The Travels Of The Ebony Horse

The Travels of the Ebony Horse

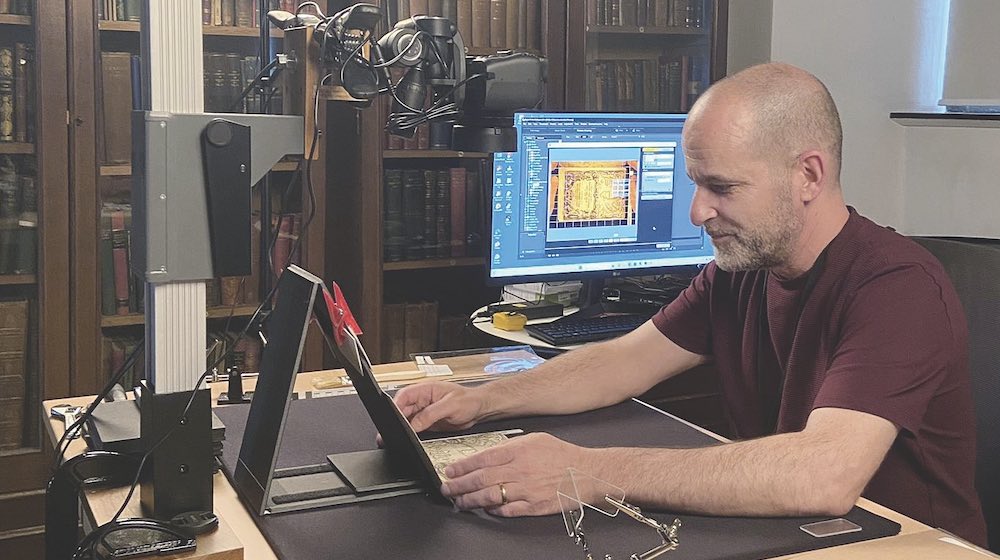

December 23, 2021This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Following a Story Time theme, Dr. David Calabro shares this tale from the Eastern Christian collection. This is Part 2 of the story. Read Part 1 now.

The history of Arabian Nights stories in Christian communities is still imperfectly understood. We do know that Eastern Christian transmitters played a vital role in bringing some of the tales we now associate with the Arabian Nights to a Western audience in the 18th century. Translations of collections such as the Thousand and One Nights helped popularize the genre in the West, and even introduced new stories to the beloved book. One such example is the story of the “Ebony Horse.”

The “Ebony Horse” tells the tale of a Persian king who loved gadgets. On the occasion of a festival, a crafty sage (or, in some versions, a group of three sages) comes to visit the king. The sage presents the king with an ebony horse that will fly up into the air with the flip of a switch on the horse’s neck.

The king is so impressed with this new toy that he offers the sage his daughter in exchange for it. However, her brother, the prince, arrives on the scene to beseech the king on her behalf. The prince himself becomes curious about the horse and tries to ride it. But, unfortunately, once he is in the air he realizes that he does not know how to make the horse descend, and he helplessly flies away. The king, incensed at the sage (and, no doubt, frustrated about losing the horse), has the sage thrown into prison.

Meanwhile, the prince wisely ascertains that since there are two switches on the horse’s neck—one of which makes the horse ascend—the other must make it descend. He finally alights on the roof of a palace in a country he does not recognize. He fearlessly enters the palace, where he finds a sleeping princess and falls in love with her at first sight.

The prince ends up taking the princess with him on the flying horse back to Persia. He leaves the princess and the horse in the garden outside his father’s palace and goes to find his father. The king is so overjoyed at his son’s return (and, no doubt, at the return of the horse) that he releases the sage from prison. The vengeful sage, however, goes immediately to the garden. He meets the princess and persuades her that he was sent by the prince to conduct her to the king. As soon as he has the princess with him on the magic horse, he flies away with her and takes her to a faraway land. There they meet a king who disposes of the sage and takes the beautiful princess for himself. The distressed princess falls sick, and none of the king’s doctors can restore her to health.

After many travels, the prince hears of an ailing princess and knows that he has at last found his beloved. Disguised as a doctor, he visits the princess, who immediately revives upon recognizing her true love. The two fly back to Persia on the magic horse and are married.

A Traveling Tale

There are several versions of the “Ebony Horse,” each of which has different details and nuances and help trace the history of the story’s transmission.

The earliest known version is found in the Hundred and One Nights—a collection of stories similar to the Thousand and One Nights, but dating to the 10th century or earlier. This version of the “Ebony Horse” contains almost no specific information about the places or time period in which the story is set, but the story does open in Persia, and the three gift-bearing sages come from India, Greece, and Persia (the sage from Persia is the one with the ebony horse).

At least two major versions of the “Ebony Horse” have Christian origins. One version, transmitted by a Maronite man from Aleppo named Ḥannā Diyāb, was published in French translation in the second volume of Antoine Galland’s Les mille et une nuits in 1704.

In this version, all of the action takes place in Persia and India; the latter seems to function as the quintessential land of mystery and adventure. The story opens in the Persian city of Shiraz, where the court is said to have been at the time the story takes place. The king’s name is not mentioned, but the prince has a typically Persian name, “Firouz Schah” (according to the spelling in Galland’s French translation). The sage, who comes alone, is said to be from India. The prince’s beloved is the princess of Bengal, and the foreign land to which the Indian sage takes the princess is Kashmir.

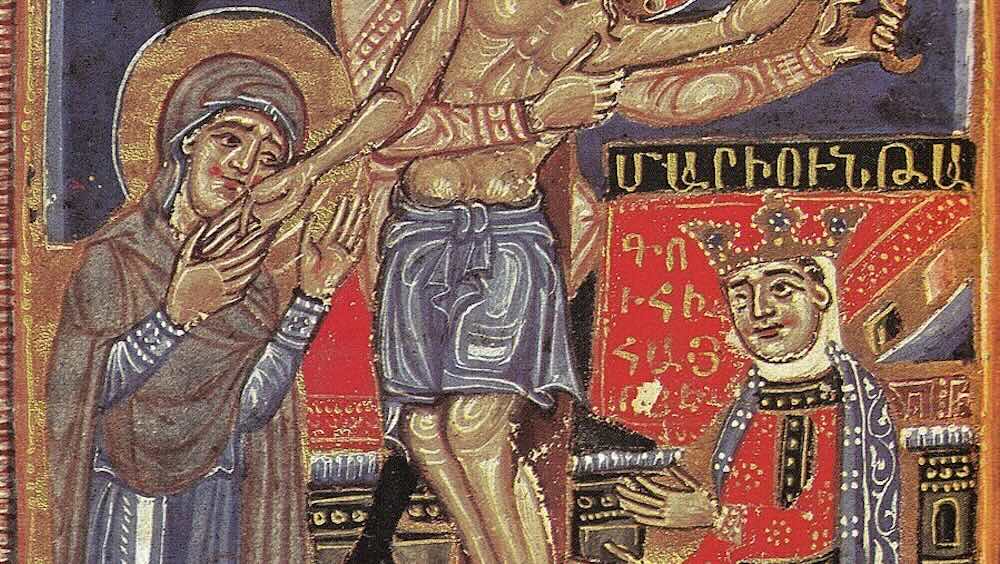

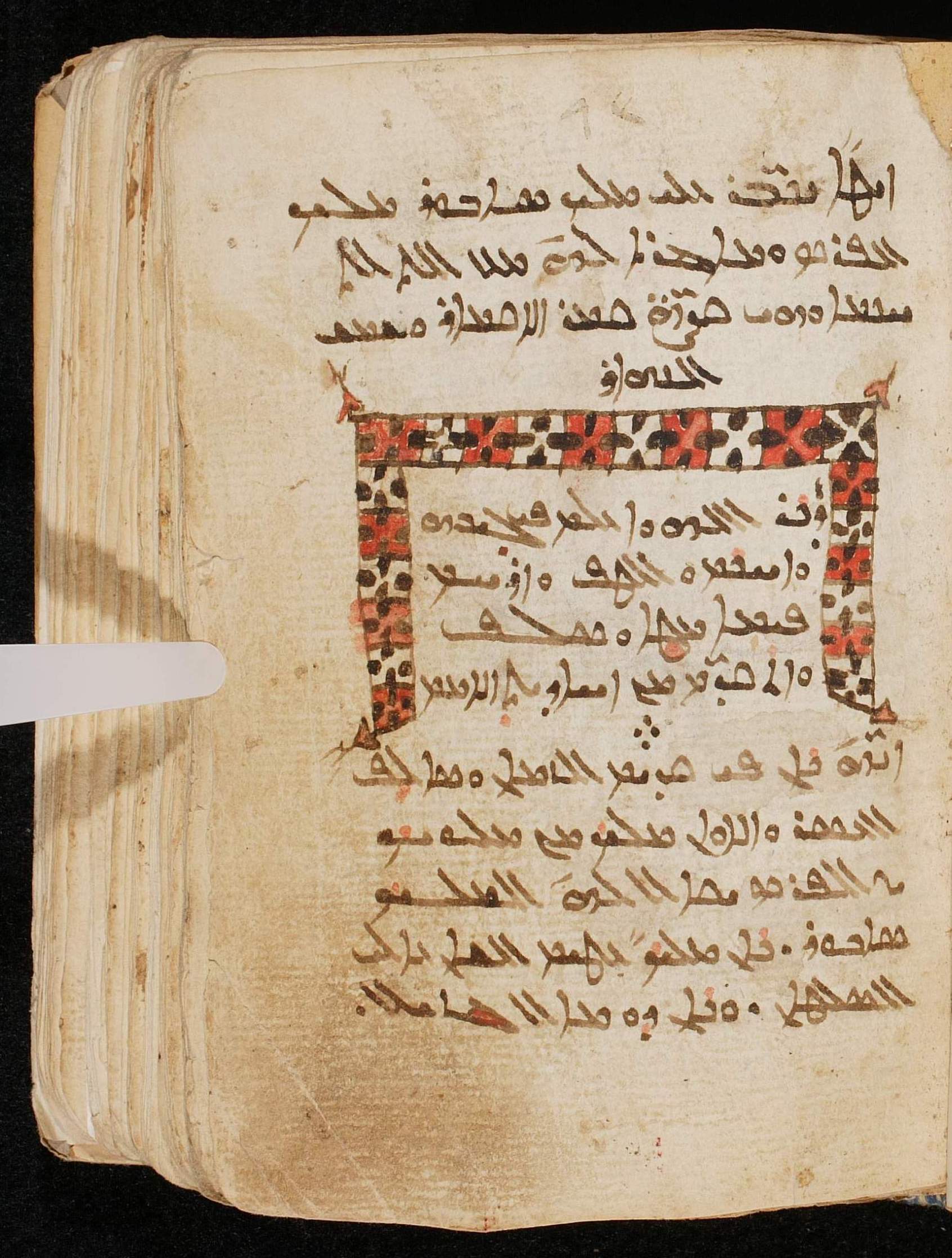

A second Christian version was published in Arabic by Maximilian Habicht. This version agrees precisely with a manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscrit arabe 3637, which was copied by a Syriac Christian in 1772. Furthermore, three Christian manuscripts digitized by HMML have exactly the same version of the story: CFMM 00306, CFMM 00297, and SOAA 121 K.

In this version, the king of Persia is identified as Sābūr (Shapur). As in the Hundred and One Nights, there are three sages, who come from India, Greece, and Persia, and the one from Persia is the one with the ebony horse. The father of the princess—the king of the palace upon whose roof the prince descends—is named Qayṣar (Caesar), implying that the foreign land is Rome or Byzantium. (Given the historical conflict between Shapur II and the Byzantine empire, one may sense here a sort of West Side Story, with the son of Shapur courting the daughter of Caesar.) And when the Persian sage abducts the princess, he takes her to the land of China.

It is typical of literary folktales like the Arabian Nights that elements of the narrative point symbolically to what the story itself is doing. In the “Ebony Horse,” for instance, the three sages bring mechanical wonders from their civilizations (India, Greece, and Persia) to the king, just as the story itself uses literary devices from multiple traditions. The dominant motif of this story is, of course, the ebony horse, which magically transports riders to foreign lands. Similarly, the story transports readers as if by magic into a world of fantastic wonders. And the story itself has traveled across time, space, and religious tradition. Thus, the “Ebony Horse” embodies on many levels the power of entertaining narrative to cross borders.