The Case Of The Mysterious Pie And The Amsterdam Theater

The Case of the Mysterious Pie and the Amsterdam Theater

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Art & Photographs collection, Dr. Catherine Walsh shares a story about Food.

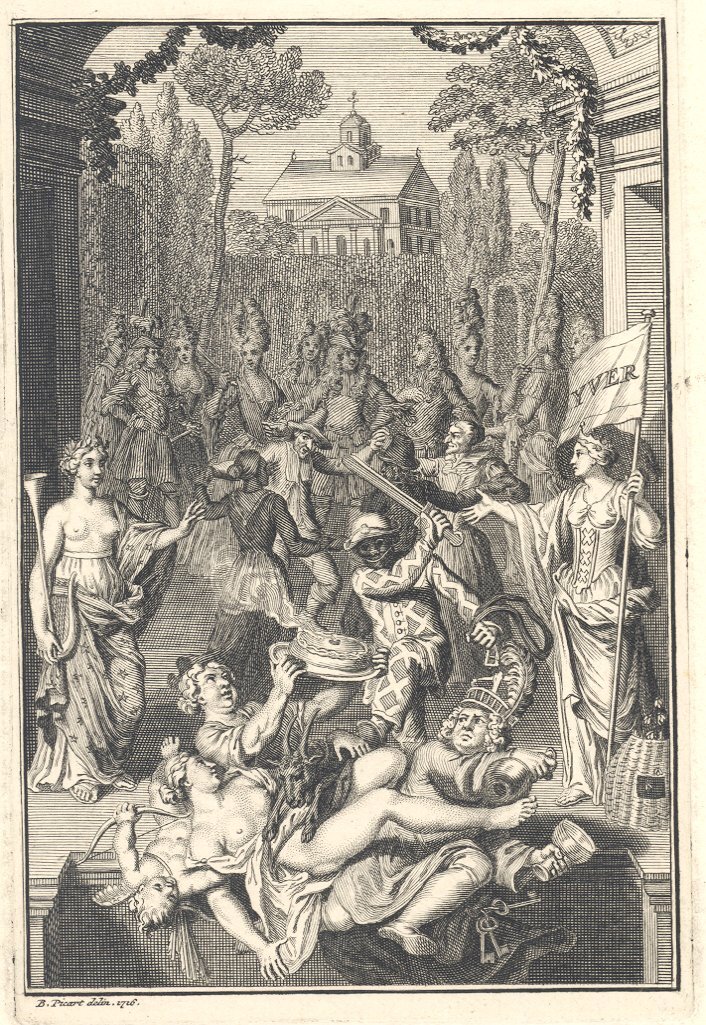

Pie. Today, for many, this tasty baked good with its short, flaky crust suggests associations of home-cooked meals and simple, traditional cuisine. However, this has not always been the case. Food is deeply embedded with cultural meaning, and in Allegory of Amsterdam (AAP2154)—a Dutch print created in 1716 by a French engraver living in Amsterdam, Bernard Picart—a centrally positioned pie tells a very different story.

Picart sets the scene on the anatomy of a stage, framed by the proscenium arch. Seated in the foreground on the edge of the stage, his legs dangling over the pit and hands clutching a goblet and a bottle of wine, is Joan Pluimer, the director of the Amsterdamse Schouwburg. Two women are also arrayed in the foreground, allegorical figures who may represent lust and gluttony, the latter holding up a steaming raised pie on a platter. Above, the figure of Harlequin, garbed in his traditional checkered costume, raises a sword threateningly as he gazes on the scene below. He is flanked on either side by Thalia (the muse of comedy and idyllic poetry, on the left) and an allegory of Amsterdam (on the right). This personification of the city of Amsterdam stands near a beehive (emblematic of the theater) and holds a banner bearing the word “Yver,” part of the phrase “By Yver in love bloeyende,” the motto of the chamber of rhetoric (drama society) in Amsterdam. Behind them, actors dance and converse.

First appearing in a satirical pamphlet, this allegorical print also served as the frontispiece of a book published in 1719, De dichtkunst én de schouwburg, sponsored by the artistic society Nil Volentibus Arduum (NVA, translated as “Nothing is arduous for the willing”).

NVA was composed of playwrights and by this point led by Ysbrand Vincent, Picart’s father-in-law. The society set for itself the goal of uplifting the Dutch theater by writing, translating, and adapting plays, especially French works. This focus caused uproar among people who were quite happy with the theater as it already stood, as well as those who disapproved of the controversially “immoral” theater altogether. The rift led to the so-called “Battle of the Poets” in Amsterdam in the early 18th century.

So, if the goal of the engraving is to criticize the current state of the Dutch theater, where does the pie come into the story? Why is it placed so prominently at the center of the composition, the focus of attention for Pluimer’s disgust and Harlequin’s violence?

Luxury and Spectacle

First, note that such pies were very different in the Dutch Republic, a foodstuff with a complicated history. The image depicts a raised pie, an item that had historically served less as food than as spectacle. Standing pies might serve as centerpieces at entertainments, built to resemble objects or to contain whole animals.

The crusts themselves were made of coarse flour and hot water, designed to be molded and producing a hard, sturdy shell that was generally not meant to be eaten. Typically, the filling was meat-based even if sweet—producing a “pastey” (savory) as opposed to a “taert” (sweet)—and, if it was eaten at all, the filling might be ladled out and the crust tossed away. Perhaps this is the origin of the Dutch saying (translated), “For the lack of bread, you eat the crust of raised pies,” meaning you do what’s necessary, even if it’s not desirable.

Interestingly, Picart’s 1716 print is a redesign of a 1685 print by Romeyn de Hooghe, Spotprent op de Schouwburgstrijd, which Picart also copied directly. This original version included a centrally placed pie, but sculpted into an elaborate pastry deer. This spectacular pie, reminiscent of medieval feasts, was replaced in Picart’s 1716 print with a simpler, and perhaps more familiar, raised pie.

Raised pies also made for elaborate visual displays in Dutch still lifes, such as Pieter Claesz’s Still Life with a Turkey Pie. Two pies are featured: one still uncut and surmounted by a full turkey, complete with feathers and clearly representing the pie as spectacle, and the other broken open and spilling forth onto the plate. Of course, like so many of the rich layers of meaning inherent in emblematic Dutch paintings, a pie was never just a pie. A tension existed in art and literature, as described so memorably by the scholar Simon Schama as a balance between gluttony and nourishment, abundance and immoderation.

Elaborate displays of food (overvloed) might serve simultaneously as praise for the Dutch wealth—associated with hard work, international trade, and a booming merchant class—and also as a Protestant warning of the dangers of moral decay, vanity, and excess. Is the burst-open pie a delectable food to be enjoyed, or is it rotting before our very eyes?

Edible Ethics

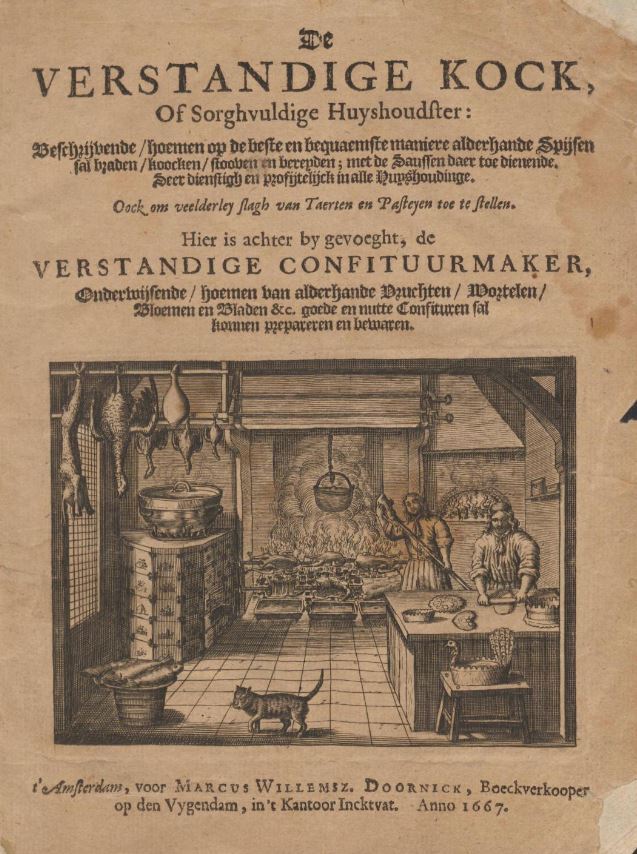

A famous Dutch cookbook, De verstandige kock, of Sorghvuldige huyshoudster (The sensible cook, or careful housekeeper), originally published in 1667 and probably intended for middle and upper classes, includes many recipes for pies. Here, at least, meals were designed to be produced and consumed as food, not mere spectacle. One recipe for a spring chicken pastey reads:

Take the spring chicken boiled a little while, place it in the pastey, spice it with cinnamon, cloves, a little nutmeg, and ginger, place with it Damson prunes, candied pears and cherries, citron, pine nuts, and butter; let it bake for an hour. The sauce should be made with wine and sugar.

With exotic spices from the East, sugar likely originating in the Caribbean, citrus and fruits and wine, this recipe was only possible in a society that took for granted the benefits of global trade and a constantly replenished market for goods. Some moralizers lamented exotic spices like cinnamon that lured eaters away from what they considered simple, wholesome home cooking; sauces that disguised meat and vegetables; and the moral menace of sugar, the supreme sign of decadence.

Viewed in this way, pie becomes a pretext for moralizing. It is gluttony and luxury wrapped up in a pastry case, with decadent spices and exotic candied fruits hidden inside: a temptation that once opened, might lead to decay.

Returning to Picart’s engraving, we might then view the pie at the center of the print in a different fashion. In this interpretation, it might be seen as a representation of the luxury and overvloed that had set the theater on the wrong path, detouring from the French classicism and critical thought preferred by NVA.

But don’t let that stop you from trying out the pie recipe!

Further Reading:

Barnes, Donna R., and Peter G. Rose, Matters of Taste: Food and Drink in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and Life. Syracuse University Press, 2002.

De dichtkunst én de schouwburg: voorspél, met muzyk én danssen. Amsterdam: Hendrik Bosch, 1719.

De verstandige kock, of Sorghvuldige huyshoudster. Amsterdam: Marcus Willemsz. Doornick, 1667. [Full text available online at Delpher]

Leemans, Inger. “Bernard Picart’s Dutch Connections: Family Trouble, the Amsterdam Theater, and the Business of Engraving.” In Bernard Picart and the First Global Vision of Religion, ed. Lynn Hunt, Margaret C. Jacob, and W. W. Mijnhardt, 35-58. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2010.

“Pie.” In Encyclopedia of Food and Culture, ed. Soloman H. Katz and William Woys Weaver. New York: Scribner, 2003.

Riley, Gillian. “‘Eat Your Words!’ Seventeenth-Century Edible Letterforms,” Gastronomica 1, no. 1 (2001): 45-59.

Schama, Simon. The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. New York: Vintage Books, 1987.