Meet Dr. Ani Shahinian

Meet Dr. Ani Shahinian

Dr. Ani Shahinian, cataloger of Armenian manuscripts, began her work at HMML in 2023. She is also an assistant professor in Armenian Christian art and theology at St. Nersess Armenian Seminary and St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in New York, and has received a DPhil/PhD from the University of Oxford in the UK, an MA from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and a BA from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). Her research interests include questions of what it means to be human in a technological age, focusing on virtue-ethics and the freedom of the human will.

What experiences led you to your work with HMML?

When I look back over the last 20 years, I realize HMML was often present in the background of my journey, even when I was not fully conscious of it. My decade-long study of Armenian Christian texts at UCLA and Oxford for my master’s and doctoral work immersed me in questions about artifacts and manuscripts—their histories, preservation, accessibility, and the importance of digitization. When the HMML opportunity came across my desk, it felt less like a career move and more like a calling. HMML’s mission of “preserving and sharing the world’s handwritten past to inspire a deeper understanding of our present and future” is the purpose and meaning I aspire to in joining HMML, especially for Armenian manuscripts. Some of my role models in Armenian Christian studies, like Norayr Pogharean (1904–1996), devoted their lives to the painstaking, meticulous labor of cataloging manuscripts in print. In taking up this work in digital form, I feel a profound sense of continuity with them—carrying their legacy forward for a new generation, extending the art of cataloging into the digital age.

In many ways I can say HMML found me. My years of research, teaching, and dedication to this field converged with HMML’s announcement of a cataloging position at precisely the moment I was searching for a way to apply my knowledge in tangible, impactful ways. It was as if everything aligned through divine timing. To sum it up, joining HMML was not accidental or the next thing to do—it was providential.

Why does cultural heritage preservation matter to you?

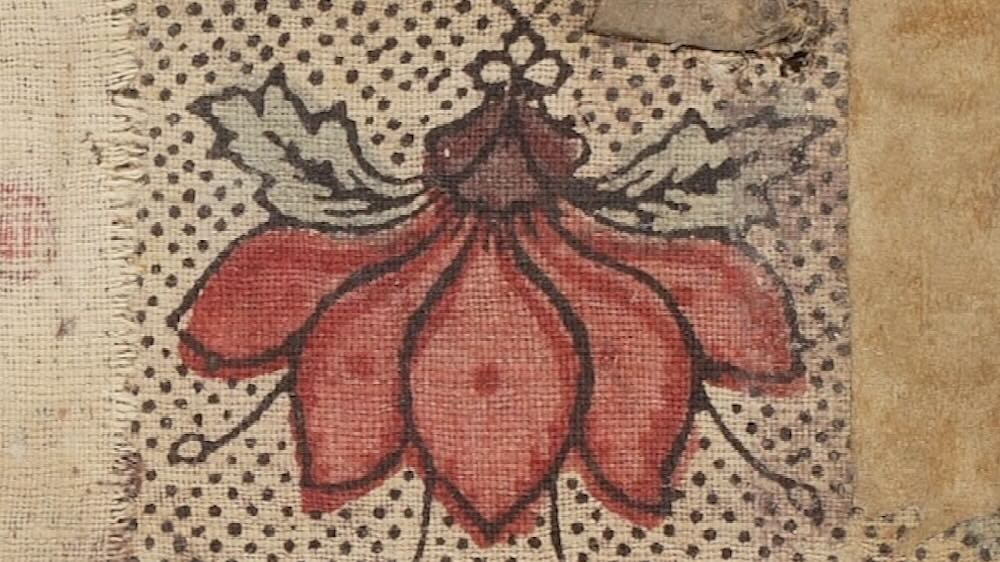

I would like to approach this question with a question: what is cultural heritage? Cultural heritage is the living memory of a people group, the continuity of the memory that is embodied in the peoples’ traditions, texts, rituals, and their material creations including manuscripts, art, illuminations, architecture, and music. Through these treasures, identity and meaning are transmitted across many generations.

From a theological perspective, cultural heritage is more than human memory; it is a form of human participation in God’s creative and redemptive work. Human beings created in the image and likeness of the divine, within their particular cultural settings, are entrusted with the stewardship and the responsibility of this living memory. It bears witness both to human dignity and to God’s presence in history.

A second question worth probing is this: what is the work of preservation itself? Preservation is not a stagnant or inert act, as if the past could be fossilized and sealed away. Rather, it is a dynamic, active engagement. We are born into the culture and heritage of our ancestors—gifts carried to us by our great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents. What we inherit is not meant to remain untouched behind glass; it calls for ongoing engagement and interpretation, a reanimation of enduring principles that speak anew in each generation.

Take a medieval church, for example. It is never only stone upon stone from the 11th century. It is a space entrenched with memory—where generations prayed, resisted, believed, hoped, and created. The art and scripts on its walls are layered with meaning, and when I enter it today in the 21st century, I join that chorus. My prayers are carried into the same current, giving life to the heritage in a way that is true to my time and my community. Preservation is thus a work of renewal as much as it is of safeguarding. Preservation is not simply about protecting artifacts; it is about awakening a new generation to its beauty, transmitting hope, and ensuring that the memory of a people continues to inspire us today.

In essence, the preservation of Armenian Christian cultural heritage matters to me because I have been awakened to see the beauty my ancestors once saw. And having glimpsed that beauty, I feel called to behold it anew and to cast that vision forward—so that my generation and those after me may too be enlightened by its radiance.

What advice would you give to someone who is considering learning another language?

Language is a gateway into another world. When I think, speak, and write in Armenian, I enter a realm that my English-thinking-speaking mind could never fully access—the words, the ideas, even the very structure of meaning itself open a horizon that otherwise remains closed. Every language carries within it layers of memory, culture, and histories of human beings in unique way.

If someone is seeking to learn a new language, my first advice would be to inquire more about what world they long to explore more deeply. Choose that language—the one that calls to you with its history, its culture, its people—and commit yourself to study it faithfully. Books and classes will give you a foundation, but if you have the opportunity, live among those who speak it. Let the idioms, humor, and nuances become familiar to you. Allow the rhythms of their daily life—the way people greet, argue, pray, or sing—to enrich how you think. In the end, learning a language is not only about words and grammar; it is about learning to see the world through another set of eyes. It enhances one’s perspective and perception.

If you could choose to visit any collection in the world—where HMML has worked or has yet to work—which would you choose, and why?

Over the years, almost seamlessly, my travels have been accompanied by deep curiosity, driving me to explore not just texts, but the people, cultures, and landscapes from which many of the manuscripts I’ve worked on emerged. I have had the privilege of working with some of the most treasured collections preserved in the great Armenian Christian centers around the world. As a lifelong investigator of all things meaningful, I have sought out the places where manuscripts endured against the odds. One such place I hope to visit is Bzummār Monastery in Lebanon, which safeguarded many Armenian manuscripts that survived the Genocide in the late Ottoman Turkey, in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, my travels took me to Nicosia, Cyprus—a city once home to a vibrant Armenian Christian community for hundreds of years. Only later did I realize that the manuscripts I began cataloging for HMML in the summer of 2025 were originally composed there and are now preserved at the Armenian Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia in Anṭilyās, Lebanon—a site I hope to visit in the near future.

Most recently, in September 2025, I was surprised by joy, visiting the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul as well as neighborhoods tied to the survival of manuscripts after the Armenian Genocide. I have been cataloging many of the manuscripts in these collections, which were digitized by HMML in 2005–2009 (learn more about this history). The neighborhoods I visited included Balat, Galata, Ortaköy, and Kumkapı. Kumkapı is where the Patriarch’s Collection is housed today, alongside the treasures of the Azgayin Matenadaran (the National Library) which no longer exists, erased by the remapping of the city and the construction of roads over its place. To journey among these places was to stand in continuity with the endurance of a people and the treasured manuscripts that carry their memory and faith forward.

What book should everyone read?

This may not be the obvious choice for our generation, but the book that has shaped my life and sustained a decades-long scholarly inquiry is the Bible.

The Bible is not simply a book; it is a library of books. Within its pages, I first encountered the beauty of poetry and prose, history, the chaos of drama, the power of symbols, the transparency of epistolary compositions, the depth of imagination, and the complexities of human relationships—all woven together in one place. Today, I see the impact of the Bible on thousands of years of manuscript tradition—almost every page I catalog has God-breathed words (the Armenian rendering of the Bible is Աստուածաշունչ, “God’s Breath”) on the page. So, in a way, I have been preparing for my HMML position since I opened the Bible in the Classical Armenian many decades ago.

As my studies deepened, I discovered that many of the scholars I most respect had come to recognize the importance of Classical Armenian (գրաբար) precisely through their broader biblical studies. When they probed the depths of the biblical world, it led them to the Armenian Bible—and now I understand why. Many treasures of biblical exegesis, hermeneutics, theology, and literature have been preserved in Classical Armenian, as the HMML manuscript collections bear witness. It all started with Mesrop Mashtots‘, in the 5th century, who tirelessly labored to create the Armenian alphabet to translate the Bible from Syriac and Greek into Armenian, an innovation that has changed the course of Armenian and Christian history forever.

The very first words ever written in Armenian came to be Scripture—Ճանաչել զիմաստութիւն եւ զխրատ, իմանալ զբանս հանճարոյ (“To know wisdom and counsel; to perceive the words of understanding,” Proverbs 1:2). As a young child and later a young scholar I had the innate pull—that if I want wisdom and understanding I ought to read the Bible. It remains, for me, the wellspring of inquiry, beauty, and vision.