Protecting Travelers And Maritime Contacts In The Eighteenth Century Mediterranean

Protecting Travelers and Maritime Contacts in the Eighteenth-Century Mediterranean

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Malta collection, Dr. Daniel K. Gullo shares a story about Travel.

The great Age of Sail conjures in our minds vast stretches of ocean populated by solitary vessels engaged in lonely journeys across the expanse of the deep blue under the spread of canvas. The seaway, like our highways and roads, was, however, a populated place frequented by ships sailing common routes, often in convoy, and frequently in communication with one another.

In the early eighteenth century, Aragonese, Catalan, and Castilian merchants traded frequently with Maltese merchants along established routes, while the Spanish navy patrolled North Africa and defended established presidios (garrisoned outposts) on the coast to ward off Barbary pirates. The Spanish navy worked with other maritime allies, such as the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Their fleets often sailed together to protect European merchants and travelers from Ottoman and North African piratical activity.

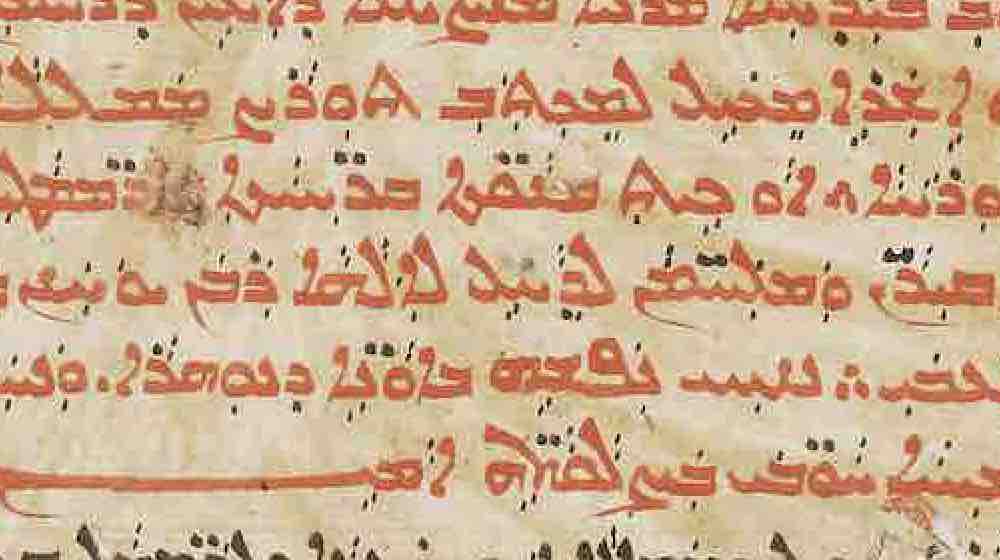

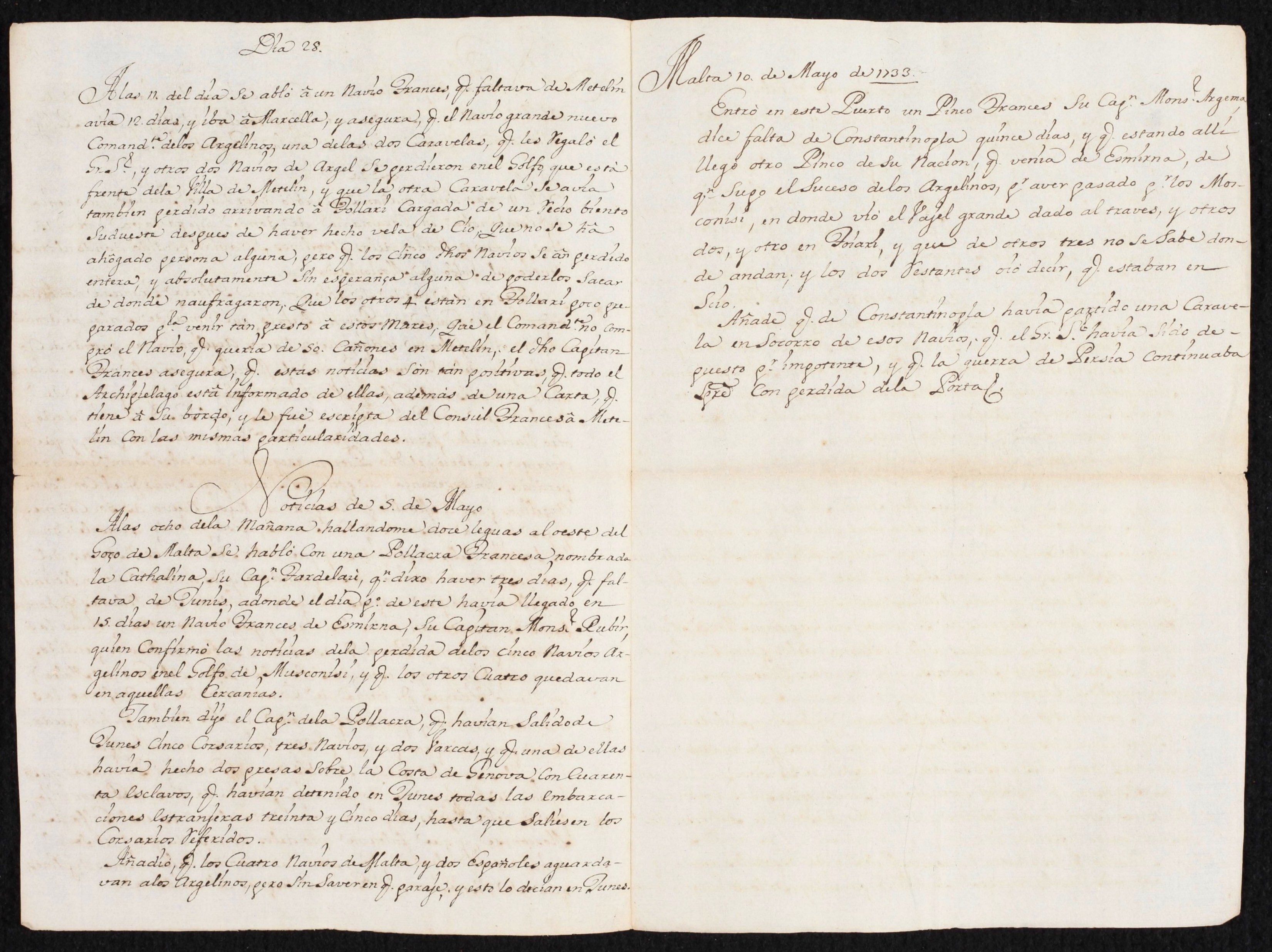

An example of the populated sea and the types of contact between ships can be seen in a short dispatch preserved in the Malta Study Center Collection at HMML. The dispatch (HMML 00247) contains a description of the naval actions and ship contacts of the Spanish royal squadron commanded by Blas de Lezo y Olavarrieta (1689–1741), which patrolled with a squadron of the Order of Saint John off the coast of Tunisia in April and May 1733.

The Spanish and Maltese patrol was a continuation of the military operations against Abu l-Hasan Ali I (1658–1756), Bey of Tunisia, which began with King Felipe V's (1683–1746) capture of the towns of Oran and Mers el-Kebir in July 1732. Rumors began to circulate that the Bey of Tunisia had asked the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud I (1696–1754) to send a naval force to reclaim the Algerian ports from the Spanish. Felipe V, fearing Ottoman intervention, ordered his Mediterranean squadron with the support of the Knights of Saint John to intercept any relief force sent from Turkey to assist the Tunisian Bey.

Similar to questioning travelers at an inn on a road, captains would hail friendly ships for news. HMML 00247 records contacts between the Maltese and Spanish squadron and French merchant ships while the patrol sailed between Pantelleria, Malta, and Tunisia from April 27 to May 10, 1733. The text shows Blas de Lezo's eagerness to know about the rumored Turkish and Algerian squadrons, and especially the rumors that the Bey had lost several ships in a storm off the coast of Mostagnem, Algeria. Hailing a merchant flying a French flag on April 28, the captain en route to Marseilles told Blas de Lezo to rejoice in the news about the sinking of the Ottoman ships, news now commonly known throughout the entire archipelago. One week later, however, another French merchant contacted off Gozo reported that only five of the Ottoman ships had been damaged, while another four continued to patrol the area in search of prizes.

Blas de Lezo sought additional news when he arrived at the Great Harbor in Valletta. Malta’s harbors were neutral, and the Order of Saint John took great pains to make sure that European powers such as France, Spain, and Italian States recognized this neutrality and respected their laws. Captain de Lezo’s arrival at Valletta was indeed understood as an arrival at a safe harbor. His own government had published a notice in Madrid (HMML 00230) supporting Malta’s neutrality, recently negotiated between Fra’ Pedro Dávila de Guzmán (1668–1738), ambassador of the Order of Saint John to Spain, and King Felipe V.

This neutrality was extended to other countries, such as France, and for this reason, on May 10, 1733, Blas de Lezo was able to come in contact with a recently arrived French merchant from Constantinople while their ships harbored in Valletta. The merchant informed Captain de Lezo that the sultan was preparing additional ships to support efforts in Algeria against the Spanish. This new Turkish fleet, however, failed to materialize, and both the Spanish and Maltese squadrons returned to their respective harbors of Cadiz and Valletta after 50 days at sea.

Battle Afoot

A few years later, the Order of Saint John’s squadrons traveled west to Spain to patrol the coast against Barbary pirates, as a continuation of the earlier conflict with Algeria. Their encounters are described in the Portuguese pamphlet Relaçao do encontrado havido no dia 6 de Novembro de 1736, printed by Teotónio Antunes Lima in Lisbon in 1736 (HMML 00531). The document is a dramatic testament to the naval encounters between hostile maritime powers at sea.

The pamphlet recounts a famous naval battle off Marbella from November 6 to 8, 1736, between three Algerian corsairs and three frigates (vascelli) of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem: the Sant' Antonio, San Giovanni, and San Vincenzo Ferreri. The Order’s squadron was commanded by Lieutenant General Fra’ Bartolomeo Tomassi (1668–1768) on the frigate Sant' Antonio. The outcome of the battle included the capture of the 36-gun Algerian frigate, Demi Lune, captained by Sulloqui Mahmet Schiulah, and the 34-gun Algerian frigate l'Arangy, captained by Hagi Solimani, a renegade of Pantelleria. The action was so renowned that António Caetano Luís de Sousa, the 4th Mârques de Minas and 6th Conde de Prado, provided funds to print the pamphlet in Lisbon (as seen in his coat of arms on the title page), in part to recognize his relative, Fra' Sousa, who served as secondo capitano on the frigate San Giovanni.

Witnesses to these encounters at sea can be found in paintings and watercolors that visualize these events, often created from the written notices that spread across Europe in dispatches and pamphlets. Famous naval actions, like those in Marbella, were commissioned in oil and watercolor, as seen in a late eighteenth-century collection of watercolors preserved in HMML’s Malta Study Center Collection.

This watercolor was likely commissioned by a French knight of the Order of Saint John during a visit to Malta. The portfolio of collected maritime art, which includes the Marbella naval action, is a record of the Order’s mission to defend the seas. At the same time, it became a memento from Malta, acquired during travels to the Order’s central convent. Whether as dispatches, pamphlets, or artwork, these records of the naval actions of the Spanish and the Order of Saint John popularized the continuing need to protect travelers across the sea, as the Mediterranean was ever populated with friend and foe, both under sail and above the sirens of the deep.