Veiled In Ink: Armenian Women In Manuscripts

Veiled in Ink: Armenian Women in Manuscripts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Dr. Ani Shahinian has this story about Women.

When we think of medieval manuscripts in general, we may imagine male monastic scribes in scriptoria with noblemen as their patrons. Yet, in the decorated margins and closing colophons of elegantly-illuminated Armenian Gospels and liturgical books, we discover women’s involvement in the complex process of manuscript production—as commissioners, sponsors, scribes, illuminators, commemorators, intercessors, teachers, and witnesses.

The Armenian manuscript tradition—remarkable for its richness in both text and image—offers a window into the presence of women in medieval intellectual and spiritual life. Spanning centuries, the legacy of Armenian women as patrons, scribes, and witnesses reveals their vital role in preserving and transmitting religious, literary, and cultural heritage.

Colophons as a Window into Women’s Lives

Armenian colophons—ardently-tuned scribal inscriptions, usually at the end of manuscripts—serve as a dedicated space on a folio for the person who copied the manuscript to leave a note of their own. Often, in the colophon a scribe will glorify God upon the completion of the manuscript; situate themselves within their historical and social context; and commemorate their parents, family members, loved ones, and the patrons who commissioned the work—functioning as a form of memorial (յիշատակարան) and personal testimony. In these colophonic writings, women emerge as mothers, patrons, spiritual mothers (for example, nuns who cared for monks), wives, witnesses, offerers of prayers, mourners, and yes, as scribes and illuminators of manuscripts!

Notably, these women are not merely passive figures. Their actions are particularly significant because the commissioning of a manuscript was an expensive, communal act and an expression of piety and power. Women purchased and donated Gospels, sponsored the copying of books, educated young ones, and offered theological reflections wrapped in grief and gratitude. For example: a copy of a Gospel was handwritten in 1465 CE in Archēsh, northeast Lake Van region (modern-day Erciş, Turkey). The book was sponsored by a mother and wife, Khalim-Khat‘un, serving as a powerful elegy for her murdered sons and husband. In this way, the manuscript became a spiritual anchor for her family.

Women Scribes

In addition to recording many of the roles that women employed in the making of Armenian manuscripts, colophons also provide insights into the lives of female scribes.

Throughout the 17th century, several notable women served as scribes—among them Zabel of Cilicia; the nun Hripsime of Halidzor (near the Tat‘ev Monastery); and the virgin Varvar, who in 1655 CE copied a commentary on the Zhamagirk‘ (Book of Hours). Interestingly, “Mariam” was a relatively popular name for female scribes; so far, at least three different Armenian scribes named Mariam have been identified, living between 15th and 18th centuries.

Sometime in the first half to the 15th century, a woman named Mariam, scribe and illuminator (Մարիամ գրչուհին ու մանրանկարչուհին), copied a large volume of the Book of Sermons (Քարոզգիրք) by Grigor Tat‘ewats‘i while in Julfa (modern-day Nakhichevan, Azerbaijan). The colophon, now partially lost, is supplemented by short inscriptions and calligraphic decorations that she left throughout the manuscript, currently held in the collection of the Holy Mother See at Echmiadzin in Vagharshapat, Armenia (Echmiadzin 22).

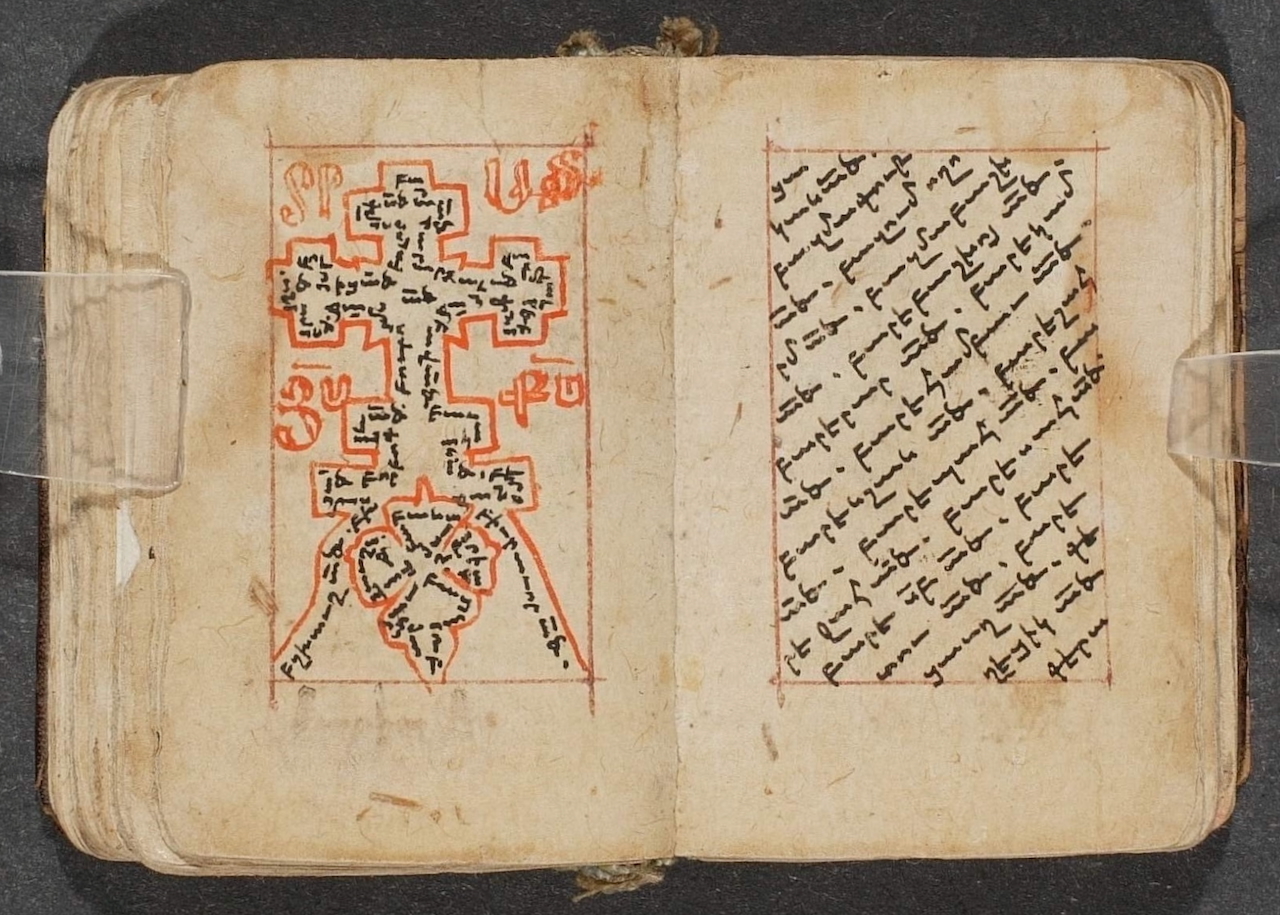

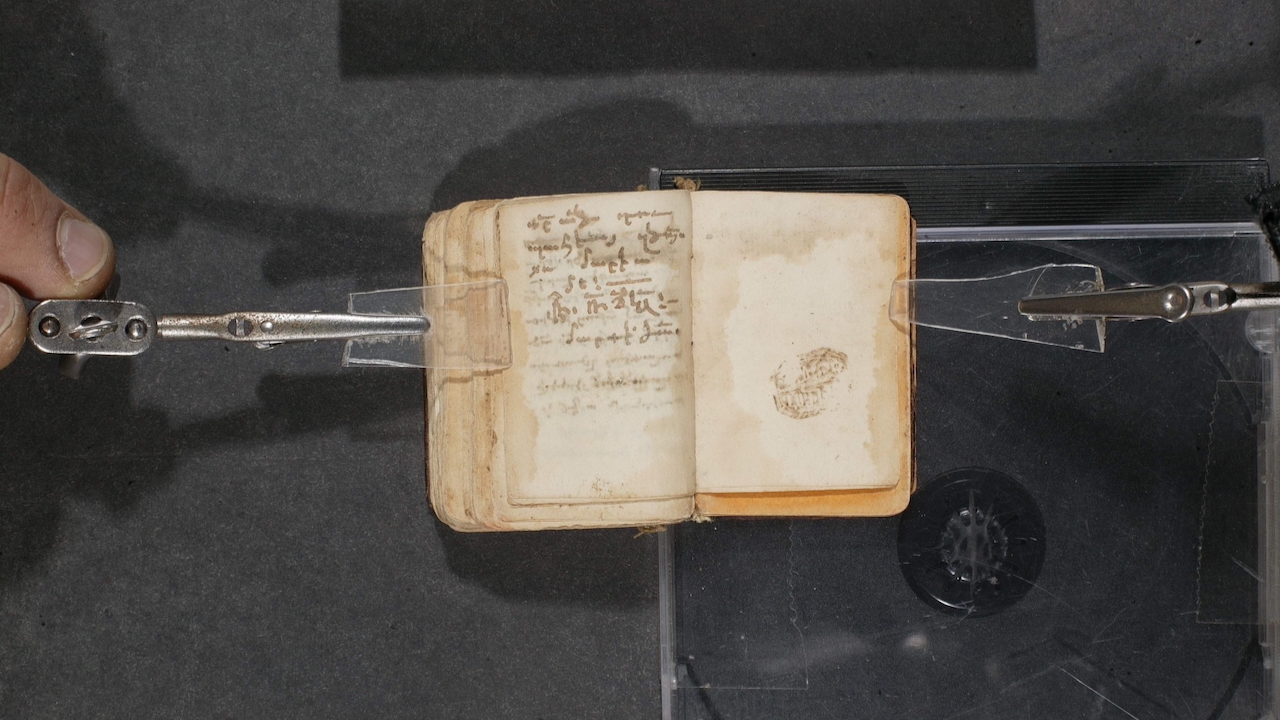

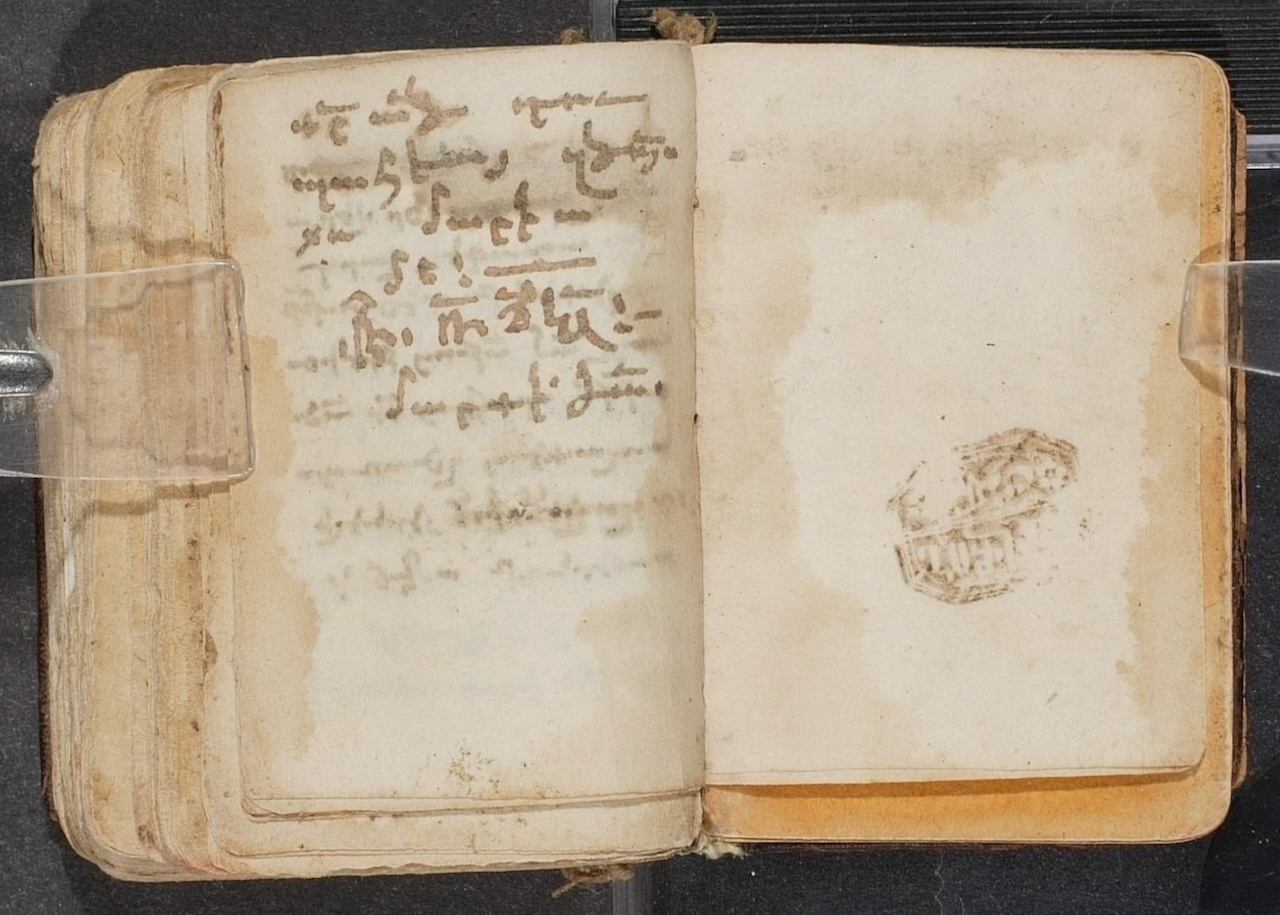

In the early 18th century, another woman named Mariam left her mark in a manuscript now in the collection of Our Lady of Bzummār Convent (Bzummār, Lebanon), digitized by HMML (BzNr 00032). It is hard to know exactly the extent of Mariam’s involvement, but it seems that she edited and added remarks to this pocket-size, illuminated Aghōtʻagirkʻ (Աղօթագիրք), which includes prayers, devotional markings, and readings from the Gospels.

Two folios in the manuscript are a view into the book’s artistry as well as its functionality. The verso of folio 54 features a cross-shaped diagram filled with vertically and diagonally arranged statements of contrition and praises of God. The non-linear, ornamental textuality suggests creative agency, with Տէր Աստուած Յիսուոս Քրիստոս (“Lord God, Jesus Christ”) at the corners outside of the cross in red ink, possibly in Mariam’s hand. The letters form phrases readable along the arms of the cross, emphasizing Christ’s cruciform presence in both text and form.

The recto of folio 55 continues with flowing, densely arranged script in a more conventional rectangular block. As far as is identifiable, the recto script is reflected inside the cross on the verso, bringing a fusion of word and image in a symbolic form embodying a devotional:

«Բազմագութ Աստուած, բազմաողորմ Աստուած, բարերար Աստուած, բարեկամ Աստուած…»

“Compassionate God, merciful God, benefactor God, friend God…”

The manuscript is a well-used, pocket-size prayer book, or Hmayil, containing at least two distinct hands. The first scribe identifies himself as Movsēs. The final scribe, Mariam, writes with a low-quality ink, transcribing a curious and strange compilation of texts assembled as devotional prayers. In several spaces she writes in the name “Yovhannēs,” attributing sections of the manuscript to him, or possibly tracing Yovhannēs’ name which may have faded due to the poor quality of ink and paper. Mariam signs her name in the margins and in the last colophon.

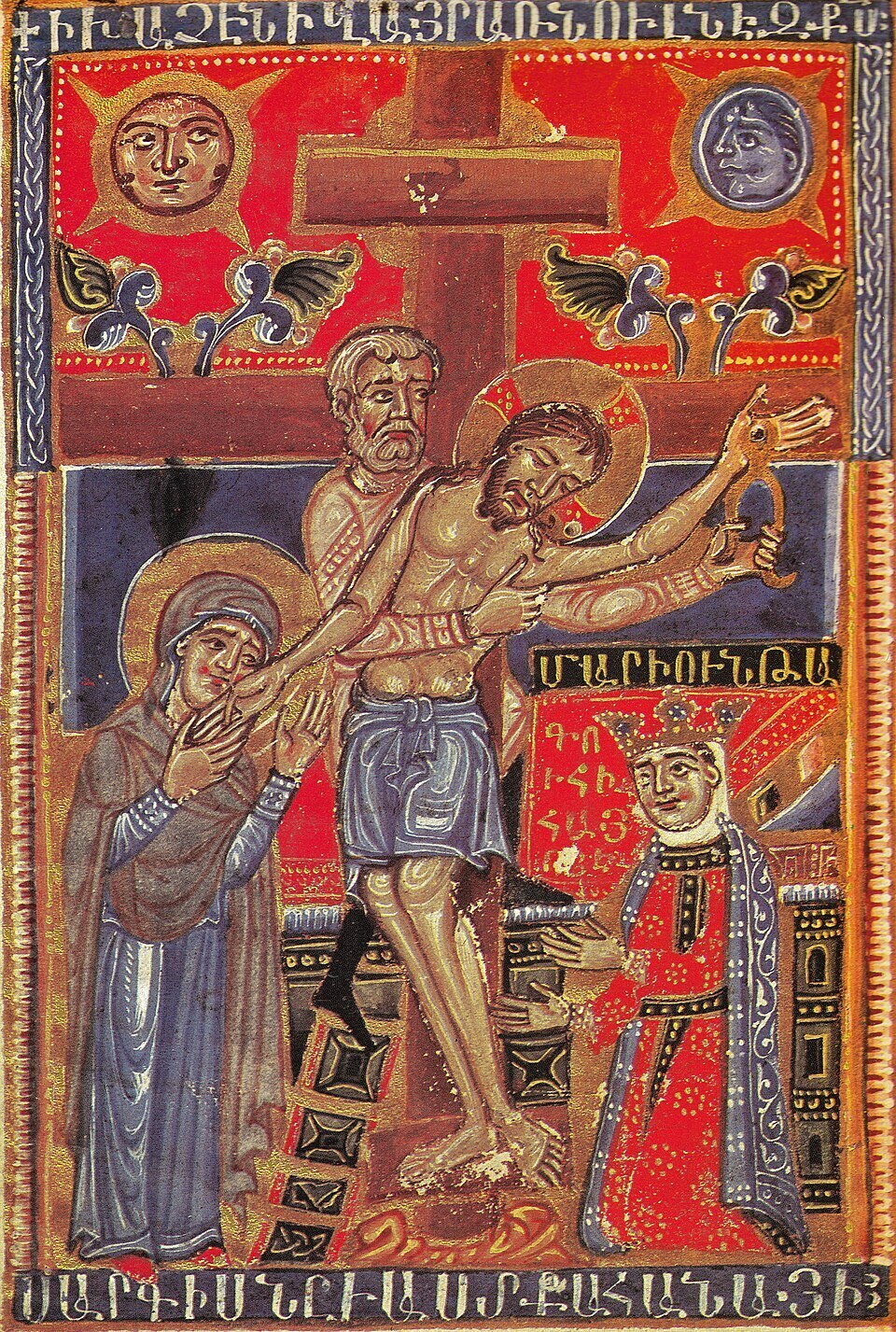

Women Illuminated

Women are also protagonists in the stories preserved in the Armenian manuscripts. Depicted as saints, martyrs, and symbols of spiritual courage, the following illuminations of Armenian women reveal not only theological themes but also distinctive elements of Armenian costume, gesture, and artistic sensibility in their portrayal.

Not only did Armenian women preserve texts—their treasured manuscripts also testify to the lives of women in medieval and early modern Armenia. In their bearing witness, prayers, patronage, and disciplined craftsmanship, they offer their perspective to contemporaries and to later readers. Even though the names of these women are scattered and sometimes hidden on folios, their voice resounds through the ages in their commitment and discipleship. And, in the shimmering gold of a forgotten initial or the quiet ink of a colophon, their devotion still breathes through their words and illuminations.

Further Reading:

Ervine, Roberta 2007. "The Armenian Church's Women Deacons", St. Nersess Theological Review (SNTR) 12: pp. 17-56.

Manoukian, A. (2024). The deaconesses of the Armenian Church. Studia Oecumenica Friburgensia 113. Münster: Aschendorff Verlag.

Meneshian, Knarik. “Women Deacons in the Armenian Apostolic Church Revisited” and “Armenian Women Scribes”: https://

Sarkisian, Matthew & Arlen, Jesse. 2024. An Early-Eighteenth-Century Hmayil (Armenian Prayer Scroll), inSources from the Armenian Christian Tradition: Volume 1. New York: Krikor and Clara Zohrab Information Center.

Zakarian, David. 2023. “Colophons of medieval Armenian manuscripts as sources for women’s history”, in Literary snippets: Colophons across space and time, G. A. Kiraz & S. Schmidtke (Eds.). Gorgias Press. pp. 241-254.