The Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library Is Now Digital

The Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library is Now Digital

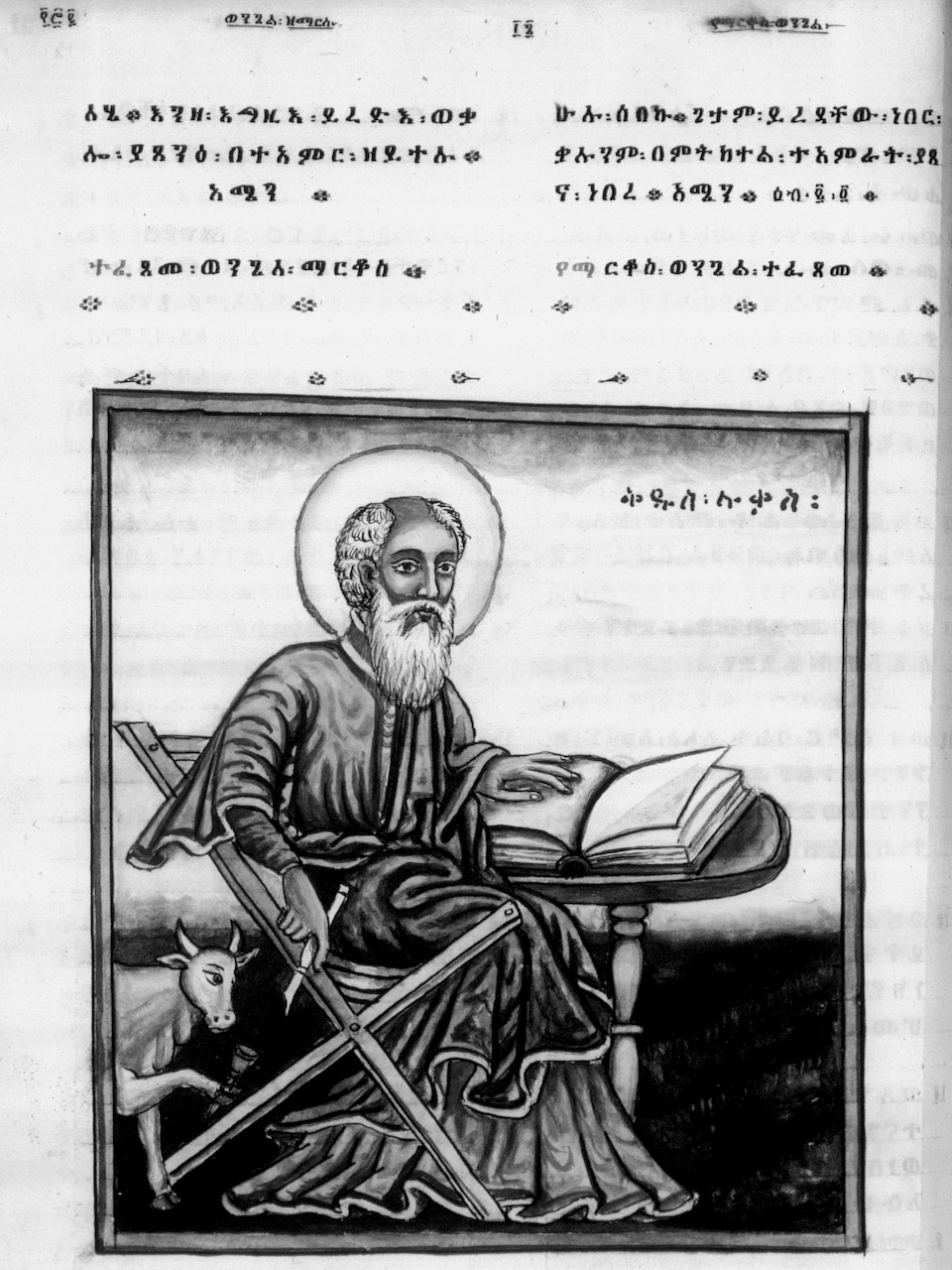

Manuscripts were never meant to be microfilmed.

A scribe carefully copying a text by hand in the 19th century had no idea that technology would soon allow images of books to be created in seconds, reduced in size by a factor of 15 onto transparent photographic film. Nor did they know that this microfilm would allow their books to be easily copied and distributed worldwide.

This conversion technology was the basis for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML) project, a joint effort between HMML, Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Patriarchate. Libraries across Ethiopia were given the opportunity to have their manuscripts photographed onto microfilm for preservation and scholarly access.

Microfilming began in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in late 1973 and continued for 20 years, a tumultuous period that included a Marxist revolution, the arrest and execution of the Ethiopian Orthodox patriarch, famine, and civil war.

Hundreds of libraries had their manuscripts photographed by the EMML team, forming the world’s most important source of texts for scholars of pre-modern Ethiopic culture. Eventually, the photographic project shut down due to an inability to obtain proper microfilming supplies. Completed microfilm reels were given to Ethiopian partners; around 7,500 copies were shipped to HMML for long-term preservation, cataloging, and scholarly access.

Microfilm was never meant to be digitized.

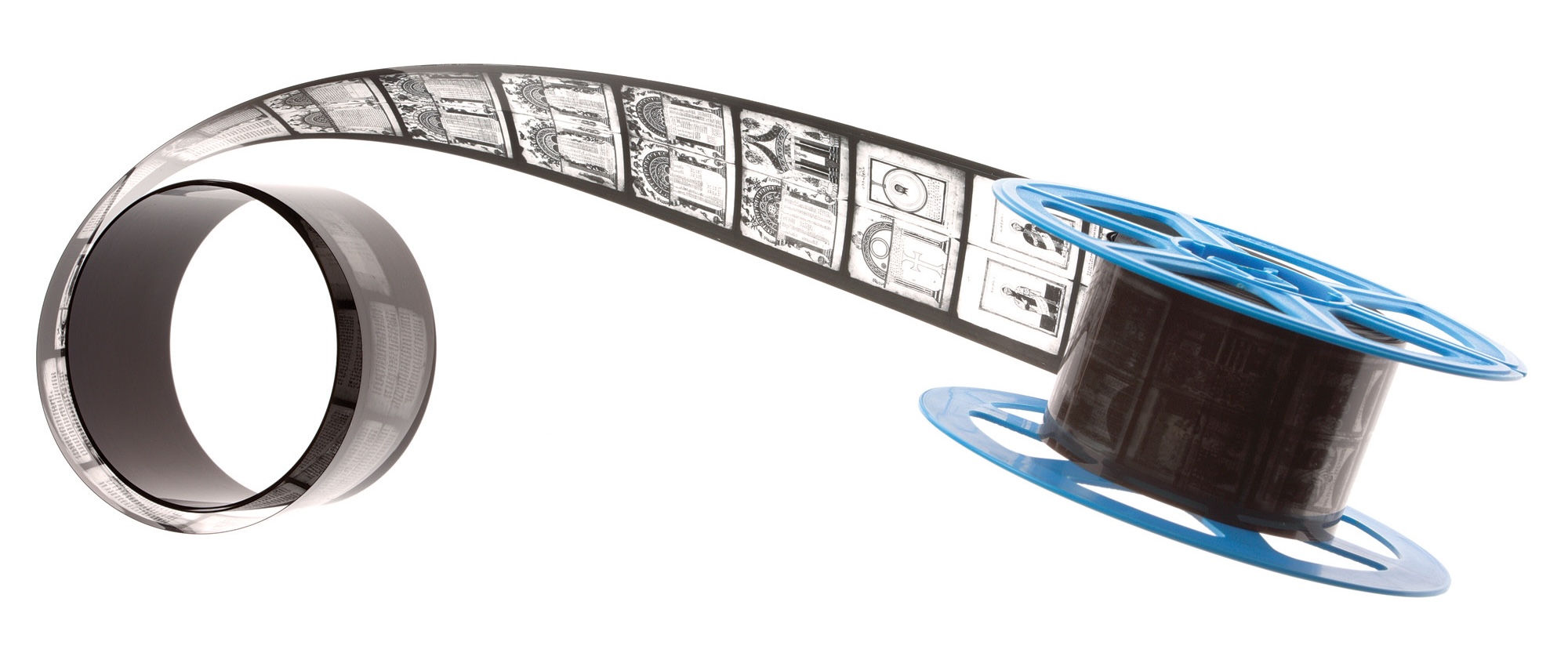

By the 1930s, microfilm technology was in widespread use for archiving such things as newspapers, but the idea of creating electronic copies of the tiny film images was something out of science fiction.

Science fiction became fact in the 21st century, and researchers preferred the ease and access of digital files over analog film. This new process—digital conversion—required specialized scanning equipment.

HMML began scanning (digitizing) its vast collection of microfilm in late 2004. ColorMax, a local digital service provider, funded the purchase of an expensive microfilm scanner through an agreement with HMML to scan a minimum number of microfilms per month. Microfilms requested by scholars were scanned first, with the remainder of the monthly quota made up by what were called “filler” scans. Most of these were EMML microfilms, as HMML already had permission from EMML to scan them. Slowly, HMML’s collection of digitized EMML microfilms grew.

ColorMax purchased a new scanner in 2012 that employed the latest technology. A roll of film passed through the machine in one uninterrupted motion, creating a single long “ribbon” image file containing the contents of the entire film reel. A technician adjusted the cropping, brightness, margins, and alignment of the individual images and then saved all of the image files from the reel at once. It was fast, efficient, and produced microfilm scans of the highest quality. Jeffrey Zumwalde, a technician at ColorMax, became highly skilled in working with this sophisticated scanner to get the finest results possible from HMML’s films.

By mid-2014, ColorMax changed its business focus and Zumwalde had left the company, prompting HMML to purchase its own microfilm scanner. This scanner, although capable of producing images of high quality, scanned one frame at a time—a much slower process. As microfilm digitization started to consume more and more staff time, Zumwalde was offered a part-time scanning job in 2016. He has been with HMML ever since.

Over time, it became known that some EMML partner libraries in Ethiopia were losing access to their microfilm content because their viewing equipment was wearing out. New microfilm readers were expensive and hard to get, and many scholars couldn’t afford to pay for multiple films to be scanned. The original manuscripts, located throughout the country, were generally unobtainable for research.

HMML decided to put the 1,500 scanned EMML films into HMML Reading Room for free online access. This helped, but it still left a mountain of EMML films that needed digitization.

In 2021, a generous donation from Robert Weyerhaeuser made it possible for HMML to obtain a microfilm scanning system using the same “ribbon image” technology that Zumwalde had mastered at ColorMax. HMML prioritized the high-volume scanning of EMML microfilm; in a four-year period, Zumwalde digitized the remaining 6,000 EMML films, four times what was scanned in the previous 16 years.

All of HMML’s EMML manuscripts are now online in HMML Reading Room after this 20-year analog-to-digital conversion project, which took as long as the original microfilming in Ethiopia. Cataloging of the collection is ongoing and recently reached the milestone of making descriptions available online for 4,000 EMML manuscripts.

Digital images were never meant to be…?

What will the next conversion of this information look like? We won’t know until that new technology develops, but it’s certain that the treasury of Ethiopian culture contained in the EMML collection has not ended its journey.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Winter 2025 issue of HMML Magazine.