The Mysteries & Rhythms Of Nature, Seasons, And Time In The Armenian Liturgical Calendar

The Mysteries & Rhythms of Nature, Seasons, and Time in the Armenian Liturgical Calendar

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Dr. Ani Shahinian has this story about Weather.

Rhythms in Nature

Have you ever wondered about the significance of the cycles of a day, week, month, and year? What is the basis for accurate timekeeping? Imagine a world before the adoption of the 24-hour clock. How does one measure a day?

Cycles of night and day have been a subject for contemplation from the beginning of time. For example, the opening of the ancient text of Genesis in the Hebrew and Christian scriptures (Genesis 1–3) touches at the heart of the very elements of light and darkness: night and day as part of the acts of creating order in the midst of chaos—a place and space where human life is made possible.

In the progress of modernity, we individual beings are rarely required to calculate the hours and the days or to be cognizant of their process. These complex cycles have been standardized across the globe, and we wake up each day to the time on our clocks and with the weekly, monthly, and yearly calendars set in place for us.

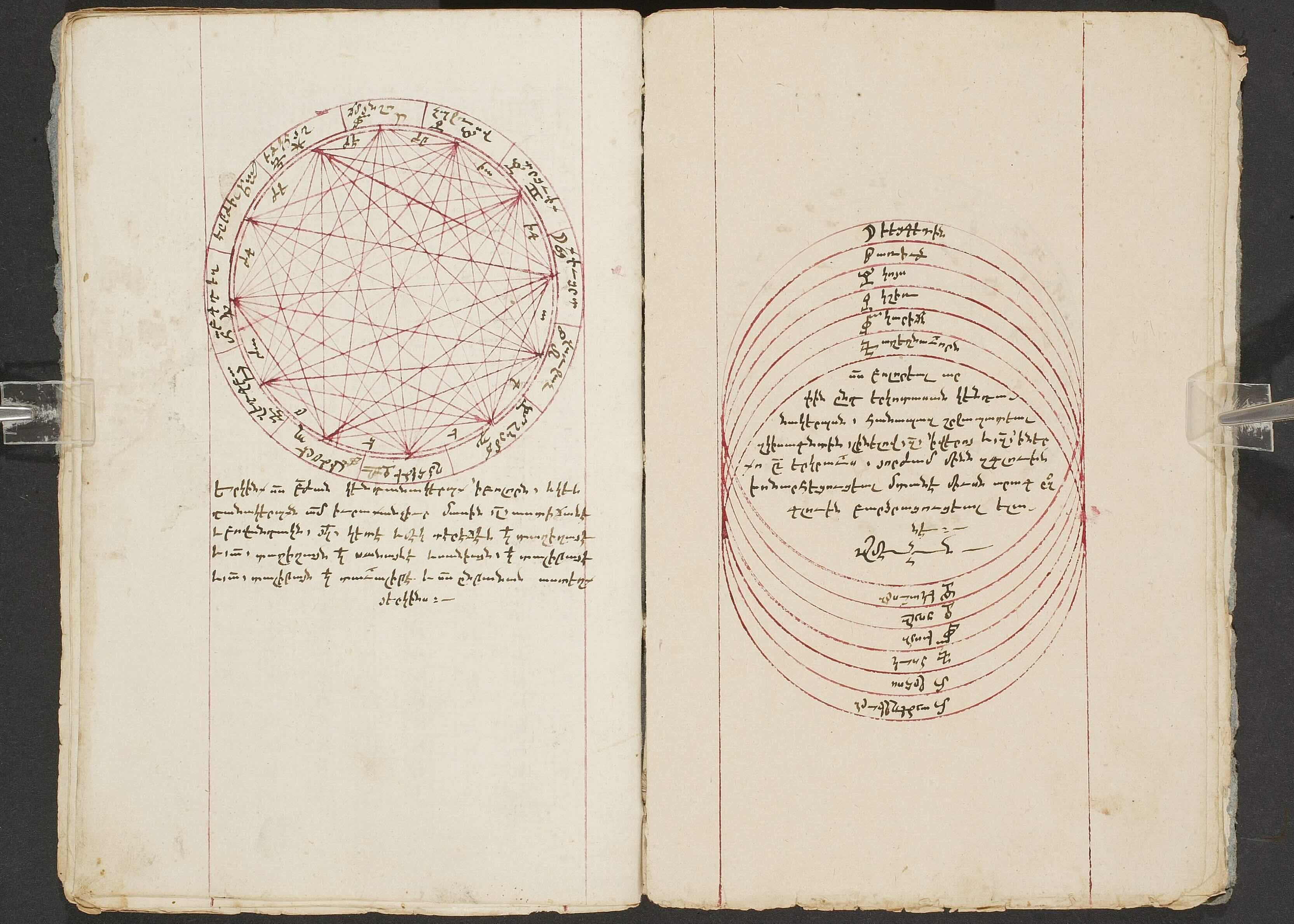

In history, three types of calendars have emerged as the most common: lunar, solar, and lunisolar. The discoveries and efforts of the ancients led to the current standards that we use with ease. They relied on nature, seasons, the skies, stars, planets, constellations, and an understanding of the sun, moon, and tides to calculate and measure the days, equinoxes, and solstices and to predict the seasonal behavior of nature. But not only this. For the ancients, the physical world was intricately connected to the physical reality of human existence, survival, and flourishing. In other words, the natural world and the embodied human soul were connected, somehow.

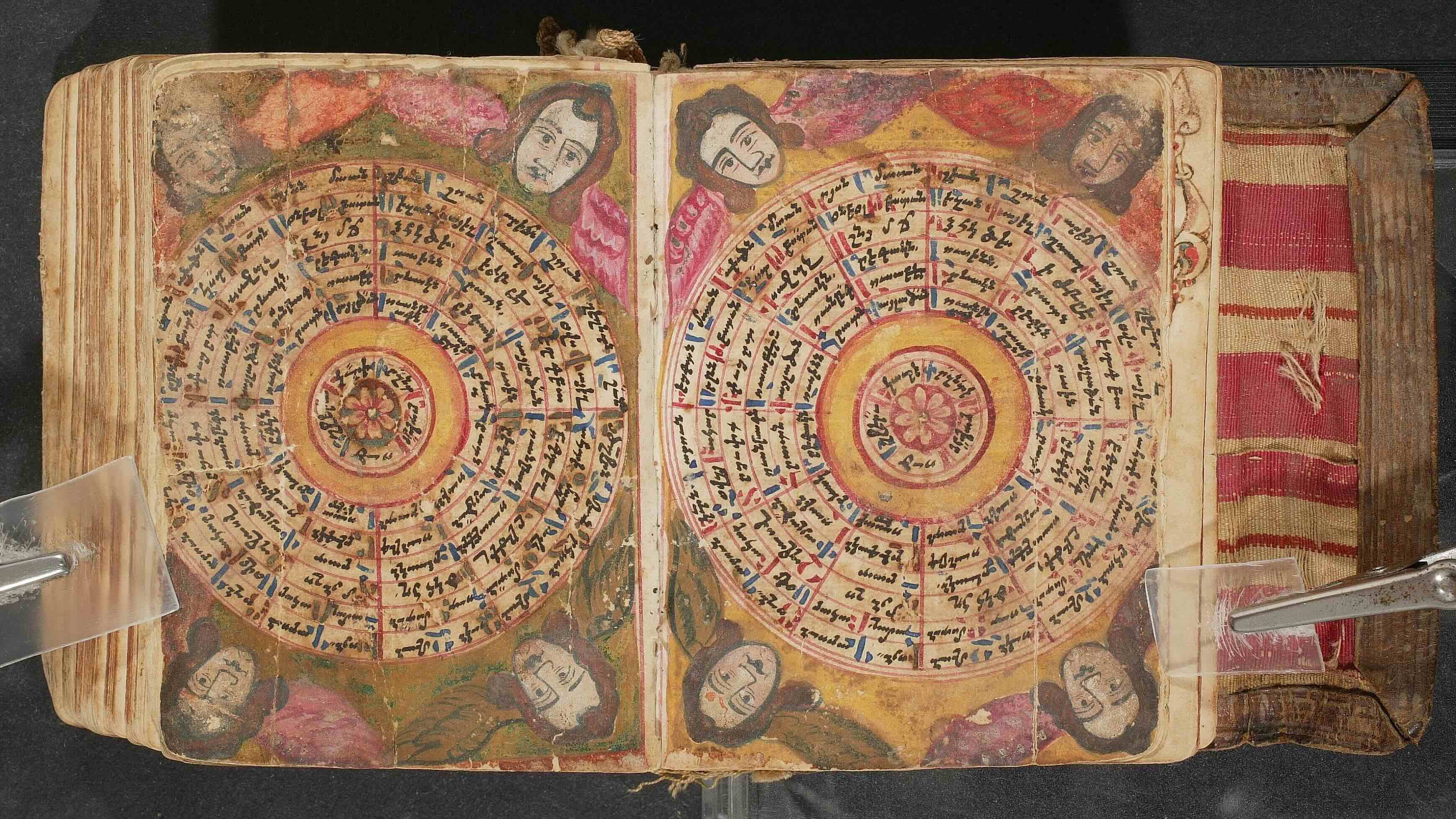

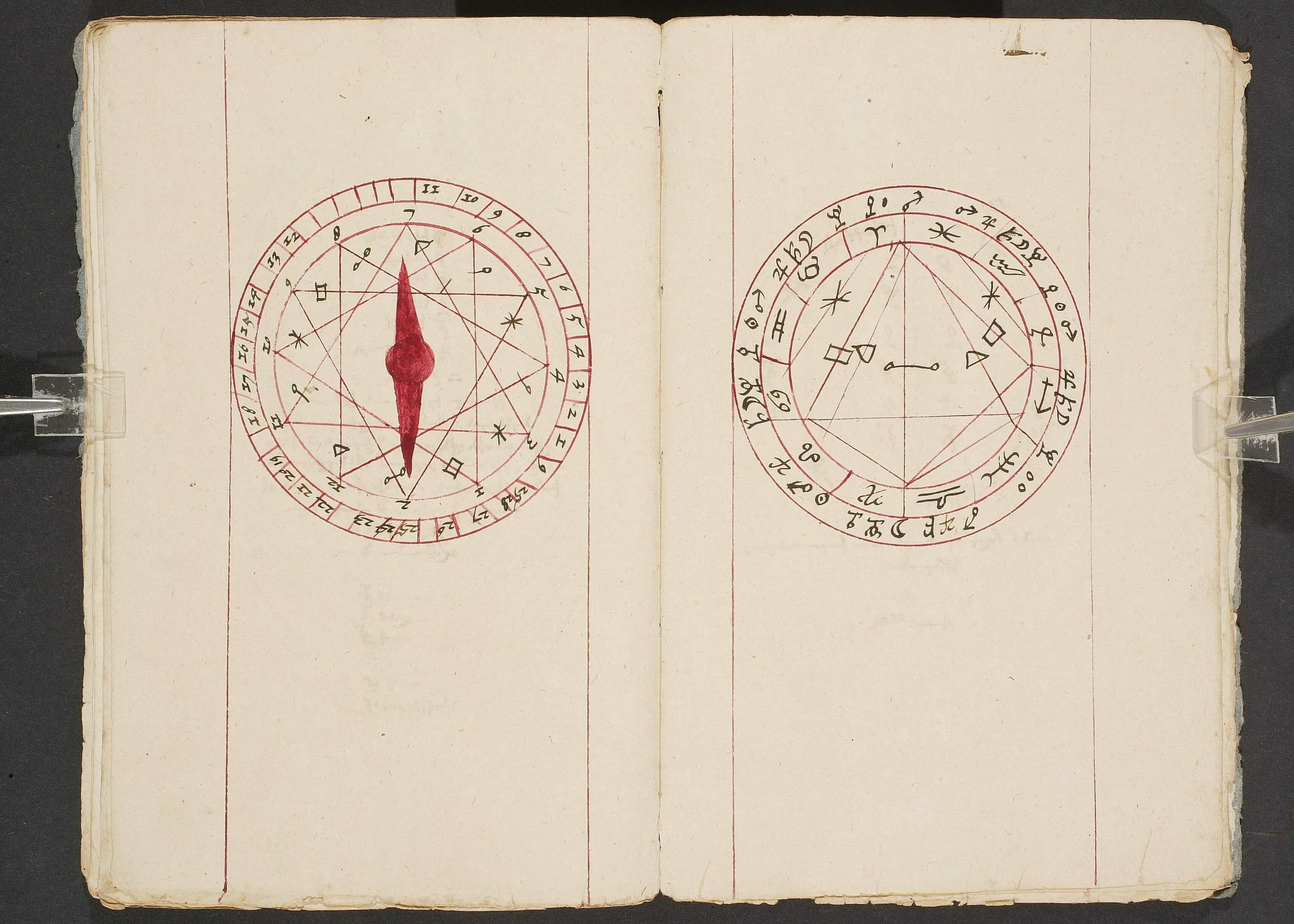

The long process and evolution of the calendar is observed in Armenian medieval manuscripts. The calculation and development of the Armenian calendar (tōmar and the parzatōmar) harmonized human experience with natural realities. Armenian vardapets (Church teachers for hearts and minds) Yovhannēs Sarkawag (c. 1050–1129) and Yakob Ghrimets‘i (1360–1426), were two main commentators on the Armenian tōmar, where they unfolded the treasures of the Armenian calendar with insights from the physical and natural worlds.

The Building Blocks of the Armenian Liturgical Calendar

In the Armenian Christian tradition, one way that physical and spiritual worlds are brought together is in the arrangement of the liturgical and festal calendars through the lunisolar (moon and sun) calendar.

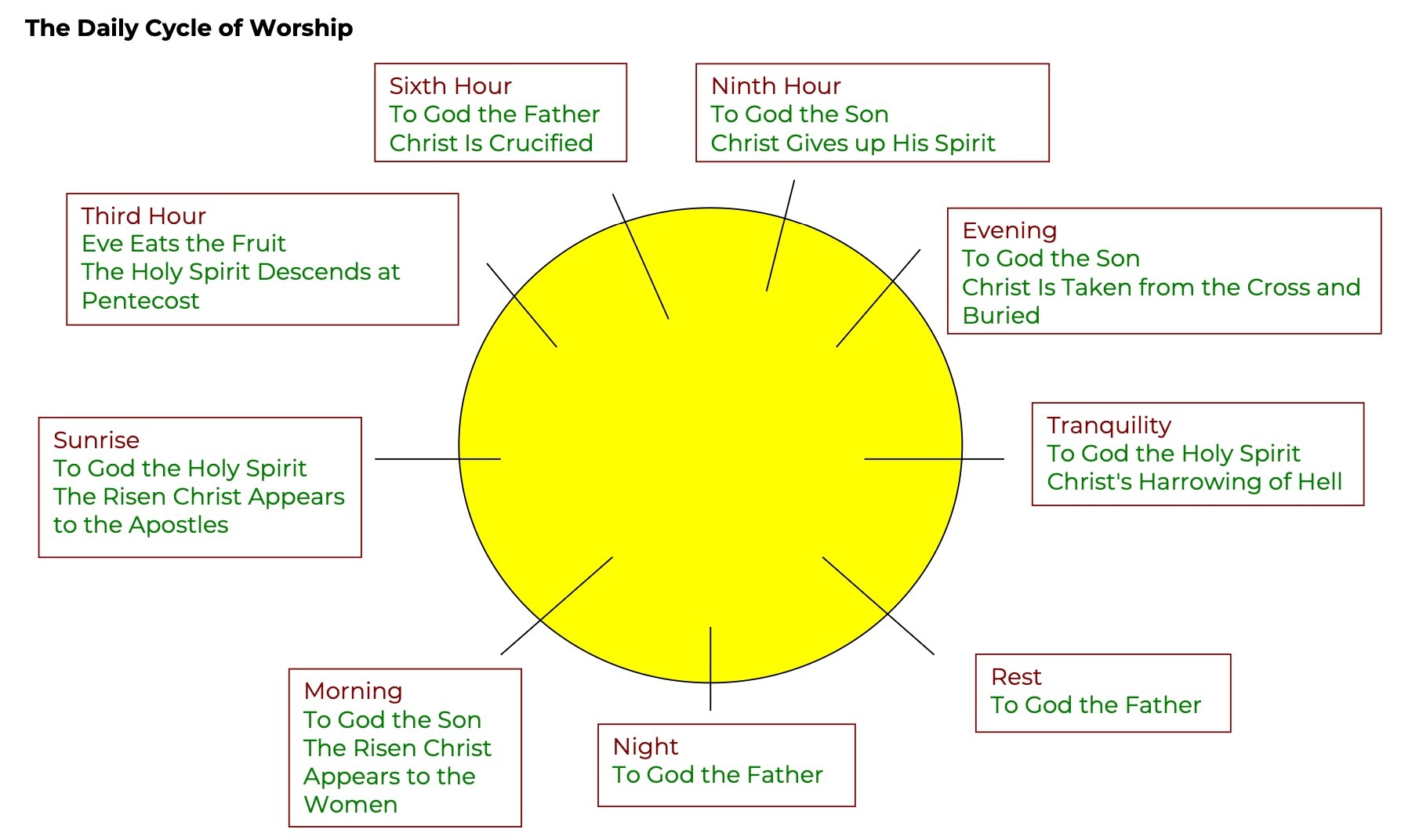

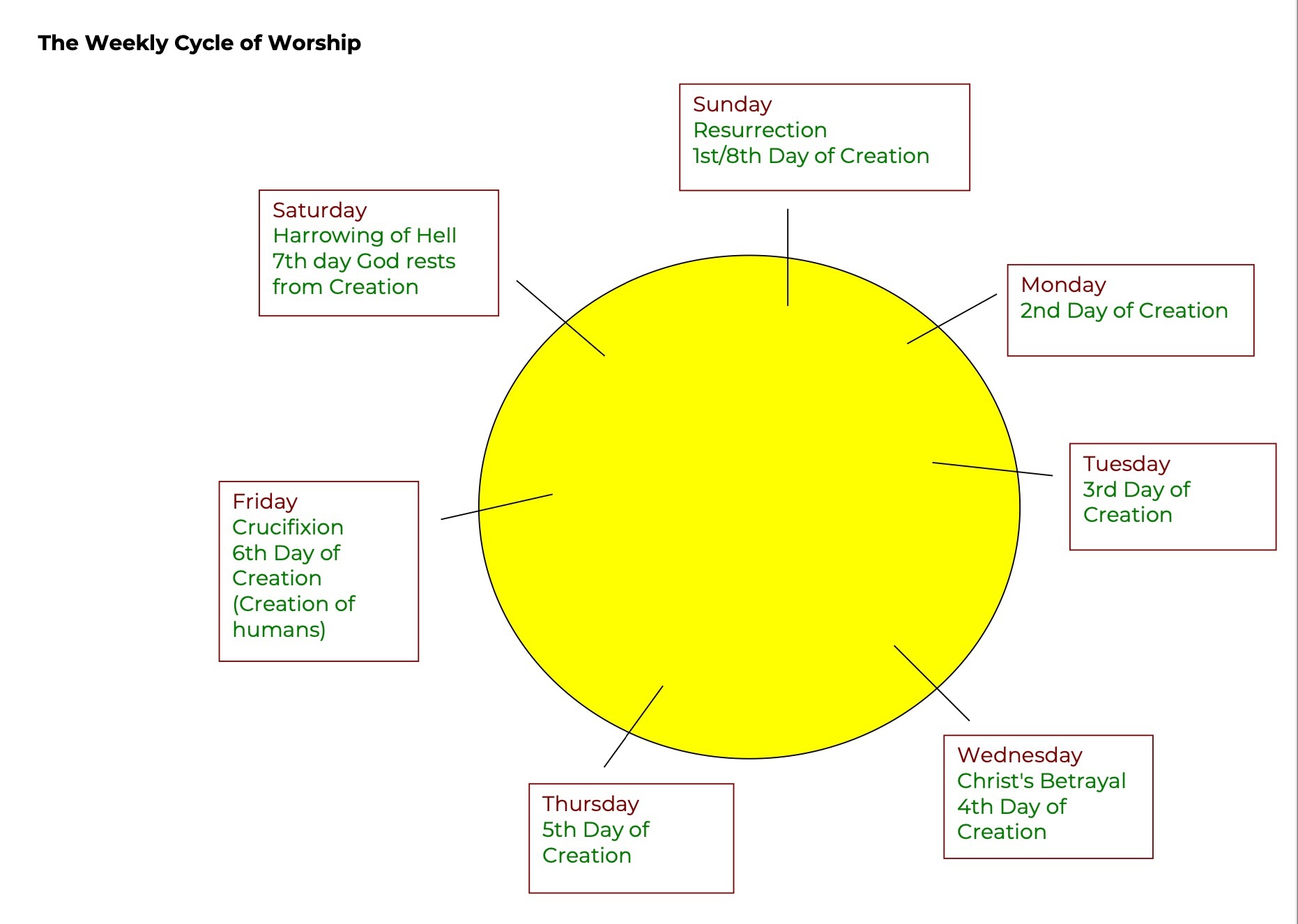

The Armenian liturgical calendar positions the daily/hourly, weekly, and yearly cycles in a way that is not independent of natural/physical cycles. Rather, the calendar itself goes through the cycles. For example, beginning with sundown in the evening, the daily prayers are arranged with meditative prayers—psalms, sharakans (hymns), and scriptures—to position the human soul to face the dark night. Similarly, the morning liturgical services positions the soul to face all the challenges one may face in the day ahead.

Daily cycle of the Armenian liturgical calendar, capturing and tracing the movement of light across a day, correlating each hour to the life of Christ on earth. Chart credit: Dr. Roberta Ervine, St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, Armonk, NY.

Weekly cycle of the Armenian liturgical calendar, correlating each day of the week with creation and Passion Week. Chart credit: Dr. Roberta Ervine, St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, Armonk, NY.

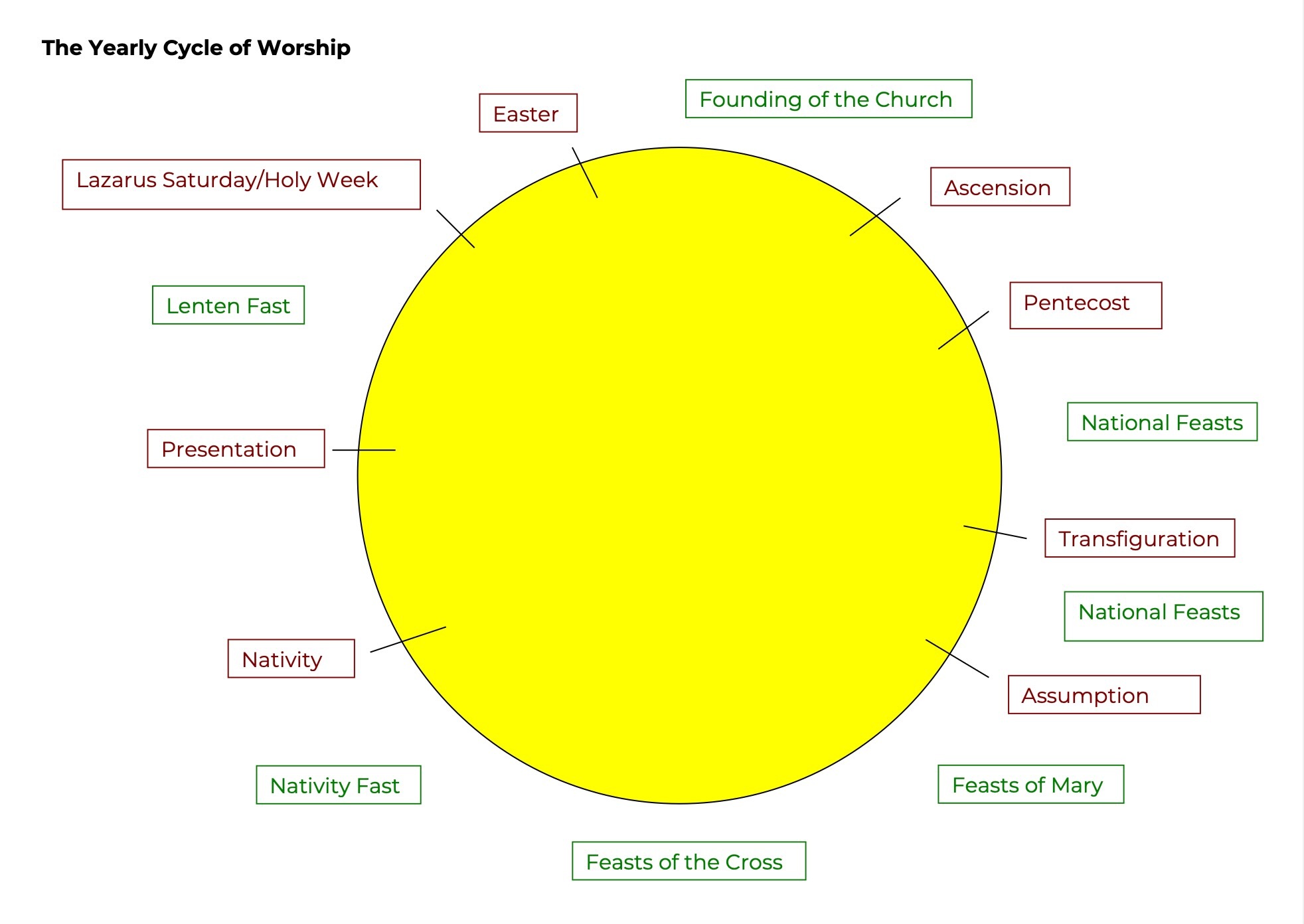

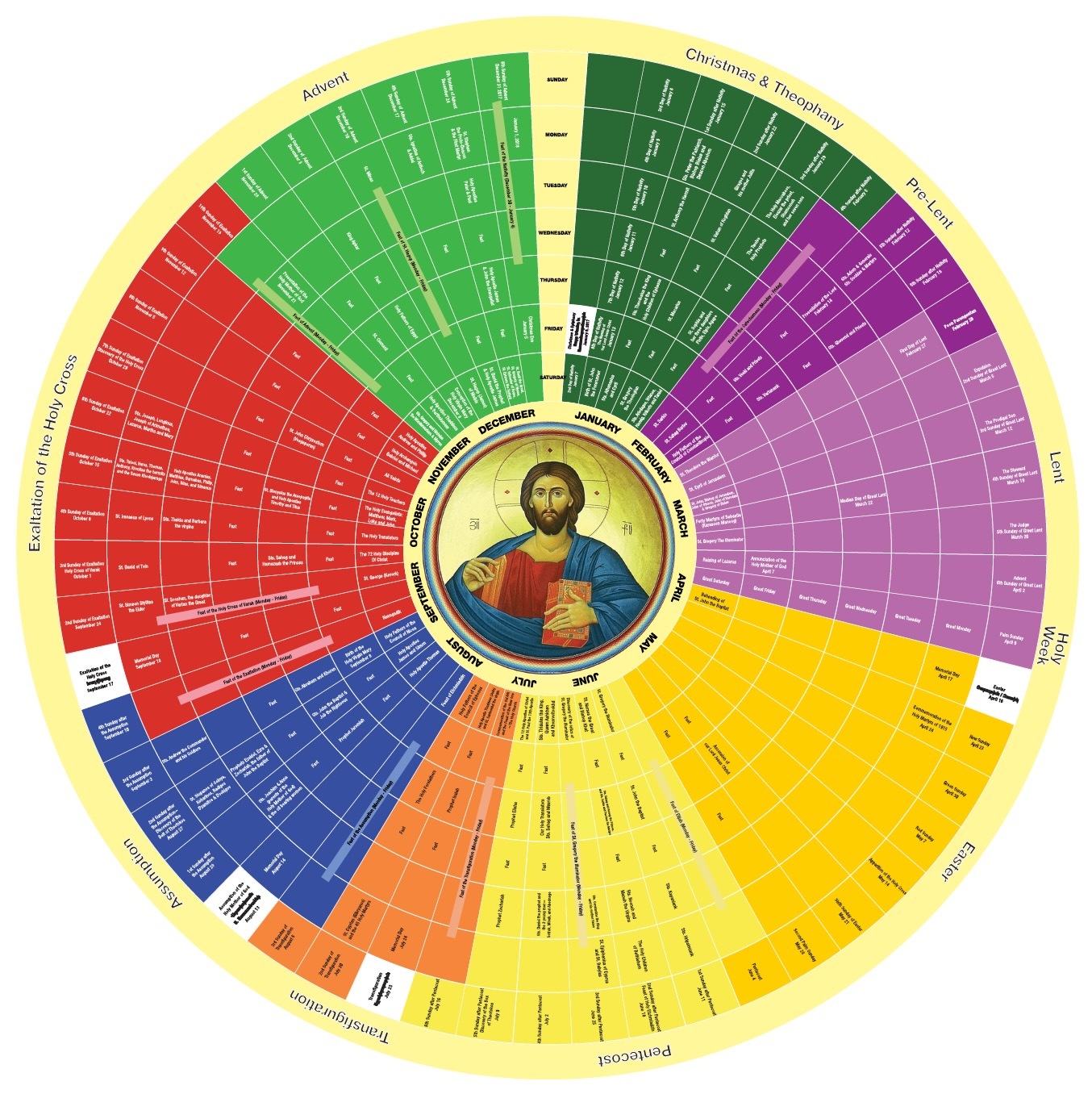

Yearly cycle of the Armenian liturgical calendar. The year begins with the fixed dated of Nativity, the birth of Christ. It moves clockwise to Easter, a date that is not fixed, but changes according to the lunar and solar calendar each year. The date of Easter then determines the Lenten season for fasting, the feast of Pentecost, Transfiguration, and others. The cycle ends with the Feast of the Cross in the month of September. Chart credit: Dr. Roberta Ervine, St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, Armonk, NY.

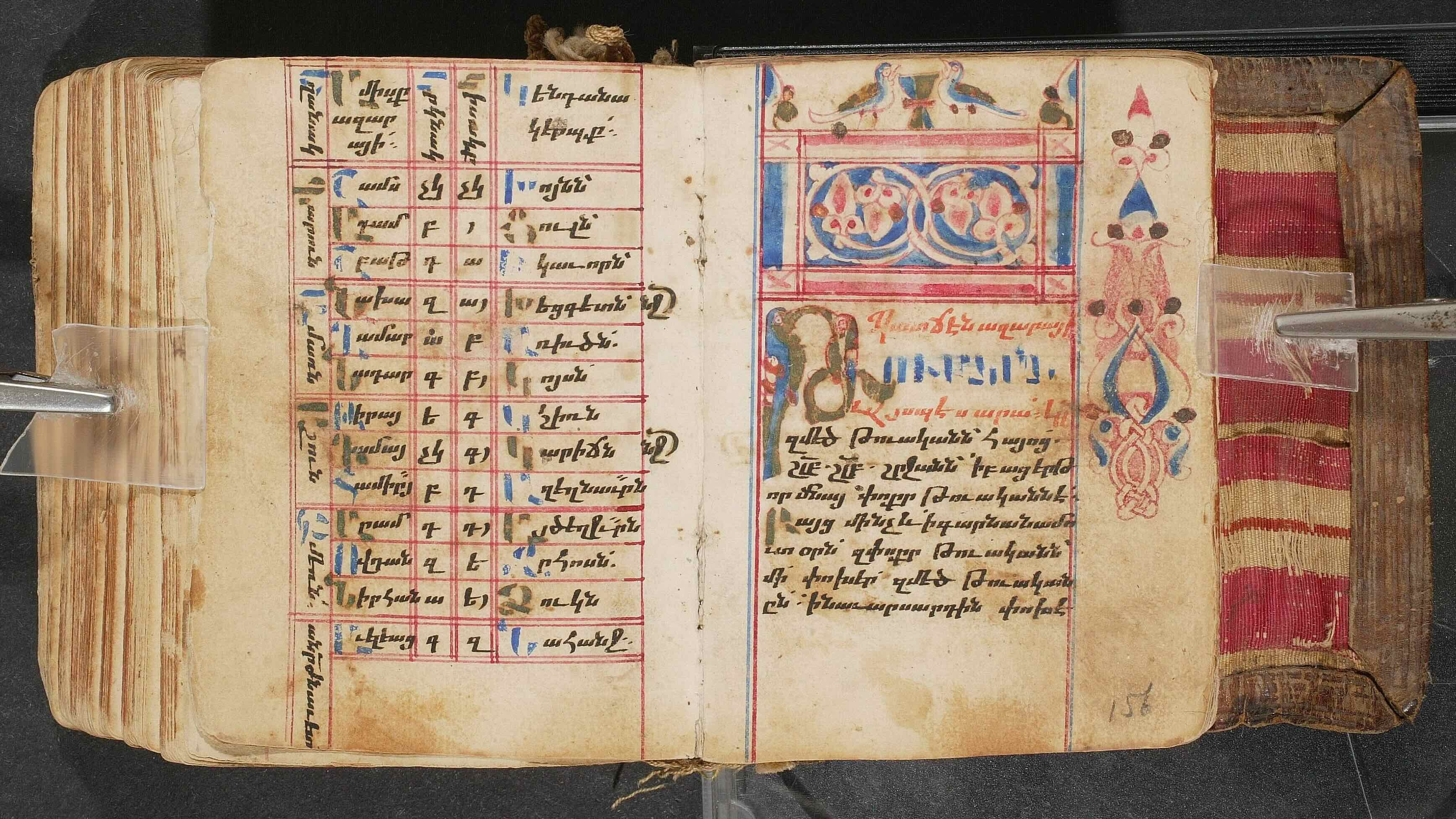

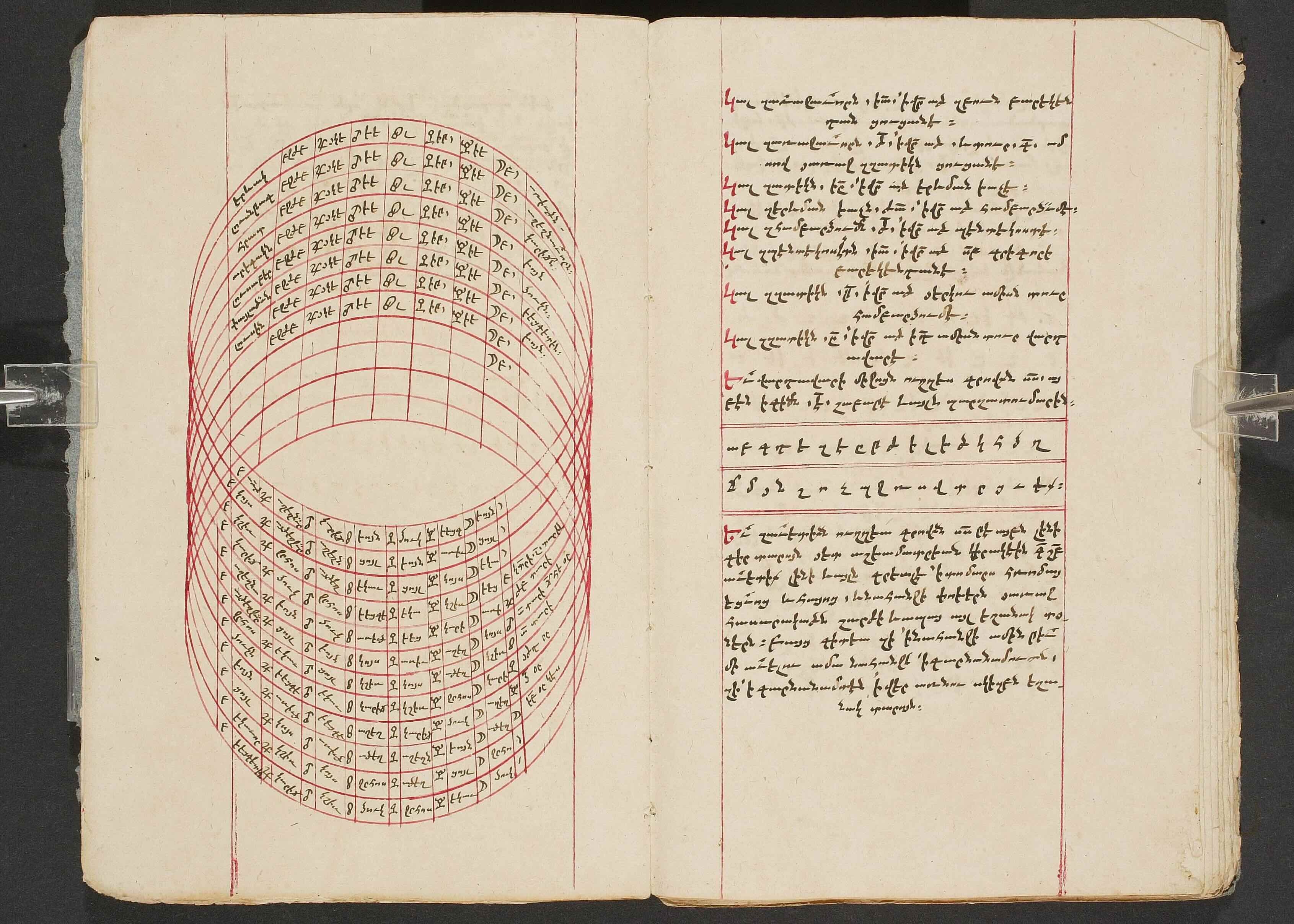

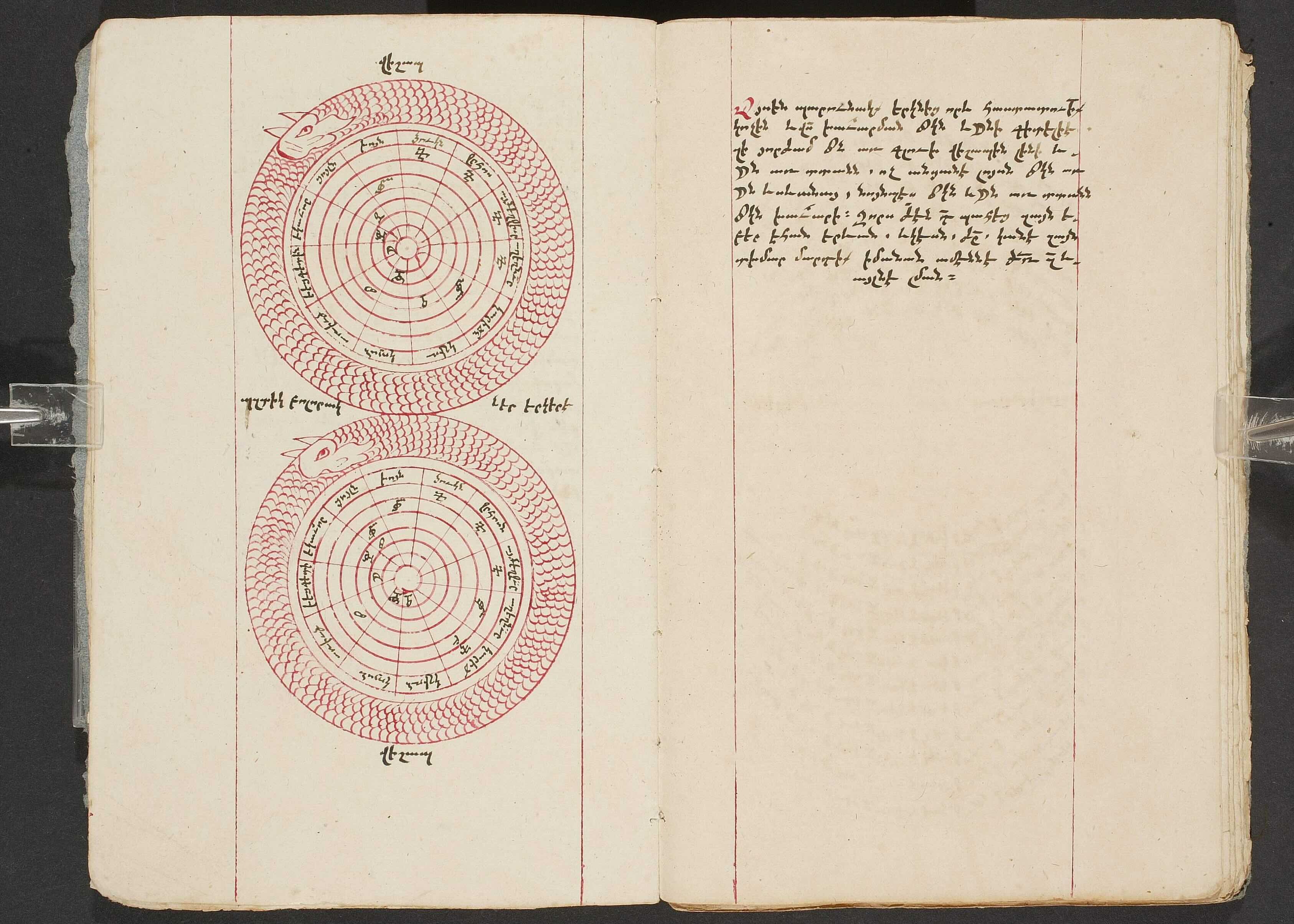

An 18th-century Armenian calendar in tables and charts (parzatōmar). The left side shows symbols and signs of the constellations and the months of the year, and listed on the right side are the Lenten season, Easter, Pentecost, and so on. Collection of Our Lady of Bzummār Convent, Lebanon. (BzAn 00490, fol. 9v–10r)

Armenian vardapets observed how intricately connected the soul of the human person is to something beyond the natural and physical world. These vardapets wove together a natural-spiritual web in the liturgical calendar: a network of the cycles of the day connected to the events of the life of Christ, lives of the saints (speaking to human virtue and way of being), and weekly fast days (challenging the human body towards mindfulness of nutrition and sustenance)—all different stages of activity that bring the human closer to an awareness of their humanity and spark of divinity, while being grounded in the world.

Harmony in Nature Observed Through the Calendar

By observing the harmony of the cyclic flow of nature and combining it with the liturgical calendar, the life of prayer and the spiritual world of human beings was synchronized with the natural world. Over many centuries, there emerged a structure for human life to experience a rich inner and external harmony.

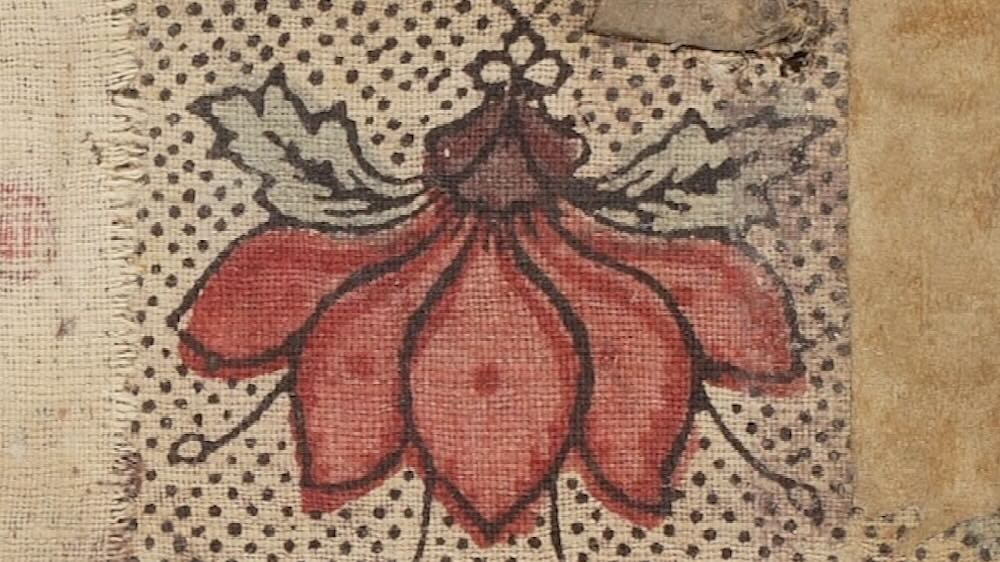

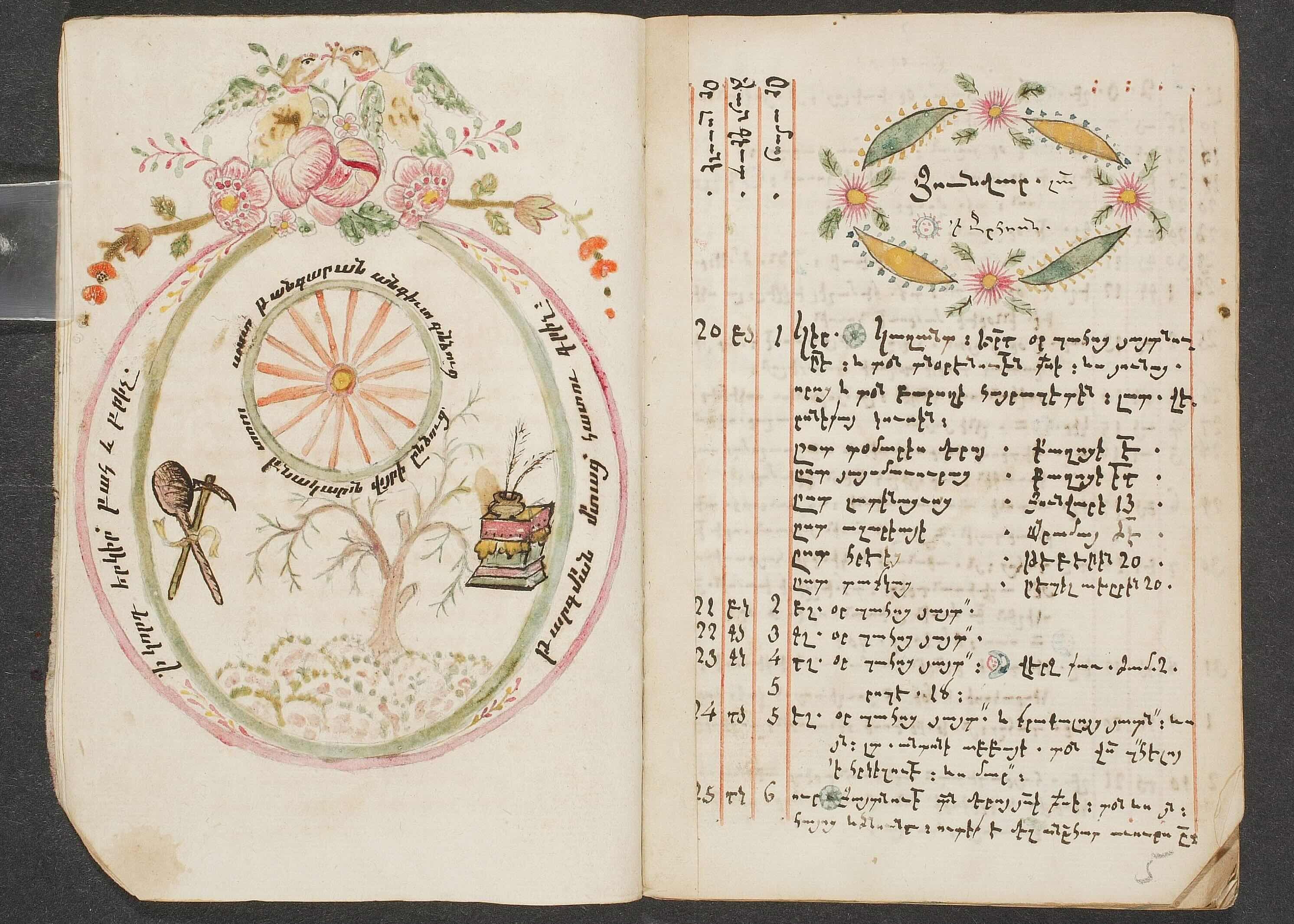

Illustrated and illuminated manuscripts offered an answer to the material and immaterial worlds experienced by human beings, communicated through the cyclical nature of daily, weekly, and yearly calendars that create and shape the time in which human beings exist and flourish.

Daily activates of life are engaged in cycles of repetition. Beyond each day, the connection between nature and human sustenance can be seen in longer-term cycles, such as the names of the months and seasons, shaped around the cycle of agricultural harvest or the blossoming of springtime.

Although we experience cycles of repetitions, no one day is the same; yet its repetitive nature brings forth newness to each experience. A beautiful tapestry emerges out of the cycles of daily light and dark in nature, seasons, and hours, matched with the human experience of day and night where the repetitive cycles of each sphere brings about a unique network of creativity for human activity. And in that process light and life abide.

Further Reading:

Hakob Ghrimets‘i, 1987, Tomaragitakan Ashkhatut‘yunner, H.D. Papazyan (ed.), Academia, Yerevan.

Roberta Ervine, February 29, 2024, “Lecture 4: Armenians and the Psalms,” St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, Armonk, New York.

Roberta Ervine (ed.). 2006. Worship Traditions in Armenia and the Neighboring Christian East, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press.

Christopher Sheklian, June 1, 2020, “Feast and Fast: Further Information on the Armenian Liturgical Calendar.”