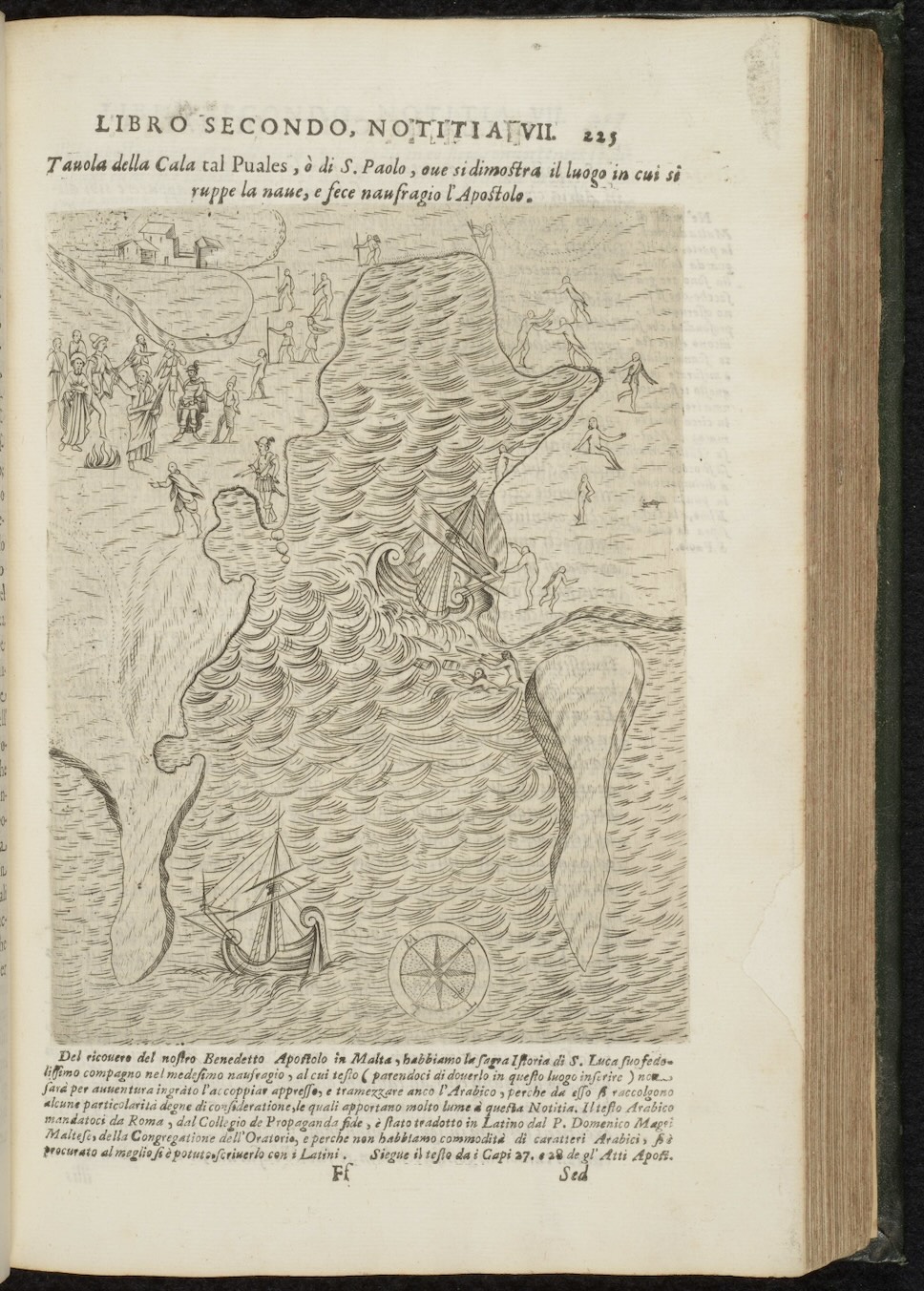

Malta mapped into Christian history

Giovanni Francesco Abela, Descrittione di Malta Isola nel Mare Siciliano con le sve Antichita, ed Altre Notitie Libro Quattro. Malta: Paolo Bonacota, 1647.

Medieval and early modern scholars debated the site of Saint Paul's Shipwreck due to the ambiguous language of Acts of the Apostles (Acts 27:27 and Acts 28:1) coupled with the fact that there were multiple islands in the Mediterranean. Giovanni Francesco Abela's map of Saint Paul’s Bay in Malta illustrated Malta's claim to be the site of Saint Paul’s Shipwreck, depicting the shipwreck itself and the miracle of the serpents. The Malta Study Center, founded in 1973, preserves items, like this map, that record a millennium of history witnessed through the island's crossroads, as well as collections dedicated to Malta and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.

Malta as a militarized bastion and sovereign state

Pianta Geografica delle Isole di Malta, e Gozo della Sagra Religione Gerosolimitana di S. Giovanni delineata, ed incisa in quest'anno 1761, sotto gli auspicj dell'Emminentissimo Signore Gran Maestro F. D. Emmanuele Pinto. Palermo: Antonio Bova, 1761.

Antonio Bova's map, highlighting the defensive fortifications and military might of Malta, supported Grand Master Emanuel Pinto da Fonseca's claims to princely and sovereign status of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem over the island. The inclusion of the Order's fleet and the coat of arms of the Grand Master and Order surrounded by war trophies highlights the prowess of the military religious order that governed the island since 1530. The Malta Study Center continues to work tirelessly to preserve and share the rich history of the Order of St. John.

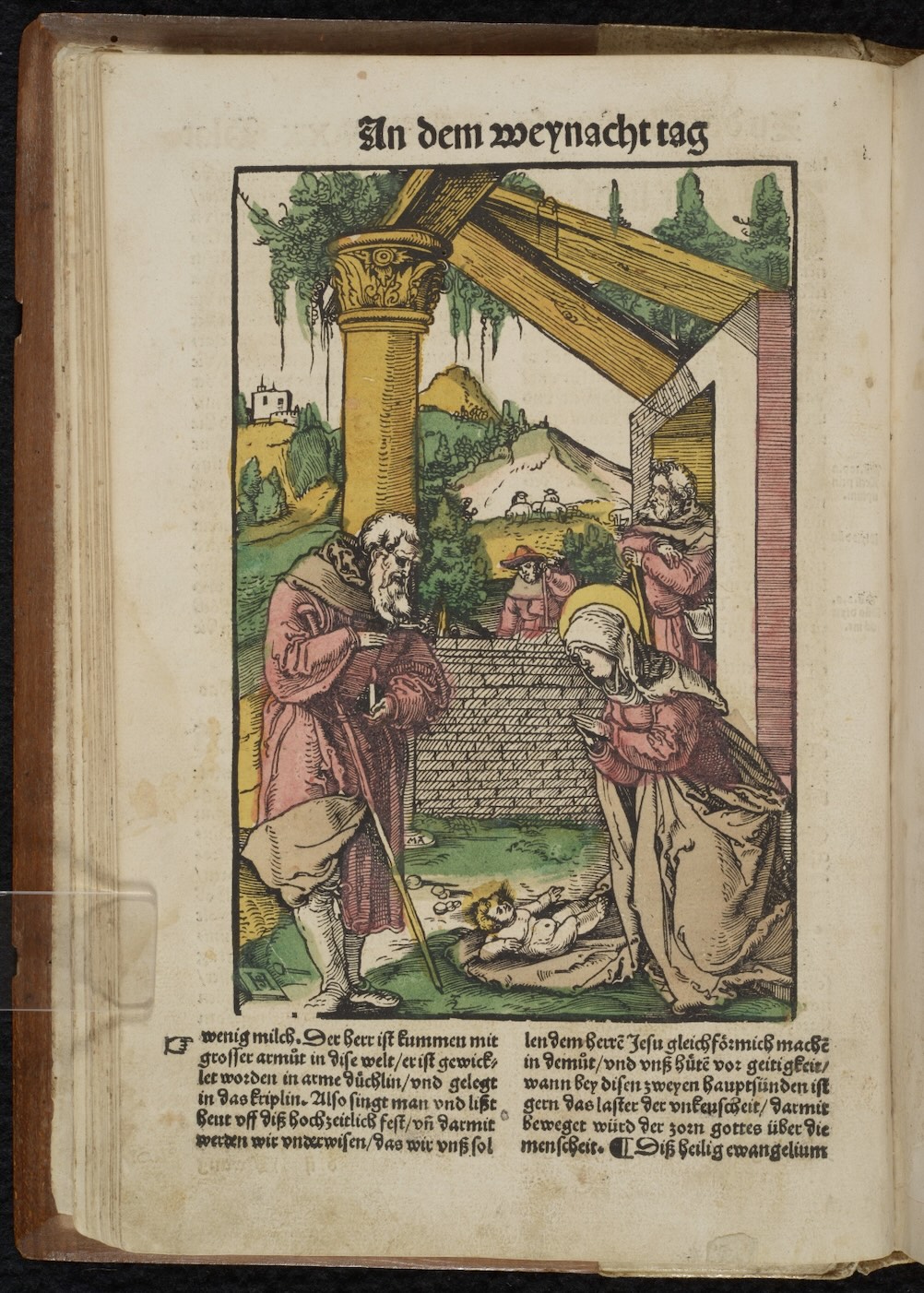

Tried and True Printmaking

Das new Plenarium oder Ewangely-Buch.

Switzerland, 16th century.

Woodcuts are the oldest form of printmaking, in which knives and other tools carve into the surface of a wood block and create a raised area. Two areas on the woodcut are left: the raised area, which will be inked and printed, and the areas carved that will not retain ink. If the book is also being printed, the wood block can be printed alongside the typeface in the same press, making the process easier than separating the printings. These woodcuts have also been hand-colored, which creates a unique viewing experience as opposed to the typical black and white woodcuts.

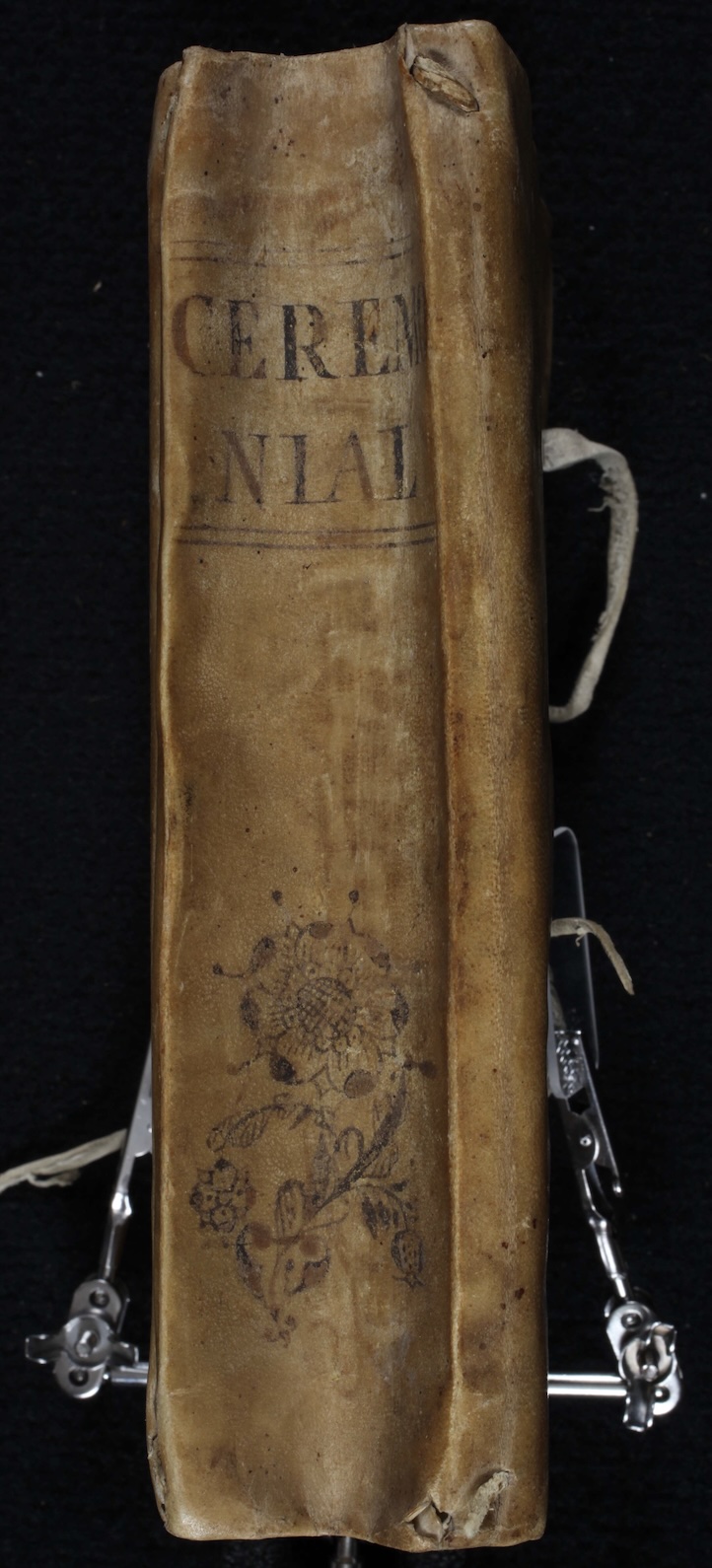

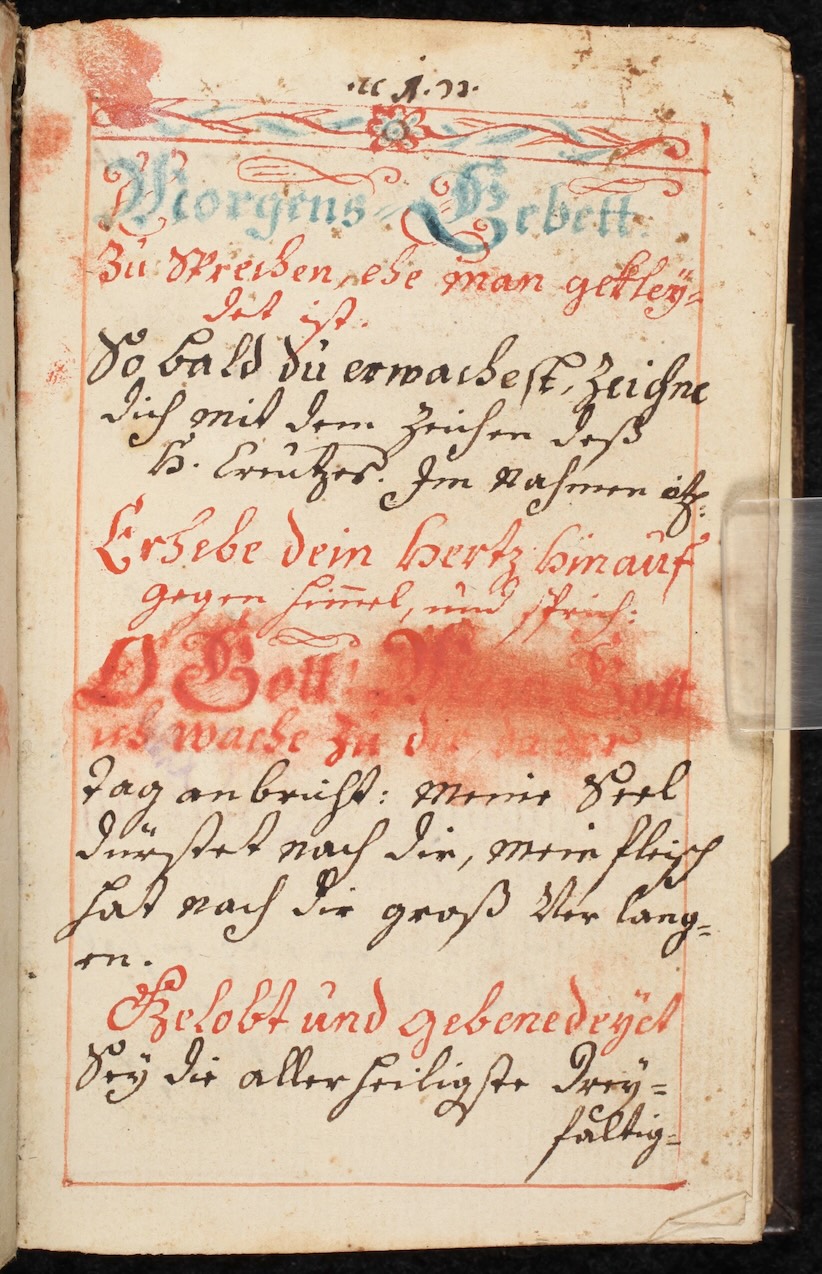

Bookbinding for Every Occasion

Prayer Book and other devotional texts.

Spain, 18th century.

Several bookbinding methods exist for manuscripts and printed books, depending on personal preference, durability, and other factors. This manuscript demonstrates what is known as limp binding, where the cover is made from a single piece of vellum folded around the text block (or leaves of a book). Much of limp binding was used for commonplace books—a collection of texts by the owner of the book, arranged under a general topic or theme. This manuscript contains a variety of texts and is written in different hands over several years.

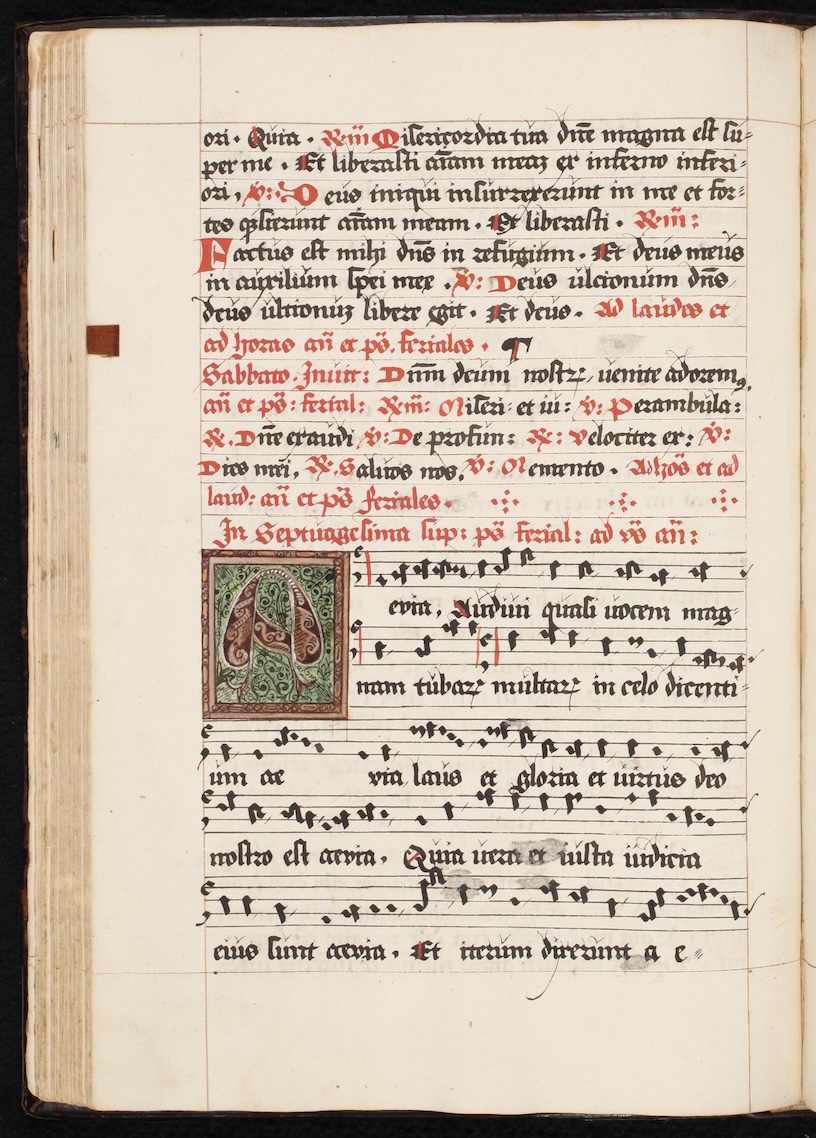

A Community Song Book

Liber responsorialis et antiphonale pro vigiliis nocturnis et diurnis horis.

Germany, 1587.

Between 1978 to 1999, HMML worked with 50 repositories and universities in Germany to microfilm some 14,000 manuscripts. The content in these volumes is important, as is the materiality of the book itself. For example, sometimes the outside of a book can tell us how it was stored. In the medieval period, clasps would hold the book shut, helping preserve it from moisture and providing pressure to keep the pages flat. A choir book like this might have been used quite often by large groups of singers who would follow along together using a single book.

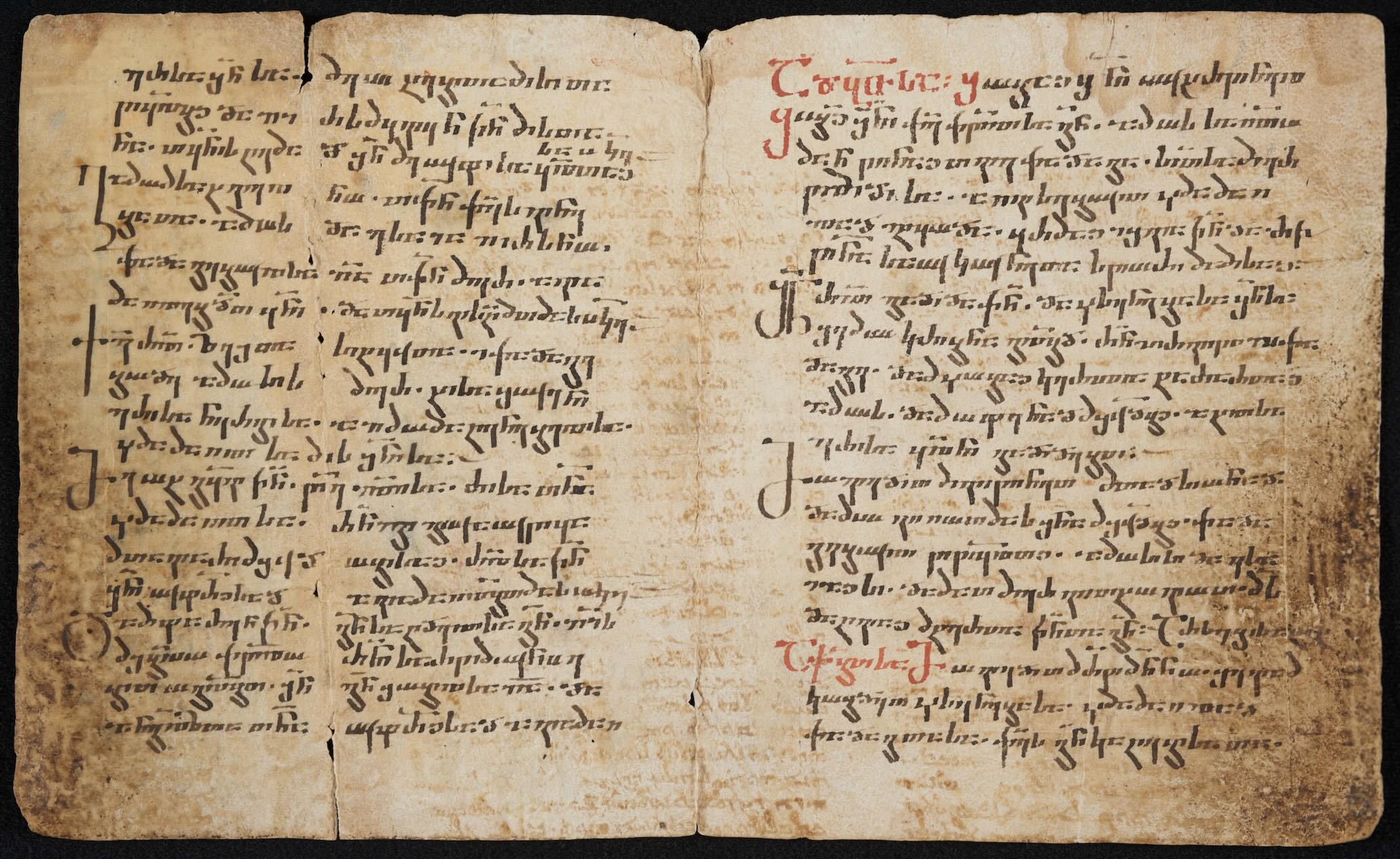

The Palimpsest’s Secret

Manuscript Fragment.

Egypt(?), 10th century.

During the Middle Ages, parchment—an expensive sheet made from animal skin—was in high demand for its usage in creating new text. The practice of reusing a piece of parchment by mechanically scraping or chemically scrubbing the parchment was a common solution to the demand. After scraping the parchment, it was clean enough to write a new text on it; this is known as a palimpsest. The palimpsest’s upper text is from a 10th-century Georgian liturgical manuscript. The two lower texts are suggested to be as early as 6th to 8th century Syriac and were found through x-ray fluorescence (XRF). To find out more about imaging HMML’s palimpsest, read our story here.

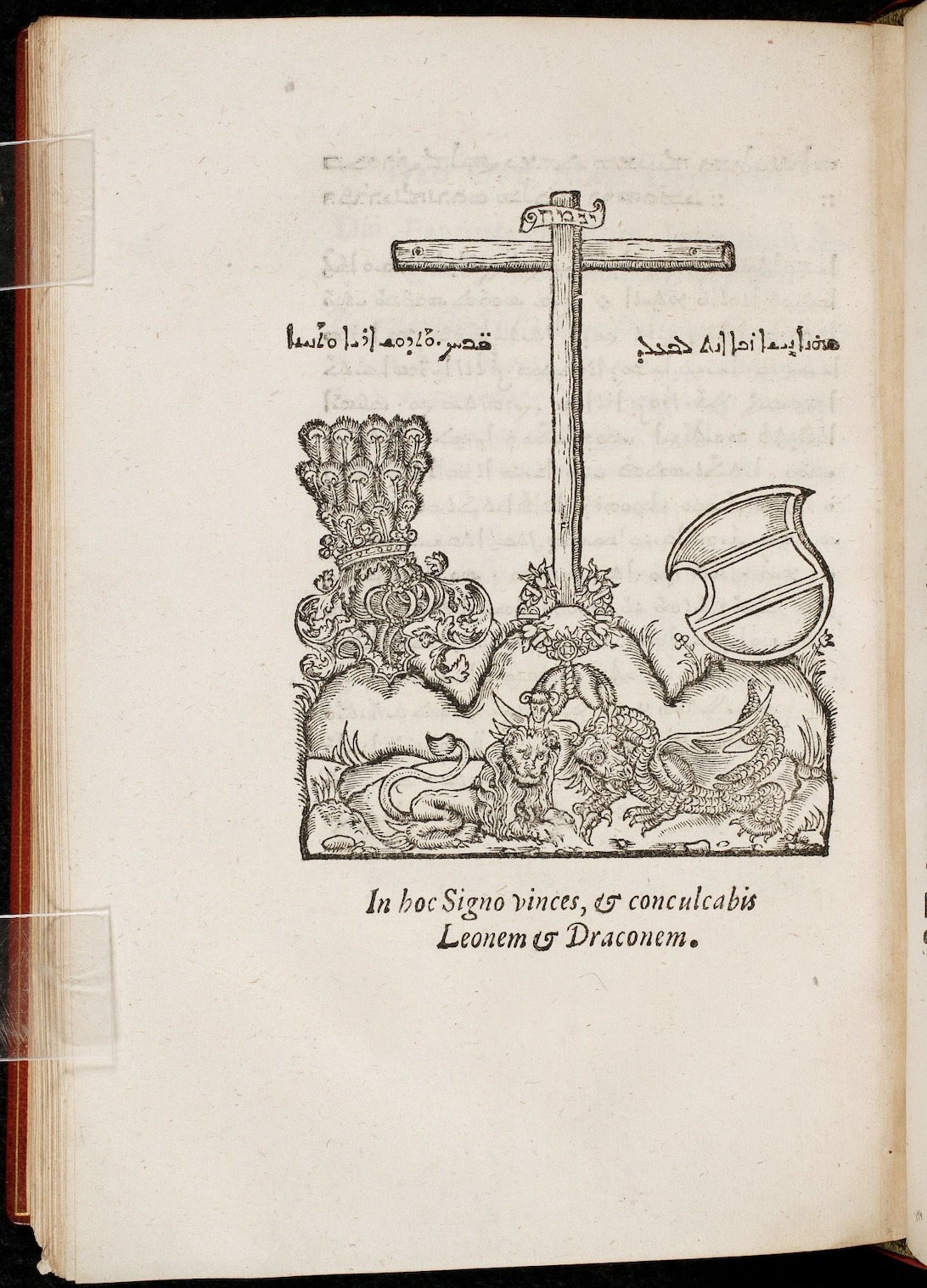

First Book Printed in Syriac in Austria

Liber sacrosancti evangelii de Iesv Christo Domino & Deo nostro.

Austria, 1555.

The Syriac language emerged during the 1st century CE and became one of the main literary languages for Christian communities in the region of Ancient Syria. This print, while typed in Syriac, was made in Vienna during the 16th century. Austria's location in Central Europe and role as the capital of the Habsburg Empire created a space of cross-cultural exchange. The empire officially recognized over a dozen languages, with several more non-official languages used throughout its territories.

Seeking Protection

Prayer Scroll.

18th century (?)

Individuals in the Armenian Church, from the 15th to the 19th centuries, often carried prayer scrolls, called Hmayil. These can be very long and are either handwritten or printed, usually with accompanying imagery. Hmayil are formulaic, containing 31 prayers in a specific order. These scrolls were made to help ward off the Devil or Evil Eye and tended to be passed down through the generations.

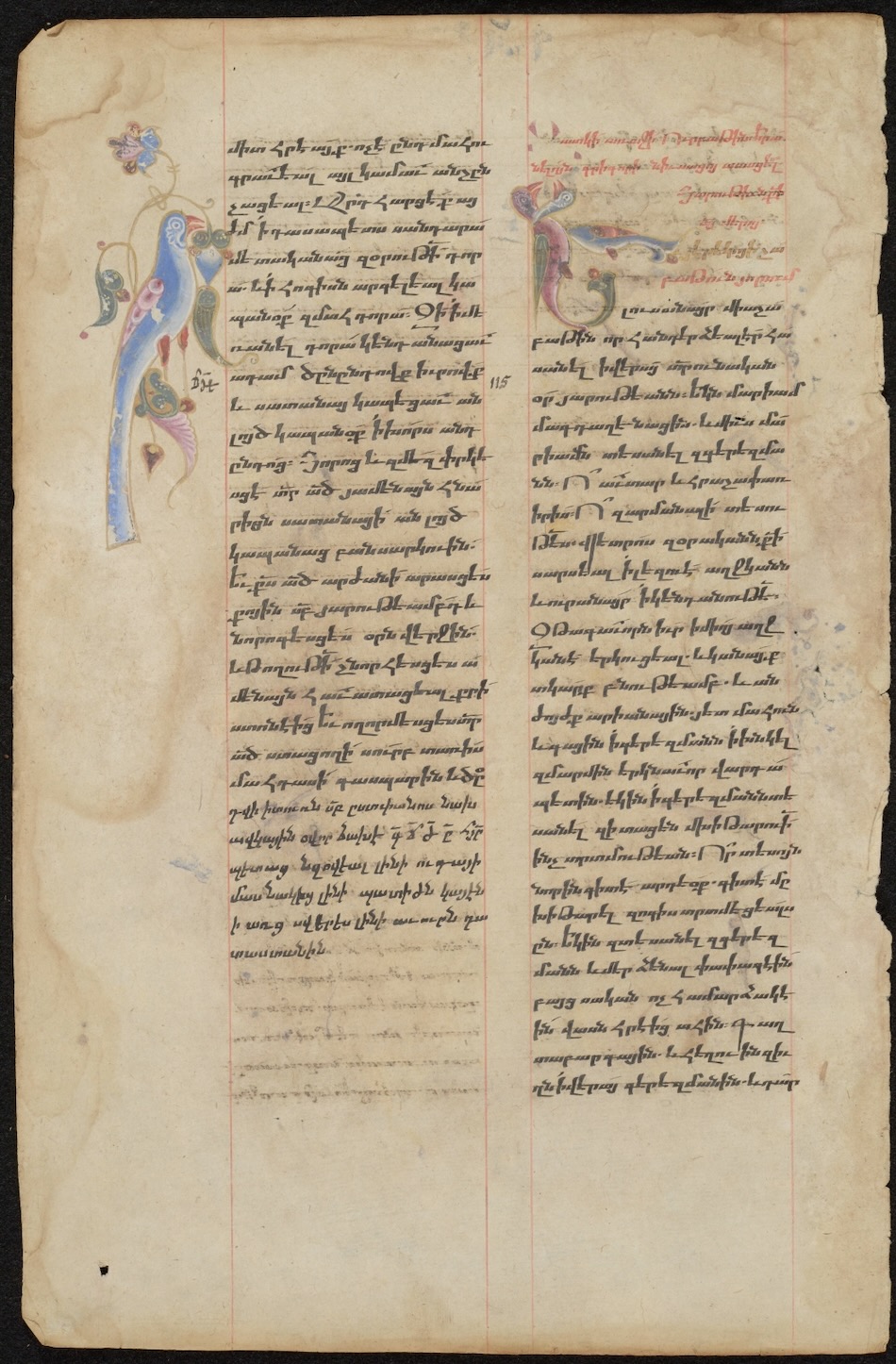

Zoomorphic Illustrations

Homiliaries in Armenian.

Armenia, 16th/17th century (?)

Animals have a long tradition in Christian texts, including Armenian manuscripts. According to Christian theology, God created animals on the fifth day, before human beings were created. As such, animals that appear in Armenian manuscripts can symbolize the creation story and the Garden of Eden. Additionally, animals symbolize biblical themes, such as the peacocks seen here, indicating resurrection and immortality; the animals often portray characteristics shaped by Armenian Christian culture and tradition. Many of these animals decorate the capital letter of a sentence or the corners of the page, which is called zoomorphic script.

HMML in the 21st century

After four decades of storing manuscript images on microfilm, HMML had amassed more than 90,000 reels of microfilm in the vault. In the next decades, HMML moved from microfilm to CDs and accumulated more than 8,500 discs. Following this, HMML switched to hard drives, which is the form of image storage still used today. During this time, HMML also assumed responsibility for Saint John's University Rare Book collection and Arca Artium art collection, expanding its physical holdings, for use in research and teaching.

Imagining the Apocalypse

Albrecht Dürer, St. John before God and the Elders.

Germany, c. 1498.

In 2005, HMML assumed responsibility for Arca Artium, or “Ark of the Arts,” donated from the personal collection of Frank Kacmarcik oblSB (1920-2004). Br. Frank, a former Saint John’s University faculty member and claustral oblate of Saint John’s Abbey in 1989, donated his collection to the University in 1995. Numbering more than 6,000 fine art holdings, his collection includes prints, book arts, graphic design, pottery, and more. One example of this collection is a woodcut print done by Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), a German printmaker, painter, and writer during the Northern Renaissance. Dürer is known as one of the finest printmakers of the European Renaissance.

Censorship in 19th-century Japan

Utagawa Kunisada, Actor Ichikawa Danjûrô VIII as Musashibo Benkei.

Japan, 1852.

For nearly a century in Edo, Japan, woodblock prints were examined by official censors and marked with the censors’ seals. Three subjects were officially banned: pornography, Christianity, and the Tokugawa family. Starting in 1842, individual censors marked approved prints with their own seals, identifiable to the individual by incorporating characters from the censor’s name. You can see censor seals on the bottom left of this item. This print depicts the renowned Kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjûrô VIII portraying the iconic character Musashibo Benkei. Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII was a tachiyaku (male role) actor known for his aragoto (rough style) performances and his exceptional popularity in young lover roles.

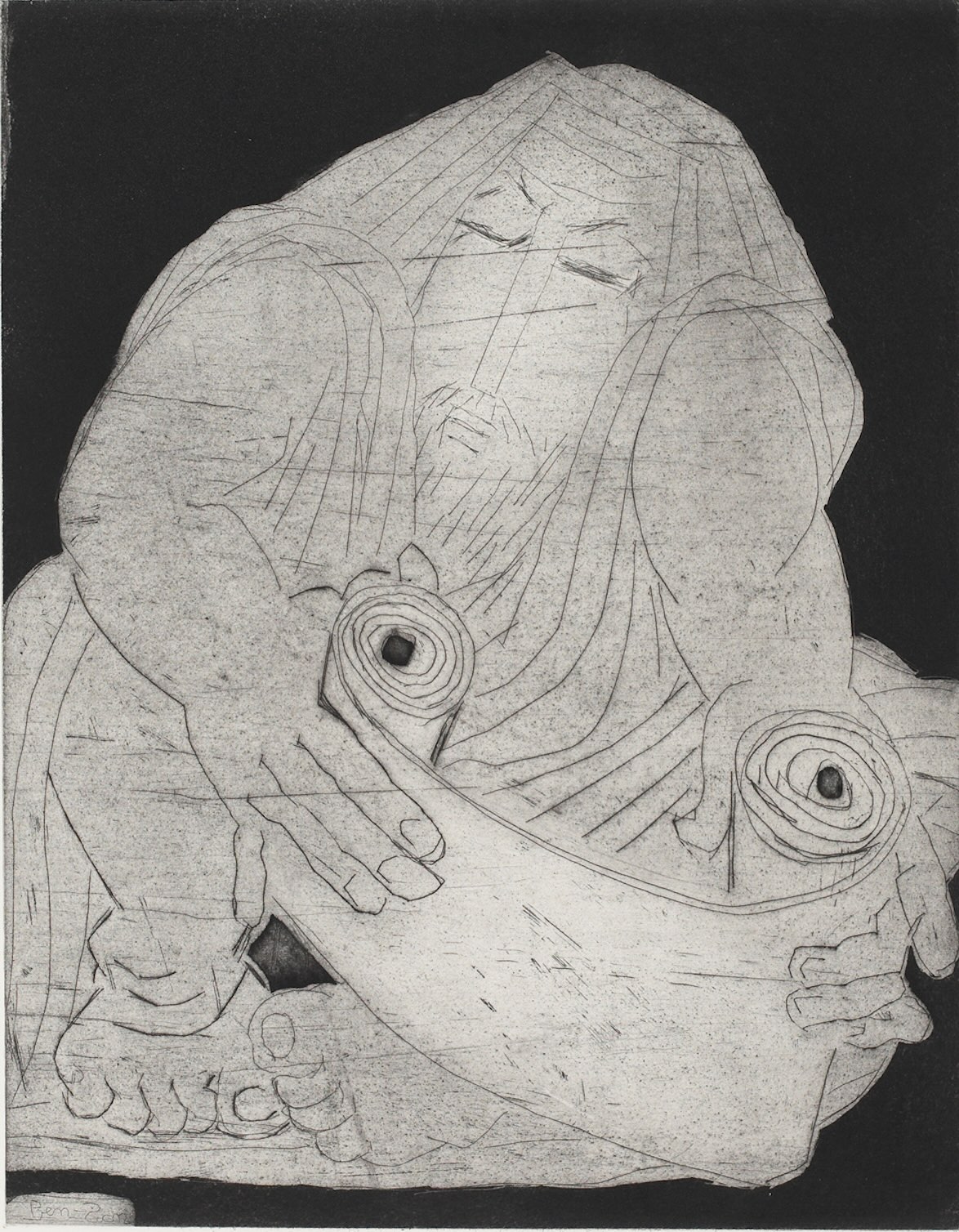

Prophets Portfolio

Ben-Zion, Jeremiah (Oh that I had in the Wilderness a lodging place of wayfaring men).

New York City, 1952.

Ben-Zion (1897-1987) was a founding member of The Ten, a group of modernist artists. He rejected the dominant movement of 1950s Abstract Expressionism, which he saw as creating impenetrable and esoteric artwork. Believing that art should be comprehensible, much of Ben-Zion’s work is straightforward, depicting figures meaningful to him. Out of this idea comes his portfolio, Prophets, referring to biblical prophets in the Hebrew Bible. You will notice in this piece that this etching from this series depicts Jeremiah unrolling a scroll. Jeremiah, who, in Jewish tradition, wrote the Book of Jeremiah, the Book of Kings, and the Book of Lamentations, is often depicted holding a scroll.

Communicating in Multiple Languages

Arabic-Turkish Dictionary.

Turkey(?), 1685.

From 2005 to 2014, HMML worked with the Armenian Patriarchate in Istanbul to digitize manuscripts still in church hands, and in 2009, they started digitizing Syriac manuscripts in the Tur ‘Abdin, or the “mountain of the servants [of God]”. During the time this manuscript was made, Turkey was part of the Ottoman (or Turkish) Empire; their official language was Ottoman Turkish, but included other languages such as Arabic.

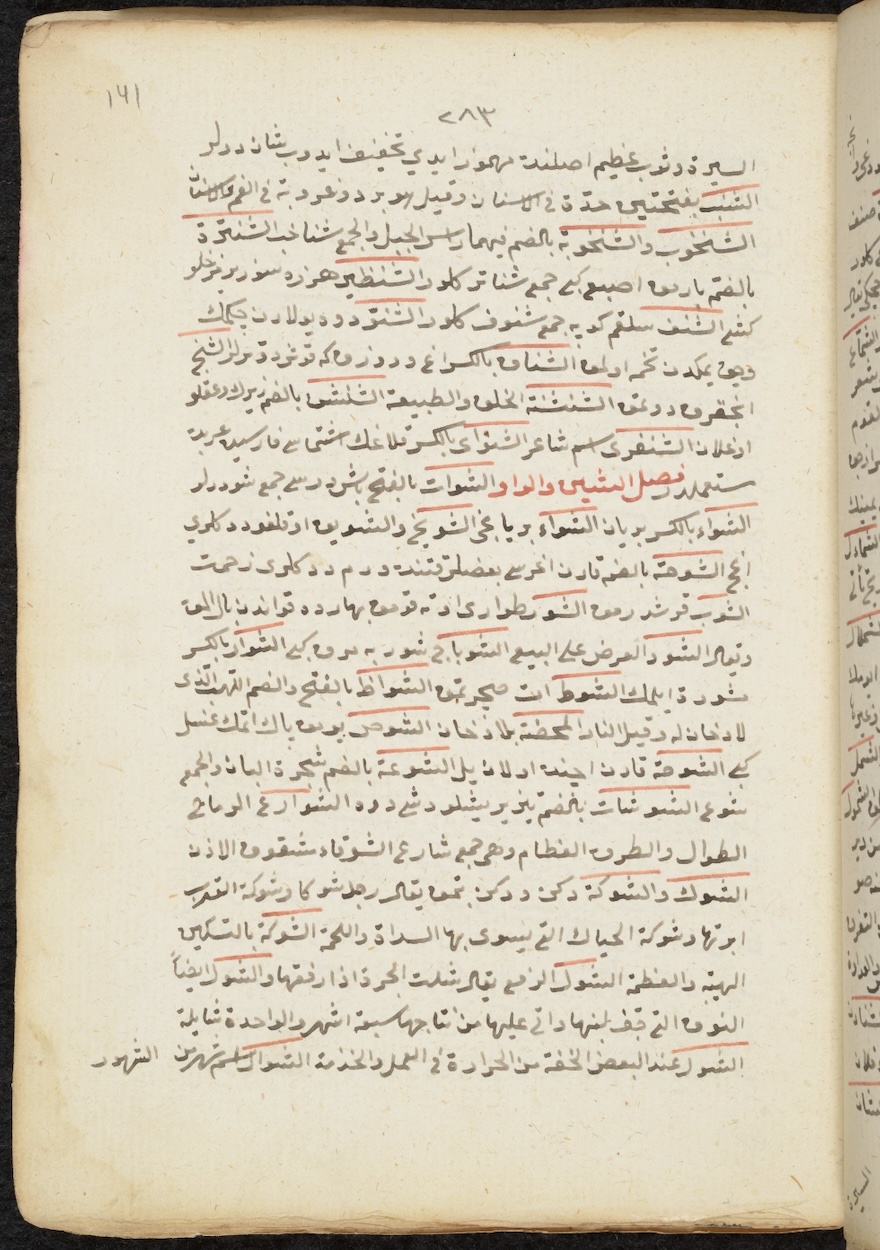

Prayers for the Prophet

Jazūlī, Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān, Dalāʼil al-khayrāt.

Mali, 21st century.

This manuscript from Djenné is just a snapshot of the work HMML did in Mali from 2013 to 2024. As HMML’s largest project to date, this work focused on West African Islamic traditions found in Timbuktu and Djenné manuscripts. Partnering with Sauvegarde et Valorisation des Manuscrits pour la Défense de la Culture Islamique (SAVAMA-DCI), HMML worked to digitize hundreds of thousands of manuscripts evacuated from Timbuktu to Bamako before the armed occupation of Timbuktu in 2012. Digitization of these manuscripts is now complete, with an estimated 4.35 million image files representing 308,000 manuscripts.

Writing Dead Languages

Bible Lectionary.

Egypt, 1856.

Some manuscripts, such as this Coptic piece, are written in what is known as a dead language—a language that may be spoken but no longer has living native speakers. Although Coptic is termed a dead language, it has both a rich history and present use. Coptic is a late form of the ancient Egyptian language of the Pharaohs, although instead of using Egyptian hieroglyphs, Coptic is written with an alphabet derived mostly from Greek. Since the Middle Ages, Arabic has been the main language used by Copts (a Christian ethnoreligious group in Northeast Africa), but the Coptic language is the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

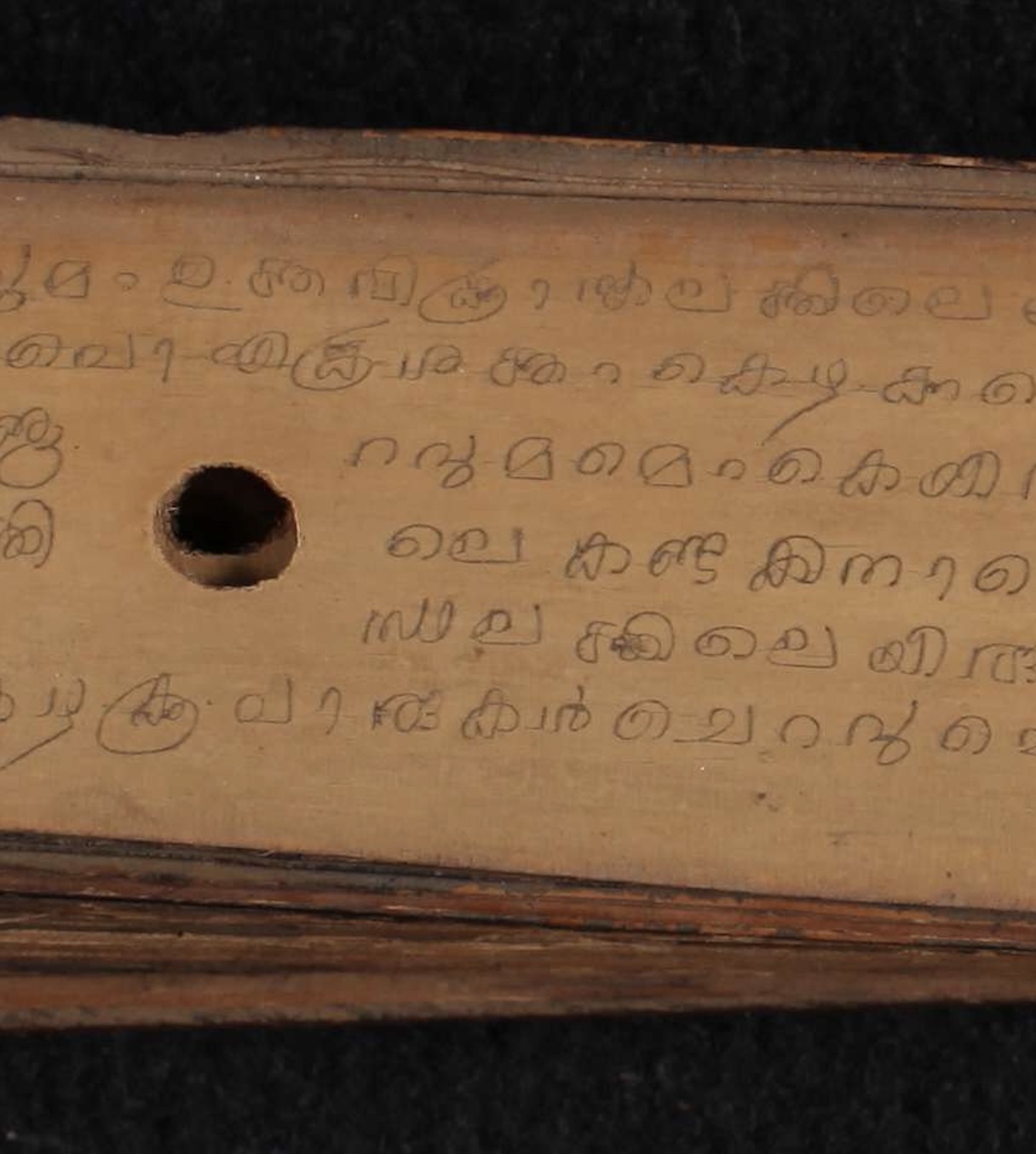

Unique manuscript material

Palm Leaf Book.

India, 19th century.

HMML’s work in India, starting in 2008, has focused on three different projects. Most recently, HMML partnered with the Digital Preservation of Kerala Archives (DiPiKA) in 2023, digitizing and cataloguing largely Hindu manuscripts written in Sanskrit, Malayalam, and Manipravalam languages. HMML is also a partner with the Digital Repository of Endangered and Affected Manuscripts in Southeast Asia (DREAMSEA Project). DREAMSEA works to preserve manuscripts written on palm-leaf – such as this – and bark paper in a variety of languages and scripts.

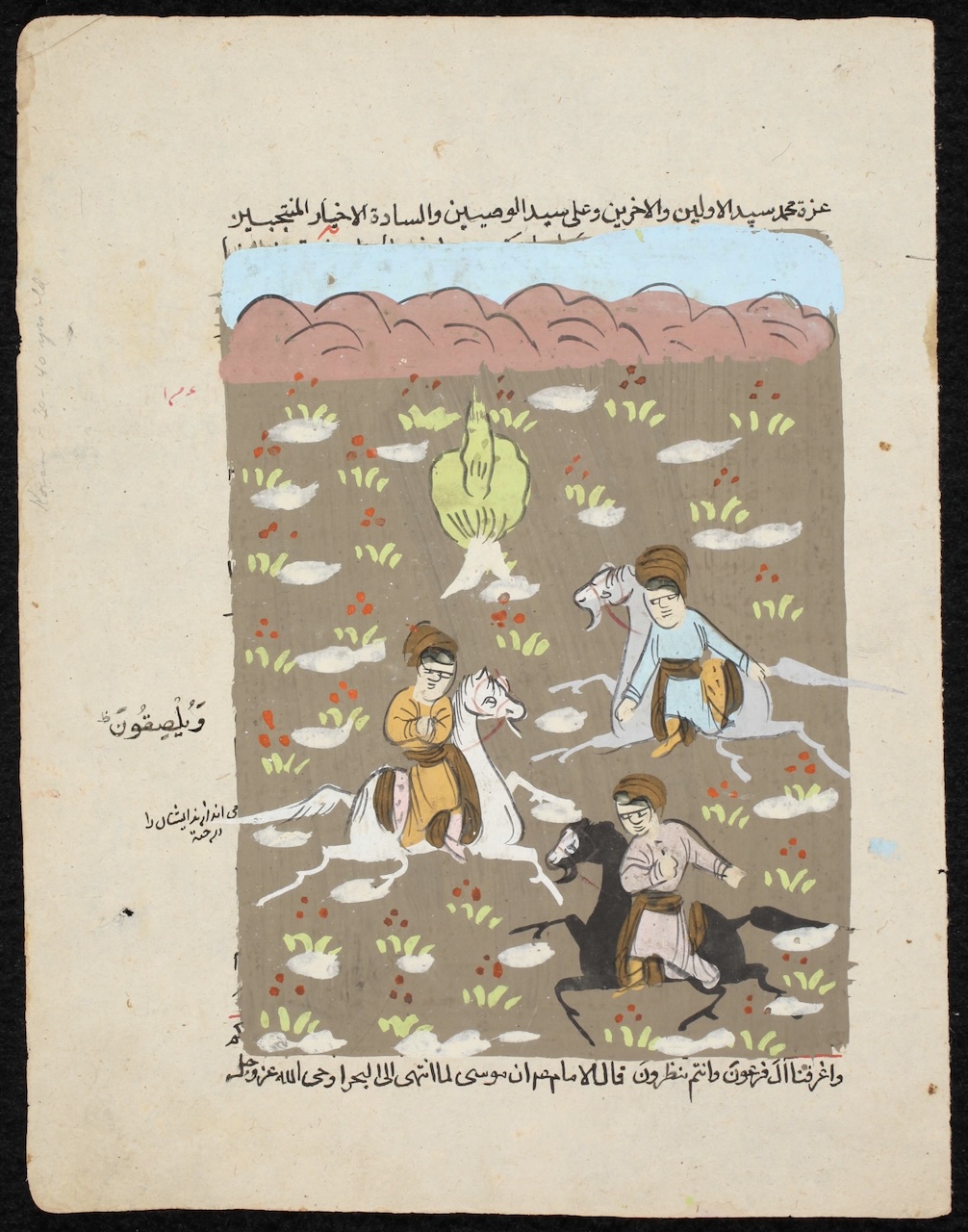

Unrelated Text and Image

Astarābādhī, Alī al-Husaynī.

India, 18th century(?)

Manuscripts are not always completed at one time, by one author, or even with the same idea in mind. These manuscript fragments were completed by two known individuals and are estimated to have been made sometime in the 18th century. The calligraphy is text on Hadith, an Arabic term referring to the reported words and actions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or from his immediate circle. The added illustrations on and next to the text do not correspond to the text and were added at a later date. The unrelated text and image show the continued use of a manuscript over decades, or perhaps, centuries as it is used and reused for different purposes.

Curator(s)

Thomas Meier (CSB+SJU '25), Irma Wyman Intern with special assistance from Dr. Audrey Thorstad

Credits

Special thanks for their contributions to Dr. Audrey Thorstad, who supported the brainstorming, writing, and installing of the materials to the very end; Dr. Matthew Heintzelman, whose guidance and assistance with the materials and HMML’s history made this exhibition possible; Katherine Goertz, who helped to correctly explain the stories of the Arca Artium Art Collection pieces; Dr. Jeremy R. Brown, who provided expertise on the Ethiopian manuscripts; Dr. Daniel Gullo, who helped to contextualize the Malta collections and history of the Malta Study Center; Wayne Torborg, whose help with the new technology helped to finalize the exhibition; Tim Ternes, who provided superb craftsmanship and conservation guidance; and John Meyerhofer, who prepared the online version of this exhibition.