Arabian Nights Of The Christian East

December 20, 2021

Arabian Nights of the Christian East

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Following a Story Time theme, Dr. David Calabro shares this tale from the Eastern Christian collection. This is Part 1 of the story. Read Part 2 now.

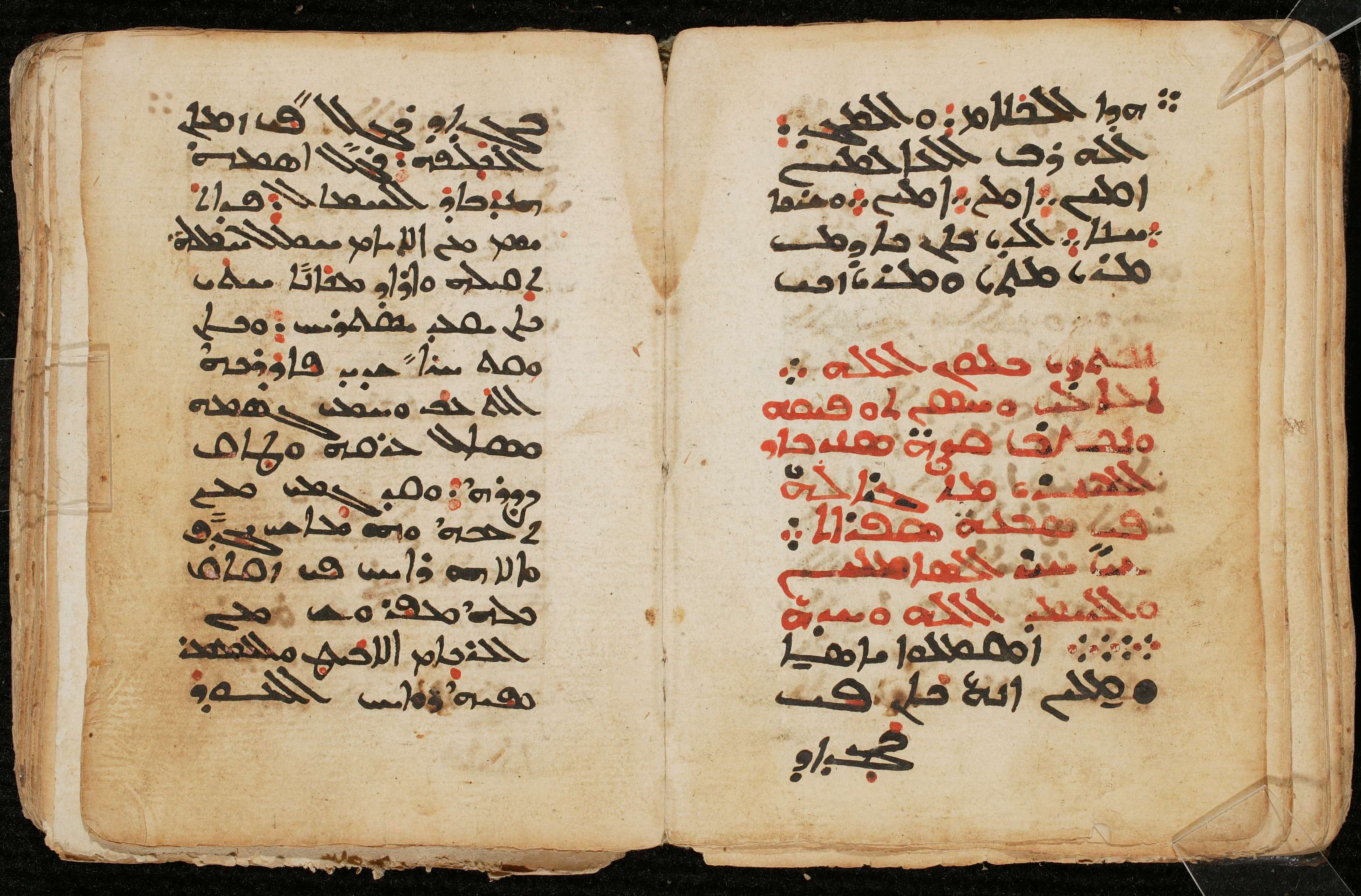

On a shelf in the Syriac Orthodox Church of Saint George in Aleppo is a manuscript copied in Arabic Garshuni (Arabic written in Syriac script) by Ḥannā, a monk of the Monastery of Mar Mattay near Mosul, in 1694.

Most of the contents of this manuscript are unambiguously Christian: assorted prayers, the Colloquy of Moses on Mount Sinai, a homily by Ephrem the Syrian on the Resurrection and the parting of the soul from the body, a short version of the Arabic Apocalypse of Peter. But after copying these texts, Ḥannā writes:

“We begin by the help of God, may he be exalted, and the goodness of his blessing, to write the story of Sindbad the Sailor and what happened to him on his seven voyages, a thing that will amaze those who hear.” (SOAA 124 M, folios 85v, 164rv)

Here, then, we have a rare early copy of the famous tale of the “Seven Voyages of Sindbad.” This tale (actually a cycle of tales within a frame story), although originally independent, was incorporated in the early 18th century into the collection of Arabian Nights stories known as the Thousand and One Nights, which divides each story into nightly episodes placed within a larger frame story of King Shahriyār and his wife Shahrazād.

Throughout its history, the class of entertaining stories known today as Arabian Nights has been a porous category. The stories have circulated independently; they’ve been gathered in collections like the Thousand and One Nights; and, in every form, they’ve traveled across geographical, cultural, and religious boundaries.

Tales in the tradition of the Arabian Nights had a wide circulation in Christian communities in the Middle East. In general, they circulated as independent stories nestled among other texts, not as part of the Thousand and One Nights. Ḥannā’s copy of Sindbad, included in a book of religious texts, is one such example. Many other examples occur in manuscripts digitized by HMML (see Dr. Vevian Zaki’s editorial “Want to Marry the Princess? Know thy Bible!”).

Arabian Nights stories in Christian manuscripts digitized by HMML:

| Story title | Arabian Nights tale number | HMML manuscripts (in order of date) |

|---|---|---|

| “Ebony Horse” | 103 | SOAA 00121 K (1779), CFMM 00297 (1823), CFMM 00306 (17th century?) |

| “King Azadbakht and the Ten Viziers” | 268 | MBM 00386 (1636), CCM 00013 (1719), CPB 00164 (1770), GAMS 01250 (1860), CFMM 00306 (17th century?), OBA 01283 (17th century?), SCAA SL09 63 (17th century?), USJ 01428 (19th century) |

| “King Jalīʻād of Hind and His Vizier Shīmās” | 236 | OBA 01047 (1755), USJ 01428 (19th century) |

| “Linguist-dame, the Duenna, and the King’s son” | 411 | SOAA 00121 K (1779), CFMM 00297 (1823), MBM 00209 (1856), OBA 00534 (18th century?) |

| “Masrūr and Zayn al-Mawāṣif” | 232 | CCM 00018 (1610), MBM 00406 (18th century?) |

| “Seven Voyages of Sindbad” | 179 | SOAA 00124 M (1694), CPB 00164 (1770), MBM 00209 (1856), CFMM 00306 (17th century?), USJ 01428 (19th century) |

| “Sulayman Shah and His Niece” | 278 | CPB 00164 (1770) |

| “What Befell the Fowlet with the Fowler” | 414 | MBM 00209 (1856), USJ 01428 (19th century) |

These manuscripts provide abundant testimony to the power of an entertaining narrative. Rather than propounding a specific religious doctrine, most Arabian Nights tales either teach general moral values or aim simply to entertain. Thus, they flow easily between religious traditions. After all, regardless of one’s religious background, a good story is still a good story.

Eastern Christian transmitters played a vital role in bringing some of the tales that we now associate with the Arabian Nights to a Western audience in the 18th century. The popularity in the West of the Thousand and One Nights began with the French translation of Antoine Galland, of which the initial volumes appeared in 1704. The tales were so popular, and the exaggerated title Thousand and One Nights so alluring, that Galland and others supplemented the collection with stories that were not originally part of the Thousand and One Nights.

These additional stories, known today as “orphan tales,” included some stories that have proven most popular and today are most readily associated with the Thousand and One Nights: “Aladdin and Wonderful Lamp,” the “Ebony Horse,” “Prince Ahmad and the Fairy Peri Banu,” “King Azadbakht and the Ten Viziers,” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.” The “Seven Voyages of Sindbad” is not usually counted among the orphan tales, since Galland had already incorporated it into the first volume of his collection in 1704.

Galland’s immediate source for his orphan tales was a Maronite Christian man from Aleppo named Ḥannā Diyāb (a different Ḥannā than the monk who copied “Sindbad” in the Aleppo manuscript mentioned above). In later volumes of the Thousand and One Nights, more stories were added by Diyūnīsiyūs Shāwīsh (known as “Dom Chavis”), a priest and monk from the Middle East who was residing in Paris at the time.

About a century after Galland, Maximilian Habicht’s Breslau edition of the Arabic text of the Thousand and One Nights, which included some of the orphan tales, was published. His edition was based on copies of the stories made by his Tunisian Jewish friend Mordecai ibn al-Najjār, who used manuscripts located in Paris, some of which were of Christian provenance.

What is still poorly understood is the history of these stories in Christian communities before their transmission to the West. Some of the tales are found in Christian manuscripts that were copied before the tales appeared in the West, such as the 1694 Aleppo manuscript mentioned above. This fact may suggest the tales were part of a longstanding Eastern Christian tradition. Some other tales are known to have circulated as independent Christian narratives for centuries before becoming associated with the Arabian Nights, such as the stories of Ahiqar (Arabian Nights tale number 409) and Susanna (tale number 128).

Religious and chronological indicators within some Arabian Nights stories suggest that the stories have crossed back and forth between religious communities, gathering details from one or the other community with each pass. In that way, the stories are not unlike Sindbad himself, traveling from one place to another, gathering treasures of all kinds along the way.